State of the Somerset Economy 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somerset. (Kblly's

SOMERSET. (KBLLY'S - Shepton Mallet; of silk at Taunton and Shepton Mallet; 4,932; Milborne Port, 1,630; Minehead, 3,458; Fortis horsehair seating at Castle Cary, Bruton and Crewkerne; head, 3,329; Radstock, 3,690; Shepton Mallet, s,ou; bruahes at Wella; of bricks, draining pipes and the cele Street, 4,235; Wellington, 7,633; Weston-super-Mare, brated Bath brick at Bridgwater, where are also extensive 23,235; Wincanton, 1,976; Wiveliscombe, 1,316; and coach building factories ; also manufactories ef spades, Axbridge with only 1,oo8. shovels and edge tools. This county contains 487 civil parishes, and with Upon the Avon are several mills for preparing iron and the exception of the parishes of Abbot'a Leigh and copper, and other& for spinning worsted and the spinning Bedminster and parts -of Maiden Bradley and Stourton, and weaving of cotton. is ep-extensive with the diocese of Bath and Wells, There are large breweries at Shepton Mallet and is within the province of C'antt'rbury, and divided Crewkerne. into the archdeaconrjes of Bath, Taunton and Wells, The chief mineral productions are coa.{ and free the first having no/ arC'hidiaconal court, and in the stone; fullers' earth (4,920 tons in 19u). Clay, otlier two latter the bishop exercising jurisdiction concur than fuller~' earth, was raised in 19II to the extent rently with the archdeacons ; Bath archdeaconry is of 92•793 tons, value [3,865. The stone which is divided into Bath deanery, sub-divided into the dis eommonly known by the name of Bath stone is quarried trict of Bath, Chew deanery sub-divided into the in thi~t county in 'the neighbourhood of Coombe Down districts of Chew Magna, Keynsham and Portishead ; and Meneton Coombe and in the adjoining district in Thnnton arohdeac1mry is divided into Bridgwater th& county of Wilts;' Ham Hill stone is found in this deanery, .sub-divided into the districts of Bridgwater county and Doulting stone both here and in Wilts. -

Bridgwater and Taunton Canal- Maunsel Lock to Creech St Michael

Bridgwater and Taunton Canal- Maunsel Lock to Creech St Michael (and return) Easy to Moderate Trail Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 8 miles Approximate Time: 2-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: Out and Back Waterways Travelled: Bridgewater and Taunton Canal Type of Water: Rural Canal Portages and Locks: 2 Nearest Town: Bridgewater/ Taunton Start and Finish: Maunsel Lock TA7 0DH O.S. Sheets: OS Map 182 Weston-Super-Mare OS Map Cutting in Bridgewater 193 Taunton and Lyme Regis Route Summary Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle Canoe along one of England’s best kept secrets. The on this waterway. See full details in useful information Bridgwater and Taunton Canal opened in 1827 and links below. the River Tone to the River Parrett. It is a well-kept secret Local Facilities: At the start and part way down the but a well-managed one! Local people, have set up a canal volunteer wardens scheme to look after their canal and their success can be shown in its beauty and peacefulness. This canal might be cut off from the rest of the system, but it has well-maintained towpaths and fascinating lock structures which make for idyllic walking and peaceful boating. -

Taunton Deane Edition

IS TH N Child Sexual IO IN IT Travel D Exploitation E SOMERSET pages Page 17 4&5 Volunteer drivers urgently wanted A day in the life of... pages 6&7 pages 14&15 Autumn 2016 Taunton Your Somerset Deane Keeping the county moving ore than £40m has been invested in Somerset’s roads in the last 18 months to keep the county moving and drive Mits economy forward. We’ve carried out a vast amount of work on schemes to reduce journey times, improve safety, support new housing developments and provide the transport network we need to help businesses thrive. More than £5m has been spent on major improvements to key roads and key junctions, including the Horsey and Hospital roundabouts in Yeovil and the Huntworth roundabout at junction 24 of the M5. A further £900,000 has gone into upgrading traffic signals, with big schemes in Taunton, Frome, Dunster and Bridgwater. More than £2m has been spent on nearly 40 Small Improvement Schemes across the county – community driven projects to tackle local highways problems. On top of that, we have invested over £30m in repairing and resurfacing the highway network. This vast programme of works has included the resurfacing of the A3088 Cartgate link road into Yeovil, the A30 in Chard and delivery of the largest surface dressing programme ever in Somerset. This represents a huge investment of capital funds (money we Congratulations to all Somerset can’t spend on the Council’s day-to-day running costs) in the county’s infrastructure. Even in these times of massive budget students who recently received pressures, making sure we have a quality road network is critical to the county’s future growth and prosperity. -

Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset

Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset A majestic Grade II listed country house in an accessible location and magical parkland setting with far reaching views over the Blackdown Hills to the south and the Quantock Hills to the north. Biomass heating and solar PV systems have been installed that generate an income to cover running costs. The property also has a Lodge which can further enhance this income through rental. Bishop’s Lydeard 4.4 miles, Taunton 9.4 miles (London Paddington 1 hour 40 minutes), Bristol Airport 40 miles, Exeter 40 miles (All mileages are approximate) Ground floor: Reception hall | Drawing room | Library | Dining room | Family sitting room| Winter garden room Kitchen / breakfast room| Pantry | Study | Home office| Coat / boot room | Flower room | Link to boiler house. Lift to all floors Lower ground floor: Home cinema | Store room | Cloakroom | Lobby | Wine cellar First floor: Master bedroom with dressing room and en suite bathroom| Two guest bedrooms with en suite bathrooms Four further bedrooms | Family bathroom | Laundry room | Linen room Second floor: Guest bedroom with en suite bathroom | Bedroom with dressing room | Two further bedrooms | Bathroom | Playroom Soundproof recording studio| Studio room / home office| Sitting room / bedroom 11| Three storage rooms The Lodge: Kitchen | Sitting room| Utility room | 3 bedrooms | Bathroom | Garden Outbuildings: Attached outbuilding with storage and cloakroom on ground floor and home office above Stable block with four loose -

Somerset County Council District of Sedgemoor

(Notice2) SOMERSET COUNTY COUNCIL DISTRICT OF SEDGEMOOR PARISHES OF BAWDRIP AND PURITON Temporary Closure of Glastonbury Road and Puriton Hill TAKE NOTICE that in pursuance of Section 14(1) of the Road Traffic Regulations Act 1984, as amended by the Road Traffic (Temporary Restrictions) Act 1991, the County Council of Somerset have made an Order PROHIBITING ALL TRAFFIC from proceeding along Glastonbury Road and Puriton Hill from Glastonbury Road; 20m southeast of the junction with Puriton Hill to Galstonbury Road to the junction with Puriton Hill and Puriton Hill; the junction with Glastonbury Road south-eastwards for 420m a total distance of 640 metres. This order will enable Somerset Highways to carry out resurfacing works in this road. The Order becomes effective on 28 April 2015 and will remain in force for eighteen months. The works are expected to last for 4 nights (19:00-07:00). While the closure is in operation an alternative route will be signed as detailed below. ALTERNATIVE ROUTE From the southern end of the closure proceed in south easterly and south westerly directions along the A39 to the junction with the A38. Turn right and proceed in north westerly and north easterly directions along the A38 to the junction with the A39. Turn right and proceed in north easterly and south easterly directions along the A39 to the northern end of the closure, and vice versa. Access to Puriton will be via the A39 and Riverton Road. For information about the works being carried out please contact Ron Chapman on 0845 345 9155 For further details of the alternative route please contact Somerset County Council on 0845 345 9155 Patrick Flaherty Chief Executive Dated: 23 April 2015 ihqiwyy syx2g fehs2g fshqei2 sry 2g fshqei qlstonury2od282uriton2rillD2 fwdrip gxiTVQU leX2222222222222222xot2o2le hrg2xoX gxiTVQU hteX22222222222222222PRGHQGIS hrwn2fyX sw E222glosure x E222hiversion E222rish2foundry ©2grown2gopyright2nd2htse2ight @PHISA yrdnne2urvey2IHHHQVQVP. -

SCC Covers (Page 1)

