The Port City of Chaul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nidān, Volume 4, No. 1, July 2019, Pp. 1-18 ISSN 2414-8636 1 The

Nidān, Volume 4, No. 1, July 2019, pp. 1-18 ISSN 2414-8636 The Cantonment Town of Aurangabad: Contextualizing Christian Missionary Activities in the Nineteenth Century Bina Sengar Assistant Professor, Department of History and Ancient Indian Culture School of Social Sciences Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, [email protected] Abstract The cantonment town of Aurangabad has a legacy of being soldier’s territory since the inception of the city of Aurangabad or Khadki/Fatehnagar in the late 13th century (Ramzaan, 1983, Green, 2009). The city’s settlement pattern evolved as per the requirements of cantonment, planned during the Nizamshahi and later, during the Mughal rule in the city. In fact, Aurangabad evolved as a cantonment city even before the British. As we study the city’s networks and its community history, we come across a civic society web, which gathered and settled gradually as service providers or as dependent social groups on the resident military force. In the late eighteenth century when the British allied with the Nizam state of Hyderabad, they were given special place in the Aurangabad cantonment to develop a military base. The British military base in the early decades of the nineteenth century in Aurangabad, thus, worked intensively to cope with the already well-established community connection of a strategic defence town. This research paper will explore and discuss relationships between British soldiers and officers and the well-established societal web of communities living in Aurangabad from early decades of nineteenth century, before the 1857 revolt. Keywords: Aurangabad, British, Cantonment, Defence, English Introduction During July 2018, army cantonments in India constituted the news headlines, and soon entered coffee table discussions among heritage lovers. -

Unit 9 the Deccan States and the Mugmals

I UNIT 9 THE DECCAN STATES AND THE MUGMALS Structure 9.0 Objectives I 9.1 Iiltroduction 9.2 Akbar and the Deccan States 9.3 Jahangir and the Deccan States 9.4 Shah Jahan and the Deccaa States 9.5 Aurangzeb and the Deccan States 9.6 An Assessnent of the Mughzl Policy in tie Deccan 9.7 Let Us Sum Up 9.8 Key Words t 9.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises -- -- 9.0 OBJECTIVES The relations between the Deccan states and the Mughals have been discussed in the present Unit. This Unit would introduce you to: 9 the policy pursued by different Mughal Emperors towards the Deccan states; 9 the factors that determined the Deccan policy of the Mughals, and the ultimate outcome of the struggle between the Mughals and the Deccan states. - 9.1 INTRODUCTION - In Unit 8 of this Block you have learnt how the independent Sultanates of Ahmednagar, Bijapur, Golkonda, Berar and Bidar had been established in the Deccan. We have already discussed the development of these states and their relations to each other (Unit 8). Here our focus would be on the Mughal relations with the Deccan states. The Deccan policy of the Mughals was not determined by any single factor. The strategic importance of the Decen states and the administrative and economic necessity of the Mughal empire largely guided the attitude of the Mughal rulers towards the Deccan states. Babar, the first Mughal ruler, could not establish any contact with Deccan because of his pre-occupations in the North. Still, his conquest of Chanderi in 1528 had brought the Mugllal empire close to the northern cbnfines of Malwa. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

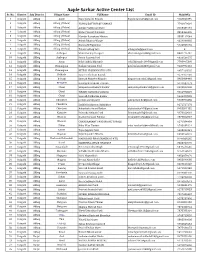

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

Malik Ambar.Docx

Malik Ambar Malik Ambar was a prime minister and general of African descent who served the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. He is regarded as a pioneer in guerilla warfare in the region along with being credited for carrying out a revenue settlement of much of the Deccan, which formed the basis for subsequent settlements. This article will give details about Malik Ambar within the context of the IAS Exam Early Life of Malik Ambar The man who would become Malik Ambar was born in 1548 in central Ethiopia. His birth name was Chapu. His people, the Oromo were relative newcomers in the region taking advantage of an ongoing war in the region to migrate. His childhood was typical of the Oromo people at the time - pastoralist and peaceful. 16the century Ethiopia was defined by slavery. While it impacted all communities, Solomonic Christian Kingdom and the Muslim Adal Sultanate targeted the largely spiritualist Oromo people when i came to slavery. By 1555 over 12,000 slaves per year were captured and sold in Ethiopia. Their destinations ranged from Cairo to the heart of Persia. Sure enough, at 12 years old Chapu was captured by Arabic traders, becoming a statistic in an epidemic slave trade that spread through the regions sorrounding the Indian Ocean. The young boy was put up in an auction in a slave market in a port on the coast of Yemen. Chapu was eventually sold to a merchant named Mir Qasim who took him to Baghdad. There, Qasim gave his slave an Arabic name - Ambar. He also taught him how to read, write and manage the finances of his masters business. -

