JOHN W. BALDWIN 13 July 1929 . 8 February 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

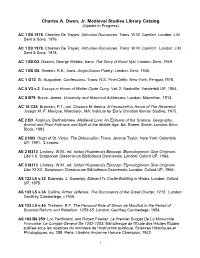

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1972, Volume 67, Issue No. 4

L HISTOR ICAL MAGAZINE •w^—a^—•«••_«•*•• Master of the Art of Canning Edward F. Keuchel The Vestry as a Unit of Local Government Gerald E. Hartdagen Captain Gordon of the Constellation Morris L. Radofl: Planning Roland Park Harry G. Schalck Vol. 67 No. 4 The Christmas Tree, 1858 — Winslow Home^ A QUARTERLY PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY GEORGE L. RADCLIFFE, Chairman of the Council SAMUEL HOPKINS, President C. A. PORTER HOPKINS, Vice President LEONARD C. CREWE, JR., Vice President JOHN G. EVANS, Treasurer S. VANNORT CHAPMAN, Recording Secretary A. RUSSELL SLAGLE, Corresponding Secretary WILLIAM B. MARYE, Corresponding Secretary Emeritus LEONARD C. CREWE, JR., Gallery DR. RHODA M. DORSEY, Publications MRS. BRYDEN B. HYDE, Women's LESTER S. LEVY, Addresses CHARLES L. MARBURG, Athenaeum ROBERT G. MERRICK, Finance ABBOTT L. PENNIMAN, JR., Athenaeum DR. THOMAS G. PULLEN, JR., Education GEORGE M. RADCLIFFE, Membership A. RUSSELL SLAGLE, Genealogy and Heraldry FREDERICK L. WEHR, Maritime DR. HUNTINGTON WILLIAMS, Library P. WILLIAM FILBY, Director Annual Subscription to the Magazine, $10.00. Each issue $2.50. The Magazine assumes no responsibility for statements or opinions expressed in its pages. Published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, Md. Second-Class postage paid at Baltimore, Md. HALL OF RECORDS LIBRARY BOARD OF EDITORS JEAN BAKER Goucher College RHODA M. DORSEY, Chairman Goucher College JACK P. GREENE Johns Hopkins University FRANCIS C. HABER University of Maryland AUBREY C. LAND University of Georgia BENJAMIN QUARLES Morgan State College MORRIS L. RADOFF Maryland State Archivist A. RUSSELL SLAGLE Baltimore RICHARD WALSH Georgetown University FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE 1906-1909 LOUIS H. -

Conferring of Degrees

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE Conferring of Degrees At The Close Of The Sixty-Fifth Academic Year JUNE 3, 1941 IN THE LYRIC THEATRE AT II A. M. MARSHALS Chief Marshal Professor William 0. Weyforth Aids Br. G. Heberton Evans Dr. Lawrence Eiggs Dr. Ronald T. Aberceombib Dr. W. Halset Barker Dr. Howard E. Cooper Dr. Gilbert F. Otto Mr. Myrick W. Pullen Dr. Sidney Painter USHERS Chief Usher Donald Hurst Wilson, Jr. Aids Thomas Worthington Brundige III John Clagett Ntjttlb Winston Truehart Brundige John Lauohheimer Rosenthal Howell Corbin Gwaltnet, Jr. Walter William Stauffen Wilson Ridgely Haines Leslie Stewart Wilson, Jr. Oliver Parry Winslow, Jr. MUSIC The program is under the direction of Philip S. Morgan of the Johns Hopkins Musical Association and is presented by the Johns Hopkins Orchestra, Bart Wirtz conducting. The orchestra was founded and endowed in 1919 by Edwin L. TurnbuU, of the Class of 1893, for the presentation of good music in the University and the conimunitj'. ——— ORDKR OF EXERCISES I ACADEMIO PrOOKSSION Marcho Milifairo—Schubert Coronation Marrhe Meyerbeer II Invocation The Eovcrciul .Tomm T. Galloway Miuister, Holand Park Presbyterian Church III Address President Isaiah Bowman IV CONFEHRINO OF DEGREES Bachelors of Arts, presented by Dean Berry Bachelors of Engineering, presented by Dean Kouwenhoven Bachelors of Science in Economics, presented by Professor Weyforth Bachelors of Science, presented by Professor Bambf,roer Master of Education, presented by Professor Bambercjer Doctors of Education, presented by Professor -

