Comprehending the Holocaust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

Whole Dissertation Hajkova 3

Abstract This dissertation explores the prisoner society in Terezín (Theresienstadt) ghetto, a transit ghetto in the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia. Nazis deported here over 140, 000 Czech, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Slovak, and Hungarian Jews. It was the only ghetto to last until the end of Second World War. A microhistorical approach reveals the dynamics of the inmate community, shedding light on broader issues of ethnicity, stratification, gender, and the political dimension of the “little people” shortly before they were killed. Rather than relegating Terezín to a footnote in narratives of the Holocaust or the Second World War, my work connects it to Central European, gender, and modern Jewish histories. A history of victims but also a study of an enforced Central European society in extremis, instead of defining them by the view of the perpetrators, this dissertation studies Terezín as an autarkic society. This approach is possible because the SS largely kept out of the ghetto. Terezín represents the largest sustained transnational encounter in the history of Central Europe, albeit an enforced one. Although the Nazis deported all the inmates on the basis of their alleged Jewishness, Terezín did not produce a common sense of Jewishness: the inmates were shaped by the countries they had considered home. Ethnicity defined culturally was a particularly salient means of differentiation. The dynamics connected to ethnic categorization and class formation allow a deeper understanding of cultural and national processes in Central and Western Europe in the twentieth century. The society in Terezín was simultaneously interconnected and stratified. There were no stark contradictions between the wealthy and majority of extremely poor prisoners. -

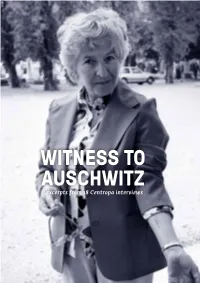

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire. -

Dr. Margalit Shlain. a Document Concerning Nazi Methods For

Dr. Margalit Shlain. A document concerning Nazi methods For deceiving Theresienstadt prisoners (Written 1991, rewritten June 2011) One of the primary elements used by the Germans in the mass murder of the Jews of Europe, within the frame of the "Final Solution", was the extensive spreading of the false information propaganda, deception and camouflage. The Nazi fake mechanism reached a unique peak in the establishment of Theresienstadt Ghetto (1941-1945), in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia, where nearly all the measures of deception were taken. At a meeting on October 10, 1941, of SS leaders of in Prague, led by SS Obergroupenfuehrer Heidrich, chief of Security Police and S.D. of the Reich, and acting SS Reichs Protector, it has been stated that : …certain concessions must be made due to the peculiar mentality of the Czech Jews, which differs from that prevailings in the General-Government in Poland. [1] In actual fact, from the outset, the Germans had planned that the Ghetto would be only a transit camp, for the Protectorate Jews, toward their deportation to the East. Outwardly Theresienstadt Ghetto was presented as a "Model Jewish Town". The purpose of which was: a) To deceive the Jews of the Protectorate and to ease their mind in order to gain their co-operation. b) To deceive international bodies by bringing their representatives to visit the Ghetto in order to put an end to the rumors circulating in the free world about mass murder of Jews in the "East". In order to satisfy certain circles inside Germany, the Nazis needed some pretext which signified that not all the Jews are murdered and that the "Final Solution" in general was carried out within some legal framework. -

Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1945

NAZI GERMANY AND THE JEWS, 1933–1945 ABRIDGED EDITION SAUL FRIEDLÄNDER Abridged by Orna Kenan To Una CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgments xiii Maps xv PART ONE : PERSECUTION (January 1933–August 1939) 1. Into the Third Reich: January 1933– December 1933 3 2. The Spirit of the Laws: January 1934– February 1936 32 3. Ideology and Card Index: March 1936– March 1938 61 4. Radicalization: March 1938–November 1938 87 5. A Broken Remnant: November 1938– September 1939 111 PART TWO : TERROR (September 1939–December 1941) 6. Poland Under German Rule: September 1939– April 1940 143 7. A New European Order: May 1940– December 1940 171 iv CONTENTS 8. A Tightening Noose: December 1940–June 1941 200 9. The Eastern Onslaught: June 1941– September 1941 229 10. The “Final Solution”: September 1941– December 1941 259 PART THREE : SHOAH (January 1942–May 1945) 11. Total Extermination: January 1942–June 1942 287 12. Total Extermination: July 1942–March 1943 316 13. Total Extermination: March 1943–October 1943 345 14. Total Extermination: Fall 1943–Spring 1944 374 15. The End: March 1944–May 1945 395 Notes 423 Selected Bibliography 449 Index 457 About the Author About the Abridger Other Books by Saul Friedlander Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher FOREWORD his abridged edition of Saul Friedländer’s two volume his- Ttory of Nazi Germany and the Jews is not meant to replace the original. Ideally it should encourage its readers to turn to the full-fledged version with its wealth of details and interpre- tive nuances, which of necessity could not be rendered here. -

By Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree in The

THE ROLE OF MUSIC, PERFORMING ARTISTS AND COMPOSERS IN GERMAN-CONTROLLED CONCENTRATION CAMPS AND GHETTOS DURING WORLD WAR II by WILLEM ANDRE TOERIEN submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree M MUS (Musicology) in the Faculty of Arts UNIVERSITY OF 'PRETORIA Supervisor: DR H H VAN DER MESCHT PRETORIA October 1993 © University of Pretoria Krechtst nisht, shrayt nisht, zingt a lid. Don't moan, don't cry, sing a song. Line from a song by Emanuel Hirshberg, an inmate of the Lodz ghetto (Rubin 1963:432) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following persons who helped me in one way or another: The help I received from the staff of the libraries of the University of Pretoria, University of South Africa (Pretoria) and the Zionist Federation (Johannesburg) was invaluable. I wish to thank my Study Supervisor, Dr van der Mescht, for his great interest in the topic I decided on, and the hours he spent working with me. My parents deserve special mention for their encouragement, and the hours they put into the editing and proof-reading of my work. The advice they gave was worth a lot to me. I would further like to thank my wife, Yvonne, for the encouragement and help she provided in so many ways, despite her own busy schedule. She was always there to listen to what I had written, and helped me proof-read and type this dissertation. Most of all I need to thank my Heavenly Father who carried me through the period of research. His encouragement brought me through the times of doubt and uncertainty. -

Terezin Resources

Terezin Resources Websites Theresienstadt. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?ModuleId=10005424 The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum describes the three main functions of the ghetto and explains how the Nazis were able to deceive the rest of the world regarding their treatment of the Jews. Terezin (Theresienstadt) Concentration Camp. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/terezin.html The Jewish Virtual Library tells the story of Terezin from its creation in 1780 to serve as a fortress protecting Prague from invaders to the “city built for the Jews.” Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. http://www1.yadvashem.org/education/terezin/eng/lexicon.htm Yad Vashem offers a glossary of terms associated with the Terezin ghetto, a timeline associated to Hitler’s takeover of Terezin, a picture gallery collected from the Terezin ghetto, a lesson plan for teachers, and additional materials of interest to educators. Virtual Tour of Theresienstadt. http://history1900s.about.com/library/holocaust/aa012599.htm This virtual tour of Theresienstadt shows the ghetto room by room and explains the purpose for each room. Books Berkley, George E. Hitler's Gift: The Story of Theresienstadt. Boston: Branden Books, 1993. Bondy, Ruth. "Elder of the Jews": Jakob Edelstein of Theresienstadt. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Bor, Josef. The Terezin Requiem. New York: Knopf, 1963. Brenner, Hannelore. The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope, and Survival in Theresienstadt. Schocken. 2009. Friedman, Saul S., ed. The Terezin Diary of Gonda Redlich. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992. Friesova, Jana Renee. Fortress of My Youth: Memoir of a Terezín Survivor. -

