Of Business and Pleasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Anne-Sophie Adelys

by Anne-Sophie Adelys © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 3 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz My name is Anne-Sophie Adelys. I’m French and have been living in New Zealand since 2001. I’m an artist. A painter. Each week I check “The Big idea” website for any open call for artists. On Saturday the 29th of June 2013, I answered an artist call titled: “Artist for a fringe campaign on Porn” posted by the organisation: The Porn Project. This diary documents the process of my work around this project. I’m not a writer and English is not even my first language. Far from a paper, this diary only serves one purpose: documenting my process while working on ‘The Porn Project’. Note: I have asked my friend Becky to proof-read the diary to make sure my ‘FrenchGlish’ is not too distracting for English readers. But her response was “your FrenchGlish is damn cute”. So I assume she has left it as is… © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 4 4 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz The artist call as per The Big Idea post (http://www.thebigidea.co.nz) Artists for a fringe campaign on porn 28 June 2013 Organisation/person name: The Porn Project Work type: Casual Work classification: OTHER Job description: The Porn Project A Fringe Art Campaign Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, Aotearoa/New Zealand August, 2013 In 2012, Pornography in the Public Eye was launched by people at the University of Auckland to explore issues in relation to pornography through research, art and community-based action. -

Snuff Boxing: Revisiting the Snuff Coda | Cinephile: the University of British Columbia�S Film Journal

13/03/2012 Snuff Boxing: Revisiting the Snuff Coda | Cinephile: The University of British Columbia’s Film Journal You are here: Home » Archives » Volume 5 No. 2: The Scene » Snuff Boxing: Revisiting the Snuff Coda SNUFF BOXING: REVISITING THE SNUFF CODA Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Snuff (Findlay/Nuchtern, 1976) might not be the ‘best’ film produced in the Americas in the 1970s, but it may be the decade’s most important ‘worst’ film. Rumoured to depict the actual murder of a female crewmember in its final moments, its notoriety consolidated the urban legend of snuff film. The snuff film legacy has manifested across a broad range of media, from fictional snuff narratives like Vacancy (Nimród Antal, 2007) and 8mm (Joel Schumacher, 1999), to purportedly real snuff footage distributed online and through mobile phones. Despite Snuff’s status as a unique trash artefact, the suddenness with which the controversy exploded into the public arena allowed it very little time for a ‘micro’ analytical moment.[1] The snuff film enigma was so intoxicatingly extra-diegetic that it instantly transcended the nuts-and-bolts details of the film itself. The shocking impact of those final five minutes appeared to render close analysis unnecessary: Snuff, like snuff, was predicated upon a hyperactive theatricality of ambiguity, rumour and moral panic. cinephile.ca/archives/volume-5-no-2-the-scene/snuff-boxing-revisiting-the-snuff-coda/ 1/9 13/03/2012 Snuff Boxing: Revisiting the Snuff Coda | Cinephile: The University of British Columbia’s Film Journal The power inherent in the word “snuff” is dependent upon its vagueness; its enigmatic force stems directly from its nebulousness as a concept. -

Pre-Print Version.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Sayad, Cecilia (2016) Found-Footage Horror and the Frame's Undoing. Cinema Journal . ISSN 0009-7101. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/42009/ Document Version Author's Accepted Manuscript Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Found-Footage Horror and the 1 Frame’s Undoing 2 3 by CECILIA SAYAD 4 5 Abstract: This article fi nds in the found-footage horror cycle an alternative way of under- 6 standing the relationship between horror fi lms and reality, which is usually discussed 7 in terms of allegory. I propose the investigation of framing, considered both fi guratively 8 (framing the fi lm as documentary) and stylistically (the framing in handheld cameras 9 and in static long takes), as a device that playfully destabilizes the separation between 10 the fi lm and the surrounding world. -