Somerset Local Transport Plan 2006-2011 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES - 1 15 Somerset Local Transport Plan 2006-2011 1 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES 1 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES Our vision for transport in Somerset builds upon the overarching community strategy 'vision' of the Somerset Strategic Partnership for 2025: Somerset Strategic Partnership Vision "A dynamic, successful, modern economy that supports, respects and develops Somerset's distinctive communities and unique environments". 1.1 TRANSPORT OBJECTIVES The National shared priorities for transport form the basis of our objectives for this LTP which are set out below. We have adopted environmental objectives to reflect Somerset’s unique landscape, heritage and biodiversity, and have also adopted economic objectives to reflect the regional priority for investment in our larger growth centres as well as the community strategy vision for economic regeneration. Improve safety for all who travel by meeting the following objectives: Reducing traffic accidents with a particular emphasis on killed and seriously injured casualties and rural main roads; and Reducing fear of crime in all aspects of the transport network. Reduce social exclusion and improve access to everyday facilities by meeting the following objectives: Improving access to work, learning, healthcare, food-shops and other services; Improving access to the countryside and recreation; and Facilitating the better co-ordination of activities of other authorities to improve accessibility of services. Reduce growth -

SCUDAMORE FAMILIES of WELLOW, BATH and FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440

Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, Bath & Frome, Somerset, from 1440 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKYDMORE/ SCUDAMORE FAMILIES OF WELLOW, BATH AND FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440. edited by Linda Moffatt ©2016, from the original work of Warren Skidmore. Revised July 2017. Preface I have combined work by Warren Skidmore from two sources in the production of this paper. Much of the content was originally published in book form as part of Thirty Generations of The Scudamore/Skidmore Family in England and America by Warren Skidmore, and revised and sold on CD in 2006. The material from this CD has now been transferred to the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com. Warren Skidmore produced in 2013 his Occasional Paper No. 46 Scudamore Descendants of certain Younger Sons that came out of Upton Scudamore, Wiltshire. In this paper he sets out the considerable circumstantial evidence for the origin of the Scudamores later found at Wellow, Somerset, as being Bratton Clovelly, Devon. Interested readers should consult in particular Section 5 of this, Warren’s last Occasional Paper, at the same website. The original text used by Warren Skidmore has been retained here, apart from the following. • Code numbers have been assigned to each male head of household, allowing cross-reference to other information in the databases of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study. Male heads of household in this piece have a code number prefixed WLW to denote their origin at Wellow. • In line with the policy of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study, details of individuals born within approximately the last 100 years are not placed on the Internet without express permission of descendants. -

SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS GUIDE 2016 COVER Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2

SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 1 SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2 Somerset Open Studios is a much-loved and thriving event and I’m proud to support it. It plays an invaluable role in identifying and celebrating a huge variety of creative activities and projects in this county, finding emerging artists and raising awareness of them. I urge you to go out and enjoy these glorious weeks of cultural exploration. Kevin McCloud Photo: Glenn Dearing “What a fantastic creative county we all live in!” Michael Eavis www.somersetartworks.org.uk SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS #SomersetOpenStudios16 SOS_GUIDE_2016_SB[2]_saw_guide 11/07/2016 09:58 Page 1 WELCOME TO OUR FESTIVAL! About Somerset Art Works Somerset Open Studios is back again! This year we have 208 venues and nearly 300 artists participating, Placing art at the heart of Somerset, showing a huge variety of work. Artists from every investing in the arts community, enriching lives. background and discipline will open up their studios - places that are usually private working environments, SAW is an artist-led organisation and what a privilege to be allowed in! Somerset’s only countywide agency dedicated to developing visual arts, Each year, Somerset Open Studios also works with weaving together communities and individuals, organisations and schools to develop the supporting the artists who enrich our event. We are delighted to work with King’s School lives. We want Somerset to be a Bruton and Bruton School for Girls to offer new and place where people expect to exciting work from a growing generation of artistic engage with excellent visual art that talent. -

