Occurrence of the Eastern Hellbender in the Coosawattee River System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

Chemical Character of Surface Waters of Georgia

SliEU' :\0..... / ........ RO O ~ l NO. ···- ··-<~ ......... U )'On no l~er need this publication write to the Geological Sur»ey in Washlndon for ali official maillne label to use In returning it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA Prepared In cooperation wilh the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF 'l'HE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 889- E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 889-E CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA BY WILLIAM L. LAMAR Prepared in cooperation with the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 19~1-!3 (Pages 317- 380) UN ITED STATES GOVEHNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 For sct le Ly Ll w S upcrinkntlent of Doc uments, U. S. Gover nme nt Printing Office, " ' asbingtou 25, D . C. Price 15 ce nl~ CONTENTS Page- Abstract ___________________________________________ -----_--------- 31 T Introduction __________________ c ________________________________ -- _ 317 Physiography_____________________________________________________ 318 Climate__________________________________________________________ 820 Collection and examination of samples_______________________________ 323 Stream flow __________________________ --------- ___________ c ________ . 324 Rainfall and discharge during sampling years_____________________ -

Plan for Coosawattee River HUC 10# 0315010204

Plan for Coosawattee River HUC 10# 0315010204 STATE OF GEORGIA TIER 2 TMDL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REVISION 1 Segment Name Coosawattee River Coosa River Basin April 28, 2006 Local Watershed Governments Gilmer County and Cities of Ellijay and East Ellijay I. INTRODUCTION Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plans are platforms for evaluating and tracking water quality protection and restoration. These plans have been designed to accommodate continual updates and revisions as new conditions and information warrant. In addition, field verification of watershed characteristics and listing data has been built into the preparation of the plans. The overall goal of the plans is to define a set of actions that will help achieve water quality standards in the state of Georgia. This implementation plan addresses the general characterist ics of the watershed, the sources of pollution, stakeholder s and public involvement, and education/o utreach activities. In addition, the plan describes regulatory and voluntary practices/control actions (management measures) to reduce pollutants, milestone schedules to show the development of the managemen t measures (measurable milestones), and a monitoring plan to determine the efficiency of the management measures. Table 1. IMPAIRMENTS IMPAIRED STREAM SEGMENT IMPAIRED SEGMENT LOCATION IMPAIRMENT TMDL ID Confluence with Ellijay River to Mountaintown CSA0000011 Coosawattee River Fecal Coliform Bacteria Creek 06022812.004 CEDS TMDL 1 Plan for Coosawattee River HUC 10# 0315010204 II. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE WATERSHED Write a narrative describing the watershed, HUC 10# 0315010204. Include an updated overview of watershed characteristics. Identify new conditions and verify or correct information in the TMDL document using the most current data. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Riverview Farms

Georgia’s 2018 CLEAN WATER HEROES Riverview Farms COOSAWATTEE RIVER Organic Family Farm Leaves Clean Water Legacy INTRODUCTION: On the Coosawattee River in north Georgia, it’s not uncommon to see livestock crowded along the banks drinking from (and defecating in) the river. For river users looking for a cool, refreshing swim in those same waters, the question often arises; “Isn’t there a law against that?” The answer is “No.” When it comes to Georgia lawmakers, agriculture is, pardon the pun, a sacred cow, COOSAWATTEE exempt from many fundamental clean water regulations. But at least for one RIVER mile along the Coosawattee in rural Gordon County, you’ll never see a cow in the river. That’s because the Swancy family at Riverview Farms, one of the state’s largest certified organic farms, serve as stewards of the river by observing state buffer laws (from which farmers are exempt), and excluding livestock from water bodies on the farm. As proprietor Charlotte Swancy said: “We don’t want our animals in the water. That just doesn’t seem right. People drink that water.” THE WATER BODY: The Coosawattee River does, in fact, serve as the drinking water source for Gordon County and Calhoun just downstream from Riverview Farms. Formed by the gathering of the Ellijay and Cartecay rivers near Ellijay, the Coosawattee flows out of the north Georgia mountains and some 50 miles to join the Conasauga River near Calhoun and form the Oostanaula. Along the way, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operates Carters Lake and Dam, which at 445 feet in height, is considered the tallest earthen dam east of the Mississippi River. -

