Production Functions for Chickpea, Field Pea, and Lentil in the Central Great Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soy Free Diet Avoiding Soy

SOY FREE DIET AVOIDING SOY An allergy to soy is common in babies and young children, studies show that often children outgrow a soy allergy by age 3 years and the majority by age 10. Soybeans are a member of the legume family; examples of other legumes include beans, peas, lentils and peanut. It is important to remember that children with a soy allergy are not necessarily allergic to other legumes, request more clarification from your allergist if you are concerned. Children with a soy allergy may have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, difficulty breathing, and or a skin reaction after eating or drinking soy products. These symptoms can be avoided by following a soy free diet. What foods are not allowed on a soy free diet? Soy beans and edamame Soy products, including tofu, miso, natto, soy sauce (including sho yu, tamari), soy milk/creamer/ice cream/yogurt, soy nuts and soy protein, tempeh, textured vegetable protein (TVP) Caution with processed foods - soy is widely used manufactured food products – remember to carefully read labels. o Soy products and derivatives can be found in many foods, including baked goods, canned tuna and meat, cereals, cookies, crackers, high-protein energy bars, drinks and snacks, infant formulas, low- fat peanut butter, processed meats, sauces, chips, canned broths and soups, condiments and salad dressings (Bragg’s Liquid Aminos) USE EXTRA CAUTION WITH ASIAN CUISINE: Asian cuisine are considered high-risk for people with soy allergy due to the common use of soy as an ingredient and the possibility of cross-contamination, even if a soy-free item is ordered. -

Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata) Plant Guide

Plant Guide prevention and weed suppression. Allelopathic COWPEA compounds in the plant may help to suppress weeds (Clark, 2007). It has also been used successfully as Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. groundcover in orchards and intercropped with cash crops Plant Symbol = VIUN such as cotton. Contributed by: USDA NRCS Cape May Plant Materials Wildlife: Cowpea is eaten by deer as forage, and is Center, Cape May, NJ commonly used in food plots for deer. A variety of birds, including wild turkey, eat the seeds and the plant can be used by quail as cover. Some varieties of cowpea are used specifically for wildlife purposes (Ball et al., 2007). Ethnobotany: Cowpea has been a staple crop and important protein source for many cultures since the Roman Empire. It was the most commonly cultivated bean used for human consumption in the Old World (Allen and Allen, 1981). Roman writers such as Pliny referred to it as phaseolus. Thomas Jefferson is credited with first using the name cowpea. Today the crop is still widely popular, and good harvests are critical to ensure adequate levels of protein in the diets of populations in India and East Asia (Allen and Allen, 1981). Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata). (Photo by Christopher Sheahan, USDA- NRCS, Cape May Plant Materials Center) Status Cowpea is an introduced species in the United States. It is Alternate Names native to tropical and subtropical regions. It can grow Alternate Common Names: blackeyed pea, field pea, both wild and cultivated. Please consult the PLANTS southern pea, crowder pea, caupi, catjang, yardlong bean Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or Alternate Scientific Names: endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland Vigna sinensis (L.) Savi, indicator values). -

Adaptation of Beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) to Low Phosphorus Availability Jonathan P

Adaptation of Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) to Low Phosphorus Availability Jonathan P. Lynch1 Department of Horticulture, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 Stephen E. Beebe Bean Program, International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Apartado Aéveo 6713, Cali, Colombia Phosphorus availability in native soils is seldom adequate for has been carried out in Colombia (Thung, 1990; Youngdahl, 1990), optimal plant growth. Of the macronutrients, K, Ca, Mg, and S are not Brazil [Salinas, 1978; International Center for Tropical Agriculture uncommon in the earth’s crust and in fresh water (Epstein, 1972); N is (CIAT), unpublished data], Costa Rica (Corella, unpublished data), abundant in the atmosphere and is present in most soil solutions in and Nicaragua (Tapia, 1987). In at least one case, recommendations millimolar concentrations. In contrast, P is present in soil solution and for P applications were tailored cultivar by cultivar, from 0 to 42 kg P/ fresh water in only micromolar concentrations (Rendig and Taylor, ha, depending on the P requirements of the specific genotype. The 1989), in large part because P is commonly bound to many soil Brazilian cultivar Carioca is broadly adapted to low-P conditions, and constituents that make it unavailable or only sparingly available to is extremely responsive to added P (Thung, 1990). These traits plants (Sample et al., 1980). An additional problem is that the P cycle undoubtedly contribute to the fact that ‘Carioca’ is the most widely in most terrestrial ecosystems is open-ended and tends toward deple- grown cultivar in Brazil (Janssen et al., 1992). In Rwanda, a climbing tion, unlike the N cycle, in which atmospheric pools provide continual bean from Mexico, G2333, has gained great popularity among small inputs to soil pools (Stevenson, 1986). -

