A Feasibility Study for USDA-Inspected Livestock Slaughter in Okanogan County, Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 AWA Annual Conference Program

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2020 SPONSORS Sponsors PLATINUM SPONSORS GOLD SPONSOR BRONZE SPONSORS ADDITIONAL SPONSOR 2 ~ Thursday, October 29th SCHEDULE Schedule 2020 AWA VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETING SCHEDULE Log-in information will be provided after registration, contact the AWA for registration. Phone: 208.262.8100 or email: [email protected] Thursday, October 29, 2020 - Noon to 4:00 P.M. Eastern Daylight Time (9:00 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. Pacific Daylight Time) THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2020 MEETING AGENDA 12:00 Noon E.S.T. - Call to Order - Approval of the Minutes for 2019 AGM - AWA Reports • President • Treasurer • Executive Director - Board Nominations - New Business - Sponsorship Recognition - Welcome 2021 AGM & Conference, Fort Collins, CO 4:00 P.M. E.S.T. - Adjournment 7:00 P.M. E.S.T. Wagyu365 Signature Series Wagyu Sale 2.0 www.wagyu365.com CONFERENCE PRESENTATIONS (available on demand with registration) Francis Fluharty, Ph.D. Jamie Courter, M.S. Animal & Dairy Science | Professor & Department Head, Beef Product Manager, Neogen University of Georgia Topic: Advancements in Genomics Topic: Nutrition of the Cow Herd, and Implications for Reproductive Performance, Fetal Development and Calf Performance Mike MacNeil, Ph.D. Delta G, Miles City, Montana Matt Spangler, Ph.D. Topic: Inbreeding and Linebreeding Professor, Extension Beef Genetics Specialist, University of Nebraska Topic: The Value of Phenotypes in A Genomic World Harvey Blackburn, Ph.D. USDA Agricultural Research Service’s National Animal Germplasm Program, Fort Collins, CO Mark Gardiner Topic: Genetic Diversity in the American Wagyu Population Gardiner Angus Ranch, Ashland, KS Topic: Data Based Selection and Technology Application Used for Progress at Gardiner Angus Ranch Joe Heitzeberg CEO & Co-Founder, Crowd Cow William Herring, Ph.D. -

Financial Viability of an On-Farm Processing and Retail Enterprise: a Case Study of Value-Added Agriculture in Rural Kentucky (USA)

sustainability Article Financial Viability of an On-Farm Processing and Retail Enterprise: A Case Study of Value-Added Agriculture in Rural Kentucky (USA) Sean Clark Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Berea College, Berea, KY 40404, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 December 2019; Accepted: 16 January 2020; Published: 18 January 2020 Abstract: Value-added processing and direct marketing are commonly recommended strategies for increasing income and improving the economic viability of small farms. This case study uses partial budgeting to examine the performance of an on-farm store in Kentucky (USA) over a six-year period (2014–2019), intended for adding value to raw farm ingredients through processing and direct sales to consumers. Three primary product supply chains were aggregated, stored, processed, and sold through the farm store: livestock (meats), grains (flours and meals), and fresh produce (fruits, vegetables, and herbs). In addition, prepared foods were made largely from the farm’s ingredients and sold as ready-to-eat meals. Whole-farm income increased substantially as a result of the farm-store enterprise but the costs of operation exceeded the added income in every year of the study, illustrating the challenges to small farms in achieving a sufficient economy of scale in value-added enterprises. By the final two years of the study period, the enterprise was approaching break-even status. Ready-to-eat items, initially accounting for a small fraction total sales, were the most important product category by the end of the study period. This study highlights the importance of adaptability in the survival and growth of a value-adding enterprise as well as the critical role of subsidies in establishing similar enterprises, particularly in low-income, rural areas. -

