The Implications of Space and Mobility in James Cameronâ•Žs Titanic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

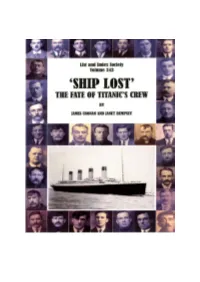

Titanic Crew

Titanic continues to capture the popular imagination even 100 hundred years after her tragic loss in the North Atlantic in 1912. However much of that focus is on the disparity between the survival rates of the first and third class passengers and the loss of the rich and famous on board. Often overlooked are the crew of the Titanic of whom four out of five lost their lives in the disaster. James Cronan and Janet Dempsey have used the original Titanic crew records held at the National Archives to attempt to redress this balance, not only looking at the crew who lost their lives but also following the fate of those who survived and in many cases actually carried on a career at sea. This definitive reference work includes a listing of all Titanic’s crew, recording those who were lost and saved; a gallery of unique previously unseen photographs of Titanic crew survivors; five in depth case studies including Captain E.J.Smith, Violet Jessop and Frederick Woodford; an in depth analysis of the crew list and guidance on how to undertake research with regards to Merchant Navy officers and seamen in the early twentieth century. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To the Treasurer, List and Index Society (LIS 12), c/o The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, TW9 4DU, UK Please supply …. ..copies of Ship Lost – The Fate of Titanic’s Crew on publication at £22 which includes UK p&p and List and Index membership which entitles members to discounts on previous and future List and Index Society publications. Please supply ….. copies of Ship Lost – The Fate of Titanic’s Crew on publication at the non-members rate of £21 plus £3 UK p&p. -

Captain Arthur Rostron

CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CARPATHIA Created by: Jonathon Wild Campaign Director – Maelstrom www.maelstromdesign.co.uk CONTENTS 1 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………3-6 CUNARD LINE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7-8 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…….….……………………………………………………………………………………………………….8-9 RMS CARPATHIA…………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………….9-10 SINKING OF THE RMS TITANIC………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…11-17 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18-23 R.M.S CARPATHIA – Copyright shipwreckworld.com 2 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON Sir Arthur Henry Rostron, KBE, RD, RND, was a seafaring officer working for the Cunard Line. Up until 1912, he was an unknown person apart from in nautical circles and was a British sailor that had served in the British Merchant Navy and the Royal Naval Reserve for many years. However, his name is now part of the grand legacy of the Titanic story. The Titanic needs no introduction, it is possibly the most known single word used that can bring up memories of the sinking of the ship for the relatives, it will reveal a story that is still known and discussed to this day. And yet, Captain Rostron had no connections with the ship, or the White Star Line before 1912. On the night of 14th/15th April 1912, because of his selfless actions, he would be best remembered as the Captain of the RMS Carpathia who rescued many hundreds of people from the sinking of the RMS Titanic, after it collided with an iceberg in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. Image Copyright 9gag.com Rostron was born in Bolton on the 14th May 1869 in the town of Bolton. His birthplace was at Bank Cottage, Sharples to parents James and Nancy Rostron. -

THE “TITANIC” MOVIE by JAMES CAMERON Your Name Course

THE “TITANIC” MOVIE BY JAMES CAMERON Your Name Course #, Movie Review mm dd, yyyy The “Titanic” Movie by James Cameron The publicity around the 1997 “Titanic” movie was on my mind, when I went to see it. I was keen to see the ship, in particular, and to see how they depicted the accident. I had read the book “A Night to Remember", so I had an idea of the events of the night, but wanted to see the spectacle which the movie's director, James Cameron had created. The movie exceeded my expectations. The action, story, the special effects, the social reality of the class distinction, and the music all combined to make it an enjoyable movie. As the primary reason for Titanic’s fame was its tragic sinking, this was a pleasant surprise. It was not a depressing movie. The story line must take the credit. Leonardo Di Caprio plays the role of Jack Dawson in “Titanic”, who is a young Irish boy. He wins passage to America aboard the Titanic. He did so in a poker game, and obtained the free ticket on the world’s newest liner. There, he met Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) who has been travelling to America to get married. She was very unhappy about the coming event, and planed to jump overboard. Dawson talked her out of it, and the on-board romance inevitably started and blossomed. It is this romance that gives the movie its feel of brilliantly good quality. Rose survives and goes on to choose her own destiny, after the ship sinks and Dawson drowns. -

