Medicinal Plant Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Assessment of Ephedra Species (Ephedra Spp.)

Annex 3 Ref. Ares(2010)892815 – 02/12/2010 Recognising risks – Protecting Health Federal Institute for Risk Assessment Annex 2 to 5-3539-02-5591315 Scientific assessment of Ephedra species (Ephedra spp.) Purpose of assessment The Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL), in collaboration with the ALS working party on dietary foods, nutrition and classification issues, has compiled a hit list of 10 substances, the consumption of which may pose a health risk. These plants, which include Ephedra species (Ephedra L.) and preparations made from them, contain substances with a strong pharmacological and/or psychoactive effect. The Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection has already asked the EU Commission to start the procedure under Article 8 of Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 for these plants and preparations, for the purpose of including them in one of the three lists in Annex III. The assessment applies to ephedra alkaloid-containing ephedra haulm. The risk assessment of the plants was carried out on the basis of the Guidance on Safety Assessment of botanicals and botanical preparations intended for use as ingredients in food supplements published by the EFSA1 and the BfR guidelines on health assessments2. Result We know that ingestion of ephedra alkaloid-containing Ephedra haulm represents a risk from medicinal use in the USA and from the fact that it has now been banned as a food supplement in the USA. Serious unwanted and sometimes life-threatening side effects are associated with the ingestion of food supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. Due to the risks described, we would recommend that ephedra alkaloid-containing Ephedra haulm be classified in List A of Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006. -

The Effect of Cultivation and Plant Age on the Pharmacological Activity of Merwilla Natalensis Bulbs

South African Journal of Botany 2005, 71(2): 191–196 Copyright © NISC Pty Ltd Printed in South Africa — All rights reserved SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY ISSN 1727–9321 The effect of cultivation and plant age on the pharmacological activity of Merwilla natalensis bulbs SG Sparg, AK Jäger and J van Staden* Research Centre for Plant Growth and Development, University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg, Private Bag X01, Scottsville 3209, South Africa * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 5 March 2004, accepted in revised form 27 August 2004 Merwilla natalensis bulbs were cultivated at two thesis by COX-1, with activity decreasing as the bulbs different sites under different treatments. Bulbs were matured. The cultivation treatments had a significant harvested every six months for a period of two years effect on the antihelmintic activity of bulbs cultivated at and were tested for antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and the Fort Hare site. Results suggest that irrigation might anthelmintic activity. The cultivation treatments had no increase the antihelmintic activity of the bulbs if culti- significant effect (P ≤ 0.05) on neither the antibacterial vated in areas of low rainfall. The age of the bulbs at activity, nor the anti-inflammatory activity. However, the both sites had a significant effect on the antihelmintic age of the bulbs had a significant effect against the test activity, with activity increasing with plant maturity. bacteria and on the inhibition of prostaglandin syn- Introduction Merwilla natalensis (Planchon) Speta (synonym Scilla varied when the plants were grown in different geographical natalensis) is ranked as one of the more commonly-sold regions. -

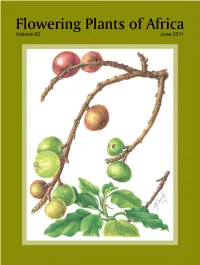

Albuca Spiralis

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

Asparagaceae Subfam. Scilloideae) with Comments on Contrasting Taxonomic Treatments

Phytotaxa 397 (4): 291–299 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.397.4.3 New combinations in the tribe Urgineeae (Asparagaceae subfam. Scilloideae) with comments on contrasting taxonomic treatments MARIO MARTÍNEZ-AZORÍN1*, MANUEL B. CRESPO1, MARÍA Á. ALONSO-VARGAS1, ANTHONY P. DOLD2, NEIL R. CROUCH3,4, MARTIN PFOSSER5, LADISLAV MUCINA6,7, MICHAEL PINTER8 & WOLFGANG WETSCHNIG8 1Depto. de Ciencias Ambientales y Recursos Naturales (dCARN), Universidad de Alicante, P. O. Box 99, E-03080 Alicante, Spain; e- mail: [email protected] 2Selmar Schonland Herbarium, Department of Botany, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa 3Biodiversity Research, Assessment & Monitoring, South African National Biodiversity Institute, P.O. Box 52099, Berea Road 4007, South Africa 4School of Chemistry and Physics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 4041 South Africa 5Biocenter Linz, J.-W.-Klein-Str. 73, A-4040 Linz, Austria 6Iluka Chair in Vegetation Science & Biogeography, Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University, Murdoch WA 6150, Perth, Australia 7Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, Stellenbosch, South Africa 8Institute of Biology, Division Plant Science, NAWI Graz, Karl-Franzens University Graz, Holteigasse 6, A-8010 Graz, Austria *author for correspondence Abstract As part of a taxonomic revision of tribe Urgineeae, and informed by morphological and phylogenetic evidence obtained in the last decade, we present 17 new combinations in Austronea, Indurgia, Schizobasis, Tenicroa, Thuranthos, Urgineopsis, and Vera-duthiea. These are for taxa recently described in Drimia sensu latissimo or otherwise named during the past cen- tury. -

Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase-Inhibitory Properties of Long-Term Stored Medicinal Plants Stephen O Amoo, Adeyemi O Aremu, Mack Moyo and Johannes Van Staden*

Amoo et al. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012, 12:87 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/12/87 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase-inhibitory properties of long-term stored medicinal plants Stephen O Amoo, Adeyemi O Aremu, Mack Moyo and Johannes Van Staden* Abstract Background: Medicinal plants are possible sources for future novel antioxidant compounds in food and pharmaceutical formulations. Recent attention on medicinal plants emanates from their long historical utilisation in folk medicine as well as their prophylactic properties. However, there is a dearth of scientific data on the efficacy and stability of the bioactive chemical constituents in medicinal plants after prolonged storage. This is a frequent problem in African Traditional Medicine. Methods: The phytochemical, antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase-inhibitory properties of 21 medicinal plants were evaluated after long-term storage of 12 or 16 years using standard in vitro methods in comparison to freshly harvested materials. Results: The total phenolic content of Artemisia afra, Clausena anisata, Cussonia spicata, Leonotis intermedia and Spirostachys africana were significantly higher in stored compared to fresh materials. The flavonoid content were also significantly higher in stored A. afra, C. anisata, C. spicata, L. intermedia, Olea europea and Tetradenia riparia materials. With the exception of Ekebergia capensis and L. intermedia, there were no significant differences between the antioxidant activities of stored and fresh plant materials as measured in the β-carotene-linoleic acid model system. Similarly, the EC50 values based on the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay were generally lower for stored than fresh material. Percentage inhibition of acetylcholinesterase was generally similar for both stored and fresh plant material. -

Scilla Hakkariensis, Sp. Nov. (Asparagaceae: Scilloideae): a New Species of Scilla L

adansonia 2020 ● 42 ● 2 DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Bruno David Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Thierry Deroin RÉDACTEURS / EDITORS : Porter P. Lowry II ; Zachary S. Rogers ASSISTANTS DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITORS : Emmanuel Côtez ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Emmanuel Côtez COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : P. Baas (Nationaal Herbarium Nederland, Wageningen) F. Blasco (CNRS, Toulouse) M. W. Callmander (Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève) J. A. Doyle (University of California, Davis) P. K. Endress (Institute of Systematic Botany, Zürich) P. Feldmann (Cirad, Montpellier) L. Gautier (Conservatoire et Jardins botaniques de la Ville de Genève) F. Ghahremaninejad (Kharazmi University, Téhéran) K. Iwatsuki (Museum of Nature and Human Activities, Hyogo) K. Kubitzki (Institut für Allgemeine Botanik, Hamburg) J.-Y. Lesouef (Conservatoire botanique de Brest) P. Morat (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) J. Munzinger (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Montpellier) S. E. Rakotoarisoa (Millenium Seed Bank, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Madagascar Conservation Centre, Antananarivo) É. A. Rakotobe (Centre d’Applications des Recherches pharmaceutiques, Antananarivo) P. H. Raven (Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis) G. Tohmé (Conseil national de la Recherche scientifique Liban, Beyrouth) J. G. West (Australian National Herbarium, Canberra) J. R. Wood (Oxford) COUVERTURE / COVER : Made from the figures of the article. Adansonia est -

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes Shichao Chen1., Dong-Kap Kim2., Mark W. Chase3, Joo-Hwan Kim4* 1 College of Life Science and Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2 Division of Forest Resource Conservation, Korea National Arboretum, Pocheon, Gyeonggi- do, Korea, 3 Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Abstract Phylogenetic analysis aims to produce a bifurcating tree, which disregards conflicting signals and displays only those that are present in a large proportion of the data. However, any character (or tree) conflict in a dataset allows the exploration of support for various evolutionary hypotheses. Although data-display network approaches exist, biologists cannot easily and routinely use them to compute rooted phylogenetic networks on real datasets containing hundreds of taxa. Here, we constructed an original neighbour-net for a large dataset of Asparagales to highlight the aspects of the resulting network that will be important for interpreting phylogeny. The analyses were largely conducted with new data collected for the same loci as in previous studies, but from different species accessions and greater sampling in many cases than in published analyses. The network tree summarised the majority data pattern in the characters of plastid sequences before tree building, which largely confirmed the currently recognised phylogenetic relationships. Most conflicting signals are at the base of each group along the Asparagales backbone, which helps us to establish the expectancy and advance our understanding of some difficult taxa relationships and their phylogeny. -