Underwater Observation and Habitat Utilization of Three Rare Darters

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2010 Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee Robert Trenton Jett University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Jett, Robert Trenton, "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Robert Trenton Jett entitled "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. James L. Wilson, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Etnier, Jason G. -

Streamflow Maps of Georgia's Major Rivers

GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 21 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson United States Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1960 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson Maps are commonly used to show the approximate rates of flow at all localities along the river systems. In addition to average flow, this collection of streamflow maps of Georgia's major rivers shows features such as low flows, flood flows, storage requirements, water power, the effects of storage reservoirs and power operations, and some comparisons of streamflows in different parts of the State. Most of the information shown on the streamflow maps was taken from "The Availability and use of Water in Georgia" by M. T. Thomson, S. M. Herrick, Eugene Brown, and others pub lished as Bulletin No. 65 in December 1956 by the Georgia Department of Mines, Mining and Geo logy. The average flows reported in that publication and sho\vn on these maps were for the years 1937-1955. That publication should be consulted for detailed information. More recent streamflow information may be obtained from the Atlanta District Office of the Surface Water Branch, Water Resources Division, U. S. Geological Survey, 805 Peachtree Street, N.E., Room 609, Atlanta 8, Georgia. In order to show the streamflows and other features clearly, the river locations are distorted slightly, their lengths are not to scale, and some features are shown by block-like patterns. -

Affect Space Use by Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus Coccogenis)

Received: 26 February 2018 | Revised: 16 July 2018 | Accepted: 19 July 2018 DOI: 10.1111/eff.12440 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Stocked rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) affect space use by Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus coccogenis) Duncan Elkins | Nathan P. Nibbelink | Gary D. Grossman Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Abstract Georgia Due to widespread stocking, Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum) are per- Correspondence haps the most widely distributed invasive species in the world. Nonetheless, little is Gary D. Grossman, Warnell School of known about the effects of stocked Rainbow Trout on native non- game species. We Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. conducted experiments in an artificial stream to assess the effects of hatchery Email: [email protected] Rainbow Trout on home range and behaviour of Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus coccogenis Funding information Cope), a common minnow frequently found in stocked Southern Appalachian Georgia Department of Natural Resources, streams. We used the LoCoH algorithm to generate polygons describing the home Grant/Award Number: 2021RR272; Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources; ranges used by Warpaint Shiners. When a stocked trout was present Warpaint USDA McIntire-Stennis Program, Grant/ Shiners: (a) increased home range size by 57%, (b) were displaced into higher velocity Award Number: GEOZ-0176-MS Grossman mesohabitats, and (c) reduced mean overlap between the home ranges of individual warpaint shiners. Rainbow Trout did not significantly affect the edge/area ratio of Warpaint Shiner home ranges. Warpaint Shiner density (two and five fish treatments) did not significantly affect any response variable. Displacement from preferred mi- crohabitats and increases in home range size likely result in increased energy ex- penditure and exposure to potential predators (i.e., decreased individual fitness) of Warpaint Shiners when stocked trout are present. -

