The Case of Atwood's Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Electricity

THE LEYDEN JAR 0. THE LEYDEN JAR - Story Preface 1. EARLY PIONEERS 2. EARLY EXPERIMENTS 3. THE LEYDEN JAR 4. LIGHTNING in a BOTTLE 5. ELECTRICITY and the TORPEDO FISH 6. MEET GALVANI and VOLTA 7. WHAT MAKES a FROG'S LEG TWITCH? 8. THE WORLD'S FIRST BATTERY 9. THE END and BEGINNING of an ERA In 1746, while visiting Professor Pieter van Musschenbroek’s lab in Leiden (The Netherlands), Andreas Cuneus (a Dutch lawyer, scientist and erstwhile Professor’s assistant) received an extremely powerful shock. This artist’s conception depicts Cuneus, in the lab, attempting to condense electricity in a glass of water. When he tried to pull the wire out of the water, Cuneus was stunned by the magnitude of the shock he received (since it was much worse than that produced by an electrostatic generator, seen on the right side of the drawing). It took him two days to recover. The illustration is Figure 382, at page 570 of Elementary Treatise on Natural Philosophy, Part 3: Electricity and Magnetism, by Augustin Privat Deschanel (translated and edited by J. D. Everett), published in New York, during 1876, by D. Appleton and Co. Online via Google Books. Early experimenters, trying to understand electricity, wondered about its properties: If electricity flows (like water), could it be stored (like water)? Since glass is an insulator, could electricity be stored in a glass jar? If we pour water into a glass jar, then we position a metal wire into the water-containing jar - hooked, at the top, to a Hauksbee electrostatic generator - what would happen? Pieter Van Musschenbroek (a Professor working at Leiden University, in The Netherlands) was particularly keen to store electricity. -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

Lecture Notes on Classical Mechanics for Physics 106Ab Sunil Golwala

Lecture Notes on Classical Mechanics for Physics 106ab Sunil Golwala Revision Date: September 25, 2006 Introduction These notes were written during the Fall, 2004, and Winter, 2005, terms. They are indeed lecture notes – I literally lecture from these notes. They combine material from Hand and Finch (mostly), Thornton, and Goldstein, but cover the material in a different order than any one of these texts and deviate from them widely in some places and less so in others. The reader will no doubt ask the question I asked myself many times while writing these notes: why bother? There are a large number of mechanics textbooks available all covering this very standard material, complete with worked examples and end-of-chapter problems. I can only defend myself by saying that all teachers understand their material in a slightly different way and it is very difficult to teach from someone else’s point of view – it’s like walking in shoes that are two sizes wrong. It is inevitable that every teacher will want to present some of the material in a way that differs from the available texts. These notes simply put my particular presentation down on the page for your reference. These notes are not a substitute for a proper textbook; I have not provided nearly as many examples or illustrations, and have provided no exercises. They are a supplement. I suggest you skim them in parallel while reading one of the recommended texts for the course, focusing your attention on places where these notes deviate from the texts. ii Contents 1 Elementary Mechanics 1 1.1 Newtonian Mechanics .................................. -

Lorentz – Function Follows Form and Theory Leads to Experiment

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22522 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Weiss, Martin Paul Michael Title: The masses and the muses : a history of Teylers Museum in the Nineteenth Century Issue Date: 2013-11-27 The Masses and the Muses A History of Teylers Museum in the Nineteenth Century Front cover: The Oval Room, drawing by Johan Conrad Greive, 1862 (Teylers Museum, Haarlem, DD042b) Back cover: The First Art Gallery, drawing by Johan Conrad Greive, 1862 (Teylers Museum, Haarlem, DD042d) The Masses and the Muses A History of Teylers Museum in the Nineteenth Century Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 27 november 2013 klokke 15.00 uur door Martin Paul Michael Weiss geboren te Hannover in 1985 Promotiecommissie Prof. Dr. F.H. van Lunteren (promotor, Universiteit Leiden) Prof. Dr. D. van Delft (Universiteit Leiden) Prof. Dr. P.J. ter Keurs (Universiteit Leiden) Dr. D.J. Meijers (Universiteit van Amsterdam) Prof. dr. W.W. Mijnhardt (Universiteit Utrecht) Prof. Dr. H.J.A. Röttgering (Universiteit Leiden) Prof. Dr. L.T.G. Theunissen (Universiteit Utrecht) Dr. H.J. Zuidervaart (Huygens Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis) Prof. Dr. R. Zwijnenberg (Universiteit Leiden) Acknowledgements This PhD was not written in isolation. Throughout the course of this project I received an unquantifiable amount of support – intellectual, financial and moral – from innumerable colleagues and friends. Some of them I hope to be able to acknowledge here. -

