The Successful Integration of Food & Beverage Within Retail Real Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Villa Breakfast

In Villa Breakfast For your convenience you can scan these QR codes to see our menu in your preferred language Chinese Russian Freshly Squeezed Juices THB 400 Orange Watermelon Carrot Thai Pomelo Melon Tomato Mango Papaya Cucumber Pineapple Apple Mixed Fruit Smoothies THB 450 Strawberry Peach Exotic Fruit Banana Mango Mixed Fruit Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). Seasonal Fresh Cut Fruits THB 380 Choose Your 5 Favourite Fruits From Our List Mango Longan* Orange Green Apple Papaya Thai Pomelo Red Apple Passion Fruit Watermelon Green Grape Lychees* Black Grape Pineapple Pomegranate Bananas Rambutan* Mangosteen* Dragon Fruit Mandarin Rose Apple Guava *Subject to seasonal availability Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). From The Bakery THB 890 Basket Freshly Baked Bread Croissants, Danish Pastry, Rolls, Toast, and Muffins Selection of Homemade Jams French Butter, Vanilla Butter Danish Collection THB 690 Freshly Baked Danish Pastries Home Style Muesli THB 380 Choose Your Favourite Traditional Bircher Muesli Muesli (GF) Berry Muesli Oatmeal Artisan Cheese Selection If you have a cheese preference please speak to your waiter Homemade Jams and Preserves Strawberry Jam Raspberry Jam Papaya Jam Passion Fruit Jam Apple Jam Mango Jam Kiwi Jam Coconut Jelly Apricot Jelly Mandarin Marmalade Pineapple Marmalade Pumpkin Marmalade Lemon Marmalade Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). -

Ingrouille, Kristina Title: Effect of Caffeinated Beverages Upon Breakfast Meal Consumption of University of Wisconsin-Stout Undergraduate Students

1 Author: Ingrouille, Kristina Title: Effect of Caffeinated Beverages upon Breakfast Meal Consumption of University of Wisconsin-Stout Undergraduate Students The accompanying research report is submitted to the University of Wisconsin-Stout, Graduate School in partial completion of the requirements for the Graduate Degree/ Major: MS in Food and Nutritional Sciences Research Advisor: Carol Seaborn, Ph.D. Submission Term/Year: Spring, 2013 Number of Pages: 51 Style Manual Used: American Psychological Association, 6th edition I understand that this research report must be officially approved by the Graduate School and that an electronic copy of the approved version will be made available through the University Library website I attest that the research report is my original work (that any copyrightable materials have been used with the permission of the original authors), and as such, it is automatically protected by the laws, rules, and regulations of the U.S. Copyright Office. My research advisor has approved the content and quality of this paper. STUDENT: NAME Kristina Ingrouille DATE: May 14, 2013 ADVISOR: (Committee Chair if MS Plan A or EdS Thesis or Field Project/Problem): NAME Carol Seaborn DATE: May 14, 2013 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---- This section for MS Plan A Thesis or EdS Thesis/Field Project papers only Committee members (other than your advisor who is listed in the section above) 1. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: 2. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: 3. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---- This section to be completed by the Graduate School This final research report has been approved by the Graduate School. Director, Office of Graduate Studies: DATE: 2 Ingrouille, Kristina. -

Differences in Energy and Nutritional Content of Menu Items Served By

RESEARCH ARTICLE Differences in energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK chain restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross-sectional study ☯ ☯ Dolly R. Z. TheisID *, Jean AdamsID Centre for Diet and Activity Research, MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United a1111111111 Kingdom a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Background OPEN ACCESS Poor diet is a leading driver of obesity and morbidity. One possible contributor is increased Citation: Theis DRZ, Adams J (2019) Differences consumption of foods from out of home establishments, which tend to be high in energy den- in energy and nutritional content of menu items sity and portion size. A number of out of home establishments voluntarily provide consumers served by popular UK chain restaurants with with nutritional information through menu labelling. The aim of this study was to determine versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross- whether there are differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served by sectional study. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0222773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222773 popular UK restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling. Editor: Zhifeng Gao, University of Florida, UNITED STATES Methods and findings Received: February 8, 2019 We identified the 100 most popular UK restaurant chains by sales and searched their web- sites for energy and nutritional information on items served in March-April 2018. We estab- Accepted: September 6, 2019 lished whether or not restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling by telephoning head Published: October 16, 2019 offices, visiting outlets and sourcing up-to-date copies of menus. -