July 3-9, 2011

Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Law Enforcement Section Field Operations Weekly Report July 3-9, 2011 This report is a broad sampling of events that have taken place in the past week, but does not include all actions taken by the Law Enforcement Section. Region I- Calhoun (Northwest) FLOYD COUNTY On Sunday June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was working along the Etowah River in Rome and overheard radio traffic from Rome PD about a vehicle getting broken into at the Etowah River boat ramp. Cpl. Elmore responded to the boat ramp and assisted Rome PD officer. Cpl. Elmore located one of the suspects hiding in the woods and the other suspect came out of the river. Three juvenile suspects were detained and charged with entering an auto and criminal damage to property by Rome PD. On June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was at the Heritage Park boat ramp on the Coosa River in Rome when he was approached by a parent of four teenagers that were caught in a storm on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore went to get his patrol vessel and while enroute to the Etowah River boat ramp the four teens called the parents and advised they had gotten out of the river safely and were waiting on a ride on Turner Chapel Rd. On the night of June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore received a call from Floyd E911 about 3 adults and a 3 year-old child stranded on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore responded to the scene and assisted Rome/Floyd Fire with a search of the river and the four were located and safely returned to their vehicle. -

Aquatic Biota

Low Gradient, Cool, Headwaters and Creeks Macrogroup: Headwaters and Creeks Shawsheen River, © John Phelan Ecologist or State Fish Game Agency for more information about this habitat. This map is based on a model and has had little field-checking. Contact your State Natural Heritage Description: Cool, slow-moving, headwaters and creeks of low-moderate elevation flat, marshy settings. These small streams of moderate to low elevations occur on flats or very gentle slopes in watersheds less than 39 sq.mi in size. The cool slow-moving waters may have high turbidity and be somewhat poorly oxygenated. Instream habitats are dominated by glide-pool and ripple-dune systems with runs interspersed by pools and a few short or no distinct riffles. Bed materials are predominenly sands, silt, and only isolated amounts of gravel. These low-gradient streams may have high sinuosity but are usually only slightly entrenched with adjacent Source: 1:100k NHD+ (USGS 2006), >= 1 sq.mi. drainage area floodplain and riparian wetland ecosystems. Cool water State Distribution:CT, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, VA, temperatures in these streams means the fish community WV contains a higher proportion of cool and warm water species relative to coldwater species. Additional variation in the stream Total Habitat (mi): 16,579 biological community is associated with acidic, calcareous, and neutral geologic settings where the pH of the water will limit the % Conserved: 11.5 Unit = Acres of 100m Riparian Buffer distribution of certain macroinvertebrates, plants, and other aquatic biota. The habitat can be further subdivided into 1) State State Miles of Acres Acres Total Acres headwaters that drain watersheds less than 4 sq.mi, and have an Habitat % Habitat GAP 1 - 2 GAP 3 Unsecured average bankfull width of 16 feet or 2) Creeks that include larger NY 41 6830 94 325 4726 streams with watersheds up to 39 sq.mi. -

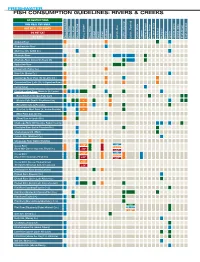

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

River Basin Profiles

APPENDIX A River Basin Profiles The River Basin Profiles (RBPs) are intended to provide watershed-based information and perspectives on potential management issues within each of the Metro Water District’s HUC-8 watersheds. Each profile contains information regarding physical and natural features, land use, population, impaired waterbodies, management issues, and strategies to address those issues. While the strategies contained within the RBP are not required for implementation, they serve as a guide for the types of actions that can be used to address water management issues, primarily within the realm of nonpoint source management. Action Item WATERSHED-8 requires that local governments carry out Watershed Improvement Projects and many jurisdictions develop watershed improvement plans to help direct where and what kinds of projects they carry out. Jurisdictions should look to the RBPs as a starting point for local watershed planning. Additionally, jurisdictions can use the information in the RBP as a foundation for 9-Element Watershed Plans, which are required for a Section 319(h) Implementation Grant. In addition to being a foundational source of information for localized planning, RBPs also provide a high- level perspective of each basin. This high-level perspective further reinforces the interconnectedness of the various water sectors (supply, waste, storm, etc.) and brings in additional elements such as land use. The RBPs do not get into specific details on each subwatershed, allowing for a high-level integration to guide local