– by Julia Cipo, Holger Kersten –

THE GAS DISCHARGE PHYSICS IN THE 18th CENTURY – by Julia Cipo, Holger Kersten – Francis Edmond Hauksbee Halley * 1666 in Colchester, Great Britain † April/ May 1713 in London * November 8th, 1656 in Haggerston, London † January 25th, 1742 in Greenwich Francis Hauksbee was a british scientist, lab assistant of Isaac Newton *4 and an elected member of the Royal Society for researches in science. Edmond Halley was a british astro- ric (height) formula. In 1716 a bright physicist, meteorologist, mathemati- Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) ing from the North Pole to the South Inspired by Picard’s and Bernoulli’s results on the luminosity of mercu- cian and member of the Royal So- was sighted in Germany, England, Pole. Even though this wasn’t correct, ry in barometric tubes, Hauksbee continued experimenting with mercu- ciety. As the earth’s magnetic fi eld France and Holland. Halley began he determined that the aurora’s arc ry with one difference: he examined the probe in a vacuum vessel. In fascinated him, he worked on this searching for a scientifi c explana- did not course along the geographic his 1709 publicated work topic during the years 1683-1710 tion of this phenomena. He suggest- pole, but along the magnetic pole. *1 called “Physio-mechanical and discovered the line profi le of the ed that the aurora was caused by an experiments on various Hauksbee’s generator magnetic fi eld as well as the baromet- evaporation of magnetic liquid mov- subjects touching light and electricity” he described that after placing mercu- ry in the glass vessel and then evacuating the air, a bright glow could be sight- ed. -

Jean-Baptiste Sarlandie`Re's Mechanical Leeches (1817–1825): an Early Response in the Netherlands to a Shortage of Leeches

Medical History, 2009, 53: 253–270 Jean-Baptiste Sarlandie`re’s Mechanical Leeches (1817–1825): An Early Response in the Netherlands to a Shortage of Leeches TEUNIS WILLEM VAN HEININGEN* Introduction At the end of the eighteenth century there was a rapidly growing demand for leeches in Europe. Western European and Central European freshwater species had been mainly used until then but now more and more different species were introduced.1 England imported large numbers from Eastern Europe and the Levant, and Pondicherry in Southern India was an important centre for the shipment of these animals whose application was considered a mild form of bloodletting.2 In the autumn of 1825 the Algemeene Konst- en Letterbode, a Dutch weekly journal, drew attention to a shortage, informing its readers that large numbers, kept for medical purposes, had died without an apparent cause,3 possibly through an unknown infective agent. It also printed information by a German pharmacist from Kassel on the proper method of keeping leeches alive as long as possible in large aquaria, by including water plants.4 One solution to the problem had already been invented—the artificial leech of Jean- Baptiste Sarlandie`re. At their annual general meeting, held on 21 May 1821, the officers of the Dutch Society of Sciences (Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen, founded in 1752), on learning of Sarlandie`re’s invention through Martinus van Marum, the Society’s secretary, decided to hold a competition on its serviceability.5 They were persuaded by the increasing demand for leeches, as well as by the fascinating and pro- mising aspects and originality of Sarlandie`re’s invention. -