The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland Conferring Of

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIM RE MARYLAND O , C ONFERRI N G O F D EGREES AT TH E CLOS E O F TH E S EVENTY-FIRST ACADEMIC YEAR U NE 1 0 1 94 J , 7 GILMAN HALL TERRACE AT LE EN E V A . M . ORDER OF PROCESSION CHIEF MARSHAL G HEBEETON E JR . VANS, Divisions Marshals s th e E ER The Pre ident of University, S IDN Y PAINT the Chaplain, Honored Guests, the Trustees F cul R H A ER The a ty F ANCIS . GL US G RD E ER Chie The raduates H OWA . COOP , f R ox RICHA D T . C E ER JOHN C . G Y RE E L CLA NC D . ONG RD E H R F ELD RICHA . T U S I H E AR ER W. ALS Y B K G L BERT F OTT I . O HE R E N Y T . ROW LL USHERS — GRA E E S R . 0 hie sher U . NT P OPL , J f U ER E H LEVI COOP DANI L . N E FEA ERS‘ L JOHN . TH ROSS MACAU AY W N EL . TO M T BERT O JOHNS N IL ON R . RO S I LE R I ET H . G T C S C JOHN OPOLD AN . V The audience is re'uested to stand as the academi c procession moves into the area n i c and remain standi g unt l after the Invo ation . ORDER OF EXERCISES PROC ESSIONAL II I NVOCATION KEE E The Reverend WILLIAM A . -

I^Igtorical Hsfgociation

American i^igtorical Hsfgociation SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING CHICAGO, ILLINOIS HEADQUARTERS: THE CONRAD HILTON DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 50 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits THE DEVELOPMENT OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION Narrative Essays in the History of Our Tradition from Its Origins in Ancient Israel and Greece to the Present EDWARD W. FOX Cornell University, Editor THE AGE OF POWER. By Carl J. Friedrich, Harvard University, and Charles Blitzer, Yale University. 211 pages, paper, $1.75 THE AGE OF REASON. By Frank E. Manuel, Brandeis University. 155 pages, map, paper, $1.25 THE AGE OF REFORMATION. By E. Harris Harbison, Princeton Uni versity. 154 pages, maps, paper, $1.25 ANCIENT ISRAEL. By Harry M. Orlinsky, Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion. 202 pages, maps, paper, $1.75 THE DECLINE OF ROME AND THE RISE OF MEDIAEVAL EUROPE. By Solomon Katz, University of Washington. 173 pages, maps, paper, $1.25 THE EMERGENCE OF ROME AS RULER OF THE WESTERN WORLD. By Chester G. Starr, Jr., University of Illinois. 130 pages, maps, paper, $1.25 THE GREAT DISCOVERIES AND THE FIRST COLONIAL EM- PIRES. By Charles E. Nowell, University of Illinois. 158 pages, maps, paper, $1.25 THE MEDIAEVAL CHURCH. By Marshall W. Baldwin, New York University. 133 pages, paper, $1.25 MEDIAEVAL SOCIETY. By Sidney Painter, The Johns Hopkins Univer sity. 117 pages, chart, paper, $1.25 THE RISE OF THE FEUDAL MONARCHIES. By Sidney Painter, The Johns Hopkins University. 159 pages, tables, paper, $1.25 ^9©^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Roberts Place, Ithaca, New York PROGRAM of the SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING of the American i|is!tor(cal Hsfsiociation December 28, 29, 30 1959 THE NAMES OF THE SOCIETIES MEETING \VITHIN OR JOINTLY WITH THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION ARE LISTED ON PAGE 47 ALLAN NFANNS Senior Research Associate, fluntinyton Library President of the American Historical Association The American Historical Association Officers Presidetit: Allan Nevins, Huntington Library Vice-President: Bernadotte E. -