MAHARASHTRA 799 © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely © Ajanta Ellora ( P825 )

© Lonely Planet Publications 799 Maharashtra Sprawling Maharashtra, India’s second most populous state, stretches from the gorgeous greens of the little-known Konkan Coast right into the parched innards of India’s beating heart. Within this massive framework are all the sights, sounds, tastes, and experiences of MAHARASHTRA MAHARASHTRA India. In the north there’s Nasik, a city of crashing colours, timeless ritual and Hindu legend. In the south you can come face to face with modern India at its very best in Pune, a city as famous for its sex guru as its bars and restaurants. Further south still, the old maharaja’s palaces, wrestling pits and overwhelming temples of Kolhapur make for one of the best introductions to India anyone could want. Out in the far east of the state towards Nagpur, the adventurous can set out in search of tigers hidden in a clump of national parks. On the coast a rash of little-trodden beaches and collapsing forts give Goa’s tropical dreams a run for their money and in the hills of the Western Ghats, morning mists lift to reveal stupen- dous views and colonial-flavoured hill stations. But it’s the centre, with its treasure house of architectural and artistic wonders (topped by the World Heritage–listed cave temples of Ellora and Ajanta), that really steals the show. Whatever way you look at it, Maharashtra is one of the most vibrant and rewarding corners of India, yet despite this, most travellers make only a brief artistic pause at Ellora and Ajanta before scurrying away to other corners of India, leaving much of this diverse state to the explorers. -

Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean 1St Edition Ebook

MALIK AMBAR: POWER AND SLAVERY ACROSS THE INDIAN OCEAN 1ST EDITION EBOOK Author: Omar H Ali Number of Pages: --- Published Date: --- Publisher: --- Publication Country: --- Language: --- ISBN: 9780190457181 Download Link: CLICK HERE Malik Ambar: Power And Slavery Across The Indian Ocean 1st Edition Online Read Part of The World in a Life series, this brief, inexpensive text provides insight into the life of slave soldier Malik Ambar. Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery across the Indian Ocean offers a rare look at an individual who began in obscurity in eastern Africa and reached the highest levels of South Asian political and military affairs in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Malik Ambar was enraged, went to court and killed the Sultan and his mother. Aroundnow in his early 20s, Ambar, as he was known, arrived in the Deccan where his long-time master sold him to the peshwa chief minister of Ahmadnagar. Your choices will not Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean 1st edition your visit. English By continuing to browse this site, you accept the use of cookies and similar technologies by our company as well as by third parties such as partner advertising agencies, allowing the use of data relating to the same user, in order to produce statistics of audiences and to offer you editorial services, an advertising offer adapted to your interests and the possibility of sharing content on social networks Enable. We invite you to discover more about this person and his heritage Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean 1st edition in a Facebook community. -

Aurangabad a Historical City of Deccan India

“Knowledge Scholar” An International Peer Reviewed Journal Of Multidisciplinary Research Volume: 01, Issue: 01, Nov. – Dec. 2014 eISSN NO. 2394-5362 AURANGABAD A HISTORICAL CITY OF DECCAN INDIA Syeda Amreen Sultana Dr. Abdullah Chaus M. A. 1 st Year History Lecturer Maulana Azad National Open University Dept. of History Maulana Azad Sub Centre Dr. Rafiq Zakaria College for Women Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. Introduction The history of Aurangabad , a city in Maharashtra, India, dates to 1610, when it was founded by Malik Ambar, the Prime Minister of Murtaza Nizam Shah ofAhmadnagar, on the site of a village called Kharki. In 1653 when Prince Aurangzeb was appointed the viceroy of the Deccan for the second time, he made Fatehnagar his capital and called it Aurangabad. Aurangabad is sometimes referred to as Khujista Bunyad by the Chroniclers of Aurangzeb's reign. History of the City Malik Ambar made it his capital and the men of his army raised their dwellings around it. Within a decade, Kharki g a populous and imposing city. Malik Ambar cherished strong love and ability for architecture. Aurangabad was Ambar's architectural achievement and creation. However, in 1621, it was ravaged and burnt down by the imperial troops under Jahangir. Ambar the founder of the city was always referred to by harsh names by Emperor Jahangir. In his memoirs, he never mentions his name without prefixing epithets http://www.ksijmr.com Page | 115 “Knowledge Scholar” An International Peer Reviewed Journal Of Multidisciplinary Research Volume: 01, Issue: 01, Nov. – Dec. 2014 eISSN NO. 2394-5362 like wretch, cursed fellow, Habshi, Ambar Siyari, black Ambar, and Ambar Badakhtur. -