Bridgwater Transport Options Forecast Report

BRIDGWATER TRANSPORT OPTIONS FORECAST REPORT October 2016 BRIDGWATER TRANSPORT OPTIONS FORECAST REPORT Somerset County Council Project no: 287584CQ-PTT Date: October 2016 WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff Riverside Chambers Castle Street Taunton TA1 4AP www.wspgroup.com www.pbworld.com iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PROJECT BACKGROUND ..........................................................1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES ............................................................. 1 1.3 MODELLING METHOD STATEMENT ............................................................ 2 1.4 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT ......................................................................... 2 2 FORECAST SCENARIOS ............................................................4 2.1 FORECAST YEARS ....................................................................................... 4 2.2 MODELLED SCENARIOS .............................................................................. 4 3 MODEL OVERVIEW .....................................................................6 3.1 MODEL HISTORY .......................................................................................... 6 3.2 TIME PERIODS .............................................................................................. 6 3.3 USER CLASSES ............................................................................................ 6 4 MODEL LINK VALIDATION .........................................................7 -

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

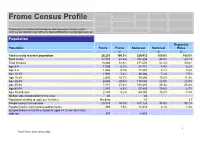

Frome Census Profile

Frome Census Profile Produced by the Partnership Intelligence Unit, Somerset County Council 2011 Census statistics from Office for National Statistics [email protected] Population England & Population Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % Total usually resident population 26,203 100.0% 529,972 100.0% 100.0% Total males 12,739 48.6% 258,396 48.8% 49.2% Total females 13,464 51.4% 271,576 51.2% 50.8% Age 0-4 1,659 6.3% 28,717 5.4% 6.2% Age 5-9 1,543 5.9% 27,487 5.2% 5.6% Age 10-15 1,936 7.4% 38,386 7.2% 7.0% Age 16-24 2,805 10.7% 54,266 10.2% 11.9% Age 25-44 6,685 25.5% 119,246 22.5% 27.4% Age 45-64 7,171 27.4% 150,210 28.3% 25.4% Age 65-74 2,247 8.6% 57,463 10.8% 8.7% Age 75 and over 2,157 8.2% 54,197 10.2% 7.8% Median age of population in the area 40 44 Population density (people per hectare) No data 1.5 3.7 People living in households 25,814 98.5% 517,124 97.6% 98.2% People living in communal establishments 389 1.5% 12,848 2.4% 1.8% Schoolchildren or full-time students aged 4+ at non term-time address 307 8,053 1 Frome Facts: 2011 census data Identity England & Ethnic Group Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % White Total 25,625 97.8% 519,255 98.0% 86.0% White: English/Welsh/Scottish/ Northern Irish/British 24,557 93.7% 501,558 94.6% 80.5% White: Irish 142 0.5% 2,257 0.4% 0.9% White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller 91 0.3% 733 0.1% 0.1% White: Other White 835 3.2% 14,707 2.8% 4.4% Black and Minority Ethnic Total 578 2.2% 10,717 2.0% 14.0% Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 57 0.2% 1,200 0.2% 0.8% Mixed: White and Black African 45 0.2% -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1 4DY J Roberts

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: Simon Butt County Hall FOI Reference: 1700165 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 3 November 2016 J Roberts ??? Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Would you be so kind as to please supply information regarding which public service bus routes within the Somerset Area are supported by funding subsidies from Somerset County Council. Our Response: I have listed the information that we hold below Registered Local Bus Services that receive some level of direct subsidy from Somerset County Council as at 1 November 2016 N8 South Somerset DRT 9 Donyatt - Crewkerne N10 Ilminster/Martock DRT C/F Bridgwater Town Services 16 Huish Episcopi - Bridgwater 19 Bridgwater - Street 25 Taunton - Dulverton 51 Stoke St. Gregory - Taunton 96 Yeovil - Chard - Taunton 162 Frome - Shepton Mallet 184 Frome - Midsomer Norton 198 Dulverton - Minehead 414/424 Frome - Midsomer Norton 668 Shipham - Street 669 Shepton Mallet - Street 3 Taunton - Bishops Hull 1 Bridgwater Town Service N6 South Petherton - Martock DRT 5 Babcary - Yeovil 8 Pilton - Yeovil 11 Yeovil Town Service 19 Bruton - Yeovil 33 Wincanton - Frome 67 Burnham - Wookey Hole 81 South Petherton - Yeovil N11 Yeovilton - Yeovil DRT 58/412 Frome to Westbury 196 Glastonbury Tor Bus Cheddar to Bristol shopper 40 Bridport - Yeovil 53 Warminster - Frome 158 Wincanton - Shaftesbury 74/212 Dorchester