Rick Hazlett Stephen M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

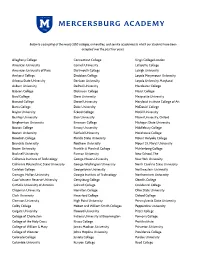

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

A Walking Tour

Office of Admission Occidental College: A Walking Tour Welcome to Occidental College! We’re excited you’re visiting Oxy and we want your experience to give you a good feel for life on campus. With that in mind, we’ve created a self-guided tour to provide you with information about several aspects of campus. We hope you will enjoy information about our rich heritage, art, intellectual community, civic engagement, and on and off-campus opportunities. Using this as an exploratory tool, refer to our campus map to navigate your way through campus. For quick facts and figures, please refer to the back of our campus map and the Oxy website (www.oxy.edu). WHAT IS OCCIDENTAL? Occidental College is a private, residential liberal arts and sciences undergraduate institution located in the city of Los Angeles. Founded on a commitment to excellence, equity, community, and service, our academic offerings and social engagement opportunities expand beyond Campus Road. Oxy students have access to Los Angeles, while still enjoying a tight-knit community. Oxy students are passionate, motivated, collaborative, and highly involved in their own education. Our student body is civically engaged, globally aware, and in pursuit of hands-on learning. TAKE A STEP: Beginning at the Office of Admission, walk to Gilman Road and head down the hill. Your first stop is Weingart Center for the Liberal Arts, Building 17. Explore the galleries inside Weingart or sit down outside and enjoy the shade. WEINGART CENTER FOR THE LIBERAL ARTS Housed inside Weingart are offices for two of Oxy’s unique majors: Critical Theory and Social Justice and Media Arts & Culture. -

Pomona College Magazine Fall/Winter 2020: the New (Ab

INSIDE:THE NEW COLLEGE MAGAZINE (AB)NORMAL • The Economy • Childcare • City Life • Dating • Education • Movies • Elections Fall-Winter 2020 • Etiquette • Food • Housing •Religion • Sports • Tourism • Transportation • Work & more Nobel Laureate Jennifer Doudna ’85 HOMEPAGE Together in Cyberspace With the College closed for the fall semester and all instruction temporarily online, Pomona faculty have relied on a range of technologies to teach their classes and build community among their students. At top left, Chemistry Professor Jane Liu conducts a Zoom class in Biochemistry from her office in Seaver North. At bottom left, Theatre Professor Giovanni Molina Ortega accompanies students in his Musical Theatre class from a piano in Seaver Theatre. At far right, German Professor Hans Rindesbacher puts a group of beginning German students through their paces from his office in Mason Hall. —Photos by Jeff Hing STRAY THOUGHTS COLLEGE MAGAZINE Pomona Jennifer Doudna ’85 FALL/WINTER 2020 • VOLUME 56, NO. 3 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry The New Abnormal EDITOR/DESIGNER Mark Wood ([email protected]) e’re shaped by the crises of our times—especially those that happen when ASSISTANT EDITOR The Prize Wwe’re young. Looking back on my parents’ lives with the relative wisdom of Robyn Norwood ([email protected]) Jennifer Doudna ’85 shares the 2020 age, I can see the currents that carried them, turning them into the people I knew. Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work with They were both children of the Great Depression, and the marks of that experi- BOOK EDITOR the CRISPR-Cas9 molecular scissors. Sneha Abraham ([email protected]) ence were stamped into their psyches in ways that seem obvious to me now. -