YEARS of India Rebuilding

PM NAGPUR VISIT n DIALOGUE: CHIEF MINISTER n NITI AAYOG MEETING n ASIATIC SOCIETY VOL.6 ISSUE 05 n M AY 2017 n `50 n PAGES 52 YEARS OF REBUILDING INDIA PRIORITY Maharashtra A TRUSTED DESTINATION Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made all efforts to focus on the development of Maharashtra. The State has not just got support from him, but has also been a platform to launch and celebrate his initiatives 1 2 3 4 5 1. Prime Minister Narendra Modi performing jalpoojan of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj memorial; 2. The Prime Minister with Pune girl Vaishali Yadav; 3. The Prime Minister at the Make in India Week; 4. The Prime Minister with Governor Ch. Vidyasagar Rao, Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and other dignitaries at the Smart Cities function in Pune; 5. The Prime Minister inaugurates GE facility at Chakan; 6. The Prime Minister at the signing of MIDC and TwinStar Display Technologies MoU; 7. The Prime Minister performing bhoomipujan of Dr 6 Ambedkar memorial at Indu Mill 7 CONTENTS What’s Inside 05 Column DEVENDRA FADNAVIS The Chief Minister of Maharashtra writes on the three years of the Union Government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In these three years, the country has steadily transformed into a nation that is competent, enabled and fully geared to face challenges confidently and emerge as a global power. The time was also good for States like Maharashtra that recieved immense support, guidance, global opportunities and welfare programmes dedicated to various sections to build an inclusive society 09 COLUMN 12 COLUMN 14 COLUMN -

History ABSTRACT Politico-Administrative Developments in the Deccan Under Shahjahan

Research Paper Volume : 2 | Issue : 8 | AugustHistory 2013 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Politico-Administrative Developments in the KEYWORDS : Deccan, Shahjahan, Deccan Under Shahjahan Administration, Taqavi, Malik Ambar Lucky Khan Research Scholar (HISTORY), Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh ABSTRACT In the present paper an attempt has been made to analyse the political and administrative developments in the Deccan under the Emperor Shahjahan (1628-1658 A.D). The paper has been divided into two sections the first part deals with the political developments while the administration has been discussed in the second section. The Deccan however a different entity from that of the North India but attempts had always been made by the rulers to conquer it whether it was the Sultanate period or the Mughal rule. With the coming of the Mughals in the Deccan, the politico-administrative conditions of the Deccan had underwent certain changes according to the need of the time and in this paper I tried to discuss what has happened in the Deccan under Shahjahan. (I) The Political Scene: The pre-occupation of Jahangir in internal affairs after his ac- The Deccan literally means the southern and peninsular part of cession, failure of Mughal arms in the Deccan and the successes the great landmass of India. The Ramayana and Mahabharata of, Malik Ambar10 led Bijapur, the largest and best organized mention it as Dakshinapath. In describing this area the author state in the Deccan to change its attitude towards the Mughals. of Periplus also calls it Dakshinabades. In the Markandya, Vayu Ibrahim Adil Shah decided to ally himself with Malik Ambar in and Matsya Puranas the term Dakshina or Dakshinapath also trying to expel the Mughals from the territories they had seized denotes the whole peninsular south of the Narmada. -

