Victory Awaits Him Who Has Everything in Order, Luck Some People Call It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide

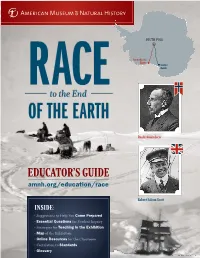

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN Voyage Handbook

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN voyage handbook MS ROALD AMUNDSEN VOYAGE HANDBOOK 20192020 1 Dear Adventurer 2 Dear adventurer, Europe 4 Congratulations on booking make your voyage even more an extraordinary cruise on enjoyable. Norway 6 board our extraordinary new vessel, MS Roald Amundsen. This handbook includes in- formation on your chosen Svalbard 8 The ship’s namesake, Norwe- destination, as well as other gian explorer Roald Amund- destinations this ship visits Greenland 12 sen’s success as an explorer is during the 2019-2020 sailing often explained by his thor- season. We hope you will nd The Northwest Passage 16 ough preparations before this information inspiring. departure. He once said “vic- Contents tory awaits him who has every- We promise you an amazing Alaska 18 thing in order.” Being true to adventure! Amund sen’s heritage of good South America 20 planning, we encourage you to Welcome aboard for the ad- read this handbook. venture of a lifetime! Antarctica 24 It will provide you with good Your Hurtigruten Team Protecting the Antarctic advice, historical context, Environment from Invasive 28 practical information, and in- Species spiring information that will Environmental Commitment 30 Important Information 32 Frequently Asked Questions 33 Practical Information 34 Before and After Your Voyage Life on Board 38 MS Roald Amundsen Pack Like an Explorer 44 Our Team on Board 46 Landing by Small Boats 48 Important Phone Numbers 49 Maritime Expressions 49 MS Roald Amundsen 50 Deck Plan 2 3 COVER FRONT PHOTO: © HURTIGRUTEN © GREGORY SMITH HURTIGRUTEN SMITH GREGORY © COVER BACK PHOTO: © ESPEN MILLS HURTIGRUTEN CLIMATE Europe lies mainly lands and new trading routes. -

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916 ‘BLUE PLAQUES’ adorn the houses of south polar explorers James Clark Ross, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, Sir Ernest H. Shackleton, and, at one time, Captain Laurence Oates (his house was demolished and the plaque stored away). If Sir Clements Markham had not lived, it’s not unreasonable to think that of these only the one for Ross would exist today. Markham was the Britain’s great champion of polar exploration, particularly Antarctic exploration. Markham presided over the Sixth International Geographical Congress in 1895, meeting in London, and inserted the declaration that “the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken.” The world took notice and eyes were soon directed South. Markham’s great achievement was the National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery 1901-04) for which he chose Robert Falcon Scott as leader. He would have passed on both Wilson and Shackleton, too. When Scott contemplated heading South again, it was Markham who lent his expertise at planning, fundraising and ‘gentle arm-twisting.’ Without him, the British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova 1910-13) might not have been. As a young man Markham was in the Royal Navy on the Pacific station and went to the Arctic on Austin’s Franklin Search expedition of 1850-51. He served for many years in the India Office. In 1860 he was charged with collecting cinchona trees and seeds in the Andes for planting in India thus assuring a dependable supply of quinine. He accompanied Napier on the Abyssinian campaign and was present at the capture of Magdala. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Roald Amundsen - First Man to Reach Both North and South Poles

Roald Amundsen - first man to reach both North and South Poles Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) was born to a shipowning family near Fredrikstad, Norway on July 16, 1872. From an early age, he was fascinated with polar exploration. He joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897, serving as first mate on the ship Belgica. When the ship was beset in the ice off the Antarctic Peninsula, its crew became the first to spend a winter in the Antarctic. First person to transit the Northwest Passage In 1903, he led a seven-man crew on the small steel-hull sealing vessel Gjoa in an attempt to traverse the fabled Northwest Passage. They entered Baffin Bay and headed west. The vessel spent two winters off King William Island (at a location now called Gjoa Haven). After a third winter trapped in the ice, Amundsen was able to navigate a passage into the Beaufort Sea after which he cleared into the Bering Strait, thus having successfully navigated the Northwest Passage. Continuing to the south of Victoria Island, the ship cleared the Canadian Arctic Archipelago on 17 August 1905, but had to stop for the winter before going on to Nome on the Alaska District's Pacific coast.before arriving in Nome, Alaska in 1906. It was at this time that Amundsen received news that Norway had formally become independent of Sweden and had a new king. Amundsen sent the new King Haakon VII news that it "was a great achievement for Norway". He said he hoped to do more and signed it "Your loyal subject, Roald Amundsen. -