Post-Human Nightmares

Post-Human Nightmares Mark Player 13 May 2011 A man wakes up one morning to find himself slowly transforming into a living hybrid of meat and scrap metal; he dreams of being sodomised by a woman with a snakelike, strap-on phallus. Clandestine experiments of sensory depravation and mental torture unleash psychic powers in test subjects, prompting them to explode into showers of black pus or tear the flesh off each other's bodies in a sexual frenzy. Meanwhile, a hysterical cyborg sex-slave runs amok through busy streets whilst electrically charged demi-gods battle for supremacy on the rooftops above. This is cyberpunk, Japanese style : a brief filmmaking movement that erupted from the Japanese underground to garner international attention in the late 1980s. The world of live-action Japanese cyberpunk is a twisted and strange one indeed; a far cry from the established notions of computer hackers, ubiquitous technologies and domineering conglomerates as found in the pages of William Gibson's Neuromancer (1984) - a pivotal cyberpunk text during the sub-genre's formation and recognition in the early eighties. From a cinematic standpoint, it perhaps owes more to the industrial gothic of David Lynch's Eraserhead (1976) and the psycho-sexual body horror of early David Cronenberg than the rain- soaked metropolis of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982), although Scott's neon infused tech-noir has been a major aesthetic touchstone for cyberpunk manga and anime institutions such as Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira (1982- 90) and Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell (1989- ). In the Western world, cyberpunk was born out of the new wave science fiction literature of the sixties and seventies; authors such Harlan Ellison, J.G. -

Proto-Cinematic Narrative in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2016 Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction Kara Marie Manning University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Manning, Kara Marie, "Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction" (2016). Dissertations. 906. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/906 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVING WORDS/MOTION PICTURES: PROTO-CINEMATIC NARRATIVE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION by Kara Marie Manning A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Eric L.Tribunella, Committee Chair Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Monika Gehlawat, Committee Member Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Phillip Gentile, Committee Member Assistant Professor, -

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985 By Xavier Mendik Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985, By Xavier Mendik This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Xavier Mendik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5954-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5954-7 This book is dedicated with much love to Caroline and Zena CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Enzo G. Castellari Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Bodies of Desire and Bodies of Distress beyond the ‘Argento Effect’ Chapter One .............................................................................................. 21 “There is Something Wrong with that Scene”: The Return of the Repressed in 1970s Giallo Cinema Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

'Emanuelle' Films

Issue 9 May 2017 www.intensitiescultmedia.com Mondo Realism, the Sensual Body, and Genre Hybridity in Joe D’Amato’s ‘Emanuelle’ Films Mario DeGiglio-Bellemare John Abbott College Abstract This paper examines the place of Joe D’Amato’s series of Emanuelle films within the context of Italian cine- ma, exploitation cinema, and genre studies—especially the pornography and horror genres. I will focus on what I have labelled D’Amato’s Mondo Realist films that were made in a very short period between 1975-1978. I argue that D’Amato’s films offer an expansive sense of genre hybridity, especially as his films from this brief period are rooted in the Sadean tradition, the cinema of attractions, the Mondo film, neorealism, and the horror genre. I also examine D’Amato’s films in the terms set out by Linda Williams (2004a); namely, as an auteur of ‘body genres’ whose films must be considered in terms that move us beyond dominant scopocentric tendencies in film theory. D’Amato’s films offer a way to open up these categories through the sensual and corporeal experience of his hybrid films. Introduction The opening credit sequence is constructed through is not new to the landscape of Italian cinema: it is the a series of shots that showcase the sights of New main theme of Mondo Cane (Dirs. Paolo Cavara, Gual- York City from the air. The film opens with the name tiero Jacopetti, Franco E. Prosperi, 1962), the film that of Laura Gemser superimposed on the imposing set in motion another important Italian subgenre skyline of the Twin Towers. -

