The Dead Sea Scrolls Case - Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

Frank Moore Cross's Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Classics and Religious Studies Department 2014 Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls" (2014). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 127. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford This paper examines the impact of Frank Moore Cross on the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Since Cross was a member of the original editorial team responsible for publishing the Cave 4 materials, his influence on the field was vast. The article is limited to those areas of Scrolls study not covered in other articles; the reader is referred especially to the articles on palaeography and textual criticism for further discussion of Cross’s work on the Scrolls. t is difficult to overestimate the impact the discovery They icturedp two columns of a manuscript, columns of of the Dead Sea Scrolls had on the life and career of the Book of Isaiah . -

Qumran Caves” in the Iron Age in the Light of the Pottery Evidence

CHAPTER 17 History of the “Qumran Caves” in the Iron Age in the Light of the Pottery Evidence Mariusz Burdajewicz Since the late ‘40s and the beginning of the ‘50s of the last Jerusalem carried out a survey of about 270 sites situated century, the north-eastern part of the Judean Desert has to the north and south of the Qumran site.4 Of the 40 sites been witnessing numerous archaeological surveys and (almost exclusively caves or cavities), where the traces of works (Table 17.1; Fig. 17.1). The main, but not the only one, human presence from various periods were found, only goal of various expeditions sent to the Dead Sea region, few of them yielded the finds pertaining to the Iron Age. was the quest for more and more scrolls. On this occasion, One large bowl and one lamp came from caves GQ 27 and apart from manuscripts, many other artefacts, like pottery GQ 39 respectively.5 Fragments of two vessels dated to the and the so-called small finds,1 have come to light. Their Iron Age II are mentioned as coming from cave GQ 13, and chronology range in date from the Chalcolithic to the a few pottery sherds, possibly dated to the same period, Arab periods. from cave GQ 6.6 The survey was completed in 1956, and The aim of this short paper is to present, on the basis of some additional pottery fragments from the Iron Age pottery evidence, some observations concerning the use were found in cave 11Q (fragments of jars, two lamps and of the caves during the Iron Age II–III. -

History and Narrative in a Changing Society: James Henry Breasted and the Writing of Ancient Egyptian History in Early Twentieth Century America

History and Narrative in a Changing Society: James Henry Breasted and the Writing of Ancient Egyptian History in Early Twentieth Century America by Lindsay J. Ambridge A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Janet E. Richards, Chair Professor Carla M. Sinopoli Associate Professor Terry G. Wilfong Emily Teeter, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago © Lindsay J. Ambridge All rights reserved 2010 Acknowledgments The first person I would like to thank is my advisor and dissertation committee chair, Janet Richards, who has been my primary source of guidance from my first days at the University of Michigan. She has been relentlessly supportive not only of my intellectual interests, but also in securing fieldwork opportunities and funding throughout my graduate career. For the experiences I had over the course of four expeditions in Egypt, I am deeply grateful to her. Most importantly, she is always kind and unfailingly gracious. Terry Wilfong has been a consistent source of support, advice, and encyclopedic knowledge. His feedback, from my first year of graduate school to my last, has been invaluable. He is generous in giving advice, particularly on matters of language, style, and source material. It is not an overstatement to say that the completion of this dissertation was made possible by Janet and Terry’s combined resourcefulness and unflagging support. It is to Janet and Terry also that I owe the many opportunities I have had to teach at U of M. Working with them was always a pleasure. -

Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: a Question of Access

690 American Archivist / Vol. 56 / Fall 1993 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/56/4/690/2748590/aarc_56_4_w213201818211541.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Question of Access SARA S. HODSON Abstract: The announcement by the Huntington Library in September 1991 of its decision to open for unrestricted research its photographs of the Dead Sea Scrolls touched off a battle of wills between the library and the official team of scrolls editors, as well as a blitz of media publicity. The action was based on a commitment to the principle of intellectual freedom, but it must also be considered in light of the ethics of donor agreements and of access restrictions. The author relates the story of the events leading to the Huntington's move and its aftermath, and she analyzes the issues involved. About the author: Sara S. Hodson is curator of literary manuscripts at the Huntington Library. Her articles have appeared in Rare Books & Manuscripts Librarianship, Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook, and the Huntington Library Quarterly. This article is revised from a paper delivered before the Manuscripts Repositories Section meeting of the 1992 Society of American Archivists conference in Montreal. The author wishes to thank William A. Moffett for his encour- agement and his thoughtful and invaluable review of this article in its several revisions. Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls 691 ON 22 SEPTEMBER 1991, THE HUNTINGTON scrolls for historical scholarship lies in their LIBRARY set off a media bomb of cata- status as sources contemporary with the time clysmic proportions when it announced that they illuminate. -

Bible from Qumran Sidnie White Crawford

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sidnie White Crawford Publications Classics and Religious Studies 2014 The O" ther" Bible from Qumran Sidnie White Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/crawfordpubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sidnie White Crawford Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The "Other" Bible from Qumran by Sidnie White Crawford Where did the Bible come from? The Hebrew Bible, or Christian Old Testament, did not exist in the canonical form we know prior to the early second century C.E. Before that, certain books had become authoritative in the Jewish community, but the status of other books, which eventually did become part of the Hebrew Bible, was questionable. All Jews everywhere, since at least the fourth century B.C.E., accepted the authority of the Torah of Moses, the first five books of the Bible (also called the Pentateuch): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Most Jews also accepted the books of the Prophets, including the Former Prophets or historical books (Joshua through Kings), as authoritative. The Samaritan community only accepted the Pentateuch as authoritative, and the Pentateuch remains their Bible today. Some parts of the Jewish community accepted the books found in the Writings as authoritative, but not all Jews accepted all of those books. The Jewish community that lived at Qumran and stored their manuscripts in the nearby caves, for example, do not seem to have accepted Esther as authoritative. -

Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 2007 Volume 25 Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places STEPHEN PFANN In December 1952, five years after the discovery of Qumran cave 1, Roland de Vaux connected its manuscript remains to the nearby site of Khirbet Qumran when he found one of the unique cylindrical jars, typical of cave 1Q, embedded in the floor of the site. The power of this suggestion was such that, from that point on, as each successive Judean Desert cave containing first-century scrolls was discovered, they, too, were assumed to have originated from the site of Qumran. Even the scrolls discovered at Masada were thought to have arrived there by the hands of Essene refugees. Other researchers have since proposed that certain teachings within the scrolls of Qumran’s caves provide evidence for a sect that does not match that of the Essenes described by first-century writers such as Josephus, Philo and Pliny. These researchers prefer to call this group ‘the Qumran Community’, ‘the Covenanters’, ‘the Yahad ’ or simply ‘sectarians’. The problem is that no single title sufficiently covers the doctrines presented in the scrolls, primarily since there is a clear diversity in doctrine among these scrolls.1 In this article, I would like to present a challenge to this monolithic approach to the understanding of the caves and their scroll collections. This reassessment will be based on a close examination of the material culture of the caves (including ceramics and fabrics) and the palaeographic dating of the scroll collections in individual caves. -

The Concept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 2010 The onceptC of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant Jintae Kim Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Jintae, "The oncC ept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant" (2010). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 374. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/374 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [JGRChJ 7 (2010) 98-111] THE CONCEPT OF ATONEMENT IN THE QUMRAN LITERatURE AND THE NEW COVENANT Jintae Kim Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, Lynchburg, VA Since their first discovery in 1947, the Qumran Scrolls have drawn tremendous scholarly attention. One of the centers of the early discussion was whether one could find clues to the origin of Christianity in the Qumran literature.1 Among the areas of discussion were the possible connections between the Qumran literature and the New Testament con- cept of atonement.2 No overall consensus has yet been reached among scholars concerning this issue. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

4Qmmt) and Its Addressee(S)

