Evaluation of Unhrc Candidates for 2020-2022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conheça Os Convidados Da Flink Sampa E Do Troféu Raça Negra

CONHEÇA OS CONVIDADOS DA FLINK SAMPA E DO TROFÉU RAÇA NEGRA A Flink Sampa e o 12º Troféu Raça Negra vai reunir entre os dias 22 a 24 de novembro um grupo relevante de escritores, atores, diretores de teatro, bailarinos e personalidades do mundo político e intelectual. Conheça os perfis de alguns deles: Graça Machel (África do Sul) - Ativista política e defensora dos Direitos Humanos, tornou-se a primeira mulher a ser primeira dama de duas nações. Em 1976, casou com o presidente de Moçambique, Samora Machel. Em 1998, tornou-se a terceira mulher do primeiro presidente negro da África do Sul, Nelson Mandela. Nascida em Moçambique, ganhou uma bolsa de estudos, tendo se formado em Filologia da Língua Alemã pela Universidade de Lisboa. De volta ao seu país natal, ingressou na Frelimo, durante a Luta Armada de Libertação Nacional. Aos 29 anos, foi nomeada ministra da Educação e Cultura do primeiro governo moçambicano. Após a morte de Samora Machel, criou a Fundação para o Desenvolvimento da Comunidade,que preside até hoje. Nos anos 90, realizou a pedido da ONU um estudo sobre o impacto dos conflitos armados na infância, que ficou conhecido como “Relatório Machel”, que lhe rendeu a medalha Nansen, das Nações Unidas em 1995. Três anos depois, casou-se com Nelson Mandela. Em 2010 foi eleita pela revista Times uma das 100 figuras mais influentes do mundo. Isabel Ferreira (Angola) - Formada em Direito, Teatro e Cinema, a escritora angolana Isabela Ferreira esteve sempre ligada às artes. Ainda jovem, participou das Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola, onde fez parte de um grupo musical. -

Israel at the UN: a History of Bias and Progress - September 2013

Israel at the UN: A History of Bias and Progress - September 2013 Introduction The United Nations (UN) has long been a source of mixed feelings for the Jewish community. While the UN played a pivotal role in the creation of the State of Israel, the international body has a continuing history of a one-sided, hostile approach to Israel. After decades of bias and marginalization, recent years have brought some positive developments for Israel to the UN. Nonetheless, the UN‟s record and culture continue to demonstrate a predisposition against Israel. Israel is prevented from fully participating in the international body. Indeed, in a meeting in April 2007, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon acknowledged to ADL leaders that Israel has been treated poorly at the UN and that, while some progress has been made, this bias still remains an issue. Secretary Ban stated this view publicly during his visit to Israel in August 2013. Considering the international body‟s pivotal role in the establishment of the Jewish State, there is a certain paradox that the UN is often a forum for the delegitimization of the State of Israel. In fact, the UN laid the essential groundwork for the establishment of Israel by passing UN Resolution 181 in 1947, which called for the partition of British Mandate Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. Following Israel's independence in 1948, the Jewish State became an official member-state of the international body. Since Israel‟s establishment, Arab member states of the UN have used the General Assembly (GA) as a forum for isolating and chastising Israel. -

Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures

Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures Divorce and Custody: Contemporary Practices: Mauritania and Egypt (5,360 words) Article Table of Contents 1. Moorish Women’s Agency 2. Khulʿ Versus Repudiation in Islamic Jurisprudence 3. Divorce and Bridewealth 4. Khulʿ in Egypt 5. The Status of Divorced Women in Egypt and in Mauritania 6. Bibliography Moorish Women’s Agency Moorish women in Mauritania did not wait for the introduction of a personal status code that guaranteed their right to divorce. The situation of Moorish women in this regard is different from that of Moroccan or Egyptian women who rediscovered this right through the legislative reforms concerning personal status. Thus, in Morocco the reform of the family code of 2004, the “New Mudawanna,” permits a woman to add a clause to her marriage contract giving her the right to divorce if her husband takes another wife. In Egypt, the personal status code of 2000 gives women the right to divorce, or khulʿ, even without the consent of her husband. It may also be noted that in Egypt and Morocco, legislative advances most often concern only urban zones and certain social milieus, and are not always implemented, given the weight of tradition and the persistence of certain types of gender relations. By contrast, Moorish women know how to exploit the social importance of their right to divorce, and are well supported by their families. Almoravids introduced the Mālikī school of jurisprudence into this region in the eleventh century. Moorish society is made up of Bedouin tribes, many of which are now sedentary and concentrated mainly in the capital city of Nouakchott. -