Pitzer College Editorial and Graphic Standard Style Guide

1 Style Guide Graphic Standards & Editorial Guidelines Introduction Introduction The Office of Communications is responsible for the quality and consistency of the College’s communications efforts, including but not limited to event publicity, media relations, news dissemination, publications, advertising, use of logos and the College’s official Website. We tell the world about Pitzer College every day with accuracy and clarity, and we want this important message, whether in the form of a news release, brochure, magazine or newsletter or ad, to be consistent in its content and style. Our ultimate goal, and one we all share as representatives of Pitzer, is to put a face on the College that is so strong and crystal clear that our audiences will immediately connect the Pitzer experience with successful students, faculty, staff and alumni that lead fulfilling lives with an emphasis on social responsibility, critical thinking, intercultural understanding and environmental sensitivity. Because of the naturally wide scope of the College’s communications and in an effort to serve you better, the Office of Communications has established certain procedures and policies, laid out in this guide, to facilitate this campus-wide cooperation. 2 Style Guide Marketing, Publications and Advertising The Office of Communications can advise you on identifying your target audiences, how to get the most for your money, the many different routes available to promote your department or event, how to develop realistic project timelines, which vendors best suit your needs and more. All advertising and marketing efforts should be approved by the Office of Communications for consistency with the image of the institution, factual accuracy, appropriate use of photos, correct grammar and punctuation and correct use of graphics and style. -

ASHE-Sponsored and Co-Sponsored Sessions at the Western Economic Association Conference

ASHE-sponsored and co-sponsored sessions at the Western Economic Association conference [84] Saturday, June 29 @ 10:15 am–12:00 pm Allied Societies: CSWEP, CSMGEP, and ASHE (and Professional Development) PANEL OF JOURNAL EDITORS OFFERING ADVICE ON PUBLISHING Organizer(s): Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, San Diego State University, and T. Renee Bowen, Stanford University Moderator: Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, San Diego State University Panelists: Hilary W. Hoynes, University of California, Berkeley Brad R. Humphreys, West Virginia University Charles I. Jones, Stanford University Wesley W. Wilson, University of Oregon [186] Sunday, June 30 @ 8:15 am–10:00 am Allied Society: ASHE ETHNICITY, MIGRATION, AND HUMAN CAPITAL Organizer(s): Fernando Antonio Lozano, Pomona College Chair: Mary J. Lopez, Occidental College Papers: Immigrant English Proficiency and the Academic Performance of Their Children *Alberto Ortega, Whitman College, and Tyler Ludwig, University of Virginia Do Social Learning Skills Improve Cognitive and Noncognitive Skills *Cary Cruz Bueno, Georgia State University Nontraditional Returns to Skill by Race and Ethnicity? Evidence from the PIAAC Prison *Anita Alves Pena, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and Thomas Briggs, Colorado State University, Fort Collins Local Financial Shocks and Its Effect on Crime *Salvador Contreras, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, and Amit Ghosh, Illinois Wesleyan University Informal Care-giving and the Labor Market Outcomes of Grandparents *Enrique Lopezlira, Grand Canyon University (Colangelo College of Business) Discussants: Melanie Khamis, Wesleyan University Fernando Antonio Lozano, Pomona College Eduardo Saucedo, Tecnologico de Monterrey Marie T. Mora, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley [210] Sunday, June 30 @ 2:30 pm–4:15 pm Allied Society: ASHE FINANCE AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE Organizer(s): Raffi Garcia, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Chair: Raffi Garcia, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Papers: Global Perceptions of the United States and International Student Enrollments *Mary J. -

College Counseling Program

College Counseling Program The Oregon Episcopal School college counseling team works closely with students as they search for colleges in which they will thrive. Encouraging them to take ownership of the experience, we combine individualized advice with programs and resources designed to help students—and their families—navigate the search and application phases in a thoughtful manner. Throughout high school, we provide guidance, perspective, and timely information intended to demystify the process and encourage wise choices. Underpinning our approach is a desire to have students make the most of their high school experience in a healthy, balanced manner. COLLEGE NIGHTS FOR PARENTS We offer workshops for parents, tailored by grade level, to learn about the college search process, and a presentation on financing college. For more information, visit: COLLEGE ATTENDANCE oes.edu/college Graduates of OES attend an impressive array of colleges throughout the United States and internationally. OES has an excellent, well-established reputation with colleges across the country and hosts visits from over 130 college representatives in a typical year. Colleges Attended Public vs. Private Public 29% 71% Private Non U.S.: 4% Admissions 6300 SW Nicol Road | Portland, OR 97223 | 503-768-3115 | oes.edu/admissions OES STUDENTS FROM THE CLASSES OF 2020 AND 2021 WERE ACCEPTED TO THE FOLLOWING COLLEGES Acadia University Elon University Pomona College University of Chicago Alfred University Emerson College Portland State University University of Colorado, -