The Snuff Film the Making of an Urban Legend

URBAN LEGENDS Introduction BY JAN HAROLD BRUNVAND PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF ENGLISH, UNIVERSITY OF UTAH Urban legends—as I wrote in American Folklore: An Encyclopedia Many urban legends, as the writers of the following two essays recog- (Garland. 1996)—are apocryphal contemporary stories, told as true but nize, are benign, silly barely credible, and easily disproved: they are told incorporating traditional motifs, and usually attributed to a friend of a more for entertainment than for any moralistic purpose, although there is friend. The term, adopted by folklorists in the 1970s, has become familiar often an implicit message or warning in them as well. But other modern to members of the public and journalists (who sometimes use the less accu- legends are potentially dangerous, leading people to make decisions unwar- rate term "urban myth") to refer to many of the odd, unverified and "true" ranted by any facts. (I think particularly of legends about crime, many of rumors and stories that circulate both orally and in the media. Despite this which take the form of "bogus warnings. ") The two essays published here public awareness and the best efforts of scholars and investigative reporters confront urban legends of this kind, showing how the baseless stories about to debunk them, such stories—both new and old—continue to be spread organ-thefts and snuff films grew, spread and to some degree affected pub- avidly especially on the Internet. Thus, my own version of the last sentence lic policy It's notable that neither of these writers is a professional folklorist; of Scott Stine's article that follows (which I use as a motto on my e-mail apparently, the lessons of folklore research in this fascinating area of mod- signature block), is "The truth never stands in the way of a good story " ern tradition are spreading, just like the legends themselves. -

Found-Footage Horror and the Frame's Undoing

Found-Footage Horror and the Frame’s Undoing by CECILIA SAYAD Abstract: This article fi nds in the found-footage horror cycle an alternative way of under- standing the relationship between horror fi lms and reality, which is usually discussed in terms of allegory. I propose the investigation of framing, considered both fi guratively (framing the fi lm as documentary) and stylistically (the framing in handheld cameras and in static long takes), as a device that playfully destabilizes the separation between the fi lm and the surrounding world. The article’s main case study is the Paranormal Activity franchise, but examples are drawn from a variety of fi lms. urprised by her boyfriend’s excitement about the strange phenomena registered with his HDV camera, Katie (Katie Featherston), the protagonist of Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007), asks, “Are you not scared?” “It’s a little bizarre,” he replies. “But we’re having it documented, it’s going to be fi ne, OK?” S This reassuring statement implies that the fi lm image may normalize the events that make up the fabric of Paranormal Activity. It is as if by recording the slamming doors, fl oating sheets, and passing shadows that take place while they sleep, Micah and Katie could tame the demon that follows the female lead wherever she goes. Indeed, the fi lm repeatedly shows us the two characters trying to make sense of the images they capture, watching them on a computer screen and using technology that translates the recorded sounds they cannot hear into waves they can visualize. -

Freedman CV Full Copy

ERIC FREEDMAN School of Media Arts Columbia College Chicago EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES Doctor of Philosophy, December 1998 Critical Studies, School of Cinematic Arts UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES Master of Arts (Non-Terminal), May 1991 Art History, School of Fine Arts CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NEW YORK Bachelor of Arts, Magna Cum Laude with Honors, May 1987 Art History, School of Arts and Sciences AREAS OF RESEARCH New Media, Public Policy and New Technologies, Video Game Studies, Television Studies, Film Studies, Documentary and Experimental Video, Community Media, Autobiography ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO Dean, School of Media Arts, July 2016-present - Lead the School in the continued implementation of the College’s strategic plan while overseeing a $24 million budget. Provide direction for four academic departments, working with chairs, faculty and staff to realize new unit models: Audio Arts and Acoustics, Cinema and Television Arts, Communication, and Interactive Arts and Media. Focused attention to academic curriculum, planning, budgeting, goal setting, and interdepartmental collaboration. Responsible for proper alignment of enrollment and resources to programs. The School of Media Arts has an enrollment of 2985 students, with 90 staff, 82 full-time faculty and 270 part-time faculty. - Participate as a member of the Academic Affairs senior leadership team, and serve as a change leader to build and support College-wide approaches, structures and systems around student recruitment and retention; student success; alumni relations; community engagement; branding and communication; transfer student initiatives; online, professional and graduate education; global education; accreditation, assessment and program review; and budget management. - Develop new revenue streams through curricular transformation, student recruitment and retention, and new program development. -