Cover Page the Handle

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22522 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Weiss, Martin Paul Michael Title: The masses and the muses : a history of Teylers Museum in the Nineteenth Century Issue Date: 2013-11-27 Chapter II: The Birth of a Musaeum I The Museum’s Pre-History 1. Martinus van Marum & the Beginning of the Age of Museums In a letter to the Dutch minister of the interior Anton Reinhard Falck posted in July 1819, the ornithologist and collector Coenraad Jacob Temminck left no doubt as to what he thought two of his colleagues really wanted to do to him, if the opportunity ever presented itself: “Both”, he wrote, “would stop at nothing to clear me out of the way”.1 He was referring to Sebald Justinus Brugmans, professor of botany and director of the botanical gardens in Leiden, and Martinus van Marum, the director of Teylers Museum and secretary of the Holland Society of Sciences in Haarlem. This was more than just a letter of complaint. Temminck himself was no angel, and at the time was in fact pursuing his own political agenda. He had dined with Falck just a few days earlier, and the two men had discussed the establishment of a national museum of natural history in the Netherlands – of which Temminck was to be handed the directorship. Just 13 months later, Temminck’s highly valuable and widely recognised personal ornithological collection, consisting of more than 4000 stuffed birds, had indeed been merged with both the University of Leiden’s natural history collections and the former Royal Cabinet of Natural History in Amsterdam, to form the new National Museum of Natural History (Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie) based in Leiden. -

Cum Ferme Omnes Ante Cartesium Arbitrarentur, Primam Humanae

General Theses from Physics As Taught in the Clementine College Don Alexandro Malaspina of the Imperial Marquisate of Mulazzo, Member of the said College. Facta cuilibet singulas impugnandi facultate. [Great deeds are achieved by attacking them singly.] ____________________________________________________________________ Rome 1771 From the Press of Lorenzo Capponi. ___________________________________________ With the Sanction of the Higher Authorities. 1 Of the Principles of Education in Physics Since the serious study of a philosophical man looks above all to this end, that he might achieve certainty and clear knowledge of things, we ourselves have taken pains at the outset to render an account according to reason, so that through our careful investigation of physics, the mind might thus be drawn towards Nature. Of physicists, we consider, with John Keill,a,1 four schools to be pre-eminent among the rest, the first being the Pythagoreans and Platonists; another has its origin in the Peripatetic School;2 the third tribe of Philosophisers pursues the experimental method; and the final class of physicists is commonly known as the Mechanists. While not all that is propounded by these schools is worthy of assent, yet in each there are certain things of which we approve, abhorring as we do the fault with which Leibniz charges the Cartesians,b,3 namely that of judging the ancient authors with contempt, punishing them, as it were, according to one’s own law. And since Those things last long, and are fixed firmly in the mind, Which we, once born, have imbibed from our earliest years, we select what will be of most use in the future, and of all this we present to our scholars an ordered account: no one would think it suitable for us to hear or read anything contrary to method,c,4 for in general it is through habit, and especially through philosophical habit, that youth is first instructed in the colleges. -

The Lagrangian Method Copyright 2007 by David Morin, [email protected] (Draft Version)

Chapter 6 The Lagrangian Method Copyright 2007 by David Morin, [email protected] (draft version) In this chapter, we're going to learn about a whole new way of looking at things. Consider the system of a mass on the end of a spring. We can analyze this, of course, by using F = ma to write down mxÄ = ¡kx. The solutions to this equation are sinusoidal functions, as we well know. We can, however, ¯gure things out by using another method which doesn't explicitly use F = ma. In many (in fact, probably most) physical situations, this new method is far superior to using F = ma. You will soon discover this for yourself when you tackle the problems and exercises for this chapter. We will present our new method by ¯rst stating its rules (without any justi¯cation) and showing that they somehow end up magically giving the correct answer. We will then give the method proper justi¯cation. 6.1 The Euler-Lagrange equations Here is the procedure. Consider the following seemingly silly combination of the kinetic and potential energies (T and V , respectively), L ´ T ¡ V: (6.1) This is called the Lagrangian. Yes, there is a minus sign in the de¯nition (a plus sign would simply give the total energy). In the problem of a mass on the end of a spring, T = mx_ 2=2 and V = kx2=2, so we have 1 1 L = mx_ 2 ¡ kx2: (6.2) 2 2 Now write µ ¶ d @L @L = : (6.3) dt @x_ @x Don't worry, we'll show you in Section 6.2 where this comes from. -