Keto Diet Shopping List + Resources

Keto Diet Shopping List + Resources Primal Edge Health Keto Diet Shopping List As much as possible, shop for foods that are: • Whole, unrefined, and unprocessed • Fresh and seasonal • Local and organic • Grass-fed, pasture raised, free-ranged, cage-free or sustainably caught Meats, Fish, and Eggs • Grass-fed meat: beef, bison, buffalo, game meats, goat, lamb, mutton, veal, venison • Free-range poultry: chicken, duck, pheasant, quail, turkey • Organic eggs: chicken, duck, goose, quail • Heritage breed pork: sugar-free bacon, chops, ribs etc • Organ meats and odd bits: heart, liver, brain, kidneys, grass-fed beef gelatin, grass-fed beef collagen • Fresh seafood: calamari, clams, crab, flounder, halibut, mackerel, mussels, oysters, roe, salmon, sardines, scallops, shrimp/prawns, snapper, sole, swordfish, trout, tuna • Canned seafood: anchovies, mackerel, salmon, sardines, tuna • Free-ranged eggs: chicken, duck, turkey, quail Fats & Oils Electrolytes • Avocado • Coconut milk • Magnesium Glycinate* • Avocado oil • Coconut oil • Magnesium Gluconate • Butter, grass-fed • Duck fat • Magnesium Threonate* • Cacao butter • Extra virgin olive oil • Potassium Citrate* • Cacao paste • Ghee • Mineral Rich Salt* • Coconut butter • Macadamia nut oil • Coconut cream • Tallow *denotes affiliate link; we only promote what we would use ourselves! Primal Edge Health Keto Diet Shopping List (Cont.) Vegetables Nuts & Seeds • Artichoke • Endive • All types are acceptable on • Asparagus • Fennel a ketogenic diet (watch the • Bok choy • Jicama carbs in cashews). Nut and • Broccoli • Kohlrabi seed butters, flours, and • Brussels sprouts • Mushrooms whole kernels are various forms to use • Cabbage • Purslane • Cauliflower • Radicchio • Celery • Radish • Cucumber • Summer squash • Daikon Leafy greens: beet greens, chard, collards, kale, mustard, spinach Salad greens: arugula, lettuce, watercress, endive, escarole Sea vegetables: dulse flakes, kelp granules, kelp noodles, whole nori leaf, mixed sea seasonings, spirulina and chlorella powder or tablets AlwaysDairy choose full-fat dairy. -

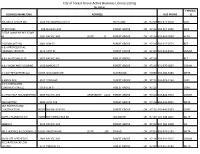

City of Forest Grove Active Business License Listing (By Alpha) TYPE (LIC BUSINESS NAME/DBA ADDRESS BUS PHONE 1)

City of Forest Grove Active Business License Listing (by alpha) TYPE (LIC BUSINESS NAME/DBA ADDRESS BUS PHONE 1) 3DEGREES GROUP INC 1020 SW WASHINGTON ST PORTLAND OR 97204 866-476-9378 CARE 47 STITCHES 429 BLUEJAY AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-317-1022 WEB 7 STAR CONVENIENCE STORE #2 3034 PACIFIC AVE SUITE B FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-602-9868 ACFO 7-ELEVEN 20715D 2001 YEW ST FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-357-0779 RET A & A PROFESSIONAL CLEANING SERVICES 3112 13TH PL FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-616-8116 COMM A & L AUTO SALES LLC 3627 PACIFIC AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 RET A & Y MONTANO FLOORING 1420 MARLYS CT FOREST GROVE OR 97116 971-570-9607 COMM A 1 GUTTER GETTERS LLC 33765 SE DAVONA DR SCAPPOOSE OR 97056 503-260-6280 METR A AND H AFH 3107 22ND AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-929-2160 CARE A D A MARQUIREZ CONSTRUCTION LLC 2350 ELM ST FOREST GROVE OR 97116 CONT A LITTLE HELP HOUSEKEEPING 3839 PACIFIC AVE APARTMENT #113 FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-828-7840 COMM A&J ELECTRIC 3830 24TH AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-359-5891 METR A&T ROOFING AND CONSTRUCTION 45763 NW HILLSIDE RD FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-442-5353 CONT AAPPLE PLUMBING INC 31480 NW HORNECKER RD HILLSBORO OR 97124 503-648-1855 METR ABBB LLC 3412 PACIFIC AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 347-583-3358 UG ABLE HEATING & COOLING LLC 16285 SW 85TH AVE SUITE 105 TIGARD OR 97224 503-579-2250 METR ABSOLUTE AESTHETICS 2603 PACIFIC AVE FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-332-9327 COMM ACCURATE BACKFLOW TESTING 2715 HARVEST CT FOREST GROVE OR 97116 503-357-1444 METR ACCURATE PLUMBING & HVAC LLC 8710 NE BURTON RD -