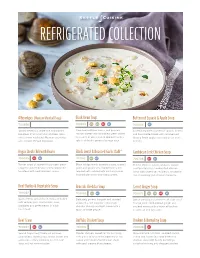

KC Refrigerated Product List 10.1.19.Indd

Created 3.11.09 One Color White REFRIGERATEDWhite: 0C 0M 0Y 0K COLLECTION Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Black Bean Soup Butternut Squash & Apple Soup 700856 700820 VN VG DF GF 700056 GF Savory meatballs, white rice and vibrant Slow-cooked black beans, red peppers, A blend of puréed butternut squash, onions tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken stock roasted sweet corn and diced green chilies and handcrafted stock with caramelized infused with traditional Mexican aromatics in a purée of vine-ripened tomatoes with a Granny Smith apples and a pinch of fresh and a touch of fresh lime juice. splash of fresh-squeezed orange juice. nutmeg. Angus Steak Chili with Beans Black Lentil & Roasted Garlic Dahl* Caribbean Jerk Chicken Soup 700095 DF GF 701762 VG GF 700708 DF GF Tender strips of seared Angus beef, green Black beluga lentils, sautéed onions, roasted Tender chicken, sweet potatoes, carrots peppers and red beans in slow-simmered garlic and ginger slow-simmered in a rich and tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken tomatoes with Southwestern spices. tomato broth, infused with warming spices, stock with white rice, red beans, traditional finished with butter and heavy cream. jerk seasoning and a hint of molasses. Beef Barley & Vegetable Soup Broccoli Cheddar Soup Carrot Ginger Soup 700023 700063 VG GF 700071 VN VG DF GF Seared strips of lean beef and pearl barley Delicately puréed broccoli and sautéed Sweet carrots puréed with fresh-squeezed with red peppers, mushrooms, peas, onions in a rich blend of extra sharp orange juice, hand-peeled ginger and tomatoes and green beans in a rich cheddar cheese and light cream with a sautéed onions with a touch of toasted beef stock. -

Southern Peas

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA6020 Home Gardening Series Southern Peas Craig R. Andersen Environment Associate Professor and Extension Specialist - Light Soil Vegetables Fertility pH Temperature Moisture – sunny – welldrained loam Culture– medium to light – 5.8 to 7.0 Planting – warm season Spacing – average to drought Hardiness resistant Cultural Practices Fertilizer Soils Southern Peas – Vigna unguiculata– seed 1 inch deep – 2 x 24 inches – tender annual – light Southern peas adapt to many soil types; medium fertility with pH of 5.8 to 7.0 is desirable. High fertility proPlanting Time The southern pea, also known as duces excessive vine growth and poor the cowpea, is thought to have origi yields. Nfixing bacteria inoculants nated in Africa, where it has been may increase yield especially in soils eaten for centuries. It traveled to where peas have not been grown. Egypt as long as 3,000 years ago and was common to the European and Asian diets. Southern peas were prob ably brought to the West Indies in the Plant southern peas after the soil 17th century. They later became a is thoroughly warm (62 degrees F common food in the United States. or greater) in late spring or early One of the more popular ways of cook summer. This vegetable is very toler ing blackeyed peas is a dish called Spacingant to hot weather and can be planted and Depth of Planting “Hoppin’ John,” a traditional African throughout the summer with very American dish served on New Year’s good results. For fall planting, plant Day for good luck. -

