Communicate Hope to Motivate Action Against Highly Infectious SARS-Cov-2 Variants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing the Next Zoonotic Pandemic Strengthening and Extending the One Health Approach to Avert Pandemics of Animal Origin in the Region © FAO/Eran Rai�Man

FAO COVID-19 Response and Recovery Programme: Europe and Central Asia Preventing the next zoonotic pandemic Strengthening and extending the One Health approach to avert pandemics of animal origin in the region © FAO/Eran Raiman The issue Budget : USD 2 million SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, probably originated from an animal source, similar to 60 percent of all human infectious diseases. The Time frame: 2020–2024 pandemic has emphasized the need to prepare for, prevent, detect and respond to diseases at primary spillover level, where a new pandemic is SDGs likely to start. Pathogens are most likely to spread in locations where wildlife comes into contact with livestock production, particularly where people earn livelihoods, such as in live animal markets, areas where bushmeat is hunted, traded and consumed, or where growing pressures on natural ecosystems has forced livestock, wildlife and humans into close proximity. As a result, family farmers, especially women and children, are at high risk. Preventing spillover at source and mitigating the emergence and spread of pandemics requires a holistic and participatory One Health approach, involving experts, policymakers and communities in high-risk settings. Related FAO policy briefs The zoonotic nature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was established long before One Health legislation. Contributing to COVID-19 had evolved into a pandemic. Investigations into potential pandemic prevention through law animal hosts for this and other coronaviruses are pivotal to improve our understanding of COVID-19’s epidemiology, as well as to identify (and Integrated agriculture water minimize) sources for human infection. COVID-19 infection in animals sharing management and health the same space as humans comes as no surprise, given the prevalence of environmental contamination in households with the causative virus. -

IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics Report

IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics WORKSHOP REPORT *** Strictly Confidential and Embargoed until 3 p.m. CET on 29 October 2020 *** Please note: This workshop report is provided to you on condition of strictest confidentiality. It must not be shared, cited, referenced, summarized, published or commented on, in whole or in part, until the embargo is lifted at 3 p.m. CET/2 p.m. GMT/10 a.m. EDT on Thursday, 29 October 2020 This workshop report is released in a non-laid out format. It will undergo minor editing before being released in a laid-out format. Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 1 The IPBES Bureau and Multidisciplinary Expert Panel (MEP) authorized a workshop on biodiversity and pandemics that was held virtually on 27-31 July 2020 in accordance with the provisions on “Platform workshops” in support of Plenary- approved activities, set out in section 6.1 of the procedures for the preparation of Platform deliverables (IPBES-3/3, annex I). This workshop report and any recommendations or conclusions contained therein have not been reviewed, endorsed or approved by the IPBES Plenary. The workshop report is considered supporting material available to authors in the preparation of ongoing or future IPBES assessments. While undergoing a scientific peer-review, this material has not been subjected to formal IPBES review processes. 2 Contents 4 Preamble 5 Executive Summary 12 Sections 1 to 5 14 Section 1: The relationship between people and biodiversity underpins disease emergence and provides opportunities -

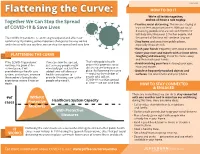

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic

COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city of area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Report Design: Michelle Hopgood, Toronto, Canada Icon Illustrator: Janet McLeod Wortel Maps: Taylor Blake COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic by The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response 2 of 86 Contents Preface 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The devastating reality of the COVID-19 pandemic 10 3. The Panel’s call for immediate actions to stop the COVID-19 pandemic 12 4. What happened, what we’ve learned and what needs to change 15 4.1 Before the pandemic — the failure to take preparation seriously 15 4.2 A virus moving faster than the surveillance and alert system 21 4.2.1 The first reported cases 22 4.2.2 The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern 24 4.2.3 Two worlds at different speeds 26 4.3 Early responses lacked urgency and effectiveness 28 4.3.1 Successful countries were proactive, unsuccessful ones denied and delayed 31 4.3.2 The crisis in supplies 33 4.3.3 Lessons to be learnt from the early response 36 4.4 The failure to sustain the response in the face of the crisis 38 4.4.1 National health systems under enormous stress 38 4.4.2 Jobs at risk 38 4.4.3 Vaccine nationalism 41 5. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

