Don't Put All Your Emotional Eggs in Prospects' Future Baskets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Baseball No

UCLA Baseball No. 20 UCLA (33-26) vs. No. 25 Cal State Fullerton (36-23) 2007 NCAA Super Regionals Goodwin Field (3,500) – Fullerton, Calif. – June 9-11 BRUINS OFF TO SUPER REGIONALS 2007 SCHEDULE UCLA won the Long Beach Regional with wins over Pepperdine, Horizon League Champion Illinois- 2/2 #23 Winthrop W, 2-1 Chicago and Long Beach State. The Bruins have advanced to the NCAA Super Regionals for the first 2/3 #23 Winthrop L, 6-4 time since 2000 and will play a best-of-three series at Cal State Fullerton. Currently ranked No. 20 by 2/4 #23 Winthrop W, 19-5 Baseball America, UCLA has moved past the regional round four times – 1969, 1997, 2000 and 2007. 2/9 at #5 Miami L, 1-0 2/10 at #5 Miami L, 9-8 UCLA advanced to the Long Beach Regional as a No. 2 seed after finishing third in the Pac-10. 2/11 at #5 Miami L, 7-3 2/13 UC Riverside W, 3-2 PROBABLE STARTERS 2/16 East Carolina W, 6-1 Game 1 UCLA – Tyson Brummett, RHP (10-5, 3.57) vs. Cal State Fullerton – Wes Roemer, RHP (10-6, 3.33) 2/17 East Carolina W, 9-7 Game 2 UCLA – Gavin Brooks, LHP (6-6, 4.65) vs. Cal State Fullerton – Jeff Kaplan, RHP (11-3, 3.35) 2/18 East Carolina W, 7-6 Game 3 UCLA – TBA vs. Cal State Fullerton – TBA 2/20 at #20 Long Beach State L, 14-1 2/23 at #10 Cal State Fullerton W, 6-2 ON THE AIR 2/24 #10 Cal State Fullerton L, 7-4 UCLA’s Super Regional action will be broadcast live on ESPN (Saturday) and ESPN2 (Sunday and 2/25 #10 Cal State Fullerton L, 7-2 Monday). -

Central Times

Central Times Volume 2 No. 9 CTO Staff: Samantha Gottlieb Nikki Greenberg The First World Baseball Classic Alan Hendel The World Baseball Classic features many of the best MLB Nico Landgraf players around the world. The contestants play for their home Zach Mandell country to see which world team has the best talent. The men are Lauren Olswanger chosen by the Major League Baseball (MLB) and the Major League Sam Peregrine Baseball Players Association (MLBPA). The following countries Andrea Rubens will participate: Australia, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, Cuba, Sarah Smith Dominican Republic, Italy, Netherlands, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Jordan Stern Panama, Puerto Rico, South Africa, United States, and Venezuela. Ryan Streur Up to 30 players may participate on a team and if the player is currently in spring training, they will leave to practice with their Jason Abrams world team. Eleanor Black Emilie Bold Josh Brass Brandon Butz Etienne Colon- Japan won Berlingeri the World Elizabeth Cooney Classic and Nick DiLeonardi now is the Jonny Ginsburg first ever Matt Graller champion of Caiti Kengott a world Lexa Peterson competition Gavin Taves in baseball. Emily Tumen The final Hilary Weinstein score of the Holly West game was Jamie Chudacoff Japan: 10, Faculty Advisor: and Cuba: 6. Mrs. Dalleska 1 BY: JULIA PERELMAN AND SAMANTHA GOTTLIEB WHAT ARE THE TWO PICTURES IN THIS COLLAGE? ANSWER: SUNSET AND FIREWORKS AND SUNSET ANSWER: 2 Cards vs Cubs By Jordan Stern With the regular season approaching the MLB teams are getting ready for opening day. The Cubs vs Cardinals is one of the many great openers. -

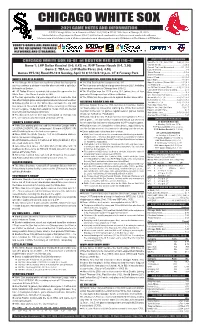

CHICAGO WHITE SOX GAME NOTES Chicago White Sox Media Relations Departmentgame 333 W

