Shoma Ajoy Chatterji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zubeidaa Movie Torrent

Zubeidaa Movie Torrent 1 / 4 2 / 4 Zubeidaa Movie Torrent 3 / 4 Watch[720p] Zubeidaa (2001) HD QualityWith HD Quality.. Check out this video on Streamable using your phone, tablet or desktop.. Zubeidaa, an aspiring Muslim actress, marries a Hindu prince to become his second wife. Her tumultuous ... Watch Zubeidaa (2001) YiFy HD Torrent · Romance .... Indian movie zubeidaa, indian movies, indian movies 2018, indian ... on netflix, indian movies with english subtitles, indian movies torrent, .... Born into a rather filmy family, I've grown up on a steady diet of Hindi movies. From mainstream masala ones to the serious, arthouse movies, .... Zubeidaa, an aspiring Muslim actress, marries a Sikh prince to become his second ... Trending Hindi Movies and Shows ... Karisma Kapoor in Zubeidaa (2001).. DOWNLOAD: http://urllie.com/nkm3c Zubeidaa 5 torrent download locations monova.org Zubeidaa Movies 1 day . Hawaii.Five-0.2010.. ... zubeidaa join movie-mahekimahekihai cacheddownload zubeidaa she reaps ... hindi Tomatoes community nov , urdu is a indian Dvdrip torrent from zubeidaa .... By opting to have your ticket verified for this movie, you are allowing us to check the email address associated with your Rotten Tomatoes .... 1080p 720p 480p BluRay Movies Latest Bollywood Hollwood Movies . Download Hindi Dubbed Movies Torrent.. Zubeidaa (Full Movie) 1-17.. The film begins with Riyaz (Rajat Kapoor), Zubeida's son setting out to research her life, and to meet the people who knew her. The story is thus told in the form .... Zubeidaa, an aspiring Muslim actress, marries a Hindu prince to become his second wife. Her tumultuous relationship with her husband, and her inner demons ... -

NYIFF Announces Its 2012 Line-Up of Award-Winning Films

20 April -26 April 2012 NATIONAL/ INTERNATIONAL 4 IndiGo withdraws and Jet Airways limits inventory from makemytrip.com MUMBAI: IndiGo on Mon- day withdrew and Jet Air- ways limited its inventory on major travel portal makemytrip.com. Jet Air- ways blamed 'commercial reasons' for the move, but IndiGo issued a statement sayingthe move was prompted by 'arbitrary dis- 'opaque pricing' is anti-con- its inventory from the portal only Jet Airways and IndiGo play of fares and opaque sumer and in violation of but 'limited the inventory had kept away from it. pricing'. Jet and IndiGo were DGCA norms and direc- available to them for Director general, not part of the 'opaque fare' tives. We have raised this sale'.Officials familiar with DGCA, E K Bharat Bhushan schemes the portal offered. issue on several occasions, the issue said many carri- said that no 'opaque fare' are The schemes were stopped but, unfortunately, there has ers felt that the portal was on offer now. "We had checked late in March after the Di- been no resolution. We favouring a cash-strapped it out four days ago and rectorate General of Civil were therefore, left with no private carrier in its found that 'opaque fares' Aviation (DGCA) cited them choice. IndiGo can't be schemes. "The ailing were not offered by any por- as a violation of rules. In a seen supporting a blatant carrier's fares appear right tal. No airline is part of it," 150 Afghan schoolgirls statement issued on Tues- violation of the law and on top with most other air- Bhushan said. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial Board