The First Record of Ephedra Distachya L. (Ephedraceae, Gnetophyta) in Serbia - Biogeography, Coenology, and Conservation

42 (1): (2018) 123-138 Original Scientific Paper The first record of Ephedra distachya L. (Ephedraceae, Gnetophyta) in Serbia - Biogeography, coenology, and conservation - Marjan Niketić Natural History Museum in Belgrade, Njegoševa 51, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia ABSTRACT: During floristic investigations of eastern Serbia (foothills of the Stara Planina Mountains near Minićevo, Turjačka Glama hill), Ephedra distachya (Ephedraceae) was discovered as a species new for the vascular flora of Serbia. An overview of the family, genus, and species is given in the present paper. In addition, two phytocoenological relevés recorded in the species habitat are classified at the alliance level. The IUCN threatened status of the population in Serbia is assessed as Critically Endangered. Keywords: Ephedra distachya, Ephedraceae, new record, Stara Planina Mountains, flora of Serbia Received: 13 September 2017 Revision accepted: 28 November 2017 UDC: 497.11:581.95 DOI: INTRODUCTION Stevenson (1993), and Fu et al. (1999). The distribution of E. distachya in the Southeast Europe is mapped on a In spite of continuous and intensive investigations of 50×50 km MGRS grid system (Lampinen 2001) based the Serbian flora at the end of the 20th century (Josifo- on the species distribution map in the Atlas Florae Euro- vić 1970-1977; Sarić & Diklić 1986; Sarić 1992; Ste- paeae (Jalas & Suominen 1973) and supplemented and/ vanović 1999), numerous new species and even higher or confirmed by chrorological records from Stoyanov taxa were recorded in the past two decades (Stevanović (1963), Horeanu & Viţalariu (1992), Christensen 2015). Last year, Ephedra distachya L. − a relict species (1997), Sanda et al. (2001), Tzonev et al. -

In Vitro Antimicrobial Synergism Within Plant Extract Combinations from Three

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 139 (2012) 81–89 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm In vitro antimicrobial synergism within plant extract combinations from three South African medicinal bulbs ∗ B. Ncube, J.F. Finnie, J. Van Staden Research Centre for Plant Growth and Development, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg, Private Bag X01, Scottsville 3209, South Africa a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Tulbaghia violacea, Hypoxis hemerocallidea and Merwilla plumbea are used Received 27 July 2011 in South African traditional medicine for the treatment of some infectious diseases and other ailments. Received in revised form Aim of the study: The study aimed at investigating the antimicrobial efficacies of independent and various 21 September 2011 within-plant extract combinations of three medicinal bulbs to understand the possible pharmacological Accepted 15 October 2011 interactions. Available online 30 October 2011 Materials and methods: Bulb and leaf extracts of the three medicinal plants, independently and in com- binations, were comparatively assessed for antimicrobial activity against two Gram-positive and two Keywords: Antimicrobial Gram-negative bacteria and Candida albicans using the microdilution method. The fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FIC) for two extract combinations were determined. Extract combination Interaction Results: At least one extract combination in each plant sample demonstrated good antimicrobial activity Phytochemical against all the test organisms. The efficacies of the various extract combinations in each plant sample Synergy varied, with the strongest synergistic effect exhibited by the proportional extract yield combination of PE and DCM extracts in Merwilla plumbea bulb sample against Staphylococcus aureus (FIC index of 0.1). -

