Seeing a Myth March 2, 2014 Mary R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order of Worship Transfiguration Sunday, February 14, 2021

Order of Worship Transfiguration Sunday, February 14, 2021 WELCOME Hello God, thank you for this day. It’s 9:03 and we need your help. Guide us by your Holy Spirit to reach new people, Connect us all through Christ’s love, and Empower us to love and serve others. Amen. PRELUDE Deo Gracias P. Cattaneo CALL TO WORSHIP Psalm 50:1-6 UMH 783 HYMN 2103 We Have Come at Christ’s Own Bidding HYFRYDOL SCRIPTURE 2 Corinthians 4:3-6 PASTORAL PRAYER AND LORD’S PRAYER Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen. HYMN 173 Christ, Whose Glory Fills the Skies RATISBON SCRIPTURE Mark 9:2-9 MESSAGE Rev. Rebecca Voss GENEROSITY, INVITATIONS and CELEBRATIONS HYMN 2102 Swiftly Pass the Clouds of Gory NETTLETON BENEDICTION POSTLUDE Voluntary #1 J. Beckwith PRAYER CORNER We lift up Andrea Anderson who is staying at Aspirus Hospital while being diagnosed and treated for severe hip and pelvic pain and weakness. Lord, give her comfort and hope as you give her medical team knowledge and wisdom to best care for her. Called to Glory __ _ _ Pastor Rebecca Voss As a child growing up near Madison, I remember looking forward to our trips up to Athens to visit my dad’s side of the family. -

Matthew's Gospel

MATTHEW’S GOSPEL by Daniel J. Lewis © copyright 2008 by Diakonos, Inc. Troy, Michigan United States of America 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Who was Matthew? .................................................................................................................................... 5 How, When and Where was the 1st Gospel Composed?............................................................................. 6 Structure ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Central Theological Motifs......................................................................................................................... 9 The Text of Matthew ................................................................................................................................ 11 The Birth Narratives (1-2) ............................................................................................................................ 11 The Genealogy of Jesus (1:1-17).............................................................................................................. 11 The Virginal Conception of Jesus (Mt. 1:18-25)...................................................................................... 13 The Visit of the Magi (Mt. 2:1-12).......................................................................................................... -

BLE 2022 (Pdf)

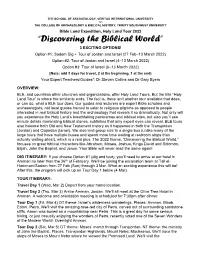

THE SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY, VERITAS INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY AND THE COLLEGE OF ARCHAEOLOGY & BIBLICAL HISTORY, TRINITY SOUTHWEST UNIVERSITY Bible Land Expedition, Holy Land Tour 2022 “Discovering the Biblical World” 3 EXCITING OPTIONS! Option #1: Sodom Dig + Tour of Jordan and Israel (27 Feb–13 March 2022) Option #2: Tour of Jordan and Israel (4–13 March 2022) Option #3: Tour of Israel (6–13 March 2022) [Note: add 3 days for travel, 2 at the beginning, 1 at the end) Your Expert Teachers/Guides*: Dr Steven Collins and Dr Gary Byers OVERVIEW: BLE, and countless other churches and organizations, offer Holy Land Tours. But the title “Holy Land Tour” is where the similarity ends. The fact is, there isn’t another tour available that does, or can do, what a BLE tour does. Our guides and lecturers are expert Bible scholars and archaeologists, not local guides trained to cater to religious pilgrims as opposed to people interested in real biblical history and the archaeology that reveals it so dramatically. Not only will you experience the Holy Land’s breathtaking panoramas and biblical sites, but also you’ll see minute details illuminating biblical stories, subtleties that only expert eyes can reveal. BLE tours also balance both Old and New Testament history as it happened in both the Transjordan (Jordan) and Cisjordan (Israel). We also limit group size to a single bus (unlike many of the large tours that have multiple buses and spend more time waiting at restroom stops than actually visiting sites!), which is a real plus. The 2022 theme, “Discovering the Biblical World,” focuses on great biblical characters like Abraham, Moses, Joshua, Kings David and Solomon, Elijah, John the Baptist, and Jesus. -

Biblical Illustrator Articles for the GOSPEL PROJECT (Date of First Use: Summer 2020)

