NUMBER K2 .- WHORF, BENJAMIN LEE a CONTRIBUTION to the STUDY of the AZTEC LANGUAGE. 1928

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

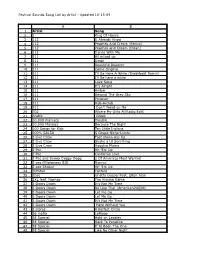

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Hdnet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012

HDNet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012 Monday January 30, 2012 3:30 PM ET / 12:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT HDNet Fights Visions of New York City DREAM New Year! 2011 - Former PRIDE Heavyweight Champion Fedor Emelianenko meets New York in all its striking juxtapositions of nature and modern progress, geometry and geog- Olympic Judo Gold Medalist Satoshi Ishii. Shinya Aoki defends the DREAM Lightweight Title raphy - the harbor from Lady Liberty’s perspective to Central Park as the birds experience it. against Satoru Kitaoka. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Cheers Prison Break Diane Meets Mom - Diane’s nervous about meeting Frasier’s mother Hester, who’s a Riots, Drills and the Devil - Michael’s ploy to buy some work time by prompting a cellblock renowned psychologist. Hester’s pleasant during dinner, but when Frasier leaves them alone, lockdown leads to a full-scale riot; Nick convinces Veronica that he really does want to help she threatens to kill Diane if she continues to interfere with her son’s life. her; and Kellerman hires an inmate to kill Lincoln. 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT Cheers JAG An American Family - Carla’s ex-husband returns with his new bride, demanding custody of Offensive Action - In a P-3 Squadron over the Pacific Ocean, Cmdr. O’Neil hounds Lt. Kersey their oldest son. The normally feisty Carla shocks everyone at the bar when she agrees to the during a mission. -

Eastern Progress

Colonels tackle the Toppers in a 30-10 i ^ ^p* Thei ne Easterneastern victory over the weekend in the uni- versity's oldest .H rivalry/BS fX Progress^^y www.progress.eku.edu week • Regents pass tuition increase, word change BY SHAWN How— "I am absolutely confident that already increased base will be increase. Pace said that this didn't mean There was no doubt about it News editor xthisiis what it will take to achieve raised another 7.5 percent That just seems wrong," Pace students supported it that I was going to be left out in th~e~"nHs.sion of this university," Student Regent Chris Pace, said. This university is supposed "Just because there's apathy, the rain," Pace said of the vote. The Board of Regents voted Kustra said. "The focus here is on who cast the sole vote against the Saturday on a tuition raise and to be inclusive. When we start rais- this is not a vote of approval," He was critical of the board for academic quality. This is what it's new rate, asked why 7.5 percent ing tuition at that kind of rate all Pace said. not considering his points. adding sexual orientation to the going to take to get there." was necessary. discrimination clause. we're doing is excluding people." Pace said that it didn't matter "Maybe that in part contributes Kustra admitted the proposed "I think that's too high," Pace Kustra said that the state had what tuition rates had been in the to the apathy that you see, that This is die first time Eastern can increases would be on the "high said. -

Acoustic Guitar

45 ACOUSTIC GUITAR THE CHRISTMAS ACOUSTIC GUITAR METHOD FROM ACOUSTIC GUITAR MAGAZINE COMPLETE SONGS FOR ACOUSTIC BEGINNING THE GUITAR GUITAR ACOUSTIC METHOD GUITAR LEARN TO PLAY 15 COMPLETE HOLIDAY CLASSICS METHOD, TO PLAY USING THE TECHNIQUES & SONGS OF by Peter Penhallow BOOK 1 AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC Acoustic Guitar Private by David Hamburger by David Hamburger Lessons String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing Please see the Hal Leonard We’re proud to present the Books 1, 2 and 3 in one convenient collection. Christmas Catalog for a complete description. first in a series of beginning ______00695667 Book/3-CD Pack..............$24.95 ______00699495 Book/CD Pack...................$9.95 method books that uses traditional American music to teach authentic THE ACOUSTIC EARLY JAZZ techniques and songs. From the folk, blues and old- GUITAR METHOD & SWING time music of yesterday have come the rock, country CHORD BOOK SONGS FOR and jazz of today. Now you can begin understanding, GUITAR playing and enjoying these essential traditions and LEARN TO PLAY CHORDS styles on the instrument that truly represents COMMON IN AMERICAN String Letter Publishing American music: the acoustic guitar. When you’re ROOTS MUSIC STYLES Add to your repertoire with done with this method series, you’ll know dozens of by David Hamburger this collection of early jazz the tunes that form the backbone of American music Acoustic Guitar Magazine and swing standards! The and be able to play them using a variety of flatpicking Private Lessons companion CD features a -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Hdnet Canada Schedule for Mon. April 16, 2012 to Sun. April 22, 2012 Monday April 16, 2012