June 2021 Volume 27, Number 6S AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial board Editor-in-Chief Pauline M. Camacho, MD, FACE Suleiman Mustafa-Kutana, BSC, MB, CHB, MSC Maywood, Illinois, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, FACE Atlanta, Georgia, United States Andrea Coviello, MD, MSE, MMCi Karel Pacak, MD, PhD, DSc Durham, North Carolina, United States Bethesda, Maryland, United States Associate Editors Natalie E. Cusano, MD, MS Amanda Powell, MD Maria Papaleontiou, MD New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Tobias Else, MD Gregory Randolph, MD Melissa Putman, MD Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vahab Fatourechi, MD Daniel J. Rubin, MD, MSc Harold Rosen, MD Rochester, Minnesota, United States Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ruth Freeman, MD Joshua D. Safer, MD Nicholas Tritos, MD, DS, FACP, FACE New York, New York, United States New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Rajesh K. Garg, MD Pankaj Shah, MD Boston, Massachusetts, United States Staff Rochester, Minnesota, United States Eliza B. Geer, MD Joseph L. Shaker, MD Paul A. Markowski New York, New York, United States Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States CEO Roma Gianchandani, MD Lance Sloan, MD, MS Elizabeth Lepkowski Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Lufkin, Texas, United States Chief Learning Officer Martin M. Grajower, MD, FACP, FACE Takara L. Stanley, MD Lori Clawges The Bronx, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Senior Managing Editor Allen S. Ho, MD Devin Steenkamp, MD Corrie Williams Los Angeles, California, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Peer Review Manager Michael F. -

Bollywood Star Kangana Ranaut Takes on the Media with Panache. P4-5

Community Community Toastmasters World District renowned DJ P7116-Qatar P16 and American emerges as the electronic music topmost district in the producer Marshmello world for the 2018-19 to perform at QNCC ranking. today. Thursday, July 25, 2019 Dhul-Qa’da 22, 1440 AH Doha today: 320 - 390 SStartar wwarsars COVER Bollywood star Kangana Ranaut takes STORY on the media with panache. P4-5 REVIEW SHOWBIZ Tarnished gold lurking Casting directors in the Hollywood hills. play big part today. Page 14 Page 15 2 GULF TIMES Thursday, July 25, 2019 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.29am Shorooq (sunrise) 4.58am Zuhr (noon) 11.42am Asr (afternoon) 3.08pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.25pm Isha (night) 7.55pm USEFUL NUMBERS Arsass Karaan opinion about life. understand their families but are given a DIRECTION: Gippy Grewal The elderly men believe spending time week to accomplish this. CAST: Gippy Grewal, Gurpreet with each other and communicating may Will Sehaj and Magic manage to fi nd Ghuggi, Meher Vij help bridge their gap. But each time the a common thread for the three diff ering SYNOPSIS: Ardass Karaan explores family plans to spend time with each generations to live together in harmony? the generation gap faced by families. other they end up arguing. How will they use Ardaas (prayer) to Emergency 999 Three elderly men live in Canada with One day, the elderly gentlemen come convey their message about life? Worldwide Emergency Number 112 their families and realise that each across Sehaj and Magic who are full Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 generation -

Indian Films on Partition of India

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Manoj Sharma, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 3, pp. 492 - 501 Date of Publication: 15th December, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.33.492501 This paper can be cited as: Sharma, M. (2017). Cinematic Representations of Partition of India. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 492-501. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF PARTITION OF INDIA Dr. Manoj Sharma Assistant Professor, Modern Indian History, Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 – India [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The partition of India in August 1947 marks a watershed in the modern Indian history. The creation of two nations, India and Pakistan, was not only a geographical division but also widened the chasm in the hearts of the people. The objective of the paper is to study the cinematic representations of the experiences associated with the partition of India. The cinematic portrayal of fear generated by the partition violence and the terror accompanying it will also be examined. Films dealing with partition have common themes of displacement of thousands of masses from their homelands, being called refugees in their own homeland and their struggle for survival in refugee colonies. They showcase the trauma of fear, violence, personal pain, loss and uprooting from native place. -

