Annex 4. Overview of Jakarta's Drainage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks Journeys Through Java; Topographical Data from an Old Sundanese Source

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks journeys through Java; topographical data from an old Sundanese source In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 138 (1982), no: 4, Leiden, 413-442 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 08:23:09PM via free access J. NOORDUYN BUJANGGA MANIK'S JOURNEYS THROUGH JAVA: TOPOGRAPHICAL DATA FROM AN OLD SUNDANESE SOURCE One of the precious remnants of Old Sundanese literature is the story of Bujangga Manik as it is told in octosyllabic lines — the metrical form of Old Sundanese narrative poetry — in a palm-leaf MS kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford since 1627 or 1629 (MS Jav. b. 3 (R), cf. Noorduyn 1968:460, Ricklefs/Voorhoeve 1977:181). The hero of the story is a Hindu-Sundanese hermit, who, though a prince (tohaari) at the court of Pakuan (which was located near present-day Bogor in western Java), preferred to live the life of a man of religion. As a hermit he made two journeys from Pakuan to central and eastern Java and back, the second including a visit to Bali, and after his return lived in various places in the Sundanese area until the end of his life. A considerable part of the text is devoted to a detailed description of the first and the last stretch of the first journey, i.e. from Pakuan to Brëbës and from Kalapa (now: Jakarta) to Pakuan (about 125 lines out of the total of 1641 lines of the incomplete MS), and to the whole of the second journey (about 550 lines). -

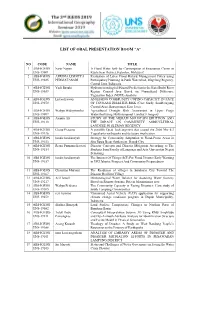

List of Oral Presentation and Round Table

LIST OF ORAL PRESENTATION ROOM “A” NO CODE NAME TITLE 1 ABS-IGEOS Nasir Nayan Is Flood Water Safe for Consumption at Evacuation Center in UNS-19001 Kuala Krai District, Kelantan, Malaysia? 2 ABS-IGEOS AFRINIA LISDITYA Evaluation of Lahar Flood Hazard Management Policy using UNS-19035 PERMATASARI Participatory Planning in Putih Watershed, Magelang Regency, Central Java, Indonesia 3 ABS-IGEOS Yudi Basuki Hydrometeorological Hazard Prediction in the Kuto Bodri River UNS-19039 Region Central Java Based on Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) Analysis 4 ABS-IGEOS Listyo Irawan ASSESSING COMMUNITY COPING CAPACITY IN FACE UNS-19070 OF TSUNAMI DISASTER RISK (Case Study: Sumberagung Coastal Area, Banyuwangi, East Java) 5 ABS-IGEOS Wahyu Widiyatmoko Agricultural Drought Risk Assessment in Upper Progo UNS-19097 Watershed using Multi-temporal Landsat 8 Imagery 6 ABS-IGEOS Ananto Aji STUDY OF THE MERAPI MOUNTAIN ERUPTION AND UNS-19110 THE IMPACT ON COMMUNITY AGRICULTURAL LANDUSE IN SLEMAN REGENCY 7 ABS-IGEOS Cecep Pratama A possible Opak fault segment that caused the 2006 Mw 6.3 UNS-19126 Yogyakarta earthquake and its future implication 8 ABS-IGEOS herdis herdiansyah Strategy for Community Adaptation to Flood-Prone Areas in UNS-19153 Situ Rawa Besar Settlement, Depok City 9 ABS-IGEOS Retno Purnama Irawati Disaster Concepts and Disaster Mitigation According to The UNS-19154 Students from Faculty of Language and Arts, Universitas Negeri Semarang 10 ABS-IGEOS herdis herdiansyah The Internet Of Things (IoT) For Flood Disaster Early Warning UNS-19157 -

USAID Mitra Kunci Initiative

USAID Mitra Kunci Initiative Quarterly Report (October – December 2018) (Q1/FY2019) Task Order No. AID-497-TO-17-00001, under Youth Power: Implementation IDIQ Contract AID-OAA-I-15-00014 January 15, 2019 This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of DAI Global, LLC and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. i USAID Mitra Kunci Initiative Quarterly Report (October – December 2018) Project Title: USAID Mitra Kunci Initiative Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Indonesia Task Order Number: AID-497-TO-17-00001, under Youth Power IDIQ Contract AID-OAA-I-15-00014 COR: Ms. Mimy Santika Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Status: Final submission Date of Publication: January 29, 2019 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. The information and data contained herein are protected from disclosure by 18 U.S.C. § 1905 and are proprietary information as defined by 41 U.S.C. § 423. They shall not be disclosed in whole or in part for any purpose to anyone by the government, except for purposes of proposal evaluation, negotiation, and contract award, as provided by FAR 15.413-1 and FAR 3.104, or to the public, without the express written permission of DAI Global, LLC. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................ -