Minutes of Regular Meeting, Board of Education, School District #225, Cook County, Illinois, December 15, 2014

1 12/15/14 MINUTES OF REGULAR MEETING, BOARD OF EDUCATION, SCHOOL DISTRICT #225, COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS, DECEMBER 15, 2014 A regular meeting of the Board of Education, School District No. 225 was held on Monday, December 15, 2014, at approximately 7:02 p.m. at Glenbrook South High School Student Center, pursuant to due notice of all members and the public. The president called the meeting to order. Upon calling of the roll, the following members answered present: Boron, Doughty, Hanley, Martin, Shein, Wilkas Absent: Taub Also present: Bretag, Finan (arrived 7:29 p.m.), Freund (arrived 8:09 p.m.), Geallis, Geddeis, Pearson, Pryma, Riggle, Siena, Swanson, Wegley, Whisler, Williamson, Petrarca (attorney – arrived 8:00 p.m.) APPROVAL OF AGENDA FOR THIS MEETING Motion by Mr. Boron, seconded by Mr. Doughty to approve the agenda for this meeting. Upon calling of the roll: aye: Boron, Doughty, Hanley, Martin, Shein, Wilkas nay: none Motion carried 6-0. STUDENTS AND STAFF WHO EXCEL Ms. Geddeis recognized the GBS Oracle editorial board for winning the Pacemaker award. The Pacemaker recognizes writing, design graphics, photography, illustrations and editorial leadership. The GBS Oracle is one of only six newspapers in the entire nation to receive this honor and a first in GBS history. Mr. Marshall Harris (GBS) thanked the Board for recognizing the hard work of the students and for the great opportunity that they afford the students. The students introduced themselves and their position on the paper. 2 12/15/14 Dr. Riggle stated how proud he is of the students’ hard work and noted what a great paper they put out. -

Egan Dining Hall Laker Inn Food Court the Coffee Bar

THE COFFEE BAR AT THE BOOKSTORE EGAN DINING HALL Egan Dining Hall is an All-You-Care-to-Eat dining facility. That means that The Coffee Bar proudly brews Starbucks® coffee and other specialty, you can eat whatever you want, as many times as you want! seasonal drinks. Enjoy fresh-baked pastries, a variety of sandwiches, snacks, and candies for those mid-day cravings, and local bagels every Monday Filled with fresh, house-made, wholesome foods, Egan Dining Hall is through Friday. guaranteed to satisfy your dining needs. Have your choice of a daily selection of homestyle entrées: a deli sandwich stacked high with freshly HOURS sliced meat and cheese, a pizza baked in our open brick oven featuring Monday through Thursday 7:30 a.m. – 8:00 p.m. made-from-scratch dough, or a specialty meal hand-crafted to your Friday 7:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. liking at our chef-attended display cooking station. Begin your day with a Saturday 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. steaming cup of coffee or a late night latte from Starbucks®, located directly Sunday 2:00 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. inside the entrance of Egan Hall. CONVENIENCE STORE AT WARDE HALL Plus…don’t forget to save room for dessert! To top off each meal, you can All students are welcome at the Convenience Store in Warde Hall for a fresh choose from a variety of enticing desserts, prepared for you by our talented array of sandwiches, salads and wraps to go, along with snacks, candies, bakers, or choose from a variety of Perry’s® Ice Cream. -

Developer Du Jour: Food Halls Popping up Across Metro Atlanta

Developer du jour: Food halls popping up across metro Atlanta March 16, 2018 Boosted by the success of Krog Street and Ponce City markets, new food halls are popping up across metro Atlanta. At least five projects are planned, stretching from Midtown Atlanta to Forsyth County, as developers seek to bring energy to their projects through these new food concepts that feature several restaurants and vendors around a central gathering space. “On every developer’s site plan where it used to show a grocery store, it now shows a food hall,” said George Banks, who runs retail consulting and development firm Revel with partner Kristi Rooks. Revel is about to break ground on “The Daily” in Alpharetta that will bundle six restaurants around a central courtyard at the former site of The Varsity. “It’s a high-energy, all-day, elevated dining restaurant cluster,” Banks said. “We are trying to provide a little bit of what we think Alpharetta as a city is missing.” Food courts, of course, have been mainstays in American malls for decades. But the food hall generally excludes fast-food chains and focuses on more elevated eats, mostly from local operators. “A curated food hall requires a lot of care and thought,” said Banks, who previously worked for Atlanta developer Paces Properties when it developed Krog Street Market. “Sometimes you have to say no to perfectly capable tenants who have money just because they don’t meet the vibe. It’s contradictory … But you can’t just cram a bunch of food and beverage operators in a box. -