Product List Winter 2020/21 2 Winter 2020/21 Winter 2017 3

Product List Winter 2020/21 2 Winter 2020/21 Winter 2017 3 Contents Large and Small meals Large and Small Meals Textured Modified A huge selection of mains, soups, Savoury Pastries 04 Level 3 (Liquidised) 22 sides and desserts – created to Breakfast 04 Level 4 (Puréed) 22 sustain and nourish patients. Soups 05 Level 4 (Purée Petite) 25 Main meals – Meat Level 5 (Minced & Moist) 26 • Beef 06 Level 6 (Soft & Bite-Sized) 27 • Poultry 06 • Pork 08 • Other Meat 08 Special Diets • Lamb & Mutton 09 Gluten free 29 Main Meals - Fish 09 Free From 30 Main Meals - Vegetarian 10 Mini Meals Extra 31 Sides Energy dense 32 • Accompaniments 11 Low & Reduced Sugars Individual Desserts 32 • Vegetables 12 Finger Foods 33 • Potatoes and Rice 13 Desserts Ethnic Meals • Hot Desserts 14 Kosher Meals 35 • Cold Desserts 16 Kosher Desserts 35 • Cakes 16 Caribbean & West Indian Meals 36 Asian Halal Meals 37 CarteChoix Asian Halal Vegetarian Meals 38 Main meals – Meat • Beef 18 Dietary Codes 39 • Lamb 18 • Poultry 18 • Pork 18 Main Meals - Fish 18 Main Meals - Vegetarian 18 Main Meals - iWave Recommended 19 Desserts • Hot desserts 19 Making food that tastes great and aids patient recovery has been our mission from day one. It’s what our registered dietitian and team of qualified chefs work tirelessly for. Whatever a patient’s dietary needs, ethnic preference or taste, it’s about offering them something good to eat. Our Dietitian, Emily Stuart, is a healthcare expert as well as a member Minced Beef Hotpot : 324112 of the BDA 4 Winter 2020/21 Large and Small Meals Winter -

Extension Methods and Their Implications on Crop Yield in a Maize

Extension Methods and their Implications on Crop Yield in a Maize – Legume Conservation Agriculture Project in Zambia Kafula Chisanga1, Nswana Kafwamfwa1, Petan Hamazakaza2, Mulundu Mwila3, Joy Sinyangwe4, Olipa Lungu5 1Zambia Agriculture Research Institute (ZARI), Mochipapa Research Station, P.O. Box 630090, Choma, 2Zambia Agriculture Research Institute, Kabwe Research Station, P.O. Box 80908 Kabwe, 3Zambia Agriculture Research Institute, Msekera Research Station, P.O. Box 510046 Chipata, 4Department of Agriculture, Mulungushi House, 10101, Lusaka, 5University of Zambia, Department of Soil Science, P.O. Box 32379 Lusaka (Corresponding author: [email protected]) Introduction Methods Results Figure # 1 Comparison of mean maize yield results across sites (kg/ha) for two seasons; • Conservation Agriculture (CA) is one of the Table #1 Maize yield results across sites (kg/ha) for 2014/15 and 2015/16 based on extension • Participatory Action Research (PAR) sustainable intensification technologies that is 2014/15 season delivery approach through consensus building Treatments Chipata Monze Mpongwe increasingly promoted by various international 5000 (T1) PP + M + 2811 4341 3619 meetings with farmers and key partner 4500 research centres, international non- FRF organizations (T2) PP + M + D 1605 3665 2700 4000 governmental organizations (NGOs), faith Comp 3500 (T3) PP + M + 2219 3480 2577 3000 based organizations and governments of HRF • Field demonstrations of crops; maize, 2500 (T4) GN + M + 3038 4469 3204 southern Africa among others 2000 -