Indonesia's Transition to a Green Economy: a Stocktaking Report, 2019

INDONESIA’S TRANSITION TO A GREEN ECONOMY – A STOCKTAKING REPORT 2 Copyright © United Nations Development Programme, 2019 The report is published as part of the Partnership for Action on Green Economy (PAGE) – an initiative by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNDP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Development Programme. Citation PAGE (2019), Indonesia’s Transition to a Green Economy: A Stocktaking Report Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Development Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Development Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. STOCKTAKING REPORT 2019 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was commissioned by the Partnership for Action on Green Economy (PAGE) Indonesia under UNDP Indonesia Country Office as PAGE Indonesia appointed lead agency. -

Annual State of Environmental Report (Aser) 2007 Tangerang Municipality

ANNUAL STATE OF ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT (ASER) 2007 TANGERANG MUNICIPALITY THE GOVERNMENT OF TANGERANG CITY BANTEN PROVINCE ANNUAL STATE OF ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT (ASER) 2007 TANGERANG MUNICIPALITY THE GOVERNMENT OF TANGERANG CITY BANTEN PROVINCE F O R E W O R D Assalamuala’ikum Wr. Wb. Praise and thanks we give to Allah SWT that because of His blessings the Government of Tangerang City can compose the Annual State of Ennvironmental Report (ASER) 2007 Tangerang Municipality Book. The Annual State of Ennvironmental Report (ASER) 2007 Tangerang Municipality is a report on the environmental condition and quality for Tangerang City area and is intended to provide information needed in making decisions, regulations or program interventions that are rational, holistic and integrated. The composing of this book is one of the effort in implementing Regulation No. 23 year 1999 regarding Envi- ronmental Management which stated that ”In order to manage the environment, the government is obligated to provide: environmental information and inform the people”. Hopefully what we have done will have a big impact on environmental management efforts in Tangerang City and in turn can benefit future generations. May Allah SWT always grant us with His blessings. Amen. Wassalamuala’ikum Wr. Wb. Tangerang, MAJOR OF TANGERANG H. WAHIDIN HALIM ANNUAL STATE OF ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT (ASER) TANGERANG MUNICIPALITY 2007 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Annual State of Environmental Report (ASER) 2007 Tangerang Municipality is an executive summary re- port on environmental condition in Tangerang City. This report is intended to encourage environmental aware- ness in various stakeholders towars clean, prosperous, and sustainable environment of Tangerang City. We realize that there are still many uncovered environmental situations and problem in the city that we have not presented here due to our limitations. -

2018B Indonesia Mercury Country Situation

Mercury Country Situation Report Indonesia June 2018 i Regional Hub Southeast Asia and East Asia Name and address of BaliFokus Foundation the NGO Mandalawangi No. 5 Jalan Tukad Tegalwangi, Sesetan Denpasar 80223, Bali Indonesia Contact person and Yuyun Ismawati, [email protected] email Date 29 June 2018 Country and region Indonesia, Southeast Asia Title of project Mercury Country Situation Report - Indonesia Acknowledgment We take this opportunity to thank all those who were instrumental in compiling and contributing this report. This report presents updates on mercury situation in Indonesia. The report also recommends action steps by different stakeholders to protect the community from exposure to mercury. This report is prepared by: Yuyun Ismawati Krishna Zaki Mochammad Adi Septiono With contributions from: Margaretha Quina - ICEL Mutiara Nurzahra - ICEL Tommy Apriando - Mongabay ii List of Abbreviation ASGM Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining APRI Asosiasi Petambang Rakyat Indonesia (Association of Indonesian Community Miners) BPPT Badan Pengkajian dan Penerapan Teknologi / Agency for Technology Assessment and Application ESDM Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral IPR Izin Pertambangan Rakyat IUP Izin Usaha Pertambangan/Mining Lisence KLHK Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (Ministry of Environment and Forestry) MA Mahkamah Agung PESK Pertambangan Emas Skala Kecil (ASGM) Perpres Peraturan President (Presidential Decree) WPR Wilayah Pertambangan Rakyat WHO World Health Organisation iii Table of Content Acknowledgment ii List of abbreviation iii Table of Content iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Regulations related to mercury and cinnabar 4 3. mercury inventory assessment 6 4. Mercury Supply, Availability, and Trade 10 5. Mercury-added Products 15 6. Mercury emissions and releases 18 7. -