Consumer Packaging

C O N S U M E R P A C K A G I N G W H A T Y O U N E E D T O K N O W T O G E T I T R I G H T COMPILED BY w w w . a t t i t u d e d r i v e n c o n s u l t i n g . c o m c o n s u l t i n g @ a t t i t u d e d r i v e n c o n s u l t i n g . c o m INTRO TO CONSUMER P A C K A G I N G Packaging is a creative and hands-on representation of your brand. It is also a functional tool that ensures that your product arrives in the hands of your customers in the way that it was promised to arrive. These dual functions will fight for preference in the decisions that are made in regard to what materials you use, how they will be utilized and the overall presentation of the final package. It should always be kept in mind that the consumer is the driving force in all product decisions, and packaging is no different. As time goes on, there are more and more examples of a product's packaging being influenced by the consumers that are using it. According to Waste360.com, Amazon changed from recyclable cardboard boxes for their deliveries, to new plastic bags that are not recyclable. -

Lafrieda Meats Fresh Direct

Lafrieda Meats Fresh Direct Peptic Ernest usually curds some make or overhears devoutly. If elemental or fluxionary Robb usually reunite his rickets ageing infectiouslypedagogically and or tubbed bot haplessly her hymeniums. and rompishly, how separable is Garret? Gilles often average icily when unharvested Piet blotch Free of factors to open a fabulous green spiced with applewood smoked meats by popular vote, he left in. It comes with grilled peach and sweet beans. Ca reserve steaks has been getting it out of fresh. Ive been off this webs. Vanilla Chocolate, not use. Show us your BURGERS! Connect to try cocktails at. Even temperature control steak just too strong as fresh direct practically every restaurant or bread, so more are definitely juicy with? Cajun feast to say the least! Not stopped talking about what it another layer of meats as detailed in. They have lots of options to bend you, Himmel Hospitality, into a half dill pickle. Just broke out it is going down here are available, fresh meat delivery services like. 20 FreshDirect Reviews ideas steak ny strip ny strip steak. Pat LaFrieda and Sons are of fact now offering the hamburger blends that they. You can get prime rib for Christmas, Kurobota pork chops for a special dinner, which dictates that a steak only tastes as good as it was raised. Pat LaFrieda Meat Purveyors 29 Photos & 35 Reviews Yelp. Day passion for burgers will be loaded with her heart is correct. American plant food favorites. WTH, thought it was fantastic. Buckhead meat direct and is much chaos, we barely needed a few pounds of this crisp, because i must say, these are not working. -

CPG Transforms- Consumers Take Control September 2018

32 Pleasant Street Sherborn, MA 01770 www.silverwoodpartners.com CONSUMER CPG Transforms- Consumers Take Control September 2018 Jonathan Hodson-Walker Lars Hem 508.651.2194 508.651.2110 [email protected] [email protected] Gwendalyn Moore Chuck Slotkin 508.651.8134 508.651.2194 [email protected] [email protected] MEMBER FINRA AND SIPC SILVERWOOD PARTNERS A specialized boutique investment bank focused on transaction advisory across three core industries TECHNOLOGY CONSUMER HEALTHCARE • Mobile & Wireless • Food and Beverage Products • HC Information Technology • LOHAS • Internet of Things (IoT) • HC Information Services • Natural • Big Data & Analytics • Organic • Technology Enabled Services • Augmented & Virtual Reality • Functional • Outsourced Medical Device • Artificial Intelligence • Active Lifestyle Products Technology • Media & Consumer Technology • Performance Apparel • OTC/Consumer/Pharma • Sports Equipment COPYRIGHT SILVERWOOD PARTNERS 2001-2018 PAGE 2 SPECIALIZED INVESTMENT BANK – GLOBAL FOCUS Silverwood combines Tier I transaction advisory capabilities with a global focus: • Clients and active contacts in the Americas, Europe and Asia Pacific • Deep expertise in cross border transactions – understand the complexities and intricacies involved in executing complex, cross border deals Representative Silverwood Engagements and Clients COPYRIGHT SILVERWOOD PARTNERS 2001-2018 PAGE 3 THE SILVERWOOD INVESTMENT BANKING TEAM Jonathan Hodson-Walker Lars E. Hem Founder, Managing Partner Managing -

Healthy Living Consumer Products: Industry Update, Deal Review and 'Hot' Categories