Peas Lettuce Radish Basil Pot Blueberries Broccoli Carrots

Gazette Know Your Farmer … Know Your Food Wightmans Farm CSA 2015 Week 4 Welcome to week 4! If you are a Tues or Fri pick up (at the farm) you do NOT have to email or THE call if you are picking up the next day. However, please pick up BEFORE 12 Wednesday or Sat- urday. FLOWERS & HERBS! Unfortunately we still have at least 2 more weeks. Mother Nature was cruel this winter and they are not there yet…(for PYO) the herbs may be ready earlier, I will let you know one week prior to picking! Our Own Broccoli Cheese Yumminess! 1 large onion, chopped Peas 3 tablespoons vegetable oil Our Own 4 eggs, lightly beaten 4 cups chopped fresh broccoli, cooked Lettuce 2 cups (8 ounces) shredded mozzarella cheese Our Own 1 carton (15 ounces) ricotta cheese 1/3 cup grated Parmesan cheese Radish 1/4 teaspoon salt Dash ground nutmeg Our Own 1 unbaked pie pastry (9 inches) Cucumber In a skillet, sauté onion in oil until tender, about 5 minutes. Transfer to a large bowl; add eggs, broccoli, cheeses, salt and nutmeg. Pour into pie shell. Bake at 350° for 50-55 minutes or until Our Own a knife inserted near the center comes out clean. Yield: 6-8 servings. Broccoli & Carrot Slaw Basil Pot Ingredients: 2 Carrots Blueberries 1 small head Broccoli (with Stem) 1/4 cup Red Onion, finely chopped 1/2 cup Raisins (soaked in warm water before use) Broccoli 1/4 cup dry roasted Pumpkin Seeds Squeeze of lemon juice Carrots For the Greek Yogurt mayo: 2/3 cup nonfat plain Greek Yogurt 1/2-1 tbsp dijon mustard Squash 1/2 tsp garlic powder salt and pepper, to taste Sprouts 1 tbsp freshly squeezed lemon juice Wightman’s Farms1111 Mount Kemble Ave, Morristown NJ Instructions fin topping. -

Water Deficit Effects on Root Distribution of Soybean, Field Pea and Chickpea

Field Crops Research 97 (2006) 248–253 www.elsevier.com/locate/fcr Water deficit effects on root distribution of soybean, field pea and chickpea J.G. Benjamin *, D.C. Nielsen USDA-ARS, Central Great Plains Research Station, 40335 Co. Rd. GG, Akron, CO 80720, USA Received 23 September 2005; accepted 15 October 2005 Abstract Cropping diversity in the central Great Plains of the United States could be increased by including suitable legumes in crop rotations. Water is limiting to all crops grown in this region and agronomic crops frequently experience water deficit stress during their life cycle. The ability of a plant to change its root distribution to exploit deeper stored soil water may be an important mechanism to avoid drought stress. An experiment was conducted to examine legume root system response to water deficit stress. Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), field pea (Pisum sativum L.), and soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) were grown at two water regimes: under natural rainfall conditions and irrigated to minimize water deficit stress. Root distributions for each species were measured at 0.23 m depth intervals to a depth of 1.12 m directly beneath the plants at the late bloom and mid pod fill growth stages. Roots were washed free of soil and were separated from soil debris by hand. Root surface area measurements were made and root weights were recorded for each depth interval. Water deficit did not affect the relative soybean root distribution. Approximately 97% of the total soybean roots were in the surface 0.23 m at both sampling times and under both water regimes. -

Structural Profile of the Pea Or Bean Family

Florida ECS Quick Tips July 2016 Structural Profile of the Pea or Bean Family The Pea Family (Fabaceae) is the third largest family of flowering plants, with approximately 750 genera and over 19,000 known species. (FYI – the Orchid Family is the largest plant family and the Aster Family ranks second in number of species.) I am sure that you are all familiar with the classic pea flower (left). It, much like the human body, is bilaterally symmetrical and can be split from top to bottom into two mirror-image halves. Botanists use the term zygomorphic when referring to a flower shaped like this that has two different sides. Zygomorphic flowers are different than those of a lily, which are radially symmetrical and can be split into more than two identical sections. (These are called actinomorphic flowers.) Pea flowers are made up of five petals that are of different sizes and shapes (and occasionally different colors as well). The diagram at right shows a peanut (Arachis hypogaea) flower (another member of the Pea Family), that identifies the various flower parts. The large, lobed petal at the top is called the banner or standard. Below the banner are a pair of petals called the wings. And, between the wings, two petals are fused together to form the keel, which covers the male and female parts of the flower. Because of the resemblance to a butterfly, pea flowers are called papilionaceous (from Latin: papilion, a butterfly). However, there is group of species in the Pea Family (a subfamily) with flowers like the pride-of-Barbados or peacock flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima) shown to the left. -