21St Annual Restaurant Industry Conference

21ST ANNUAL RESTAURANT INDUSTRY CONFERENCE WEDNESDAY, MAY 3, 2017, COVEL COMMONS, UCLA WELCOME UCLA Extension is proud to present the 22nd Annual Restaurant Industry Conference, with this year’s focus on Dining Disrupted! The “digital tsunami” is powerful and unrelenting, posing life-changing challenges, opportunities, and seeming to require immediate responsiveness. It’s no secret that many established restaurants and suppliers are not only facing economic volatility but are continuously challenged by more informed and demanding diners. This year we honor Robert Brozin, who built Nando’s Roger Torneden from one restaurant to a truly world-wide brand serving millions of diners. As chief executive of Nando’s until Associate Dean, Executive Director of UCLA Online 2010, he used sheer creativity (and Portuguese- Director, Department of Business, Management style peri-peri sauce) to take a little restaurant from & Legal Programs, UCLA Extension Rosettenville, South Africa, to the world. Today, Nando’s is loved in America, Australia, the United Kingdom, and 20 other countries as diverse as Fiji and Bangladesh. UCLA Extension serves approximately 40,000 students annually through Westwood, Downtown Los Angeles, and Woodland Hills campuses, plus a substantial selection of online courses. Our students typically already have degrees and years of experience but are seeking enhanced or new careers. Our instructors are “best in class” practitioners approved by UCLA’s campus schools for academic and teaching qualifications. In the Business, Management & Legal Programs Department, we focus on certificate programs and courses across industries (e.g., web analytics and social media marketing, small business management, credit analysis, finance, accounting, etc.) and on specific industries (hospitality, financial services, consulting, security, real estate, etc.). -

Pentagon Salutes Revised Food Courts Options Range from Quick Bites to Sit-Down Dining by BARRY LOBERFELD ASSISTANT EDITOR

FACILITY PROFILE Pentagon Salutes Revised Food Courts Options Range From Quick Bites to Sit-Down Dining BY BARRY LOBERFELD ASSISTANT EDITOR aving completed the last in a seven-year three-stage renova- tion of Pentagon foodservice, the iconic Department of Defense H(DoD) building’s cuisine spans the spectrum from fast food to fi ne dining. Three main food courts comprise the lion’s share of Pentagon food service. Two of the food courts, each offering seating for approximately 250, feature a mélange of branded and non-branded concepts, includ- ing Peruvian Chicken, Taco Bell, McDonald’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Sbarro and Panda Express, plus clerk-served salad bars and fresh sandwich and Panini stations. The largest food court, the Concourse Food Court, is also the one opened most recently, in September. It is an 875-seat space that houses a Burger King, Subway, Popeyes, Starbucks, RollerZ, Surf City Squeeze and a Dunkin’ Donuts/Baskin-Robbins joint concept. Single-unit food service operations, which are spaces featuring and run by only one business, include a 180-seat Sbarro; the Center Court Café, a 70-seat café located in the middle of the Pentagon’s Center Courtyard; a 40-seat Subway; a 24/7 Dominic’s food service operation; and various cart operations. On Dec. 2, 2009, foodservice renovation plans culminated with the new Pentagon Dining Room opening its doors, introducing a fi ne-dining experience and signaling the work had reached completion. “This facil- ity,” said Jeff Keppler, busi- ness manager/contracting offi cer for the Department of Defense Concessions Committee (DoDCC), “is a 220-seat tablecloth res- taurant that also offers two private function rooms, capable of seating 40 and another with a capacity of 20. -