Mark Your Calendar! Development Goals (Mdgs)

Arab African Advisers Restructure your future Governance Observer Monthly newsletter that brings in best practice on governance with a focus on Arab and African countries experiences Vol. 1, Issue 10, March 2014 In this issue Gender Equality Gender equality and women‟s empowerment are human rights that are Page 1 - Gender Equality critical to sustainable development and achieving the Millennium - Mark Your Calendar! Development Goals (MDGs). Despite progress in recent years, women and girls account for six out of 10 of the world‟s poorest and two thirds of the Page 2 - Legislative Updates world‟s illiterate people. Only 19 percent of the world‟s parliamentarians are - Facts & Figures women and one third of all women are subjected to violence whether in times of armed conflict or behind closed doors at home. This is why UNDP Page 3 - Rwanda: A Revolution in integrates gender equality and women‟s empowerment into its four focus Rights for Women areas: poverty reduction, democratic governance, crisis prevention and - Women Empowerment: recovery, and environment and sustainable development… Union for the Mediterranean Conference When women and men have equal opportunities and rights, economic Held to Determine Priority growth accelerates and poverty rates drop more rapidly for everyone. Projects Reducing inequalities between women and men is critical to cutting in half Page 4 - Regulatory Policy and the number of people living in absolute poverty by 2015... Behavioural Economics The world‟s poorest and most vulnerable people are dependent -

Unemployment

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CONTENTS Acknowledgements . .. ix Abbreviations & Acronyms . xi Executive Summary . xiii Growth and Jobs: Low Productivity, High Demand for Targeted Skills . xiii Youth-related Constraints: Women, Mobility, and Core Competencies . xv Labor Market Programs: A Better Balance between Demand and Supply . xvi Transforming the Youth Employment Trajectory: Toward an Integrated Approach .. xvii Context and Objectives . 1 Conceptual Framework . 2 Approach . 4 Profile of Jobs and Labor Demand . 7 Growth Trends . 7 Types and Quality of Jobs . 9 Labor Costs . 12 Demand for Workforce Skills . 14 Recruitment and Retention . 14 Conclusions . 16 Profile of Youth in the Labor Force . 17 Demographic and Labor Force Trends . 17 Education . 20 Gender . 21 Unemployment . 23 Job Skills and Preferences . 24 Conclusions . 28 MAURITANIA | TRANSFORMING THE JOBS TRAJECTORY FOR VULNERABLE YOUTH iii Landscape of Youth Employment Programs . 29 Mapping Key Labor Market Actors . 29 Youth Employment Expenditure . 30 Active Labor Market Programs . 33 Social Funds for Employment . 33 Vocational Training . 34 Monitoring and Evaluation of Jobs Interventions . 34 Social Protection Systems . 34 Labor Policy Dialogue . 36 Conclusions . 37 Policy Implications: Transforming the Youth Employment Trajectory . 39 Typology of Youth Employment Challenges and Constraints . 39 From Constraints to Opportunities . 40 Toward an Integrated Model for Youth Employment . 48 Conclusions: Equal Opportunity, Stronger Coalitions . 48 Technical Annex . 49 Chapter 1 . 49 Chapter 2. 52 Chapter 3 . 56 Figues, Tables, and Boxes FIGURE 1 Conceptual framework for jobs, economic transformation, and social cohesion . 3 FIGURE 2 Growth outlook for Mauritania, overall and by sector, 2013–2018 . 8 FIGURE 3 Sectoral contribution to GDP and productivity, Mauritania, 1995–2014 . -