Incorporating Emotions Specific to the Sexual Response Into Theories Of

Arch Sex Behav DOI 10.1007/s10508-010-9669-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Incorporating Emotions Specific to the Sexual Response into Theories of Emotion Using the Indiana Sexual and Affective Word Set Ryan A. Stevenson • Laurel D. Stevenson • Heather A. Rupp • Sunah Kim • Erick Janssen • Thomas W. James Received: 17 February 2009 / Revised: 27 January 2010 / Accepted: 26 June 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract The sexual response includes an emotional com- analysis, we found that one word category or factor, labeled ponent, but it is not clear whether this component is specific to ‘‘sexual,’’was predicted only by the new sexual arousal and sex and whether it is best explained by dimensional or discrete energy scales. The remaining three factors, labeled‘‘disgust- emotion theories. To determine whether the emotional com- ing,’’‘‘happy,’’ and ‘‘basic aversive’’ were best predicted by ponent of the sexual response is distinct from other emotions, basic (or discrete) emotion ratings. Dimensional ratings of participants (n = 1099) rated 1450 sexual and non-sexual words valence, sexual valence, and arousal were not predictive of according to dimensional theories of emotion (using scales of any of the four categories. These results suggest that the addition valence, arousal, and dominance) and according to theories of of sexually specific emotions to basic emotion theories is jus- basic emotion (using scales of happiness, anger, sadness, fear, tified and needed to account fully for emotional responses to and disgust). In addition, ratings were provided for newly devel- sexual stimuli. In addition, the findings provide initial validation oped scales of sexual valence, arousal, and energy. -

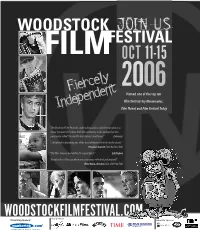

Wff Freeman Insert

JOIN US OCT 11-15 llyy 2006 FFiieerrccee nnddeenntt Named one of the top ten ddeeppee film festivals by Moviemaker, IInn Film Threat and Film Festival Today “The Woodstock Film Festival is quite a draw,and its solid line-up attracts a broad spectrum of the New York film community to the enclave that one participant called “the world’s most famous small town.” (Indiewire) “...Woodstock is becoming one of the most distinctive festivals on the circuit.” (Stephen Garrett,Time Out New York) “The films here are wonderful,it’s a great place.” (Lili Taylor) “Woodstock is a film spa where you come away refreshed and inspired!” (Ron Mann, director, Tales of the Rat Fink) ©R WOODSTOCKFILMFESTIVAL.COM oth 2006 Key Sponsors: Presenting Sponsor: Superstar Sponsor: ABOUT WOODSTOCK FILM FESTIVAL The Woodstock Film Festival As a not-for-profit, 501(c)(3) organization, our mission is to present an annual program and celebrates new and established year-round schedule of film, music and art-related activities that promote artists, culture and inspires learning and diversity. The Hudson Valley Film Commission promotes sustainable voices in independent film with economic development by attracting and supporting film, video and media production. screenings, seminars, workshops Every fall, film and music lovers from around the world gather here for an exhilarating variety of films, concerts, celebrity-led seminars, workshops, an awards ceremony and and concerts throughout the mid- superlative parties. Visitors find themselves in a relaxed, receptive atmosphere surrounded by Hudson Valley. some of the most beautiful landscapes in the world. More than 125 films are screening, including feature films, documentaries and shorts, many of which are premieres from the U.S.