Venture 2 Great Lives Video Worksheet Robert Falcon Scott

Venture 2 Great Lives Video worksheet Robert Falcon Scott Getting started 3 Complete the sentences with the names below. What do you know about the North and the Antarctic Scotland Royal Navy South Poles? Answer the questions: Shackleton South Africa Amundsen • Which pole is in the Arctic and which is in the 1 Scott was an officer in the . Antarctic? 2 The Discovery was built in . • What are the poles like? 3 Ernest was another famous explorer on • Have explorers been to both poles? When? Scott’s first expedition. Competences 4 The Discovery sailed south via . Check 5 Roald was the first person to reach the South Pole. 1 VIDEO Watch the video and choose the correct 6 Scott is known in the UK as ‘Scott of ’. answer. 1 The Discovery expedition went to the Antarctic Language check in 1901 to… A help another ship. 4 Use the prompts to write third conditional sentences. B fight a war. 1 If Scott (not hear) about the expedition, he (not C study nature. go) to the Antarctic. D find the South Pole. 2 Scott (could go) to the South Pole sooner if the 2 The scientists on the Discovery expedition… weather (be) better. A never reached the Antarctic. 3 If the Discovery (not be) so strong, the ice (might B didn’t survive the terrible weather. destroy) it. C couldn’t do their experiments. 4 Scott, Wilson and Shackleton (might reach) the South Pole if the conditions (not be) so bad. D had to wait to start their experiments. 5 If they (not have) dynamite, they (not free) the 3 Scott returned to the Antarctic in 1910 and… Discovery. -

Public Information Leaflet HISTORY.Indd

British Antarctic Survey History The United Kingdom has a long and distinguished record of scientific exploration in Antarctica. Before the creation of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), there were many surveying and scientific expeditions that laid the foundations for modern polar science. These ranged from Captain Cook’s naval voyages of the 18th century, to the famous expeditions led by Scott and Shackleton, to a secret wartime operation to secure British interests in Antarctica. Today, BAS is a world leader in polar science, maintaining the UK’s long history of Antarctic discovery and scientific endeavour. The early years Britain’s interests in Antarctica started with the first circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent by Captain James Cook during his voyage of 1772-75. Cook sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, into the pack ice reaching as far as 71°10' south and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time. He discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands although he did not set eyes on the Antarctic continent itself. His reports of fur seals led many sealers from Britain and the United States to head to the Antarctic to begin a long and unsustainable exploitation of the Southern Ocean. Image: Unloading cargo for the construction of ‘Base A’ on Goudier Island, Antarctic Peninsula (1944). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interest in Antarctica was largely focused on the exploitation of its surrounding waters by sealers and whalers. The discovery of the South Shetland Islands is attributed to Captain William Smith who was blown off course when sailing around Cape Horn in 1819. -

Santa Cruz Sentinel Columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz. #180 March 21, 2015 Shackleton’s Final Antarctic Adventure Captain Robert Scott and his Antarctic team in 1911 While Ernest Shackleton had at least temporarily settled down to a domestic life with his family in Sheringham, a seaside town on the southeast coast of England, others were undertaking their own Antarctic expeditions. Robert Falcon Scott and his four companions were in a race with Norwegian Roald Amundsen to be the first to reach the South Pole. Each team had taken a different route to the pole and was also using totally different strategies. Amundsen relied on his trusted sledge dogs to haul men and supplies over the ice. Scott, for some odd reason, thought horses would do better. The horses were poorly adapted to the extreme temperature, wind, and ice conditions, and died before long, leaving Scott and his men to haul their own sledges. Not a good start. Amundsen and his team reached the South Pole on December 14, 1911. A month later, under miserable conditions, Robert Scott and his four companions were making their final push to the pole, not realizing that Amundsen had already won the race. Scott’s journal reported temperatures down to 45 degrees below zero, nearly impassable terrain, and either blinding blizzards or blinding sunshine. They reached the pole on January 18, only to discover that the Norwegians has already arrived, left a flag and headed back to their own base. Disheartened and freezing, Scott and his men began the 800-mile trek back to their own ship and camp. -