Biblical Illustrator Articles for THE GOSPEL PROJECT (Date of first use: Summer 2020) Unit 1 – Jesus the Healer Session 8 – July 26 • Solomon in All His Splendor Session 1 – June 7 • Birds in Israel • InSites: Miracles of Christ • First-Century Agricultural Practices • Who Were the Samaritans? • Galilee in Jesus’ Day Session 9 – August 2 • Samaria • QuickBites: Sheep: Their Cultural Importance • Abundantly: The Meaning Session 2 – June 14 • Thieves and Robbers • Saved: A Word Study • Sheepfolds: Their Construction and Use • Death, A First-Century Understanding • Jesus' Use of Allegory • Fear in Mark’s Gospel • Asleep or Dead? Unit 3 – Jesus the Miracle Worker Session 3 – June 21 • At the Pool of Bethesda Session 10 – August 9 • Jesus, the Paralytic, and the Sabbath • Demon Possession: A First-Century Understanding • The Pools of Bethesda • Gadara, Gerasa, or Gergesa? • Jesus' Use of Miracles • Demons: A First-Century Understanding • Legion Session 4 – June 28 • Jesus, the Pharisees, and the Sabbath Session 11 – August 16 • Messianic Miracles: First-Century Jewish • Bread and Bread Making in the Ancient World Expectations • “Signs” in the Gospel of John • “Signs” in the Gospel of John • Beside the Sea of Galilee • The Pool of Siloam Session 12 – August 23 • Storms on the Sea of Galilee Unit 2 – Jesus the Teacher • Simon Peter: The Man and His Ministry • Wind, Weather, and the Sea of Galilee Session 5 – July 5 • Early Ships and Boats • Salt in the Ancient World • The Sermon on the Mount: An Overview Session 13 – August 30 • Lamps in Ancient Israel • Jesus’ Inner Circle • Simon Peter: Eyewitness to the Majesty Session 6 – July 12 • The Mount of Transfiguration • Jesus on Discipleship • Animal Imagery in the New Testament • Luke's Use of ''Kingdom'' • Disciple Session 7 – July 19 • "Our Daily Bread" • The Churches’ Use of the Lord’s Prayer • Widowhood in Jesus’ Day • “Our Father”—Jesus’ Prayer Practices and Instructions Titles in Red are current issue articles. -

Download Full Itinerary

Join La Sierra University Church and La Sierra University Alumni Association for their Centennial Tour to the Land of the Bible—March 17–April 10, 2022 Walk and Live the Story 10 Amazing Days exploring the Life of Christ in Israel 4 Amazing Days exploring Biblical History in Jordan 11 Amazing Days exploring Early Biblical and Egyptian History in Egypt with Senior Pastor Chris Oberg, La Sierra University Church Archaeologists Dr. Larry Geraty and Dr. Kent Bramlett La Sierra University Israel, Jordan, Egypt—March 17-April 10, 2022 Israel & Jordan—March 17-30, 2022 Israel Only—March 17-27, 2022 Jordan & Egypt—March 26-April 10, 2022 Egypt Only—Excludes Sinai—March 31-April 10, 2022 Egypt Only—Includes Sinai Arrive Aqaba, Jordan March 30, 2022 (by noon—extremely important to meet group to board ferry) Land flowing with milk and honey. Promised land. Holy land, Canaan land. The land, Joshua, Moses’ successor as leader of Israel, was poised at the River Jordan to enter and take possession of Canaan, an unremarkable stretch of territory sandwiched between massive and already ancient civilizations. It would have been unimaginable to anyone at the time that anything of significance could take place on that land. This narrow patch had never been significant economically or culturally, but only as a land bridge between the two great cultures and economics of Egypt and Mesopotamia. But it was about to become important in the religious consciousness of humankind. In significant ways, this land would come to dwarf everything that had gone before and around it. (The Message, Eugene H. -

Study 08-06-20.Docx

THE UNCREATED LIGHT THE SERVANTS AND THE MASTER August 6, 2020 The Transfiguration – August 6th Revision C GOSPEL: Matthew 17:1-9 EPISTLE: 2 Peter 1:10-19 In the West, Transfiguration Sunday is celebrated just before Lent rather than in August as is the custom of the Orthodox Church. The Gospel and Epistle readings are identical in the Western lectionaries, except that only verses 16-21 are used from 2 Peter. In the Orthodox lectionary, the account of the transfiguration from Luke 9:28-36 is also read at Matins. Table of Contents Gospel: Matthew 16:28-17:9, Mark 9:2-13, Luke 9:28-36 ....................................................................................... 629 The Light of God ................................................................................................................................................. 629 The Servants and the Master ................................................................................................................................ 631 Moses and Elijah on Sinai .................................................................................................................................... 632 Constructing Tabernacles ..................................................................................................................................... 635 The Father Speaks ................................................................................................................................................ 637 The Transfiguration Prefigures Tabernacles ....................................................................................................... -