Advance Unedited Version Distr.: General 3 June 2013

A/HRC/23/21 Advance Unedited Version Distr.: General 3 June 2013 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-third session Agenda item 7 Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Richard Falk* Summary In the present report, while noting the continuing non-cooperation of Israel, the Special Rapporteur addresses Israel‟s Operation “Pillar of Defense” and the general human rights situation in the Gaza Strip, as well as the expansion of Israeli settlements – and businesses that profit from Israeli settlements and the situation of Palestinians detained by Israel. * Late submission. GE.13- A/HRC/23/21 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–7 3 II. The Gaza Strip ......................................................................................................... 8–30 5 A. Operation “Pillar of Defense” ......................................................................... 8–15 5 B. Economic and social conditions...................................................................... 16–19 9 C. Health in Gaza ................................................................................................ 20–22 10 D. Ceasefire implementation ............................................................................... 23–30 11 III. Palestinian detainees in Israeli prisons and detention -

Knowledge Management for Culture and Development: MDG-F Joint

AARABRAB STATESSTATES AFRICA LATIN AMERICA South East EUROPE ASIA ARAB STATES CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT CULTURE CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT CULTURE AND DEVELOPM DEVELOPMENTCULTURE CULTURE AND DEVELOPMEN CULTURE AND DEVELO CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT MOROCCO MOROCCO MDG-F JointProgrammes PALESTINIAN TERRITORY PALESTINIAN in EGYPT, MAURITANIA, EGYPT, and the OCCUPIED OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY MOROCCO EGYPT MAURITANIA Culture and Development in the Arab States Sharing centuries-old vast cultural, religious, linguistic and historical heritage, the Arab States have long placed their heritage at centre stage, focusing on its pro- motion for tourism as a path to development. The recent Arab Spring movement has indicated a wave of change that has swept the Arab region, where people are calling for new solutions that will bring peace and development. In this ground-breaking transition taking place in the Arab region, culture is a powerful source of hope and identity, a motor of social and economic development, playing a key role in reconstruction and in laying the groundwork for a culture of peace. Within this context, the MDG-F Culture and Development Joint Programmes The MDG-F Joint Programmes on Culture implemented in the Arab States greatly contribute to a holistic vision of development and Development in the Arab States in which the role of culture is highly valued. Focusing particularly on safeguarding > 4 Joint Programmes: Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco and occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) the diverse cultural heritage and using it as an enabler -

Compromiso Contra El Antisemitismo Y Por La Diversidad

COMPROMISO CONTRA EL ANTISEMITISMO Y POR LA DIVERSIDAD ¿QUÉ BUSCA TRUMP EN MEDIO ORIENTE? POSVERDAD Y ANTISEMITISMO INVITADA POR LA DAIA AL PAÍS PILAR | AÑO 11 NÚMERO 69 RAHOLA EN LA ARGENTINA | 2018 - ABRIL ENERO Sumario > 6 Editorial Año 11 • Número 69 > 8 Nota de tapa: Pilar Rahola en la Argentina Enero - Abril 2018 > 22 ¿Quién es Mario Pérez? Publicación de la Delegación de > 28 Acto central del Día del Holocausto Asociaciones Israelitas Argentinas > 40 Posverdad y antisemitismo | Por David Schabelman (DAIA) de distribución gratuita Tel.: 4378-3200 > 44 Proyecto Raíces [email protected] www.daia.org.ar > 56 ¿Qué busca Trump en Medio Oriente? > 60 Presentación Exclusión-Inclusión 4 Staff > 68 La ruta norte del Holocausto judío | Por Profesor Editor responsable Victor Zajdenberg Dr. Alberto Indij > 74 Proyecto Juicio en Ausencia Director Editorial y Periodístico > 82 Entrevista a Claudio Presman Víctor Garelik > 86 Desayunos del CES con colectivos Directora de Contenidos > 88 Jerusalem ciudad de paz | Por Jaime Jacubovich Académicos Marisa Braylan > 90 Juicio a neonazis en Mar del Plata Coordinador Editorial > 96 30º aniversario: los judíos soviéticos y la realización Leandro Peres Lerea de la historia | Por David Harris > 100 Las bellas y las bestias | Traducción: Publicidad Fundación Amigos de DAIA Julián Schvindlerman 4378-3200 > 102 Entrevista a Enrique Molteni | Por Julián Schvindlerman Fotografía > 106 La visión sionista de Teodoro Hertzl | Por Julián Leonardo Kremenchuzky Schvindlerman Diseño y edición > 110 Entrevista a Gustavo Posse | Por Norma Luján Ari Glancszpigiel para > 112 “Bibi” y el poder: ¿Un romance eterno? | Por Damián Szvalb www.ag-estudio.com.ar > 118 Antisemitismo en Suecia | Por Shimón Samuels Impresión > 122 T20 en Argentina | Por Dra. -