SG -Menu Flyer (Ver 2) 2020 2

MOST POPULAR PROTEIN & ENERGY FRESH JUICE BAR ADD ONS OUR SINGAPOREAN FAVES! STAY TONED & TERRIFIC FRESHLY SQUEEZED JUICE, NO ADDED SUGAR HEALTHY BOOSTERS add an extra kick to your drink Hi, and welcome to Boost! All Berry Bang Watermelon Lychee Crush Protein Supreme Premium Brekkie To Go-Go 5 A Day Juice Immunity Juice Energiser Booster ^ Green Tea Booster Life can sometimes be a whirlwind, and trying to remember to get all the strawberries, raspberries, freshly juiced watermelon, banana, toasted muesli, dates, banana, toasted muesli, honey, freshly squeezed orange, freshly freshly juiced watermelon, freshly refresh and energise with green tea extract fruits and vegetables we need each day is the last thing on our busy minds. blueberries, apple juice, lychees, sorbet & ice whey protein, chia seeds, cinnamon, low fat milk or soy, juiced apple, carrot, celery, squeezed orange, strawberries & ice guarana extract, ginseng extract, This is where Boost comes to the nutritional rescue – we make healthy easy! honey, coconut water, coconut milk & ice TD4 vanilla yoghurt & ice beetroot & ice + immunity booster taurine and vitamin E Vita Booster At Boost, our brand is empowered by the good stuff. Every single smoothie Mango Magic Berry Crush + immunity booster + energiser booster + vita booster at least 10% of your RDI of essential and juice is bursting with real fruit and/or veggies. We know that everyone mango, banana, mango nectar, raspberries, strawberries, + vita booster vitamins and minerals (vitamin A, B12, is different. That’s why there’s a Boost juice or smoothie to suit every body blueberries, apple juice, sorbet & ice 31g of protein Wild Berry Juice Vita C Detox Juice Wheatgrass Powder C, D, E, niacin, riboflavin, pyridoxine, and every taste. -

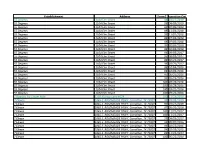

Establishment Address Score2inspection Date

Establishment Address Score2Inspection Date 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 10/17/2019 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 04/09/2019 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 04/09/2019 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 11/01/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 11/01/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 07/03/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 07/03/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 02/08/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 02/08/2018 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 96 08/03/2017 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 96 08/03/2017 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 96 02/21/2017 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 96 02/21/2017 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 10/04/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 98 10/04/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 95 05/25/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 95 05/25/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 100 03/28/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 100 03/28/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 100 03/22/2016 55 Degrees 1104 Elm Street 100 03/22/2016 7 Degrees Ice Cream Rolls 2150 N Josey Lane #124 100 11/18/2019 7-Eleven 1865 E. ROSEMEADE PKWY, Carrollton, TX 75007 98 09/03/2019 7 Eleven 1865 E. ROSEMEADE PKWY, Carrollton, TX 75007 90 01/14/2019 7 Eleven 1865 E. ROSEMEADE PKWY, Carrollton, TX 75007 97 05/31/2018 7 Eleven 1865 E. ROSEMEADE PKWY, Carrollton, TX 75007 100 11/21/2017 7 Eleven 1865 E. -

Building a Trusted and Connected Customer Experience in China

Customer first Building a trusted and connected customer experience in China KPMG China Customer Experience Excellence report kpmg.com/cn ¥ ¥ ¥ Foreword In our first KPMG China Customer Experience Excellence report, we look in detail at the state of customer experience in China to understand what market leaders are doing to drive success. Many of our clients prioritise customer centricity While technology has played a pivotal role in and are continuously looking to improve customer reducing time and effort, and improving convenience experience. In order to accomplish this, organisations for customers, creating a personalised offering, need to have an up-to-date understanding of their engendering trust and delivering a brand promise customers and readily adjust their operations to that resonates with customers are also shown to be meet customers‘ needs. immensely important. The KPMG China Customer Experience Excellence Looking ahead, the Greater Bay Area (GBA) initiative report focuses on mainland China and Hong Kong will be the next force of change for customers customers to find out what they value most when in mainland China and Hong Kong. Improved interacting with brands, and understand what infrastructure and transport connectivity means that other factors are important for organisations to companies which optimise their customer strategy successfully deliver a market-leading customer accordingly will be better positioned to maximise the experience. To explore the topic, KPMG China took new business opportunities available. part in a survey of over 5,000 customers, who were asked questions about more than 200 brands across We hope our insights provide you with a more mainland China and Hong Kong. -

A Literary Journey to Rome

A Literary Journey to Rome A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Christina Höfferer All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7328-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7328-4 CONTENTS When the Signora Bachmann Came: A Roman Reportage ......................... 1 Street Art Feminism: Alice Pasquini Spray Paints the Walls of Rome ....... 7 Eataly: The Temple of Slow-food Close to the Pyramide ......................... 11 24 Hours at Ponte Milvio: The Lovers’ Bridge ......................................... 15 The English in Rome: The Keats-Shelley House at the Spanish Steps ...... 21 An Espresso with the Senator: High-level Politics at Caffè Sant'Eustachio ........................................................................................... 25 Ferragosto: When the Romans Leave Rome ............................................. 29 Myths and Legends, Truth and Fiction: How Secret is the Vatican Archive? ...................................................................................................