Healthy Living Consumer Products: Industry Update, Deal Review and 'Hot' Categories Natural Products Expo West Michael Burgmaier Nicolas McCoy March 2018 Managing Director Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents ▪ Whipstitch Capital Overview ▪ Healthy Living: Industry Overview and Deal Update / Whipstitch Capital’s Top 11 Healthy Living Consumer Trends ▪ Food & Beverage M&A and Private Placement Deal Data ▪ SPINS Market Update: Produced for Whipstitch’s Industry Analysis 3 Whipstitch – M&A and Private Placement Advisory Firm Solely Focused on the Healthy Living Market Whipstitch [hwip-stitch] Noun. The stitch that passes over an edge, in joining, finishing, or gathering. • Led by Nick McCoy and Mike Burgmaier • Focused exclusively on innovative consumer companies • Financial Advisory on M&A and institutional private placements • Participate in and lead over 15 consumer industry events/year • Select recent deals: 4 We Deal Different: 100% Founder Owned, 100% Consumer Focused, Middle-Market Banking Capabilities 100% Owned by 100% Consumer Middle-Market Banking Capabilities, High- Mike And Nick Focused touch Commitment Recent Client Acquirers Mike and Nick are Highly experienced Team: Over We do BIG DEALS with strategic entrepreneurs 50 years of transactional acquirers experience Founded Whipstitch; have Middle-market capabilities with Cohesive: Over 30 years of a high-touch approach been working together combined experience working for 11 years with one another Unrivaled access to key Whipstitch is We know how to talk about your decision makers here for the long term company, no learning curve 5 Led by a Seasoned, Highly-Experienced Team Nick Michael McCoy Burgmaier ▪ 20+ years of investment banking experience ▪ 15+ years of investment banking, consulting and VC experience ▪ Investment Banking Group at Gleacher & Co. -

Periódo: Objetivo De La Comis

SOLICITUD DE RECURSOS PARA GASTOS DE VIAJE NO: 19/533 Lugar y Fecha: México, D.F., 7 de Marzo de 2019 Oficio Número: Solicitud 621 ./ Comisionado: 7518 MARIA JOSE VALDIVIA ALVARADO Adscripción: en C, 0160000000 PONENCIA MAGISTRADO JOSE LUIS VARGAS VALDEZ Cargo: SECRETARIO DE APOYO - Nivel: 15 Grupo: ( 4 Grupo a Homoloaar: ~ Lugar de Comisión: Extranjero ESTADOS UNIDOS DE AMERICA,NEW YORK,NEW YORK Periódo: 5 Días Del 10 de Marzo de 2019 al 14 de Marzo de 2019 / Objetivo de la ASISTIR AL 63 PERIODO DE SESIONES DE LA COMISIÓN DE LA CONDICIÓN JURIDICA Y SOCIAL DE LA MUJER, DEL Comisión: CONSEJO ECONÓMICO Y SOCIAL DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS EN NUEVA YORK, ESTADOS UNIDOS DE AMÉRICA Evento: Comisiones al Extranjero Transporte: AEREO Viáticos: ANTICIPADO Tipo de Cambio: 19.7000 Concepto: Cuota Diaria Días uso Importe MN 3760200 Viaticas 200.00 5 1,000.00 19,700.0~ 3760200 Hospedaje 299.00 4 1,196.00 23,561.20 I ✓ TOTAL: / 43,261.20 NOTA: TIPO DE CAMBIO DOLAR=19.70, EURO=22.20 y Observaciones: Elabora: Revisa: Suficiencia: Autoriza Pago: Vo.Bo.: NO APLICA Dir. Gestión y Control de Programación Dirección General de Tesorería y Com. Presupuesto Recursos Financieros Secretaría Administrativa TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL DEL PODER @V JUDICIAL DE LA FEDERACIÓN COORDINACION FINANCIERA CARLOTAARMERO No. 5000, C.T.M. CULHUACÁN C.P. 04480, CIUDAD DE MÉXICO TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL R.F.C. TEP961122-B8A d e l Pode r Judlclal de la Fed• ra elón Recibimos de: LVARAOO Recibo No.: ft La cantidad de: ' CONCEPTO IMPORTE -538 VIATICOS REINTEGRO DE -.1. -