Nnar Eiilorailtil

Frcn 8. T.t - 90 v n Sierra, Mcb. 30. - s.r.r , 7 rrMatioa, Mcb. 31. Froa TftiteosTcrt .Ml 1 . Mikara, Apr. 22. For TuteoiTcri Niagara, Apr. 21. 5 Evening BulleUn. Est. 1882, Na 581S. 22 PAGES. HOKOLULU, TERRITORY OF HAWAII, SATURDAY, MAIICII 2S, 1914. 22 PAGES. PRICtt FIVE CE2iT3 Hawaiian Star. VoL XXI. No. 855. 11 nnar m T7' flF;R!'"f',, John V. Francis, CAP. PENHALLOW Governor of Texas ( 'I. Civil Yar Veteran, Yould Send Rangers Answers Last Call DIES AS RESULT Across Rio Grande --7 J OF BROKEN HIP - - Lsktil UUuy iicnei t mmmi m, ay $ Well-kno- wn Prom- Con- Promice Hade That Souza of Kohala Willi be Master and i Rebel General Telegraphs That Fighting Dismissed is Believed by Pacheco to'be Error inent Mason Suffered Acci-- tinues to be Heavy and That He Exp2ct3 to dent on March 9 V Inspired by His Opponent for the Post-- ; Occupy Torreon Sometime Tonight mastership of Honolulu Resigna- - REMAINS COMING HERE 240 Creusot Cannon and 10,000,000 ; IN THE S. S. MANOA March 1 2 ! Rounds Ammunition Purchased tion Took Effect ! Htnr-BuUft- ! ' ln Cable . - (Special VVas in Best: of Health Up to I . AMOoiated Irs3 Catll 2S-IroiI- sIonal arp WASHINGTON, D. March 28. M. C. Pacheco is out -- .PARIS France, March lrcsUrnt Haerta's arrnU ; C, of Suffering - Fall , Time busily engaged in this city porrhaslng a run and amnianltloo. That fur of the running in the fight for the postmastership of Honolu- : 10,(;CO,()00 ammunition been pur on. Inspection Tour , 210 lYeasot cannon and ronnd.4 of hate chased for delhery next week. -

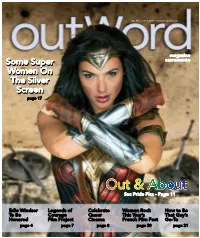

578 • June 8, 2017 • Outwordmagazine.Com

No. 578 • June 8, 2017 • outwordmagazine.com magazine SomeSome SuperSuper sacramento WomenWomen OnOn TheThe SilverSilver ScreenScreen page 17 Out & About Sac Pride Pics - Page 11 Edie Windsor Legends of Celebrate Women Rock How to Be To Be Courage Queer This Year’s That Guy’s Honored Film Project Cinema French Film Fest Go-To page 4 page 7 page 8 page 20 page 21 COLOR COLOR Convention Center Renovation Gets OK Years of Progress to End AIDS he Sacramento City Now Threatened commentary by MSMGF Council on at their ital programming for gay, bisexual and other men who have TTuesday, May 30th sex with men around the world will be slashed if the President’s meeting approved the go-ahead Vproposed budget released earlier this week is approved. for project design to start Over $1 billion in arbitrary cuts to global Vaccine Initiative (IAVI); HIV programs at the State Department and $2.4 billion from the development drawing plans for a larger, USAID in the President’s budget would assistance and economic support fund more attractive and competitive mean increases in avoidable HIV accounts, which would hamper the U.S’.s Convention Center. transmission and more unnecessary deaths. ability to support critical LGBTI rights The White House’s budget calls for an programs abroad; and No major physical improvements have approximate 17 percent cut to components of Voluntary contributions to UN agencies been made to the Convention Center in the the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS – such as UNDP and UNAIDS – which last two decades. Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to would seriously threaten progress and The project expands building capacity, Fight AIDS, commitments within those makes the building easier to navigate, Tuberculosis and agencies to gay men and other expands the use of flexible space, upgrades Malaria, a key populations, as articulated the interior and technology and includes complete by the Global Platform to Fast indoor/outdoor meeting and function defunding of HIV Track the HIV and Human areas. -