Roald Amundsen Essay Prepared for the Encyclopedia of the Arctic by Jonathan M

Roald Amundsen Essay prepared for The Encyclopedia of the Arctic By Jonathan M. Karpoff No polar explorer can lay claim to as many major accomplishments as Roald Amundsen. Amundsen was the first to navigate a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the first to reach the South Pole, and the first to lay an undisputed claim to reaching the North Pole. He also sailed the Northeast Passage, reached a farthest north by air, and made the first crossing of the Arctic Ocean. Amundsen also was an astute and respectful ethnographer of the Netsilik Inuits, leaving valuable records and pictures of a two-year stay in northern Canada. Yet he appears to have been plagued with a public relations problem, regarded with suspicion by many as the man who stole the South Pole from Robert F. Scott, constantly having to fight off creditors, and never receiving the same adulation as his fellow Norwegian and sometime mentor, Fridtjof Nansen. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was born July 16, 1872 in Borge, Norway, the youngest of four brothers. He grew up in Oslo and at a young age was fascinated by the outdoors and tales of arctic exploration. He trained himself for a life of exploration by taking extended hiking and ski trips in Norway’s mountains and by learning seamanship and navigation. At age 25, he signed on as first mate for the Belgica expedition, which became the first to winter in the south polar region. Amundsen would form a lifelong respect for the Belgica’s physician, Frederick Cook, for Cook’s resourcefulness in combating scurvy and freeing the ship from the ice. -

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’S Earlier Voyages and Experience

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’s earlier voyages and experience. • Roald Amundsen joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–99) as first mate. • This expedition, led by Adrien de Gerlache using the ship the RV Belgica, became the first expedition to winter in Antarctica. Voyage in research vessel Belgica. • The Belgica, whether by mistake or design, became locked in the sea ice at 70°30′S off Alexander Island, west of the Antarctic Peninsula. • The crew endured a winter for which they were poorly prepared. • RV Belgica frozen in the ice, 1898. Gaining valuable experience. • By Amundsen's own estimation, the doctor for the expedition, the American Frederick Cook, probably saved the crew from scurvy by hunting for animals and feeding the crew fresh meat • In cases where citrus fruits are lacking, fresh meat from animals that make their own vitamin C (which most do) contains enough of the vitamin to prevent scurvy, and even partly treat it. • This was an important lesson for Amundsen's future expeditions. Frederick Cook с. 1906. Another successful voyage. • In 1903, Amundsen led the first expedition to successfully traverse Canada's Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. • He planned a small expedition of six men in a 45-ton fishing vessel, Gjøa, in order to have flexibility. Gjøa today. Sailing westward. • His ship had relatively shallow draft. This was important since the depth of the sea was about a metre in some places. • His technique was to use a small ship and hug the coast. Amundsen had the ship outfitted with a small gasoline engine. -

Amundsen & Scott

BIOGRAPHIES – Amundsen & Scott British Captain Robert Falcon Scott Born in 1868 in Devon, England, Scott became a Navy cadet at the then-customary age of 13. He was promoted to midshipman and, in 1889, to lieutenant. After his father died in 1897, leaving the family penniless, Scott became responsible for the welfare of his mother and unmarried sisters and needed a way to increase his income. Opportunity came in 1899, when Scott heard that the planned National Antarctic Expedition was in need of a commander. He won the post and undertook his first journey to Antarctica (1901-04), during which he and two other men, one of whom was Ernest Shackleton, travelled farther south than anyone had previously. On Scott’s return to Britain he was promoted to captain, allaying money worries. But he had unfinished business in the south. Scott married in 1908; the following September, the same month as the birth of his son Peter, Scott opened an office for the “British Antarctic Expedition (1910)” and began raising funds for a new expedition. Scott set sail for Antarctica, with the South Pole as his goal, in 1910 aboard his ship Terra Nova. Norwegian Explorer Roald Amundsen Born in 1872 into a prosperous family that ran a fleet of trading ships out of Christiania (now Oslo), Norway, Amundsen first dreamed of exploring at the age of 15 after reading about Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin, who had literally eaten boot leather to survive a particularly perilous expedition. In 1891, Amundsen enrolled in medical school to please his mother, but after his mother’s death in 1893 he began to pursue his dream of becoming a polar explorer.