HDNet Canada Schedule for Mon. April 16, 2012 to Sun. April 22, 2012 Monday April 16, 2012 1:00 PM ET / 10:00 AM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Nothing But Trailers IMAX - The Alps Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So HDNet presents a half hour of Noth- In the air above Switzerland, on the sheer rock-and-ice wall known as the Eiger, an American ing But Trailers. See the best trailers, old and new in HDNet’s collection. climber is about to embark on the most perilous and meaningful ascent he has ever under- taken: an attempt to scale the legendary mountain that took his renowned father’s life. The 1:30 PM ET / 10:30 AM PT film celebrates the unsurpassed beauty of the Alps and the indomitable spirit of the people HDNet Music Discovery who live there. HDNet Music Discovery gives up-and-coming bands a chance to broadcast HD music videos in crystal clear true high definition and 5.1 Surround Sound on HDNet. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT Cheers 1:55 PM ET / 10:55 AM PT From Beer To Eternity - The Cheers gang challenges the regulars from a rival bar to a bowling Chris Isaak - Greatest Hits tournament to avenge their losses in a variety of other sporting events. When another defeat Isaak graces the stage with a compelling set that spans his early years on through the new seems on the way, they produce an unexpected ace. millennium. The performance launches with “Dancin” from his debut. -

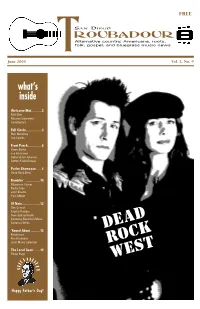

Feb. Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, Tfolk, gospel, and bluegrass music news June 2003 Vol. 2, No. 9 what’s inside Welcome Mat………3 Mail Box Mission Statement Contributors Full Circle..…………4 Bart Mendoza Lou Curtiss Front Porch…………6 Owen Burke Los Alacranes Deborah Liv Johnson Cotton Patch Gospel Parlor Showcase...…8 Dead Rock West Ramblin’ …………10 Bluegrass Corner Radio Daze José Sinatra Paul Abbott Of Note.……………12 Dan Connor Crystal Yoakum Sven-Erik Seaholm Kentucky Mountain Music Clarence White AD ‘Round About .......…13 DE Ranthouse The Firehouse K June Music Calendar ROC The Local Seen……15 Photo Page T WES Happy Father’s Day! Phil Harmonic Sez: new quote to come You grow up the day you have the first real laugh . at yourself. — Ethel Barrymore San Diego Troubadour • June 2003 welcomewelcome matmat SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, MAILBOX Tfolk, gospel, and bluegrass music news Dear Troubadour, going to play guitar I needed to MISSION CONTRIBUTORS Thank you for the article on be able to sing. When I showed To promote, encourage, and Indian Joe Stewart. It was great some interest in writing my own provide an alternative voice for PUBLISHER to see him get a little credit for songs, he helped me take my the great local music that is Lyle Duplessie all he has done in and for the jumbled high school thoughts generally overlooked by the mass media; namely the genres EDITOR local music scene. When I was in and turn them into something of folk, country, roots, Ellen Duplessie high school, I took guitar worth listening to. -