2007-2009 College Catalog

WWHITTIERWHITTIER CCOLLEGEOLLEGE 2007-2009 ISSUE OF THE WHITTIER COLLEGE CATALOG Volume 89 • Spring 2007 Published by Whittier College, Offi ce of the Registrar 13406 E. Philadelphia Street, P.O. Box 634, Whittier, CA 90608 • (562) 907-4200 • www.whittier.edu Accreditation Whittier College is regionally accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges. You may contact WASC at: 985 Atlantic Avenue, SUITE 100 Alameda, CA 94501 (510) 748-9001 The Department of Education of the State of California has granted the College the right to recommend candidates for teaching credentials. The College’s programs are on the approved list of the American Chemical Society, the Council on Social Work Education, and the American Association of University Women. Notice of Nondiscrimination Whittier College admits students of any race, color, national or ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, marital status, sexual orientation, national or ethnic origin in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, or athletic and other school-administered programs. Whittier College does not discriminate on the basis of disability in admission or access to its programs. Fees, tuition, programs, courses, course content, instructors, and regulations are subject to change without notice. 2 TTABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW ..................................................................................Inside -

U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association

U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association 1984 All Americans Division III Outdoor Track & Field Event Gender Last Name First Name School 100m Men Baker Stanford Olivet College Greven John State University College at Fredonia Hardy Malcolm Occidental College Lampley Deverick Millikin University Rippy Derrick Mount Union College Taylor Neil University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh Women Armstead Tracey State University College at Cortland Boxley Karen Fisk University Cisar Nancy Central College (Iowa) Edwards Margo University of Redlands Jones Michele Rochester Institute of Technology Mazurik Michelle University of Rochester 200m Men Brooks Tyrone Bishop College Fearon Barry Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) Lampley Deverick Millikin University Rippy Derrick Mount Union College Ruffin Alonzo Southern University at New Orleans Taylor Neil University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh Women Armstead Tracey State University College at Cortland Boggs Sharon Fitchburg State College Cisar Nancy Central College (Iowa) Edwards Margo University of Redlands Murphy Sandra The College of New Jersey Perkins Maudrey May Southern University at New Orleans 400m Men Dixon Kirk St. Lawrence University Fearon Barry Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) Galatas Derek Southern University at New Orleans Ruffin Alonzo Southern University at New Orleans (c) USTFCCCA Page 1 of 11 1984 All Americans Division III Outdoor Track & Field Event Gender Last Name First Name School Swanberg David Concordia College, Moorhead Thompson Fred State University College at Fredonia Women -

Handbook for Department Chairs and Program Coordinators

Pomona College Handbook for Department Chairs, Program Coordinators, and Directors 2021-22 1 POMONA COLLEGE HANDBOOK FOR DEPARTMENT CHAIRS, PROGRAM COORDINATORS, AND DIRECTORS ........................................................................................................................................1 Contact Information in the Dean’s Office .......................................................................................................... 6 Overview of Department Chair Responsibilities ................................................................................................. 7 Departmental Planning .................................................................................................................................... 9 Availability.................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Curriculum Overview and Catalog Planning .............................................................................................................. 9 Planning Sabbatical and Other Leaves....................................................................................................................... 9 Advising ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Changes to Majors and Minors ............................................................................................................................... -