Community's Misconception About COVID-19 and Its Associated

Mekonnen et al. Tropical Medicine and Health (2020) 48:99 Tropical Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00279-8 and Health RESEARCH Open Access Community’s misconception about COVID- 19 and its associated factors among Gondar town residents, Northwest Ethiopia Habtamu Sewunet Mekonnen1* , Abere Woretaw Azagew1, Chalachew Adugna Wubneh2, Getaneh Mulualem Belay2, Nega Tezera Assimamaw2, Chilot Desta Agegnehu3, Telake Azale4, Zelalem Nigussie Azene5, Mehari Woldemariam Merid6, Atalay Goshu Muluneh6, Demiss Mulatu Geberu7, Getahun Molla Kassa6, Melaku Kindie Yenit6, Sewbesew Yitayih Tilahun8, Kassahun Alemu Gelaye6, Animut Tagele Tamiru9, Bayew Kelkay Rade9, Eden Bishaw Taye10, Asefa Adimasu Taddese6, Zewudu Andualem11, Henok Dagne11, Kiros Terefe Gashaye12, Gebisa Guyasa Kabito11, Tesfaye Hambisa Mekonnen11, Sintayehu Daba Wami11, Jember Azanaw11, Tsegaye Adane11 and Mekuriaw Alemayehu11 Abstract Background: Despite the implementation of various strategies such as the declaration of COVID-19 emergency state, staying at home, lockdown, and massive protective equipment distribution, still COVID-19 is increasing alarmingly. Therefore, the study aimed to assess the community’s perception of COVID-19 and its associated factors in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was employed among 635 Gondar administrative town residents, from April 20 to April 27, 2020. Study participants were selected using a cluster sampling technique. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. Epi-Data version 4.6 and STATA 14 were used for data entry and analysis, respectively. Logistic regressions (bivariable and multivariable) were performed to identify statistically significant variables at p <0.05. Results: Of the 635 study participants, 623 have completed the study with a 98.1% response rate. -

Genomic Sequencing of SARS-Cov-2: a Guide to Implementation for Maximum Impact on Public Health

Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 A guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health 8 January 2021 Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 A guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health 8 January 2021 Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: a guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health ISBN 978-92-4-001844-0 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-001845-7 (print version) © World Health Organization 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules/). -

WHO COVID-19 Database Search Strategy (Updated 26 May 2021)

Search purpose: Systematic search of the COVID-19 literature performed Monday through Friday for the WHO Database. Search strategy as of 26 May 2021. Searches performed by Tomas Allen, Kavita Kothari, and Martha Knuth. Use following commands to pull daily new entries: Entry_date:( [20210101 TO 20210120]) Entry_date:( 20210105) Duplicates: Duplicates are found in EndNote and Distillr using the Wichor method. Further screening is done by expert reviewers but some duplicates may still be in the database. Daily Search Strategy: Database Daily Search Strategy Medline (coronavir* OR corona virus* OR corona pandemic* OR betacoronavir* OR covid19 OR covid OR (Ovid) nCoV OR novel CoV OR CoV 2 OR CoV2 OR sarscov2 OR sars2 OR 2019nCoV OR wuhan virus* OR 1946- NCOV19 OR solidarity trial OR operation warp speed OR COVAX OR "ACT-Accelerator" OR BNT162b2 OR comirnaty OR "mRNA-1273" OR CoviShield OR AZD1222 OR Sputnik V OR CoronaVac OR "BBIBP-CorV" OR "Ad26.CoV2.S" OR "JNJ-78436735" OR Ad26COVS1 OR VAC31518 OR EpiVacCorona OR Convidicea OR "Ad5-nCoV" OR Covaxin OR CoviVac OR ZF2001 OR "NVX-CoV2373" OR "ZyCoV-D" OR CIGB 66 OR CVnCoV OR "INO-4800" OR "VIR-7831" OR "UB-612" OR BNT162 OR Soberana 1 OR Soberana 2 OR "B.1.1.7" OR "VOC 202012/01" OR "VOC202012/01" OR "VUI 202012/01" OR "VUI202012/01" OR "501Y.V1" OR UK Variant OR Kent Variant OR "VOC 202102/02" OR "VOC202102/02" OR "B.1.351" OR "VOC 202012/02" OR "VOC202012/02" OR "20H/501.V2" OR "20H/501Y.V2" OR "501Y.V2" OR "501.V2" OR South African Variant OR "B.1.1.28.1" OR "B.1.1.28" OR "B.1.1.248" OR -

Covid-19 Response and Recovery

COVID-19 RESPONSE AND RECOVERY Nature-Based Solutions for People, Planet and Prosperity Recommendations for Policymakers November 2020 Nicole Schwab Elena Berger Co-Director Executive Director 1t.org Bank Information Center Patricia Zurita M. Sanjayan CEO CEO Birdlife International Conservation International Mark Gough Kathleen Rogers CEO President Capitals Coalition Earth Day Network Andrea Crosta Carlos Manuel Rodriguez Founder and Executive Director CEO and Chairperson Earth League International Global Environment Facility Wes Sechrest Paul Polman Chief Scientist and CEO Chair Global Wildlife Conservation Imagine Azzedine Downes Karen B. Strier President and CEO President International Fund for Animal Welfare International Primatological Society II Sylvia Earle Lucy Almond President and Chair Director and Chair Mission Blue Nature4Climate Jennifer Morris Bonnie Wyper CEO President The Nature Conservancy Thinking Animals United Justin Adams Cristián Samper Executive Director President and CEO Tropical Forest Alliance Wildlife Conservation Society Peter Bakker President and CEO Andrew Steer World Business Council for President and CEO Sustainable Development World Resources Institute Jodi Hilty Marco Lambertini President and Chief Scientist Director General Yellowstone to Yukon WWF International Conservation Initiative III Executive Summary COVID-19 highlights the critical connection between the health of nature and human health. This connection must be better reflected in our priorities, policies and actions. The root causes of this pandemic are common to many root causes of the climate change and biodiversity crises. Confronting these intertwined crises requires an integrated approach and unprecedented cooperation to achieve an equitable carbon-neutral, nature-positive economic recovery and a sustainable future. Our organizations’ recommendations to policymakers for meeting this challenge are offered below. -

COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevention and Protection Measures to Be Adopted at the Workplace

sustainability Protocol COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevention and Protection Measures to Be Adopted at the Workplace Luigi Cirrincione 1, Fulvio Plescia 1 , Caterina Ledda 2 , Venerando Rapisarda 2, Daniela Martorana 3, Raluca Emilia Moldovan 4, Kelly Theodoridou 5 and Emanuele Cannizzaro 1,* 1 Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties “Giuseppe D’Alessandro”, University of Palermo, 90127 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (L.C.); [email protected] (F.P.) 2 Occupational Medicine, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine University of Catania Italy, 95131 Catania, Italy; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (V.R.) 3 Department of Orthopedics, Hospital Company “Ospedali Riuniti Villa Sofia-Cervello” Palermo Italy, 90146 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Economics within Dimitrie Cantemir University of Targu Mures, 540680 Targu Mures, Romania; [email protected] 5 Department of Microbiology A Syggros University Hospital Athens Greece, 10552 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 April 2020; Accepted: 27 April 2020; Published: 29 April 2020 Abstract: SARS-CoV-2, identified in Wuhan, China, for the first time in December 2019, is a new viral strain, which has not been previously identified in humans; it can be transmitted both by air and via direct and indirect contact; however, the most frequent way it spreads is via droplets. Like the other viruses belonging to the same family of coronaviruses, it can cause from mild flu-like symptoms, such as cold, sore throat, cough and fever, to more severe ones such as pneumonia and breathing difficulties, and it can even lead to death. -

Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery

x Chapter 1 Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery The beginning of 2020 ushered in a strong U.S. economy that was delivering job, income, and wealth gains to Americans of all backgrounds. By February 2020, the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.5 percent—the lowest in 50 years— and unemployment rates for minority groups and historically disadvantaged Americans were at or near their lowest points in recorded history. Wages were rising faster for workers than for managers, income and wealth inequality were on the decline, and median incomes for minority households were experienc- ing especially rapid gains. The fruits of this strong labor market expansion from 2017 to 2019 also included lifting 6.6 million people out of poverty, which is the largest three-year drop to start any presidency since the War on Poverty began in 1964. These accomplishments highlight the success of the Trump Administration’s pro-growth, pro-worker policies. The robust state of the U.S. economy in the three years through 2019 led almost all forecasters to expect continued healthy growth through 2020 and beyond. However, in late 2019 and the early months of 2020, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, with origins in the People’s Republic of China, began spreading around the globe and eventually within the United States, causing a pandemic and bringing with it an unprecedented economic and public health crisis. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy suffered sudden and massive shocks due to the pandemic. During the springtime lockdowns aimed at “flattening the curve,” the labor market lost 22.2 million jobs, and the unemployment rate jumped 11.2 percentage points, to 14.7 percent—the largest monthly changes in the series’ histories. -

COVID-19 & the Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why Did Sweden Not Lock

COVID-19 & The Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why did Sweden not lock down? What were they trying to achieve? Prathap Tharyan The world is cautiously trying to emerge from lockdowns People enjoying the sun in Stockholm on April 21, 2020 Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP via Getty images (Business Insider May 4 2020) No Lockdown: Do the Swedes know something the rest of the world does not know? Or are they playing “Russian Roulette” with their “Herd Immunity” strategy? SWEDEN’S RELAXED CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE NO LOCKDOWN IN SWEDEN: A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT IN COMBATING COVID-19 Cafes, bars, restaurants, elementary schools and most businesses, including hair salons and gyms are open and people are allowed to exercise outdoors Parks and public spaces are open Pubs and bars remain open https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/28/europe/sweden- Photograph: Ali Lorestani/EPA (The Guardian March 23) coronavirus-lockdown-strategy-intl/index.html WHY IS SWEDEN IS ‘DOING NOTHING’? Advice from the Public Health Agency Sweden has recommended good hygiene as part of infection control “Face masks are meant for Sweden’s Public Health Agency healthcare staff and not needed in in does not recommend face masks the community. for the public The best way to protect oneself and others in daily life is to maintain social distancing and good hand hygiene” SWEDISH PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY RECOMMENDS SOCIAL DISTANCING No large gatherings (50 people max.) Does not apply to schools, public transport, gyms Work from home if possible Keep arms-length distance from others in all public spaces including