311 and the Offspring Announce Co-Headline ‘Never-Ending Summer Tour’ with Special Guests Gym Class Heroes

311 AND THE OFFSPRING ANNOUNCE CO-HEADLINE ‘NEVER-ENDING SUMMER TOUR’ WITH SPECIAL GUESTS GYM CLASS HEROES Tickets On Sale to General Public Starting Friday, April 13 at LiveNation.com LOS ANGELES (April 9, 2018) – Two of rock’s most notable live bands, 311 and The Offspring, announced they are teaming up for the Never-Ending Summer Tour, a fun-filled summer amphitheater outing with special guests Gym Class Heroes. The tour will also make stops at select regional events throughout the summer. See below for itinerary. The feel good tour of the summer, produced by Live Nation, will kick off July 25 at Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, CA and hit 29 cities across North America before wrapping September 9 in Wichita, KS. Fans can expect an amazing night of music with countless hits from all three bands making for a can’t miss event this summer. Citi® is the official presale credit card for the 311 and The Offspring tour. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase U.S. presale tickets beginning Tuesday, April 10 at 12pm local time until Thursday, April 12 at 10pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Tickets will go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, April 13 at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Never-Ending Summer Tour Dates: Wednesday, July 25 Mountain View, CA Shoreline Amphitheatre Friday, July 27 Salt Lake City, UT USANA Amphitheatre Saturday, July 28 Las Vegas, NV* Downtown Las Vegas Events Center Sunday, July 29 Chula Vista, CA Mattress -

Song Name Artist

Sheet1 Song Name Artist Somethin' Hot The Afghan Whigs Crazy The Afghan Whigs Uptown Again The Afghan Whigs Sweet Son Of A Bitch The Afghan Whigs 66 The Afghan Whigs Cito Soleil The Afghan Whigs John The Baptist The Afghan Whigs The Slide Song The Afghan Whigs Neglekted The Afghan Whigs Omerta The Afghan Whigs The Vampire Lanois The Afghan Whigs Saor/Free/News from Nowhere Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 1 Afro Celt Sound System Inion/Daughter Afro Celt Sound System Sure-As-Not/Sure-As-Knot Afro Celt Sound System Nu Cead Againn Dul Abhaile/We Cannot Go... Afro Celt Sound System Dark Moon, High Tide Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 2 Afro Celt Sound System House Of The Ancestors Afro Celt Sound System Eistigh Liomsa Sealad/Listen To Me/Saor Reprise Afro Celt Sound System Amor Verdadero Afro-Cuban All Stars Alto Songo Afro-Cuban All Stars Habana del Este Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba le Gusta Afro-Cuban All Stars Fiesta de la Rumba Afro-Cuban All Stars Los Sitio' Asere Afro-Cuban All Stars Pío Mentiroso Afro-Cuban All Stars Maria Caracoles Afro-Cuban All Stars Clasiqueando con Rubén Afro-Cuban All Stars Elube Chango Afro-Cuban All Stars Two of Us Aimee Mann & Michael Penn Tired of Being Alone Al Green Call Me (Come Back Home) Al Green I'm Still in Love With You Al Green Here I Am (Come and Take Me) Al Green Love and Happiness Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green I Can't Get Next to You Al Green You Ought to Be With Me Al Green Look What You Done for Me Al Green Let's Get Married Al Green Livin' for You [*] Al Green Sha-La-La -

Feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77

01. 50 Cent - Intro (0:06) 75. Ace Of Base - Life Is A Flower (3:44) 02. 50 Cent - What Up Gangsta? (2:59) 76. Ace Of Base - C'est La Vie (3:27) 03. 50 Cent - Patiently Waiting (feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77. Ace Of Base - Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Mix) 04. 50 Cent - Many Men (Wish Death) (4:16) (3:42) 05. 50 Cent - In Da Club (3:13) 78. Ace Of Base - Beautiful Life (Junior Vasquez Mix) 06. 50 Cent - High All the Time (4:29) (8:24) 07. 50 Cent - Heat (4:14) 79. Acoustic Guitars - 5 Eiffel (5:12) 08. 50 Cent - If I Can't (3:16) 80. Acoustic Guitars - Stafet (4:22) 09. 50 Cent - Blood Hound (feat. Young Buc) (4:00) 81. Acoustic Guitars - Palosanto (5:16) 10. 50 Cent - Back Down (4:03) 82. Acoustic Guitars - Straits Of Gibraltar (5:11) 11. 50 Cent - P.I.M.P. (4:09) 83. Acoustic Guitars - Guinga (3:21) 12. 50 Cent - Like My Style (feat. Tony Yayo (3:13) 84. Acoustic Guitars - Arabesque (4:42) 13. 50 Cent - Poor Lil' Rich (3:19) 85. Acoustic Guitars - Radiator (2:37) 14. 50 Cent - 21 Questions (feat. Nate Dogg) (3:44) 86. Acoustic Guitars - Through The Mist (5:02) 15. 50 Cent - Don't Push Me (feat. Eminem) (4:08) 87. Acoustic Guitars - Lines Of Cause (5:57) 16. 50 Cent - Gotta Get (4:00) 88. Acoustic Guitars - Time Flourish (6:02) 17. 50 Cent - Wanksta (Bonus) (3:39) 89. Aerosmith - Walk on Water (4:55) 18. -

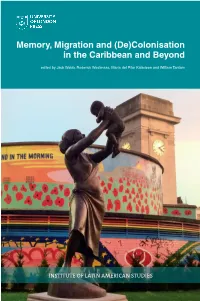

Colonisation in the Caribbean and Beyond

Memory, Migration and (De)Colonisation in the Caribbean and Beyond edited by Jack Webb, Roderick Westmaas, Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and William Tantam INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Memory, Migration and (De)Colonisation in the Caribbean and Beyond edited by Jack Webb, Rod Westmaas, Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and William Tantam University of London Press Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2020 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/. This book is also available online at http://humanities-digital-library.org. ISBN: 978-1-908857-65-1 (paperback edition) 978-1-908857-66-8 (.epub edition) 978-1-908857-67-5 (.mobi edition) 978-1-908857-76-7 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/220.9781908857767 (PDF edition) Institute of Latin American Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House London WC1E 7HU Telephone: 020 7862 8844 Email: [email protected] Web: http://ilas.sas.ac.uk Cover image: The Bronze Woman, Stockwell. Photograph by Cecile Nobrega. This book is dedicated to the Bronze Woman Charity, who with the OLMEC Charity work tirelessly for the Children of the Windrush. The Bronze Woman Statue, located in Stockwell Gardens, and depicted on the cover of this book, was the brainchild of Cecile Nobrega, a poetess, who was relentless in her pursuit to honour Caribbean womanhood. -

Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960S Psychedelic Esthetic and “San Francisco Sound"

University of Nevada, Reno Rockin’ the Comstock: Exploring the Unlikely and Underappreciated Role of a Mid-Nineteenth Century Northern Nevada Ghost Town (Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960s Psychedelic Esthetic and “San Francisco Sound" A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Engrid Barnett Dr. Paul F. Starrs/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 © Copyright by Engrid Barnett, 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Engrid Barnett entitled Rockin’ the Comstock: Exploring the Unlikely and Underappreciated Role of a Mid-Nineteenth Century Northern Nevada Ghost Town (Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960s Psychedelic Esthetic and "San Francisco Sound" be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Paul Starrs, PhD, Advisor and Committee Chair Donald Hardesty, PhD, Committee Member Alicia Barber, PhD, Committee Member Jill S. Heaton, PhD, Committee Member David Ake, PhD, Graduate School Representative Marsha H Read, PhD, Dean of the Graduate School May 2014 i ABSTRACT Virginia City, Nevada, epitomized and continues to epitomize a liminal community — existing on the very limen of the civilized and uncivilized, legitimate and illegitimate, parochial frontier and cosmopolitan metropolis. Throughout a 150-year history, its thea- ters attracted performers of national and international acclaim who entertained a diverse civic population