The Rock, December, 1949 (Vol

Whittier College Poet Commons The Rock Archives and Special Collections 12-1949 The Rock, December, 1949 (vol. 11, no. 3) Whittier College Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/rock _1i t4O BASK T 90.z1 351k Hrr N 17 'will he go.273f R GAUFC 73 ITTlTl ' - L ".2,73 -.---.- -The W141-TTIER ,,' 'l fr .- _4•'_ Oli1' NVIIATTI -oR'' ----- - \V U1 - o ThE ROV A ST REETCAR RIDE TO A DOCTO R'S D EG REE (SEE PAGE 13) I Eaokz i 'LEEth21 THE ROCK !25e424 &74ien & . & 0 OF Another Homecoming is a thing Ken Beyer... of the past and we look to the next WHITTIER COLLEGE one with anticipation for we know Kenneth Beyer G. Duncan Wimpress that as each year goes by the annual Associate Editors affair at the college improves. The attendance this year at general affairs such as brunches and meetings was far above that of last year, but the ALUMNI OFFICERS attendance at the dinner was some- what lower. The number of persons 1949 attending the dinner this year was 347 as compared with 369 for 1948. President Edward J. Guirado, '28 Perhaps some of the decrease was Broadoaks President due to persons wanting to go to the Mrs. Howard Mills, '45 game earlier than they could have if Vice President John Hales, '41 they had attended the dinner. At- tendance at the game, as could well Secretary-Treasurer Ken Beyer, '47 be seen, was tremendously increased. Social Chairman Speaking of the Homecoming foot- Newton Robinson, '37 ball game following the dinner in the gym makes me feel that some sort of Historian Edna Nanney, '10 an explanation is due those unfor- Past President Paul Pickett, '22 tunates who did not get a seat in the reserved section as was promised them. -

Pomona College the Claremont Colleges Scripps College

The Claremont Colleges Mrs. Ferentz visited The Claremont Colleges February 2017. The Claremont Colleges is a consorum of 5 undergraduate liberal arts colleges nestled in beauful Southern California (1 hour east of Los Angeles). The undergraduate colleges include: Pomona College, Scripps College, Claremont McKenna College, Harvey Mudd College, and Pitzer College. Each of the Claremont Colleges is an independent instuon with its own student body, faculty, campus, mission and identy. Together, the col‐ leges form a rich intellectual network and offer cross‐registraon in courses, and share a bookstore, health and counseling services, recreaonal opportunies and a prisne two million volume library. Over 8,000 stu‐ dents aend the Claremont Colleges, and students connect and interact through over 250 clubs and more than 2,000 courses. Outdoor study spaces are abundant‐ from quiet rooop tables to manicured lawns and courtyards, there is ample space highlighted with the stunning San Gabriel mountains as the backdrop. Pomona College Pomona College was the first of the 5 built and the highest ranked amongst the consorum. It is a liberal arts college with small classes (8:1 student to faculty rao), as the founders envisioned a “New England type college” when designing the school. Pomona offers over 45 majors and 50% of students study abroad. Weekly guest speakers host lectures and students sign up in person to get the chance to sit with the guests, including Bill Clinton, Laverne Cox, and many others. “Ski‐Beach Day” takes advantage of the locaon: stu‐ dents ski at a local resort in the morning and then spend the aernoon at a beach in Orange County. -

“The Advancement of Senior Women Scientists at Liberal Arts Colleges”

Report and Recommendations Developed During the Inaugural Summit on “The AdvancementReport and Recommendations of Senior Women Scientists atDeveloped Liberal During Arts Colleges” the Inaugural Summit on Held June 2-4, 2010 “TheWashington, Advancement DC of Senior Women Scientists at This meeting was organizedLiberal by the co-principal Arts Colleges”investigators of a project funded by the National Science Foundation ADVANCE Partnerships for Adaptation, Implementation, and Dissemination (PAID) program. Leading the project are four full professors of chemistry: Professor Kerry Karukstis, Harvey Mudd College; Professor Laura Wright, Furman University; Professor Miriam Rossi, Vassar College; and Professor Bridget Gourley, DePauw University. The project created four "alliances" to study the effectiveness of horizontal mentoring to enhance the professional development of senior women chemistry and physics faculty members at liberal arts institutions. Three of the five-member alliances focusHeld on full June professor 2-4,s in chemistr 2010y, the fourth involves full professors in physics. Washington, DC This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants NSF-HRD- 0618940, 0619027, 0619052, and 0619150. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Integrating Work and a Personal Life: Aspects of Time and Stress Management for Senior Women Science Faculty, Julie T. Millard and Nancy S. Mills (Also published in ACS Symposium Series 1057) Report and Recommendations Outlines the challenges faced by faculty in creating an appropriate work- Report and Recommendations life balance with particular emphasis on particular pressures faced by senior Developed During the Inaugural Summit on women science faculty.