CREW Newsletter – 2021

Volume 17 • July 2021 Editorial 2020 By Suvarna Parbhoo-Mohan (CREW Programme manager) and Domitilla Raimondo (SANBI Threatened Species Programme manager) May there be peace in the heavenly virtual platforms that have marched, uninvited, into region and the atmosphere; may peace our homes and kept us connected with each other reign on the earth; let there be coolness and our network of volunteers. in the water; may the medicinal herbs be healing; the plants be peace-giving; may The Custodians of Rare and Endangered there be harmony in the celestial objects Wildflowers (CREW), is a programme that and perfection in eternal knowledge; may involves volunteers from the public in the everything in the universe be peaceful; let monitoring and conservation of South peace pervade everywhere. May peace abide Africa’s threatened plants. CREW aims to in me. May there be peace, peace, peace! capacitate a network of volunteers from a range of socio-economic backgrounds – Hymn of peace adopted to monitor and conserve South Africa’s from Yajur Veda 36:17 threatened plant species. The programme links volunteers with their local conservation e are all aware that our lives changed from the Wend of March 2020 with a range of emotions, agencies and particularly with local land from being anxious of not knowing what to expect, stewardship initiatives to ensure the to being distressed upon hearing about friends and conservation of key sites for threatened plant family being ill, and sometimes their passing. De- species. Funded jointly by the Botanical spite the incredible hardships, we have somehow Society of South Africa (BotSoc), the Mapula adapted to the so-called new normal of living during Trust and the South African National a pandemic and are grateful for the commitment of the CREW network to continue conserving and pro- Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), CREW is an tecting our plant taxa of conservation concern. -

Journal of Ethnopharmacology a Broad Review of Commercially Important Southern African Medicinal Plants

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 119 (2008) 342–355 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Review A broad review of commercially important southern African medicinal plants B.-E. van Wyk ∗ Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Aims of the study: Commercially important indigenous medicinal plants of southern Africa are reviewed Received 8 May 2008 in the context of fundamental knowledge about their ethnobotany, phylogeny, genetics, taxonomy, bio- Received in revised form 14 May 2008 chemistry, chemical variation, reproductive biology and horticulture. The aim is to explore the rapidly Accepted 16 May 2008 increasing number of scientific publications and to investigate the need for further research. Available online 3 June 2008 Materials and methods: The Scopus (Elsevier) reference system was used to investigate trends in the number of scientific publications and patents in 38 medicinal plant species. Fifteen species of special Keywords: commercial interest were chosen for more detailed reviews: Agathosma betulina, Aloe ferox, Artemisia Biosystematics Chemical variation afra, Aspalathus linearis, Cyclopia genistoides, Harpagophytum procumbens, Hoodia gordonii, Hypoxis heme- Commercial development rocallidea, Lippia javanica, Mesembryanthemum tortuosum, Pelargonium sidoides, Siphonochilus aethiopicus, Medicinal plants Sutherlandia frutescens, Warburgia salutaris and Xysmalobium undulatum. Southern Africa Results: In recent years there has been an upsurge in research and development of new medicinal products Taxonomy and new medicinal crops, as is shown by a rapid increase in the number of scientific publications and patents. Despite the fact that an estimated 10% of the plant species of the world is found in southern Africa, only a few have been fully commercialized and basic scientific information is often not available. -

The First Record of Ephedra Distachya L. (Ephedraceae, Gnetophyta) in Serbia - Biogeography, Coenology, and Conservation

42 (1): (2018) 123-138 Original Scientific Paper The first record of Ephedra distachya L. (Ephedraceae, Gnetophyta) in Serbia - Biogeography, coenology, and conservation - Marjan Niketić Natural History Museum in Belgrade, Njegoševa 51, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia ABSTRACT: During floristic investigations of eastern Serbia (foothills of the Stara Planina Mountains near Minićevo, Turjačka Glama hill), Ephedra distachya (Ephedraceae) was discovered as a species new for the vascular flora of Serbia. An overview of the family, genus, and species is given in the present paper. In addition, two phytocoenological relevés recorded in the species habitat are classified at the alliance level. The IUCN threatened status of the population in Serbia is assessed as Critically Endangered. Keywords: Ephedra distachya, Ephedraceae, new record, Stara Planina Mountains, flora of Serbia Received: 13 September 2017 Revision accepted: 28 November 2017 UDC: 497.11:581.95 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1173568 INTRODUCTION Stevenson (1993), and Fu et al. (1999). The distribution of E. distachya in the Southeast Europe is mapped on a In spite of continuous and intensive investigations of 50×50 km MGRS grid system (Lampinen 2001) based the Serbian flora at the end of the 20th century (Josifo- on the species distribution map in the Atlas Florae Euro- vić 1970-1977; Sarić & Diklić 1986; Sarić 1992; Ste- paeae (Jalas & Suominen 1973) and supplemented and/ vanović 1999), numerous new species and even higher or confirmed by chrorological records from Stoyanov taxa were recorded in the past two decades (Stevanović (1963), Horeanu & Viţalariu (1992), Christensen 2015). Last year, Ephedra distachya L. − a relict species (1997), Sanda et al.