Hunting Deer in California

HUNTING DEER IN CALIFORNIA We hope this guide will help deer hunters by encouraging a greater understanding of the various subspecies of mule deer found in California and explaining effective hunting techniques for various situations and conditions encountered throughout the state during general and special deer seasons. Second Edition August 2002 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Arnold Schwarzenegger, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME L. Ryan Broddrick, Director WILDLIFE PROGRAMS BRANCH David S. Zezulak, Ph.D., Chief Written by John Higley Technical Advisors: Don Koch; Eric Loft, Ph.D.; Terry M. Mansfield; Kenneth Mayer; Sonke Mastrup; Russell C. Mohr; David O. Smith; Thomas B. Stone Graphic Design and Layout: Lorna Bernard and Dana Lis Cover Photo: Steve Guill Funded by the Deer Herd Management Plan Implementation Program TABLE OF CON T EN T S INTRODUCT I ON ................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: THE DEER OF CAL I FORN I A .........................................................................................................7 Columbian black-tailed deer ....................................................................................................................8 California mule deer ................................................................................................................................8 Rocky Mountain mule deer .....................................................................................................................9 -

TITANIC and OLYMPIC

Marine Technology Special Collection, Newcastle University, United Kingdom. Titanic & Olympic TITANIC and OLYMPIC some documentary highlights held in the Marine Technology Special Collection, Newcastle University. Our Collection has some original company documents, some of which are unique, in addition to publications which describe the building, launching, operation, and scrapping of these two famous passenger liners. Our Collection is open to visitors by appointment where these materials can be consulted. Over a century after White Star’s flagship TITANIC was lost in 1912, she and her sister OLYMPIC continue to exert a fascination. The Collection has a number of items related to these ships, including information on OLYMPIC’s demolition in 1935:- 1. OLYMPIC furniture and fittings of Akzo Nobel (formerly Smith and Walton) paint makers of Haltwhistle 2004. 2. OLYMPIC construction and launching in two leading engineering magazines ‘The Engineer’ and ‘Engineering’ 1910-1911. 3. OLYMPIC and TITANIC construction published in ‘The Shipbuilder’ magazine midsummer 1911. 4. OLYMPIC ‘Bill of Sale’ from Cunard White Star to Ward shipbreakers dated 9 September 1935. 5. OLYMPIC photographs of arrival in the River Tyne on 13 October 1935 and subsequent demolition in Jarrow and Inverkeithing. 6. OLYMPIC auction catalogue of her fixtures and fittings during 5-18 Nov 1935 in Jarrow by Knight, Frank, & Rutley auctioneers by direction of Thos. W. Ward Ltd. 7. OLYMPIC outturn records of all the materials removed and recycled 1935-1937 in Jarrow by Thos. W. Ward Ltd. 8. ASTURIAS records of the use of this liner in 1957 in making the British drama film of 1958 “A Night to Remember” about the sinking of the TITANIC. -

Coordination Failure and the Sinking of Titanic

The Sinking of the Unsinkable Titanic: Mental Inertia and Coordination Failures Fu-Lai Tony Yu Department of Economics and Finance Hong Kong Shue Yan University Abstract This study investigates the sinking of the Titanic from the theory of human agency derived from Austrian economics, interpretation sociology and organizational theories. Unlike most arguments in organizational and management sciences, this study offers a subjectivist perspective of mental inertia to understand the Titanic disaster. Specifically, this study will argue that the fall of the Titanic was mainly due to a series of coordination and judgment failures that occurred simultaneously. Such systematic failures were manifested in the misinterpretations of the incoming events, as a result of mental inertia, by all parties concerned in the fatal accident, including lookouts, telegram officers, the Captain, lifeboat crewmen, architects, engineers, senior management people and owners of the ship. This study concludes that no matter how successful the past is, we should not take experience for granted entirely. Given the uncertain future, high alertness to potential dangers and crises will allow us to avoid iceberg mines in the sea and arrived onshore safely. Keywords: The R.M.S. Titanic; Maritime disaster; Coordination failure; Mental inertia; Judgmental error; Austrian and organizational economics 1. The Titanic Disaster So this is the ship they say is unsinkable. It is unsinkable. God himself could not sink this ship. From Butler (1998: 39) [The] Titanic… will stand as a monument and warning to human presumption. The Bishop of Winchester, Southampton, 1912 Although the sinking of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic (thereafter as the Titanic) is not the largest loss of life in maritime history1, it is the most famous one2. -

Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge Trails

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service This blue goose, designed Rocky Flats by J.N. “Ding” Darling, is the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. National Wildlife Refuge Trails Welcome Exploring the Refuge Accessibility Information Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge We invite you to enjoy the sights and Equal opportunity to participate in and offers expansive views of the Front Range sounds of the Refuge. To help protect benefit from programs and activities of the Rocky Mountains and rolling prairie wildlife and habitats, please keep the of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is grasslands, woodlands, and wetlands. This following rules in mind: available to all individuals regardless of 5,237-acre Refuge has been managed by ■ Visitor access is limited to designated physical or mental ability. Dial 711 for a the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since trails and roads as shown on the map. All free connection to and from people with 2007 to restore and preserve the native other areas are closed to visitor access. hearing and speech disabilities. For more prairie ecosystems, provide habitat for information or to address accessibility ■ Observe all posted signs and regulations. migratory and resident wildlife, conserve needs, please contact Rocky Mountain and protect habitat for Preble’s meadow ■ Park only in the designated areas Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge staff at jumping mouse, and provide research and shown on the map. 303 / 289 0930 or the U.S. Department of education opportunities. ■ Assistance dogs are welcome and must the Interior, Office of Equal Opportunity, be under leash control at all times. -

App. 1 UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the SECOND

App. 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO A SUMMARY ORDER FILED ON OR AFTER JAN- UARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOV- ERNED BY FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1 AND THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1.1. WHEN CITING A SUMMARY OR- DER IN A DOCUMENT FILED WITH THIS COURT, A PARTY MUST CITE EITHER THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR AN ELECTRONIC DA- TABASE (WITH THE NOTATION “SUMMARY ORDER”). A PARTY CITING TO A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF IT ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL. At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, 40 Foley Square, in the City of New York, on the 14th day of November, two thousand eighteen. PRESENT: ROBERT A. KATZMANN, Chief Judge, AMALYA L. KEARSE, DENNY CHIN, Circuit Judges. App. 2 EDWARD KRAMER, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. ANTONIO VITTI, No. 17-2467-cv STEPHEN STAUROVSKY, Defendants-Appellees, PETER FEARON, Defendant. For Plaintiff-Appellant: WILLIAM S. PALMIERI, Law Offices of William S. Palmieri, LLC, New Haven, CT. For Defendants-Appellees: JAMES N. TALLBERG (Patrick D. Allen, on the brief ), Karsten & Tallberg, LLC, Rocky Hill, CT. Appeal from a judgment of the United States Dis- trict Court for the District of Connecticut (Underhill, J.). UPON DUE CONSIDERATION, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DE- CREED that the judgment of the district court is AF- FIRMED. Plaintiff-appellant Edward Kramer appeals from a judgment of the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut (Underhill, J.) entered in favor of defendants-appellees Antonio Vitti and Stephen App. -

Saving the Survivors Transferring to Steam Passenger Ships When He Joined the White Star Line in 1880

www.BretwaldaBooks.com @Bretwaldabooks bretwaldabooks.blogspot.co.uk/ Bretwalda Books on Facebook First Published 2020 Text Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2020 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the prior written permission of the publisher: Bretwalda Books Unit 8, Fir Tree Close, Epsom, Surrey KT17 3LD [email protected] www.BretwaldaBooks.com ISBN 978-1-909698-63-5 Historian Rupert Matthews is an established public speaker, school visitor, history consultant and author of non-fiction books, magazine articles and newspaper columns. His work has been translated into 28 languages (including Sioux). Looking for a speaker who will engage your audience with an amusing, interesting and informative talk? Whatever the size or make up of your audience, Rupert is an ideal speaker to make your event as memorable as possible. Rupert’s talks are lively, informative and fun. They are carefully tailored to suit audiences of all backgrounds, ages and tastes. Rupert has spoken successfully to WI, Probus, Round Table, Rotary, U3A and social groups of all kinds as well as to lecture groups, library talks and educational establishments.All talks come in standard 20 minute, 40 minute and 60 minute versions, plus questions afterwards, but most can be made to suit any time slot you have available. 3 History Talks The History of Apples : King Arthur – Myth or Reality? : The History of Buttons : The Escape of Charles II - an oak tree, a smuggling boat and more close escapes than you would believe. -