Jurnal Buana Jurusan Geografi Fakultas Ilmu Sosial – Unp E-Issn : 2615 – 2630 Vol- 4 No- 5 2020

JURNAL BUANA JURUSAN GEOGRAFI FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL – UNP E-ISSN : 2615 – 2630 VOL- 4 NO- 5 2020 MORFOLOGI ALLUVIAL PLAIN DESA BUMIWANGI KECAMATAN CIPARAY Aditya Al-Fikri Amanullah1*,Andiko Putra1,Agung Aprillian1, Afrillia Tri Cahyani1Chriswanti Pangestu1,Elfi Effendi1,Fernando Hero Alyandri1,Geny Handani Putra1,Syafrina1,Verdi Jainathul Khamsya1, Risky Ramadhan2 1 MahasiswaJurusan Geografi, FakultasIlmu Sosial, UniversitasNegeri Padang 2 Dosen Jurusan Geografi, FakultasIlmu Sosial, UniversitasNegeri Padang [email protected] ABSTRAK Bandung Selatan adalah salah satu daerah yang termasuk kedalam Cekungan Bandung yang merupakan wilayah pegunungan.Gunungapi yang aktif maupun non aktif berderet di daerah ini, di antaranya Gn. Patuha, Gn. Wayang, dan Gn. Windu.Karena hal tersebut Bandung Selatan memiliki potensi sumber daya alam yang melimpah, diantaranya sumber daya air, panasbumi, dan pertambangan.Sumber air berderet di sepanjang lereng utara dari gunung-gunung tersebut.Cisanti yang berada di kaki Gunung Wayang merupakan hulu Sungai Citarum yang menjadi sungai terpanjang di Jawa Barat. Kata kunci:Bandung Selatan; Cekungan Bandung; Sungai Citarum ABSTRACT South Bandung is one of the areas included in the Bandung Basin which is a mountainous region. Active and non-active volcanoes line up in this area, including Mt. Patuha, Mt. Puppet, and Mt. Windu Because of this South Bandung has abundant natural resource potential, including water resources, geothermal resources, and mining. Water sources lined up along the northern slopes of the mountains. Cisanti at the foot of Mount Wayang is the headwaters of the Citarum River which is the longest river in West Java. Keywords: South Bandung; Bandung Basin; Citarum River Pendahuluan diidentikkan sebagai salah satu pusat Tanah Sunda atau yang dikenal bencana. -

Systematicreview81food.Pdf

< OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN BiaOPv HFC 161996 NO. VOLS. 3ARD ECONOMY THESIS LEAF ATTACH. I THIS TITLE D ECONOMY AUTH. 1ST D ~ OR TITLE I.D. COLOR 20706 ^ffiT^W IS ISSN. BIX 3 - SYSID S^NCY*"* -BL- EW SERIES Systematic Review of Southeast Asian Longtail M&cm Macaca fascicular™ (Raffles, [11 590 . 5 Confabs :d for puti FIELDIANA Zoology NEW SERIES, NO. 81 Systematic Review of Southeast Asian Longtail Macaques, Macaca fascicularis (Raffles, [1821]) Jack Fooden Research Associate Division of Mammals Department of Zoology Field Museum of Natural History Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496 Accepted January 13, 1995 Published November 30, 1995 Publication 1470 PUBLISHED BY FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY © 1995 Field Museum of Natural History Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-61092 ISSN 0015-0754 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Table of Contents Subspecies Accounts 70 Macaca fascicularis fascicularis (Raffles, [1821]) 70 Abstract 1 Macaca fascicularis aurea I. Geoffroy, Introduction 1 [1831] 77 Geographic Distribution 2 Macaca fascicularis philippinensis I. Pelage 3 Geoffroy, [1843] 79 General Characterization 3 Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, Sex and Age Variation 11 1902b 79 Geographic Variation 11 Macaca fascicularis fusca Miller, Dorsal Pelage Color Saturation 11 1903a 81 Dorsal Pelage Erythrism 13 Macaca fascicularis lasiae (Lyon, Crown Color 15 1916) 81 Lateral Facial Crest Pattern 18 Macaca fascicularis atriceps Kloss, External Measurements and Propor- 1919c 82 tions 21 Macaca fascicularis condorensis Kloss, Sex and Age Variation 21 1926 84 Geographic Variation 22 Macaca fascicularis tua Kellogg, Head and Body Length 22 1944 86 Tail Length 23 Macaca fascicularis karimondjawae Cranial Characters 30 Sody, 1949 86 Sex and Age Variation 30 Macaca fascicularis subspecies undeter- Geographic Variation 33 mined 87 Molecular Biology and Genetics 35 Evolution and Dispersal 87 > Mitochondrial DNA 35 Stage I, 1 Ma 88 Nuclear DNA 39 Stage II, ca. -