Commencement 1941-1960

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE, MARYLAND Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the Seventy-Third Academic Year JUNE 14, 1949 GILMAN HALL TERRACE At Eleven A. M. ORDER OF PROCESSION CHIEF MARSHAL G. Hebebton Evans, Jr. Divisions Marshals 1. The President of the University, Sidney Painter the Chaplain, Honored Guests, the Trustees 2. The Faculty Thomas F. Hubbard 3. The Graduates Howard E. Cooper, Chief Henry T. Eowell Robert H. Roy Walter C. Boyer W. WORTHINGTON EWELL John M. Kopper Acheson J. Duncan N. Bryllion Fagin Richard H. Howland Gilbert F. Otto Barnett Cohen Charles A. Barker USHERS Chief Usher—Clyde W. Huether Allen Case Sloan Griswold Francis C. Chlan, Jr. John P. Lauber William B. Crane William M. Miller Charles E. Dalley John G. Schisler Brian L. DeVan Malcolm D. Voelcker ORGANIST John H. Eltermann The audience is requested to stand as the academic procession moves into the area and remain standing until after the Invocation. ORDER OF EXERCISES i UONJJ Grand March from "Sigurd Jorsalfar " by Grieg n [ntoc \ non The Reverend Clabb J. O'Dwyi u SS. Philip and James Church in Announcements and Qkebtings to Gbaduatbb President DetLEV W. Bronk IV Address to Graduates " " The Strength of Democracy Dr. Vannevar Bush v Conferring or Honorary Degrees Dr. Isaiah Bowman — presented by Mr. Owen Lattimore Dr. ABRAHAM Klexner — presented by Dr. H. Carrington Lancaster Dr. Alfred Newton Richards — presented by Dr. E. Kennerly Marshall, Jr. vi Conferring of Degrees Bachelors of Arts — presented by Dean Cox Bachelors of Engineering — presented by Dean Kouwenhoven Bachelors of Science in Engineering Masters of Science in Engineering Masters of Engineering Doctors of Engineering Bachelors of Science in Business — presented by Dean Hawkins Bachelors of Science — presented by Dean Horn Bachelors of Science in Nursing Masters of Education — presented by Professor Whitelaw Doctors of Education Masters of Science in Hygiene — presented by Dr. -

Commencement 1941-1960

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE, MARYLAND Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the Seventy-Eirst Academic Year JUNE 10, 1947 GILMAN HALL TERRACE At Eleven A. M. ORDER OF PROCESSION CHIEF MARSHAL G. Heberton Evans, Jr. Divisions Marshals 1. The President of the University, Sidney Painter the Chaplain, Honored Guests, the Trustees 2. The Faculty Francis H. Clatjser 3. The Graduates Howard E. Cooper, Chief Richard T. Cox John C. Geter Clarence D. Long Richard E. Thursfield W. Halsey Barker Gilbert F. Otto Henry T. Rowell USHERS U. Grant Peoples, Jr.—Chief Usher Gerald H. Cooper Daniel H. Levin John E. Feathers Ross Macaulay W. Noel Johnston Milton R. Roberts John I. Leopold Grant C. Vietsch ORGANIST John Varney The audience is requested to stand as the academic procession moves into the area and remain standing until after the Invocation. ORDER OF EXERCISES i Processional ii i \ \ ocation The Revereml W'n.i.iwi A. Kkkse Grace Methodist Church in Announcements and Greetings to Graduates The President of the University IV Presentation of The Alexander K. Barton Cup Presented by Dean G. Wilson Shaffer Borden Undergraduate Research Award in Medicine Presented by Dean Alan M. Chesney v Address to Graduates Owen Lattimoee Director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations VI Conferring of Honorary Degrees Announcements Concerning Recipients The President of the University Presentation of Candidates Dr. Joseph Erlanger — presented by Dr. Philip Baed Dr. Herbert S. Gasser — presented by Dr. E. Kennerly Marshall, Jr. Dr. Eugene L. Opie — presented by Dr. Arnold R. Rich Dr. George H. -

Appendix 1 the Family Connections of Joan De

APPENDIX 1 THE FAMILY CONNECTIONS OF JOAN DE VALENCE econstructing the lineages of these three groups can demonstrate Rhow very intertwined they were, both politically and socially. The children of William and Isabella Marshal married—or were mar- ried to—an interconnected and somewhat closed group of magnates and barons who were prominent either throughout the kingdom or in the specific localities of Marshal influence. The marriage strategies of the ultimate heirs to the Marshal estates mimicked those of their parents, even as the generations became more attenuated. William and Joan de Valence both reinforced these marriage patterns and introduced new ones, in particular by creating linkages with prominent barons in the North with ties to the Scottish throne. Isabella de Clare William Marshal d. 1220 M d. 1219 William Richard Gilbert Walter Anselm Maud Isabelle Sibyl Eva Joan d. 1231 d. 1234 d. 1241 d. 1245 d. 1245 d. 1248 d. 1240 d. ante-1245 d.1246 d.1234 m. m. m. m. m. m. m. m. m. m. 1) Alice de Bethune Gervaise de Dinan Marjorie of Scotland Margaret de Quency Maud de Bohun 1) Hugh Bigod 1) Gilbert de Clare William Ferrers William de Braose Warin de Munchensy 2) Eleanor Plantagenet wid. John de Lacy 2) William de Warenne 2) Richard of Cornwall Chart A1.1 The lineage of William Marshal and Isabella de Clare Maud Marshal Roger [dsp] m. Isabella of Scotland and Ralph [dsp] Hugh Bigod Maud m. Roger de Mortimer Hugh m. Joan de Stuteville (wid. Hugh Wake) Eva Marshal Eve m. William de Cantilupe and Isabel m.