Spatial Rooting Patterns of Gliricidia, Pigeon Pea and Maize Intercrops and Effect on Profile Soil N and P Distribution in Southern Malawi

African Journal of Agricultural Research Vol. 4 (4), pp. 278-288, April 2009 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR ISSN 1991-637X © 2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Spatial rooting patterns of gliricidia, pigeon pea and maize intercrops and effect on profile soil N and P distribution in southern Malawi Wilkson Makumba1*, Festus K. Akinnifesi2 and Bert H. Janssen3 1Department of Agricultural Research Services, Chitedze Agricultural Research Station, P. O. Box 158, Lilongwe, Malawi. 2World Agroforestry Centre, Chitedze Agricultural Research Station, P. O. Box 30798, Lilongwe. Malawi. 3Wageningen University and Research Centre, Department of Environmental Sciences, P. O. Box 8005, 6700 EC Wageningen, The Netherlands. Accepted 27 March, 2009 The concept of competition or complementarity between tree and crop roots for below ground resources have been a major debate in simultaneous systems. Root studies were conducted in three cropping systems, namely: sole maize, pigeon pea/maize intercropping and Gliricidia sepium (Gliricidia)/maize intercropping, with the objective of understanding the potential for competition or otherwise. Pigeon pea and maize root development was monitored at 21, 42 and 63 days after planting (DAP). Also soil mineral N and Olsen P were assessed along the soil profile up to 200 cm depth. Maize roots developed faster than those of pigeon pea during the first 42 days after planting and there was little overlapping of maize and pigeon pea roots. However, the roots of both pigeon pea and maize had its peaks at 63 DAP, suggesting potential competition during reproductive growth stage of maize. In Gliricidia/maize intercropping, maize had the highest root density averaging 1.02 cm cm-3 in the top 0 -4 0 cm soil layer, whereas gliricidia had lower root length density (0.38 cm cm-3) in the top 0 - 40 cm soil layer compared to 0.65 cm cm-3 in the subsoil (40 - 100 cm). -

Summer Chicken. Feta, Radish and Pea Salad

Summer Chicken. Feta, Radish and Pea Salad This delicious salad is a different take on a normal chicken salad and sure to surprise and delight your friends. 4 chicken breasts, grilled and sliced 1 ½ pounds of sugar snap peas 3 tablespoons of extra virgin olive oil 1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice ½ teaspoon ground sumac 1 bunch radishes thinly sliced 4 ½ ounces of feta, crumbled 2 tablespoons of chopped fresh mint 1 tablespoon of chopped fresh parsley. Cook sugar snap peas in boiling water for 2-3 minutes, drain, refresh with cold water (to keep the color) and drain again and dry with kitchen towel. Halve lengthways. Whish together oil, lemon juice and sumac in a small bowl. Toss peas, radishes and feta in large bowl: add chicken and dressing and toss gently to coat. Season to taste and garnish with the mint and parsley. Drink with Stone House Grenache Blanc or Stone House Viognier. Roasted Ratatouille If you’re a vegetarian or just love vegetables this is a non-traditional version and is a delicious accompaniment to grilled fish, lamb or beef. 2 medium size zucchini 1 eggplant, shopped into 1 inch squares 1 pound cherry tomatoes, skinned 1 red pepper, deseeded and chopped into 1 inch squares 1 yellow pepper. Deseeded and chopped into 1 inch squares I medium size onion peeled and chopped into 1 inch squares 2 large cloves of garlic, finely chopped Handful of fresh basil leaves ¼ cup olive oil Salt and freshly ground pepper Prepare zucchini and eggplant in advance, leaving their skins on and cutting them into 1 inch squares – approximately.