Mark Chapter 9 – the Transfiguration (Part 1)

mark h lane www.biblenumbersforlife.com MARK CHAPTER 9 – THE TRANSFIGURATION (PART 1) SUMMARY Of all the miracles and events surrounding the life of Jesus – the Transfiguration is the most other-worldly. When Jesus healed, people saw a human transform from sickness to health in a short time. When Jesus healed it was possible to comprehend – like a normal healing – just speeded up. None of us living today have ever experienced seeing someone ‘transfigure’. It is outside our earthly frame of reference. The number 9 means ‘Judgment’ or ‘Spirit’. In Mark chapter 9 presents us with a lesson concerning spiritual realities beyond our comprehension. This is a clue the message concerns other-worldly affairs. Similar to the rest of our papers on Mark , Chapter 9 is highly prophetic. According to our interpretation: Mark 6 – Birth of the Church – Large Number of Jews Believe – Hungry for Truth Mark 8 – Decline of the Church – Large Numbers of Christian Believers – Starving for Truth Mark 9 – Death of the Church – The Great Apostasy and Martyrdoms - Just Before the Rapture The transfiguration itself was brighter and whiter than man can comprehend. However, all the rest of the events in Mark 9 are dark and filled with fear. There is a demon possessed boy writhing and foaming at the mouth. The disciples are too afraid to ask Jesus questions. Jesus tells his disciples the Messiah must die. The chapter ends with the darkest sermon of all. Jesus teaches his disciples what they must do to keep themselves from going to hell. It is a sermon filled with a language of bodily mutilation and a description of everlasting fiery torture. -

In the Footsteps of Lord Jesus Christ Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, Nazareth, Haifa, Caesarea

In the Footsteps of Lord Jesus Christ Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, Nazareth, Haifa, Caesarea Day 1 – Depart U.S.A Day 7 – Jerusalem - Caesarea - Haifa - Day 2 – Tel Aviv - Jerusalem Mount of Transfiguration - Nazareth Depart Jerusalem and drive towards the Mediterranean coast. We stop in Day 3 – Mount of Olives - Gethsemane - Bethlehem - Shepherds’ Field ancient Caesarea to view the ruins and the Roman aqueduct. Then we go - Ein Karem to Haifa and Mount Carmel, where we visit the cave of the prophet Elijah, We start our day with the Mount of Olives for a magnificent view of the Old the Carmelite Monastery and enjoy a beautiful view of the coast and the City. We visit the Church of the Pater Noster, the Chapel of the Ascension city of Haifa. Continue to Mount Tabor, chosen by Jesus to be the site of and walk down to the Church of Dominus Flevit, passing by the Russian His transfiguration. Visit the Franciscan Church of the Transfiguration and Church and ending at the Garden of Gethsemane. We continue to Ein the Monastery. We arrive in Nazareth where we visit the Church of the Karem, known to be the birthplace of John the Baptist. After visiting the Annunciation, the church of St. Joseph and Mary’s Well. Church of the Visitation, we continue to Bethlehem. We visit the Church of the Nativity, the Holy Manger, the Basilica of St. Catherine and the Milk Day 8 – Cana - Tiberias - Sea of Galilee - Tabgha - Capernaum - Grotto. We drive down to the Shepherds’ Field where the angel of the Lord Mount of The Beatitudes - Caesarea Philippi appeared to the shepherds announcing the Good News. -

The Cities and Places Associated with the Ministry of Jesus Christ

Scholars Crossing The Second Person File Theological Studies 11-2017 The Cities and Places Associated with the Ministry of Jesus Christ Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "The Cities and Places Associated with the Ministry of Jesus Christ" (2017). The Second Person File. 58. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person/58 This The People and Places in the Jesus Christ Story is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Second Person File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CITIES AND PLACES ASSOCIATED WITH THE MINISTRY OF JESUS CHRIST BETHABARA A few miles north of Jericho, on the eastern bank of the Jordan River where John baptized Jesus (Jn. 1:28; Mt. 3:13-17) BETHANY Fifteen furlongs, or one and three-fourths miles from Jerusalem on the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives. It is on the road to Jericho. Bethany was the Judean headquarters of Jesus, as Capernaum was His Galilean headquarters. Here He raised Lazarus from the dead (Jn. 11). Mary and Martha entertained Christ here (Lk. 10:38-42). Mary anointed His feet here (Jn. 12:1-11). It was also the home of Simon the leper (Mk. 14:3). Here Christ blessed His disciples just prior to His ascension from the Mount of Olives (Lk. -