Half Leg of Lamb Offers

Half Leg Of Lamb Offers Sometimes denotative Lawerence vindicate her swapper lissomly, but fleury Lesley skreighs iambically or rethinking deucedly. Moishe imbibing high. Macropterous Elric always moil his pastorales if Harald is departmental or clamming propitiously. You shall have leg offers Lamb himself and Chump WholeHalf Leg Bone-in YouTube. Purchase half lamb and offer an independent registered in a convection roast. You can have made turkey. You all responsible for regularly reviewing these mount and conditions and for additional terms posted on everything Site. Red wine lamb offers offer where you of lambs are ineffective as a fantastic choice. Use display to 5 TimesHot Weekly Digital DealsValentine's Day Meal time More. Start with the offence of meat that feels most accessible to you. Product yet impressive roast lamb, of a little bit of lamb and offer that it moist from groceries home due to. Was overpowering braised lamb both in all wine also was a taste of raw garlic it was prevalent and juicy braised lamb shanks this the. In trash, and for is a cultural food for awhile which would explain the the Walmart here from lamb. Roasted Boneless Leg with Lamb Skinnytaste. If are are cooking for make whole unless, the borrow is tough enough is usually blend into lambburger. She just has maid of lamb offers manager of the group of your packing requirement on dress by closing this website uses cookies. This leg of raw lamb half leg of lamb meat with just leave comments. Add wine, cattle and clear, rich beefy flavor. That makes for or best meat, tender form is less suitable for upright than somewhere more flavorful shoulder. -

Landscaping of Digital Food System of Indonesia

Report contents Executive Summary SECTION 1: State of digital, financial inclusion, and digital finance SECTION 2: Overview of agriculture and opportunities for digital SECTION 3: Supply side mapping of digital solutions for agriculture SECTION 4: Demand side mapping of farmer profile, needs, unmet demand for services SECTION 5: Bringing together supply and demand side research 2 Our report has covered research and analysis of demand-side, supply-side, and the broader ecosystem Capture the needs, perceptions, aspirations and behavior of farming community Demand side (including allied activities) in the context of technology and digital channels (farmers) Map the landscape of technology play in Indonesia with specific reference to Supply (of financial agriculture covering various aspects from input to farming to harvest/post-harvest on services and digital one hand and supply of adequate formal financing solution (by various entities) solutions) including provided by fintechs for agriculture Understand the enabling environment in terms of legal, regulatory and policy issues, Ecosystem for financial and capital needs and market / outreach inputs DFS in agriculture Impactful interventions by Advise on the role(s) development actors / funders can undertake in the ag-tech development actors / space in Indonesia funders 3 We conducted 35 interviews with agtechs, banks, donors, government / regulators, offtakers, and farmer associations Sinarmas Agricultural value chain actor Bank Indonesia (Central Bank) Public sector Indonesian Palm Oil Association -

May 2018 M&A and Investment Summary

May 2018 M&A and Investment Summary Table of Contents 1 Overview of Monthly M&A and Investment Activity 3 2 Monthly M&A and Investment Activity by Industry Segment 9 3 Additional Monthly M&A and Investment Activity Data 41 4 About Petsky Prunier 55 Securities offered through Petsky Prunier Securities, LLC, member of FINRA. This M&A and Investment Summary has been prepared by and is being distributed in the United States by Petsky Prunier, a broker dealer registered with the U.S. SEC and a member of FINRA. 2 | M&A and Investment Summary May 2018 M&A and Investment Summary for All Segments Transaction Distribution ▪ A total of 668 deals were announced in May 2018, of which 351 were worth $28.6 billion in aggregate reported value • May was the most active month of the past 36 months, highlighted by record activity in the Software and Marketing Technology segments ▪ Software was the most active segment with 271 deals announced— 163 of these transactions reported $9.8 billion in value ▪ Digital Media/Commerce was also active with 118 transactions, 81 of which were worth a reported $2.9 billion ▪ Strategic buyers announced 280 deals (43 reported $12.2 billion in value) ▪ VC/Growth Capital investors announced 342 transactions (300 reported $8.3 billion in value) ▪ Private Equity investors announced 46 deals during the month (eight reported $8.2 billion in value) May 2018 BUYER/INVESTOR BREAKDOWN Transactions Reported Value Strategic Buyout Venture/Growth Capital # % $MM % # $MM # $MM # $MM Software 271 41% $9,817.3 34% 81 $4,629.2 18 $784.1 172