The Fortress Town of Terezin, Situated About from Prague in What Is Now the Czech Republic, Became, in 19 Thereisens

Miriam Intrator. Avenues of Intellectual Resistance in the Ghetto Theresienstadt: Escape Through the Ghetto Central Library, Reading, Storytelling and Lecturing. A Master’s paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2003. 97 pages. Advisor: David Carr The Ghetto Theresienstadt served as a façade behind which the Nazis attempted to hide the atrocities they were committing in other ghettos and concentration camps throughout Europe. As a result of its unusual nature, the Nazis sanctioned certain cultural and intellectual activities in the camp. Consequently, there remains a considerable record of the interior lives and personal perspectives of Theresienstadt inmates. Through a close examination of thirty-one Theresienstadt memoirs, diaries and histories, this paper explores the concept of intellectual resistance as a result of participation in some of the camp’s intellectual activities - the library, books, reading, storytelling and lecturing. These activities provided prisoners with a means of keeping their minds and imaginations active and alive, allowing them to temporarily escape from the horror surrounding them, and to maintain hope and strength that would help them to survive. As of yet, no single work in English focuses on this topic. This paper strives to fill that void and to encourage librarians to consider the power of literacy and the significance of their responsibilities, particularly in times of terror or war. Headings: Theresienstadt (Concentration camp) Theresienstadt (Concentration camp) – Literary Collections Holocaust, -

Jewish Flight from the Bohemian Lands, 1938-1941

NETWORKS OF ESCAPE: JEWISH FLIGHT FROM THE BOHEMIAN LANDS, 1938-1941 Laura E. Brade A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Christopher R. Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch Donald Raleigh Susan Pennybacker Karen Auerbach © 2017 Laura E. Brade ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Laura E. Brade: Networks of Escape: Jewish Flight from the Bohemian Lands, 1938- 1941 (Under the direction of Christopher R. Browning and Chad Bryant) This dissertation tells the remarkable of a quarter of the Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia who managed to escape Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia between October 1938 and October 1941. Given all of the obstacles to emigration—an occupation government, a world war, international reluctance to grant visas, and extortionist Nazi emigration policies—this amounted to an extraordinary achievement. Czechoslovak Jews scattered across the globe, from Shanghai and India, to Madagascar and Ecuador. How did they accomplish this daunting task? The current scholarship has approached this question from the perspectives of governments, voluntary organizations, and individual refugees. However, by addressing the various actors in isolation, much of this research has focused either on condemning or heroizing these actors. As a result, the question of how Jewish refugees fled Europe has gone unanswered. Using the Bohemian Lands as a case study, I ask when and how rescue became possible. I make three major claims. First, I argue that a grassroots transnational network of escape facilitated leaving Nazi-occupied Europe. -

Ghettos Bibliography

Ghettos Bibliography Books Adelson, Alan and Robert Lapides. Lodz Ghetto: Inside a Community Under Siege. Penguin Books: New York, 1989. Arad, Yitzhak. Ghetto in Flames: The Struggle and Destruction of the Jews in Vilna in the Holocaust. Yad Vashem, Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority: New York, 1981. Bondy, Ruth. “Elder of the Jews:” Jakob Edelstein of Theresienstadt. Grove Press: New York, 1989. Cole, Tim. Holocaust City. Routledge: New York, 2003. De Silva, Cara. In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezin. J. Aronson: Northvale, NJ, 1996 Dobroszycki, Lucjan. The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto: 1941-1944. Yale University Press: New Haven, 1984 Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston: New York, 1986. Hilberg, Raul ed. The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow: Prelude to Doom. Ivan R. Dee, in association with the USHMM: Chicago, 1999. Katsh, Abraham. Scroll of Agony: The Warsaw Diary of Chaim A. Kaplan. Macmillan: New York, 1965. Keller, Ulrich. The Warsaw Ghetto in Photographs. Dover Publications: New York, 1984. Korczak, Janusz. Ghetto Diary. Yale University Press: London, 2003. Kruk, Herman. The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania: Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939-1944. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research: New Haven, CT, 2002. Lifton, Betty Jean. The King of Children: A Biography of Janusz Korczak. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 1988. Meed, Vladka. On Both Sides of the Wall: Memoirs from the Warsaw Ghetto. Holocaust Library: New York, 1993. Niewyk, Donald. Fresh Wounds: Early Narratives of Holocaust Survival. -