P40 Layout 1

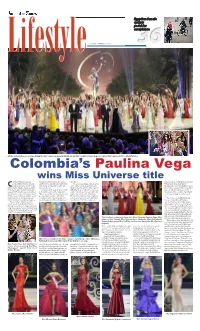

Egyptian female cyclists pedal for acceptance TUESDAY, JANUARY 27, 2015 36 All the contestants pose on stage during the Miss Universe pageant in Miami. (Inset) Miss Colombia Paulina Vega is crowned Miss Universe 2014.— AP/AFP photos Colombia’s Paulina Vega wins Miss Universe title olombia’s Paulina Vega was Venezuelan Gabriela Isler. She edged the map. Cuban soap opera star William Levy and crowned Miss Universe Sunday, out first runner-up, Nia Sanchez from the “We are persevering people, despite Philippine boxing great Manny Cbeating out contenders from the United States, hugging her as the win all the obstacles, we keep fighting for Pacquiao. The event is actually the 2014 United States, Ukraine, Jamaica and The was announced. what we want to achieve. After years of Miss Universe pageant. The competition Netherlands at the world’s top beauty London-born Vega dedicated her title difficulty, we are leading in several areas was scheduled to take place between pageant in Florida. The 22-year-old mod- to Colombia and to all her supporters. on the world stage,” she said earlier dur- the Golden Globes and the Super Bowl el and business student triumphed over “We are proud, this is a triumph, not only ing the question round. Colombian to try to get a bigger television audi- 87 other women from around the world, personal, but for all those 47 million President Juan Manuel Santos applaud- ence. and is only the second beauty queen Colombians who were dreaming with ed her, praising the brown-haired beau- The contest, owned by billionaire from Colombia to take home the prize. -

UN Human Rights Experts

ISSUE BRIEF No. 3942 | MAY 16, 2013 U.N. Human Rights Experts: More Transparency and Accountability Required Brett D. Schaefer and Steven Groves ecent statements by United Nations Human issues or situations in specific countries. In the RRights Council Special Rapporteur Richard course of their duties, the mandate holders (entitled Falk rekindled a debate over how such experts “special rapporteurs” or independent experts) may should be held accountable when their behavior vio- visit countries, bring attention to alleged human lates the conduct expected of them. Moreover, the rights violations or abuses through statements and scrutiny elicited by Falk’s statements has exposed communications, conduct studies, and otherwise the fact that funding for special procedures deserves comment, advocate, and raise awareness of their more transparency, especially regarding the ability mandates. As of April 1, 2013, there were 36 the- of mandate holders to not disclose financial support matic mandates and 13 country-specific mandates received from sources other than the U.N. regular of which a number were inherited by the HRC from budget. its predecessor, the discredited U.N. Commission on The U.S. should address these issues by demand- Human Rights.1 ing that the Human Rights Council (HRC) adopt Many mandate holders conduct themselves pro- an explicit procedure for dismissing mandate hold- fessionally and strive to fulfill their responsibilities ers who grossly or repeatedly violate the Code of with independence, impartiality, personal integri- Conduct for Mandate Holders, directing the HRC to ty, and objectivity, which, along with expertise and publicly post the financial implications of the spe- experience, are identified by the HRC as being of cial procedures, and requiring full disclosure of all “paramount importance” in the selection of mandate financial and other support received by mandate holders.2 Although Falk, the “Special Rapporteur on holders.