Miracles of Christ

MIRACLES OF CHRIST Menes Abdul Noor TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 THE FIRST MIRACLE TURNING WATER INTO WINE ................................................................ 2 THE SECOND MIRACLE HEALING THE NOBLEMAN'S SON ......................................................... 8 THE THIRD MIRACLE GREAT CATCH OF FISH ....................................................................... 14 THE FOURTH MIRACLE HEALING PETER'S MOTHER-IN-LAW .................................................. 20 THE FIFTH MIRACLE HEALING THE LEPER ............................................................................ 26 THE SIXTH MIRACLE HEALING THE PARALYTIC ................................................................... 32 THE SEVENTH MIRACLE HEALING THE SICK MAN AT THE POOL OF BETHESDA ................... 39 THE EIGHTH MIRACLE HEALING THE MAN WITH A WITHERED HAND ................................... 47 THE NINTH MIRACLE HEALING THE CENTURION'S SERVANT ............................................. 53 THE TENTH MIRACLE RAISING THE SON OF THE WIDOW OF NAIN ..................................... 59 THE ELEVENTH MIRACLE CALMING THE STORM .......................................................................... 65 THE TWELFTH MIRACLE HEALING THE MAN POSSESSED BY THE DEMON CALLED "LEGION" ................................................................................. 69 THE THIRTEENTH MIRACLE RAISING JAIRUS' DAUGHTER ............................................................. -

A Literary Guide to the Life of Christ in the Gospel According to Matthew

! ! A LITERARY GUIDE TO THE LIFE OF CHRIST IN THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO MATTHEW Matthew’s Portrait of Jesus The order of the four Gospels consistently reflected in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament is the same order found in our modern Bibles—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Appropriately, Matthew opens the New Testament canon even as Chronicles closes the Hebrew canon. Chronicles begins with an extensive genealogy and closes with a commission from King Cyrus to rebuild the earthly Jerusalem and its temple. Matthew, similarly, begins with a genealogy and ends with a commission from another King to fill the earth with disciples of the heavenly Jerusalem. The royal status of Matthew’s King is set as an inclusio in his Gospel from the opening question of the magi (“Where is He who is born King of the Jews?” 2:2) to the closing answer placarded on the cross (“This is Jesus the King of the Jews,” 27:37).17 As the closing of one canonical division is compared to the opening of another, Matthew directs our reading from the outset into a rich typology that finds fulfillment in Jesus. His Gospel is designed to seamlessly join the testaments through a typological reading that guides and informs the outcome of Old Testament expectations.18 Matthew artfully and seamlessly coalesces two themes in his portrait of Jesus, depicting Him as both a New Moses and a New Israel.19 The two themes are like magnets attracting each other since Moses was often viewed as representative of Israel and could even be viewed as a federal head of the nation since he was the human mediator of the covenant at Sinai. -

The Transfiguration: a Foretaste of Glory (Matthew 17:1-9, 2 Peter 1:16-21) Over These Past Few Weeks It's Been a Lot of Fun S

1 The Transfiguration: A Foretaste of Glory (Matthew 17:1-9, 2 Peter 1:16-21) Over these past few weeks it’s been a lot of fun seeing the photos of the Holy Land that many of our friends have been posting on Facebook. Michele and I briefly pondered whether we might have played some small part in so many of our friends going this year. And I kind of hope so, because we wanted to share the blessing. I have to admit that even with my undying gratitude for being able to make this trip a year ago, I felt just the slightest guilty twinge of envy when I noticed that for our friends every day seemed to be warm and sunny. Anyway, it’s all good. What brought all this to mind is that today is Transfiguration Sunday, and we visited the Church of the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor last year on a very cold, rainy, and windy day. In fact, as I vested for Eucharist in that great old church I made the mistake of laying my backpack on a window sill in the vesting room, and later returned to find it heroically soaking up as much water as it could from the puddle that had formed around it. So a cloud overshadowed Michele and me on the Mount of Transfiguration, but I’m pretty sure this isn’t like the one that shaded Jesus and the boys in today’s Gospel reading. And I find the account in Matthew’s Gospel to be awe-inspiring and solidly relevant to us apprentices of Jesus here this morning.