Trend and Condition of the Jakarta Bay Ecosystem

LOCAL MILLENIUM ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT: CONDITION AND TREND OF THE GREATER JAKARTA BAY ECOSYSTEM Report Submitted to Assistant Deputy for Coastal and Marine Ecosystem The Ministry of Environment, Republic of Indonesia Prepared by Zainal Arifin Research Centre for Oceanography - LIPI The Ministry of Environment, Republic of Indonesia Jakarta 2004 Acknowledgements This report is a result of local millennium assessment with a case study of Greater Jakarta Bay Ecosystem (GJBE). This exercise is mainly based on secondary data provided by several stakeholders in GJBE area. I personally would like to thank all colleagues who directly or indirectly assist in the preparation of the document. Special thank to the Ministry of Environment, in particular to Mr. Effendy Sumardja (National Focal Point of GEF Indonesia), Mr. Sudariyono (Deputy for Environmental Conservation), and Mr. Heru Waluyo (Assistant for Coastal and Marine Ecosystem) for allowing me to participate in this exercise. My sincerely thanks also go to Ms. Liliek Litasari and Ms. Wahyuni of Dinas Peternakan, Perikanan dan Kelautan DKI, Mr. Bayu of LPP Mangrove, and Mr. Onrizal of Faculty of Forestry – IPB. Jakarta, April 18, 2004 Zainal Arifin ii TABLE OF CONTENT I BACKGROUND 1 II CONDITION AND TREND OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES 3 2.1. Major types of sub-system 3 2.2. Greater Jakarta Bay Ecosystem Services 7 III DRIVERS OF ECOSYSTEM CHANGE 12 3.1. Indirect Drivers of Change 13 3.2. Direct Drivers of Change 18 IV INDICATORS OF CONDITION OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES 21 4.1. Marine Production 21 4.2. Access to Clean Water 21 4.3. Income and Education Levels 21 V MANAGEMENT INTERVENTIONS 23 REFERENCES iii I. -

GROWING FAST to BE the BEST Berkembang Pesat Untuk Menjadi Yang Terbaik Laporan Tahunan 2015 Annual Report

PT MNC LAND Tbk Laporan Tahunan 2015 Annual Report PT MNC LAND Tbk PT MNC LAND Tbk GROWING FAST MNC Tower 17th Floor Jl. Kebon Sirih No. 17-19 Jakarta 10340 Indonesia TO BE THE BEST T : +62 21 392 9828 F : +62 21 392 1227 Berkembang Pesat www.mncland.com Untuk Menjadi yang Terbaik GROWING FAST TO BE THE BEST THE BE TO FAST GROWING Berkembang Pesat Untuk Menjadi yang Terbaik Berkembang Pesat Untuk Menjadi Laporan Tahunan Laporan 2015 Annual Report Laporan Tahunan 2015 Annual Report GROWING FAST TO BE THE BEST Berkembang Pesat Untuk Menjadi yang Terbaik Perseroan berupaya untuk menjadi pemain terdepan dalam industri properti seiring dengan pertumbuhan industri properti di Indonesia. Pertumbuhan ini mendorong pasar properti menjadi semakin kompetitif, sehingga Perseroan memantapkan langkahnya untuk selalu menghasilkan kinerja yang lebih baik, kualitas properti yang lebih memberikan daya tarik tersendiri, serta mendukung perkembangan infrastruktur dan perekonomian negara melalui portofolio propertinya. Perseroan senantiasa berupaya untuk bertumbuh secara pesat untuk menjadi pemain terbaik di bidangnya. The Company strives to be the leading player in the property industry in line with the property industry growth in Indonesia. This growth encourages the property market to become increasingly competitive so that the Company establishes its pace to always produce better performance, properties with their own attractive qualities, as well as supporting the development of the infrastructure and economy of the country through its property portfolio.