Cultural Representations of Titanic in the 1950S

A Night to Remember: Cultural Representations of Titanic in the 1950s In the early morning hours of April 15, 1912, the thought to be “unsinkable” passenger steamship, the RMS Titanic, sank to the depths of the Atlantic Ocean after her collision with an iceberg a few hours prior. With her, she took 1,503 of her passengers and left 700 to witness this event that historians would call one of the great “social dramas” of the twentieth century. Over the last 100 years, Titanic has inspired a wealth of representations across various media forms and across different national and cultural contexts. These representations have used the Titanic, both consciously and subconsciously, to reflect on, articulate, and justify a wide range of ideological positions on issues such as gender, family, class, and national identity. Thus, Titanic’s ultimate historical significance does not lie with her wreckage at the bottom of the Atlantic, but instead with the reverberations of her sinking and the cultural reaction she inspired. Though Titanic’s career as an ocean liner was brief, her tenure as a cultural symbol endured. Many of the most known cultural representations of the Titanic have been films. Over the last century, a number of films have told and retold the story of Titanic, not in deference to the facts of the event but in the service of the needs of the people telling the story. An example of the most extreme case being the Nazi’s use of the ship as a subject for a 1943 propaganda film. But, the historical narrative of Titanic is also ripe for dramatic adaptation. -

How Did the Titanic Sink MA

Reading Comprehension DIFFICULTY : MEDIUM Within the hour, at around 12:30am on 15th April, the captain (Edward J Smith) orders the lifeboats to be lowered. Once lowered, in just 10 minutes, passengers begin their escape, with women and children (from first-class only) occupying the first available spaces in the lifeboats; consequently, passengers from the second and third-class areas begin to rebel. Distressingly, the lifeboat system is only designed to ferry passengers to nearby rescue vessels, not to hold Many people are unaware of the true events which led to the sinking of the Titanic over everyone on board at the same time; therefore with the water from the lower decks rising 100 years ago. At 11:40pm on Sunday 14th April 1912, the fateful ship is just four days in rapidly and the chance of help reaching them in time, there is no safe refuge for all passen- to its maiden voyage when it fatally strikes an iceberg. What led to these tragic events and gers and sadly some lifeboats are launched before being at full capacity. how did the ocean liner end up at the bottom of the Atlantic? Following that, with the rescue attempts still continuing in earnest, the real implications of the The RMS Titanic, which is the largest passenger liner in service of the time, departs South- collision begin to show as the ship’s lights go out – causing further widespread panic and worry. ampton, England on April 10, 1912 travelling to New York City, across the Atlantic Ocean. The vast amount of water mixed with electrics caused this, meaning the ship is now even When it sets sail, it has an estimated 2,224 people on board – a mixture of rich and poor harder to track down should anyone be able to respond to SOS signals. -

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment Announces New Programming for Crackle for August

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment Announces New Programming for Crackle for August August 2, 2021 Mix of Hollywood Blockbusters, Award-Winning Indies, Classic TV and Hand-Picked Exclusive and Original Content COS COB, Conn., Aug. 02, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment Inc. (Nasdaq: CSSE), one of the largest operators of streaming advertising-supported video-on-demand (AVOD) networks, today announced the upcoming content releases for Crackle for August. The three primary Crackle Plus networks, Crackle, Popcornflix, and Chicken Soup for the Soul, are rolling out to new distribution touch points on up to 41 platforms on an ongoing basis as either AVOD or FAST channels. The Crackle Plus networks are currently distributed through 49 touch points in the U.S. with plans to expand to 64 touch points including Amazon FireTV, RokuTV, Apple TV, Smart TVs (Samsung, LG, Vizio), gaming consoles (PS4 and XBoxOne), Plex, iOS and Android mobile devices and on desktops at Crackle.com. Crackle is also available in approximately 500,000 hotel rooms in the Marriott Bonvoy chain. New Crackle AVOD Exclusive Skyfire (August 1st), A young scientist (Hannah Quinlivan) invents a cutting-edge volcanic warning system and returns to the tropical island where her mother tragically died, hoping she can prevent future deaths. The island is now home to the world's only volcano theme park and resort, the brainchild of its reckless owner Jack (Jason Isaacs). Chaos soon erupts when the once dormant volcano starts to rumble. It’s a battle with nature to get off the island while fiery death and destruction rains down from the mountain.