CHICAGO WHITE SOX GAME NOTES Chicago White Sox Media Relations DepartmentGAME 333 W. 35th StreetN Chicago,OTES IL 60616 Phone: 312-674-5300 Fax: 312-674-5847 Director: Bob Beghtol, 312-674-5303 Manager: Ray Garcia, 312-674-5306 Coordinators: Leni Depoister, 312-674-5300 and Joe Roti, 312-674-5319 © 2013 Chicago White Sox whitesox.com orgullosox.com whitesoxpressbox.com mlbpressbox.com Twitter: @whitesox CHICAGO WHITE SOX (56-81) at NEW YORK YANKEES (74-64) WHITE SOX BREAKDOWN Record ..............................................56-81 RHP Erik Johnson (MLB Debut) vs. LHP CC Sabathia (12-11, 4.91) Sox After 137/138 in 2012 ..... 74-63/75-63 Current Streak .................................Lost 5 Current Trip ...........................................0-5 Game #138/Road #72 Wednesday, September 4, 2013 Last Homestand ....................................4-2 Last 10 Games .....................................4-6 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. NEW YORK-AL Series Record ............................... 16-21-7 First/Second Half ................... 37-55/19-26 The Chicago White Sox have lost fi ve straight games as they The White Sox lead the season series, 3-2, and need one win Home/Road ............................ 32-34/24-47 continue a 10-game trip tonight with the fi nale in New York … to clinch their second consecutive season series victory over the Day/Night ............................... 22-27/34-54 RHP Erik Johnson, whose contract was purchased from Class Yankees, a feat they last accomplished from 1993-95. Grass/Turf .................................. 54-76/2-5 AAA Charlotte yesterday, takes the mound for the White Sox. Chicago’s six-game winning streak against New York ended Opp. Above/At-Below .500 .... -

SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 2016 at NEW YORK YANKEES LH Blake Snell (ML Debut) Vs

SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 2016 at NEW YORK YANKEES LH Blake Snell (ML Debut) vs. RH Mashiro Tanaka (1-0, 3.06) First Pitch: 1:05 p.m. | Location: Yankee Stadium, Bronx, N.Y. | TV: Fox Sports Sun | Radio: WDAE 620 AM, WGES 680 AM (Sp.) Game No.: 17 (7-9) | Road Game No.: 7 (2-4) | All-Time Game No.: 2,931 (1,359-1,571) | All-Time Road Game No.: 1,462 (610-851) RAY MATTER—The Rays opened this series with a 6-3 loss last night, the for-112) in the 8th or later and .210 (87-for-414) in innings 1-through-7… AL-high 12th time they have been to 3 runs or fewer (3-9)…the Rays are 4-0 the Rays have gone into the 7th inning stretch with a lead only three times. when they score more than 3 runs…22 pct. of the Rays runs this season came in one game, Thursday’s 12-8 win at Boston…Tampa Bay is 2-2 on vs. THE A.L. BEASTS—The Rays ($57M payroll) are on a 6-game road trip this 6-game trip (2-1 at Boston and 0-1 here)…Rays have won their last two to face the Red Sox ($191M payroll) and the Yankees ($222M payroll)…since series and are 4-2 in their last 6 games…they are 7-9 for the second time in 2010, the Rays are 61-53 vs. the Red Sox and 59-53 vs. the Yankees…their the past three years…they were 8-8 a year ago…this trip starts the Rays on a 120-106 record is the AL’s best combined record vs. -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Baseball Record Book

2018 BASEBALL RECORD BOOK BIG12SPORTS.COM @BIG12CONFERENCE #BIG12BSB CHAMPIONSHIP INFORMATION/HISTORY The 2018 Phillips 66 Big 12 Baseball Championship will be held at Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark, May 23-27. Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark is home to the Los Angeles Dodgers Triple A team, the Oklahoma City Dodgers. Located in OKC’s vibrant Bricktown District, the ballpark opened in 1998. A thriving urban entertainment district, Bricktown is home to more than 45 restaurants, many bars, clubs, and retail shops, as well as family- friendly attractions, museums and galleries. Bricktown is the gateway to CHAMPIONSHIP SCHEDULE Oklahoma City for tourists, convention attendees, and day trippers from WEDNESDAY, MAY 23 around the region. Game 1: Teams To Be Determined (FCS) 9:00 a.m. Game 2: Teams To Be Determined (FCS) 12:30 p.m. This year marks the 19th time Oklahoma City has hosted the event. Three Game 3: Teams To Be Determined (FCS) 4:00 p.m. additional venues have sponsored the championship: All-Sports Stadium, Game 4: Teams To Be Determined (FCS) 7:30 p.m. Oklahoma City (1997); The Ballpark in Arlington (2002, ‘04) and ONEOK Field in Tulsa (2015). THURSDAY MAY 24 Game 5: Game 1 Loser vs. Game 2 Loser (FCS) 9:00 a.m. Past postseason championship winners include Kansas (2006), Missouri Game 6: Game 3 Loser vs. Game 4 Loser (FCS) 12:30 p.m. (2012), Nebraska (1999-2001, ‘05), Oklahoma (1997, 2013), Oklahoma Game 7: Game 1 Winner vs. Game 2 Winner (FCS) 4:00 p.m. State (2004, ‘17), TCU (2014, ‘16), Texas (2002-03, ‘08-09, ‘15), Texas Game 8: Game 3 Winner vs. -