Dapeykesher-52-2002-01-English

Beit Theresienstadt and the Theresienstadt Martyrs Remembrance Association Congratulates the CONFERENCE ON JEWISH MATERIAL CLAIMS AGAINST GERMANY, INC To its fiftieth anniversary! Thanks for your support and cooperation Number 52 January 2002 IN THIS ISSUE: page page Appreciation 2 Our Archives 11 In Memoriam 2 Music 16 Activities at Beit Terezin 4 Books and Publications 17 Second Generation 7 Press and Internet 20 Our Educational Center 7 Information Requested - Announcements 22 Student’s and Pupil’s Papers 9 Readers Letters 23 Financial Matters 9 Membership Dues 24 Actualities 10 2 APPRECIATION Fiftieth Anniversary of the Claims Conference In 2001 the CONFERENCE ON JEWISH MATERIAL CLAIMS AGAINST GERMANY had its fiftieth anniversary – it is the body representing the Jewish world in all matters of restitution and other claims against Germany. On this occasion a festive ceremony was held at Yad Vashem on November 27, 2001. Yad Vashem, Lohamei Hagetaot, Massuah and Moreshet initiated the ceremony. Beit Theresienstadt joins in the appreciation and in the wishes for a further fruitful activity of the Claims Conference in Israel and the world over. Today the Claims Conference has a key position in all new contracts concerning the German foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” regarding slave labour, forced labour, the Swiss program for refugees, the agreement with the Swiss banks and payments of insurance companies. According to its web site the Claims Conference achieved in the 50 years a great deal: More than 500,000 Holocaust survivors in 67 countries have received compensation payments as a result of the work of the Claims Conference. Payments to Holocaust survivors as a result of the work of the Claims Conference have come to more than DM 100 billion The Claims Conference has allocated more than $500 million to organizations meeting the social service needs of Holocaust survivors and engaging in education, research, and documentation of the Shoah. -

Unbroken Will to Live the Power of Spiritual Resistance in the Theresienstadt Ghetto

Unbroken Will to Live The Power of Spiritual Resistance in the Theresienstadt Ghetto AUTHOR: Tianna Voort EDITED BY: Eli Feldman, Esti Azizi, and Marisa Coulton Life in the Theresienstadt ghetto was distinct is a Hebrew word that translates to ‘stand.’ The from the rest of the ghettos established in Nazi- term Amidah encompasses all Jewish expressions occupied Europe. The Nazis used Theresienstadt of non-conformism, which were intended to oppose as a form of propaganda to masquerade their the Nazis’ goal to dehumanize and deprive the inhumane treatment of the Jews, calm the Jews of their humanity. In the ghettos, the Jews’ fears of the international community, and draw ability to resist German efforts of dehumanization attention away from their creation of death camps demonstrated immense courage and heroism of throughout Eastern Europe. Famous Jews were the spirit.1 Jews in the ghetto did not passively sent to Theresienstadt from 1941-1944, which led accept their fates; instead, they lived their lives as to a disproportionate number of cultural elite in human beings with hope for a better future, and the ghetto. The Nazis’ plan to use Theresienstadt showed the Nazis that they could not succeed in as a model ghetto allowed for the development destroying their humanity or dignity. In the face of a distinct and fourishing cultural life, which of dire suffering, the creation of cultural activities included music, opera, theatre, art exhibitions, represented an essential means of spiritual poetry, lectures, and literature. Importantly, such resistance against the Nazis’ desire to destroy prosperous cultural life became a form of spiritual Jewish humanity.