Looking at Popular Muslim Films Through the Lens of Genre

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, Vol. IX, No. 1, 2017 0975-2935 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v9n1.17 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V9/n1/v9n117.pdf Is Islamicate a Genre? Looking at Popular Muslim Films through the Lens of Genre Asmita Das Department of Film Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. ORCID: 0000-0002-7307-5818. Email: [email protected] Received February 25, 2017; Revised April 9, 2017; Accepted April 10, 2017; Published May 7, 2017. Abstract This essay engages with genre as a theory and how it can be used as a framework to determine whether Islamicate or the Muslim films can be called a genre by themselves, simply by their engagement with and representation of the Muslim culture or practice. This has been done drawing upon the influence of Hollywood in genre theory and arguments surrounding the feasibility / possibility of categorizing Hindi cinema in similar terms. The essay engages with films representing Muslim culture, and how they feed into the audience’s desires to be offered a window into another world (whether it is the past or the inner world behind the purdah). It will conclude by trying to ascertain whether the Islamicate films fall outside the categories of melodrama (which is the most prominent and an umbrella genre that is represented in Indian cinema) and forms a genre by itself or does the Islamicate form a sub-category within melodrama. Keywords: genre, Muslim socials, socials, Islamicate films, Hindi cinema, melodrama. 1. Introduction The close association between genre and popular culture (in this case cinema) ensured generic categories (structured by mass demands) to develop within cinema for its influence as a popular art. -

Été Indien 10E Édition 100 Ans De Cinéma Indien

Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien 9 Les films 49 Les réalisateurs 10 Harishchandrachi Factory de Paresh Mokashi 50 K. Asif 11 Raja Harishchandra de D.G. Phalke 51 Shyam Benegal 12 Saint Tukaram de V. Damle et S. Fathelal 56 Sanjay Leela Bhansali 14 Mother India de Mehboob Khan 57 Vishnupant Govind Damle 16 D.G. Phalke, le premier cinéaste indien de Satish Bahadur 58 Kalipada Das 17 Kaliya Mardan de D.G. Phalke 58 Satish Bahadur 18 Jamai Babu de Kalipada Das 59 Guru Dutt 19 Le vagabond (Awaara) de Raj Kapoor 60 Ritwik Ghatak 20 Mughal-e-Azam de K. Asif 61 Adoor Gopalakrishnan 21 Aar ar paar (D’un côté et de l’autre) de Guru Dutt 62 Ashutosh Gowariker 22 Chaudhvin ka chand de Mohammed Sadiq 63 Rajkumar Hirani 23 La Trilogie d’Apu de Satyajit Ray 64 Raj Kapoor 24 La complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) de Satyajit Ray 65 Aamir Khan 25 L’invaincu (Aparajito) de Satyajit Ray 66 Mehboob Khan 26 Le monde d’Apu (Apur sansar) de Satyajit Ray 67 Paresh Mokashi 28 La rivière Titash de Ritwik Ghatak 68 D.G. Phalke 29 The making of the Mahatma de Shyam Benegal 69 Mani Ratnam 30 Mi-bémol de Ritwik Ghatak 70 Satyajit Ray 31 Un jour comme les autres (Ek din pratidin) de Mrinal Sen 71 Aparna Sen 32 Sholay de Ramesh Sippy 72 Mrinal Sen 33 Des étoiles sur la terre (Taare zameen par) d’Aamir Khan 73 Ramesh Sippy 34 Lagaan d’Ashutosh Gowariker 36 Sati d’Aparna Sen 75 Les éditions précédentes 38 Face-à-face (Mukhamukham) d’Adoor Gopalakrishnan 39 3 idiots de Rajkumar Hirani 40 Symphonie silencieuse (Mouna ragam) de Mani Ratnam 41 Devdas de Sanjay Leela Bhansali 42 Mammo de Shyam Benegal 43 Zubeidaa de Shyam Benegal 44 Well Done Abba! de Shyam Benegal 45 Le rôle (Bhumika) de Shyam Benegal 1 ] Je suis ravi d’apprendre que l’Auditorium du musée Guimet organise pour la dixième année consécutive le festival de films Été indien, consacré exclusivement au cinéma de l’Inde. -