Sweet Perfection Preserve Baseball History

www.pgcitizen.ca | Friday, July 24, 2009 11 sports Ninth-inning heroics Sweet perfection preserve baseball history The Associated Press CHICAGO — The 105th pitch of Mark Buehrle’s day broke in toward Gabe Kapler, who turned on it and connected. Buehrle looked up and knew - his perfect game was in jeopardy. Just in as a defensive replacement, Chica- go White Sox centre fielder DeWayne Wise sprinted toward the fence in left-centre, a dozen strides. What happened next would be either a moment of baseball magic or the ninth-inning end of Buehrle’s bid for perfec- tion against the Tampa Bay Rays. Wise jumped and extended his right arm above the top of the wall. The ball landed in his glove’s webbing but then popped out for a split second as he was caroming off the wall and stumbling on the warning track. Wise grabbed it with his bare left hand, fell to the ground and rolled. He bounced mondbacks pitched a perfect game. So I’ve up, proudly displaying the ball for the been on both sides of it,” he said. “It was crowd. probably the best catch I’ve ever made be- Magic. A home run turned into an out. cause of the circumstances. His biggest threat behind him, Buehrle “It was kind of crazy, man, because when closed out the 18th perfect game in major I jumped, the ball hit my glove at the same league history, a 5-0 victory Thursday. time I was hitting the wall. So I didn’t real- “I was hoping it was staying in there, give ize I had caught it until I fell down and the him enough room to catch it. -

White Sox Game Notes

CHICAGO WHITE SOX 2021 GAME NOTES AND INFORMATION © 2021 Chicago White Sox Guaranteed Rate Field (1991) 333 W. 35th Street Chicago, Ill. 60616 Media Relations Department Phone: 312-674-5300 Email: [email protected] credentials.mlb.com whitesox.com loswhitesox.com whitesoxpressbox.com chisoxpressbox.com @whitesox @loswhitesox #WhiteSox TODAY'S GAMES ARE AVAILABLE ON THE FOLLOWING TV/RADIO NETWORKS AND STREAMING: WHITE SOX 2021 BREAKDOWN CHICAGO WHITE SOX (6-8) at BOSTON RED SOX (10-4) Sox after 14 | 15 | 16 in 2020 .......8-6 | 8-7 | 8-8 Current Streak ......................................... Lost 2 Game 1: LHP Dallas Keuchel (0-0, 6.43) vs. RHP Tanner Houck (0-1, 3.00) Current Trip | Last Homestand .............0-1 | 3-3 Game 2: TBA vs. LHP Martin Pérez (0-0, 4.50) Last 10 Games .............................................4-6 Series Record ............................................1-1-2 Games #15-16 | Road #9-10 Sunday, April 18 12:10/4:10 p.m. CT Fenway Park Series First Game.........................................3-2 Home | Road ........................................3-3 | 3-5 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. BOSTON RED SOX Day | Night ............................................1-4 | 5-4 The Chicago White Sox have lost three of their last four games The Red Sox lead the season series, 1-0. Opp. At or Above | Below .500 ..............6-7 | 0-1 as they continue a six-game trip this afternoon with a split dou- The teams are scheduled to play seven times in 2021, including vs. RHS | LHS ......................................3-7 | 3-1 bleheader at Boston. a three-game series in Chicago from 9/10-12. -

Mediaguide.Pdf

American Legion Baseball would like to thank the following: 2017 ALWS schedule THURSDAY – AUGUST 10 Game 1 – 9:30am – Northeast vs. Great Lakes Game 2 – 1:00pm – Central Plains vs. Western Game 3 – 4:30pm – Mid-South vs. Northwest Game 4 – 8:00pm – Southeast vs. Mid-Atlantic Off day – none FRIDAY – AUGUST 11 Game 5 – 4:00pm – Great Lakes vs. Central Plains Game 6 – 7:30pm – Western vs. Northeastern Off day – Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Mid-South, Northwest SATURDAY – AUGUST 12 Game 7 – 11:30am – Mid-Atlantic vs. Mid-South Game 8 – 3:30pm – Northwest vs. Southeast The American Legion Game 9 – Northeast vs. Central Plains Off day – Great Lakes, Western Code of Sportsmanship SUNDAY – AUGUST 13 Game 10 – Noon – Great Lakes vs. Western I will keep the rules Game 11 – 3:30pm – Mid-Atlantic vs. Northwest Keep faith with my teammates Game 12 – 7:30pm – Southeast vs. Mid-South Keep my temper Off day – Northeast, Central Plains Keep myself fit Keep a stout heart in defeat MONDAY – AUGUST 14 Game 13 – 3:00pm – STARS winner vs. STRIPES runner-up Keep my pride under in victory Game 14 – 7:00pm – STRIPLES winner vs. STARS runner-up Keep a sound soul, a clean mind And a healthy body. TUESDAY – AUGUST 14 – CHAMPIONSHIP TUESDAY Game 15 – 7:00pm – winner game 13 vs. winner game 14 ALWS matches Stars and Stripes On the cover Top left: Logan Vidrine pitches Texarkana AR into the finals The 2017 American Legion World Series will salute the Stars of the ALWS championship with a three-hit performance and Stripes when playing its 91st World Series (92nd year) against previously unbeaten Rockport IN. -

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book Table of Contents Lugnuts Media Guide Staff Directory ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Executive Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Midwest League Midwest League Map and Affiliation History .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bowling Green Hot Rods / Dayton Dragons ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Fort Wayne TinCaps / Great Lakes Loons ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Lake County Captains / South Bend Cubs ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 West Michigan Whitecaps ............................................................................................................................................................................................