Examining Slavery in the Medieval Deccan and in the Indian

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XIV APRIL 2012 FROM AFRICAN SLAVE TO DECCANI MILITARY AND POLITICAL LEADER: EXAMINING MALIK AMBAR’S LIFE AND LEGACY Author: Riksum Kazi Faculty Sponsor: Adam Knobler, Department of History ABSTRACT This paper examines the career of Malik Ambar (1549-1646). Originally an African slave soldier, he gained power in the regional politics of medieval India. Study of his life illustrates the dynamics, complexity, and politics of military slavery in the Deccan and India. INTRODUCTION Although fewer Africans were transported to the Indian subcontinent than to the Americas, they played a significant role in Indian history.1 Malik Ambar gained control of a sizable Deccani sultanate and transcended the traditional role of slave by resisting the Mughal Empire‘s armies and maintaining the socio- economic structure of the Deccan. Despite his accomplishments, Ambar he has been forgotten by historians for a variety of political, religious, and ethnic reasons. A note on terminology: in this paper, the word slave, unless otherwise indicated, connotes people of African heritage in involuntary servitude. The term Habshi refers to African slaves from the hinterlands of Ethiopia and the Sudan.2 THE DECCAN: GEOGRAPHIC BACKGROUND The Deccan, the principal geological region of Central India, is divided into five major areas: the Western Ghats, comprised of the Sahyadri range and coastal region near those mountains; the Northern Deccan plateau; the Southern Deccan plateau; the Eastern plateau; and the Eastern Ghats, including the Bengali coastal region. Its landscapes and climates vary from cold mountains to warm coastal plains.3 Moreover, the region was populated by speakers of Sanskrit, Tamil, Gujarati, Marathi, Persian, and Urdu and practicers of Hinduism and Islam. -

DIT Aple Sarkar Center Count.Xlsx

1 Raigad ALIBAG AGARSURE 2137 1 0 1 2 Raigad ALIBAG AKSHI 2976 1 0 1 3 Raigad ALIBAG AMBEPUR 5035 2 2 0 4 Raigad ALIBAG AWAS 4072 1 1 0 5 Raigad ALIBAG BAMANGAON 1815 1 1 0 6 Raigad ALIBAG BELKADE 777 1 1 0 7 Raigad ALIBAG BELOSHI 5748 2 2 0 8 Raigad ALIBAG BORGHAR 3614 1 0 1 9 Raigad ALIBAG BORIS 1220 1 0 1 10 Raigad ALIBAG CHARI 1894 1 0 1 11 Raigad ALIBAG CHENDHARE 9148 2 1 1 12 Raigad ALIBAG CHINCHAVALI 2652 1 0 1 13 Raigad ALIBAG CHINCHOTI 3539 1 0 1 14 Raigad ALIBAG CHAUL 10592 3 3 0 15 Raigad ALIBAG DHAVAR 1881 1 0 1 16 Raigad ALIBAG DHOKAWADE 3674 1 1 0 17 Raigad ALIBAG KAMARLE 3753 1 0 1 18 Raigad ALIBAG KAVIR 2434 1 0 1 19 Raigad ALIBAG KHANAV 5196 2 2 0 20 Raigad ALIBAG KHANDALE 4762 1 0 1 21 Raigad ALIBAG KHIDKI 636 1 0 1 22 Raigad ALIBAG KIHIM 4250 1 1 0 23 Raigad ALIBAG KOPROLI 3009 1 1 0 24 Raigad ALIBAG KURDUS 5942 2 0 2 25 Raigad ALIBAG KURKUNDI KOLTEEMBHI 1666 1 1 0 26 Raigad ALIBAG KURUL 5806 2 2 0 27 Raigad ALIBAG KUSUMBALE 4358 1 0 1 28 Raigad ALIBAG MAN(T) ZIRAD 3936 1 0 1 29 Raigad ALIBAG MANKULE 2805 1 1 0 30 Raigad ALIBAG MAPGAON 5307 2 2 0 31 Raigad ALIBAG MILKATKHAR 1475 1 0 1 32 Raigad ALIBAG MULE 862 1 0 1 33 Raigad ALIBAG NAGAON 6430 2 1 1 34 Raigad ALIBAG NARANGI 847 1 0 1 35 Raigad ALIBAG NAVEDAR NAVGAON 3962 1 0 1 36 Raigad ALIBAG PARHUR 3520 1 0 1 37 Raigad ALIBAG PEDHAMBE 1777 1 0 1 38 Raigad ALIBAG PEZARI 2114 1 0 1 39 Raigad ALIBAG POYNAD 4172 1 1 0 40 Raigad ALIBAG RAMRAJ 4614 1 1 0 41 Raigad ALIBAG RANJANKHAR DAWALI 1419 1 0 1 42 Raigad ALIBAG REVDANDA 9268 2 2 0 43 Raigad ALIBAG REWAS 1654 1 0 1