8.012 Physics I: Classical Mechanics Fall 2008

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 8.012 Physics I: Classical Mechanics Fall 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Physics Physics 8.012 Fall 2008 Exam 3 NAME: _________________S___OL___U____TIO___NS___ ________________ Instructions: 1. Do all FIVE (5) problems. You have 90 minutes. 2. SHOW ALL WORK. Be sure to circle your final answer. 3. Read the questions carefully. 4. All work must be done in this booklet in workspace provided. Extra blank pages are provided at the end if needed. 5. NO books, notes, calculators or computers are permitted. A sheet of useful equations is provided on the last page. Your Scores Problem Maximum Score Grader 1 10 2 20 3 25 4 25 5 20 Total 100 8.012 Fall 2007 Quiz 3 Problem 1: Quick Multiple Choice Questions [10 pts] For each of the following questions circle the correct answer. You do not need to show any work. (a) [2 pts] A bicycle rider pedals up a hill with constant velocity v. In which direction does friction act on the wheels? Friction does not act while the Uphill Downhill bike moves at constant velocity Friction provides the only support against falling downhill, so it must point up. (b) [2 pts] A gyroscope is set to spin so that its ! spin vector points back to the mount. The gryoscope is initially set at an angle α below horizontal and released from rest. Gravity acts downward. In which direction does the precession angular velocity vector point once the gyroscope starts to precess? Up Down Into the page Out of the page The initial fall of the gyroscope causes the spin vector to point up. -

Classical Mechanics an Introductory Course

Classical Mechanics An introductory course Richard Fitzpatrick Associate Professor of Physics The University of Texas at Austin Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Major sources: . 7 1.2 What is classical mechanics? . 7 1.3 mks units . 9 1.4 Standard prefixes . 10 1.5 Other units . 11 1.6 Precision and significant figures . 12 1.7 Dimensional analysis . 12 2 Motion in 1 dimension 18 2.1 Introduction . 18 2.2 Displacement . 18 2.3 Velocity . 19 2.4 Acceleration . 21 2.5 Motion with constant velocity . 23 2.6 Motion with constant acceleration . 24 2.7 Free-fall under gravity . 26 3 Motion in 3 dimensions 32 3.1 Introduction . 32 3.2 Cartesian coordinates . 32 3.3 Vector displacement . 33 3.4 Vector addition . 34 3.5 Vector magnitude . 35 2 3.6 Scalar multiplication . 35 3.7 Diagonals of a parallelogram . 36 3.8 Vector velocity and vector acceleration . 37 3.9 Motion with constant velocity . 39 3.10 Motion with constant acceleration . 39 3.11 Projectile motion . 41 3.12 Relative velocity . 44 4 Newton's laws of motion 53 4.1 Introduction . 53 4.2 Newton's first law of motion . 53 4.3 Newton's second law of motion . 54 4.4 Hooke's law . 55 4.5 Newton's third law of motion . 56 4.6 Mass and weight . 57 4.7 Strings, pulleys, and inclines . 60 4.8 Friction . 67 4.9 Frames of reference . 70 5 Conservation of energy 78 5.1 Introduction . 78 5.2 Energy conservation during free-fall . -

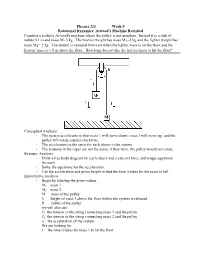

Physics 211 Week 9 Rotational Dynamics: Atwood's Machine Revisited Consider a Realistic Atwood's Machine Where the Pulley Is Not Massless

Physics 211 Week 9 Rotational Dynamics: Atwood's Machine Revisited Consider a realistic Atwood's machine where the pulley is not massless. Instead it is a disk of radius 0.1 m and mass M=3 kg. The heavier weight has mass M1=5 kg and the lighter weight has mass M2= 2 kg. The system is released from rest when the lighter mass is on the floor and the heavier mass is 1.8 m above the floor. How long does it take the heavier mass to hit the floor? Conceptual Analysis: - The system accelerates so that mass 1 will move down, mass 2 will move up, and the pulley will rotate counter clockwise. - The acceleration is the same for each object in the system. - The tensions in the ropes are not the same, if they were, the pulley would not rotate. Strategic Analysis: - Draw a free body diagram for each object and create net force and torque equations for each. - Solve the equations for the acceleration. - Use the acceleration and given height to find the time it takes for the mass to fall. Quantitative Analysis: - Begin by labeling the given values: M1 mass 1 M2 mass 2 M mass of the pulley h height of mass 1 above the floor before the system is released R radius of the pulley we will also use T1 the tension in the string connecting mass 1 and the pulley T2 the tension in the string connecting mass 2 and the pulley a the acceleration of the system We are looking for t the time it takes for mass 1 to hit the floor - We'll begin by drawing a free body diagram for each mass.