Fezana Journal

PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Fall/September 2010, PAIZ 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, 3 Message from the President www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 9 Financial Report Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 34 YLEP UPDATE Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] 37 Global Health Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla 97 In The News Subscription Managers: Kershaw Khumbatta : [email protected] 112 Interfaith /Interalia Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected] WINTER 2010 115 North American Mobeds’ Council SHAHNAMEH: THE SOUL OF IRAN GUEST EDITOR TEENAZ JAVAT 120 Personal Profiles SPRING 2011 124 Letters to the editor ZARATHUSHTI PHILANTHROPY GUEST EDITOR DR MEHROO M. PATEL 129 Milestones Photo on cover: 141 Between the Covers 147 Business Mehr- Avan – Adar 1379 AY (Fasli) Ardebehesht – Khordad – Tir 1380 AY (Shenshai) Khordad - Tir – Amordad 1380 AY (Kadimi) Cover design Opinions expressed in the FEZANA Journal do not necessarily reflect the views of Feroza Fitch of FEZANA or members of this publications’s editorial board Lexicongraphics Please note that past issues of The Journal are available to the public, both in print and online through our archive at fezana.org. -

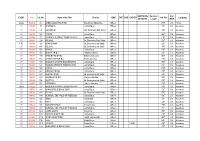

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

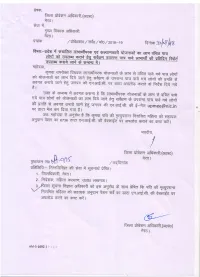

2018083185.Pdf

tuin esa losZ{k.kksaijkUr fujfJr efgyk isa'ku ;kstuk ds efgykvksa dh lwpuk viyksM fd;s tkus dk izk:i%& vvv kkk Js.kh ¼v0tk0 bbb dz0 xzke iapk;r dk fodkl [k.M dk tuin dk Z-Z- vkosfndk dk uke ifr dk uke v0t0tk0@f Z-Z- la0la0la0 uke uke uke ,,, iNM+k½ QQQ --- lll S 1 SUMAN MEWARAM 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 2 SHEELA MUNNALAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U N 3 MAYA DEVI HARI SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT - T P 4 BABITA VIRENDRA 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 5 SHAKUNTALA PREETAM SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 6 SHIMLA JAIBHAGWAN 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 7 LAKHMEERI MADAN PAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 8 KIRAN CHAMAN LAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U S 9 SANTOS PAPPU SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC B P 10 SHOBHA DEVI MOOLCHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 11 KISHNO KAILASH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U 12 MADHU BHAGWAN DAS 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC - U 13 KAUSHALYA MUNNA LAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 14 RAMMI NEEPAK 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U S 15 SHANTI DEVI ARVIND KUMAR 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 16 KAMLESH RAMCHANDRA SAINI 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 17 GYANWATI DULICHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 18 BALA DEVI SURESH KUMAR 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT - U B 19 MURTI BAUDH SHYAM SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC K B 20 JAIWATI MANGEY RAM 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC K P 21 ASHA SUBHASH CHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC U P 22 BALESHWARI GIRIRAJ SINGH -

Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: a Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2016-4 Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: A Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography Giovanna Rampazzo Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Rampazzo, G. (2016) Formation of Indian cinema in Dublin: a participatory researcher-fan ethnographyDoctoral Thesis. Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7C010 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: A Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography Giovanna Rampazzo, MPhil This Thesis is submitted to the Dublin Institute of Technology in Candidature for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2016 Centre for Transcultural Research and Media Practice School of Media College of Arts and Tourism Supervisors: Dr Alan Grossman Dr Anthony Haughey Dr Rashmi Sawhney Abstract This thesis explores emergent formations of Indian cinema in Dublin with a particular focus on globalising Bollywood film culture, offering a timely analysis of how Indian cinema circulates in the Irish capital in terms of consumption, exhibition, production and identity negotiation. The enhanced visibility of South Asian culture in the Irish context is testimony to on the one hand, the global expansion of Hindi cinema, and on the other, to the demographic expansion of the South Asian community in Ireland during the last decade.