CHAPTER FOUR TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: MIQSAṬ MAʿAŚE HA-TORAH (4QMMT) AND ITS ADDRESSEE(S) 1. Introduction Long before its official publication in 1994,1 and even before its debut in 1984,2 4QMMT had been characterized as a polemical communi- cation (or “letter”) between the sectarian leadership of the Qumran community, or some precursor, and the mainstream priestly or Phari- saic leadership in Jerusalem.3 This framing of the document overall 1 Elisha Qimron and John Strugnell, Qumran Cave 4. V: Miqsaṭ Maʿaśe Ha-Torah (DJD X; Oxford: Clarendon, 1994), henceforth referred to as DJD X. 2 See articles jointly authored by Qimron and Strugnell in next note. 3 For a concise statement of the generally held view of 4QMMT, see James C. VanderKam, The Dead Sea Scrolls Today (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1994), 59–60. The earliest notices of 4QMMT are as follows: Pierre Benoit et al., “Editing the Manuscript Fragments from Qumran,” BA 19 (1956): 94 (report of John Strugnell, August 1955; the same in French in RB 63 [1956]: 65); Józef T. Milik, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judea (trans. J. Strugnell; London: SCM, 1959; French orig., 1957), 41, 130; idem, “Le travail d’édition des manuscrits du Désert de Juda,” in Volume du Congrès, Strasbourg 1956 (VTSup 4; Leiden: Brill, 1957), 24; idem, in DJD III (1962): 225; Joseph M. Baumgarten, “The Pharisaic-Sadducean Controversies about Purity and the Qumran Texts,” JJS 31 (1980): 163–64; Yigael Yadin, ed., The Temple Scroll (3 vols.; Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1983), 2.213; Elisha Qim- ron and John Strugnell, “An Unpublished Halakhic Letter from Qumran,” in Biblical Archaeology Today: Proceedings of the International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, April 1984 (ed. -

University of Birmingham the Profile and Character of Qumran

University of Birmingham The Profile and Character of Qumran Cave 4 Hempel, Charlotte DOI: 10.1163/9789004316508_006 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Hempel, C 2016, The Profile and Character of Qumran Cave 4: The Community Rule Manuscripts as a Test Case. in M Fidanzio (ed.), The Caves of Qumran: Proceedings of the International Conference, Lugano 2014. STDJ, vol. 118, Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004316508_006 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Publisher conditions checked General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

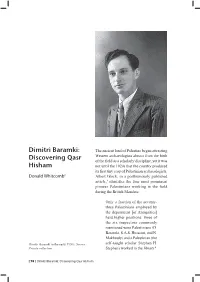

Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham1

Dimitri Baramki: The ancient land of Palestine began attracting Western archaeologists almost from the birth Discovering Qasr of the field as a scholarly discipline, yet it was Hisham1 not until the 1920s that the country produced its first tiny crop of Palestinian archaeologists. Donald Whitcomb2 Albert Glock, in a posthumously published article,3 identifies the four most prominent pioneer Palestinians working in the field during the British Mandate: Only a fraction of the seventy- three Palestinians employed by the department [of Antiquities] held higher positions: three of the six inspectors commonly mentioned were Palestinians (D. Baramki, S.A.S. Husseini, and N. Makhouly) and a Palestinian (the Dimitri Baramki in the early 1930s. Source: self-taught scholar Stephan H. Private collection. Stephan) worked in the library.4 [ 78 ] Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham Baramki and Husseini became colleagues again in Libya in the mid 1960s; Makhouly’s 1941 Guide to Acre, published by the Department of Antiquities, still turns up at sites like the sole Palestinian-owned hotel in Acre; and Stephan H. Stephan’s work continues to be cited today, as for example, in Mahmoud Hawari’s essay on the Citadel of Jerusalem in this publication. But it was Dimitri Baramki (1909-1984), frequently called the first Palestinian archaeologist, who was the most productive, and the only one who pursued a lifelong career in the field. He began as a student inspector of antiquities during the British Mandate two months short of his eighteenth birthday, and achieved an internationally acknowledged standing as a UNESCO expert, Professor of Archaeology and Curator of the Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, and lecturer at the Lebanese University and the University of Balamand.