“Biking” School? How Some Schools Have Pulled Ahead in Cycling Rates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Changes to Cycle Infrastructure to Improve the Experience of Cycling for Families

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository Exploring changes to cycle infrastructure to improve the experience of cycling for families Dr William Clayton1 Dr Charles Musselwhite Centre for transport and Society Centre for Innovative Ageing Faculty of Environment and Technology School of Human and Health Sciences University of the West of England Swansea University Bristol, UK Swansea, UK BS16 1QY SA2 8PP Tel: +44 (0)1792 518696 Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 82316 Web: www.drcharliemuss.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @charliemuss Website: www.uwe.ac.uk/et/research/cts Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: Cycling, infrastructure, motivation, families, behaviour change. Abstract: Positive changes to the immediate cycling environment can improve the cycling experience through increasing levels of safety, but little is known about how the intrinsic benefits of cycling might be enhanced beyond this. This paper presents research which has studied the potential benefits of changing the infrastructure within a cycle network – here the National Cycle Network (NCN) in the United Kingdom (UK) – to enhance the intrinsic rewards of cycling. The rationale in this approach is that this could be a motivating factor in encouraging greater use of the cycle network, and consequently help in promoting cycling and active travel more generally amongst family groups. The project involved in-depth research with 64 participants, which included family interviews, self-documented family cycle rides, and school focus groups. The findings suggest that improvements to the cycling environment can help maintain ongoing motivation for experienced cycling families by enhancing novel aspects of a routine journey, creating enjoyable activities and facilitating other incidental experiences along the course of a route, and improving the kinaesthetic experience of cycling. -

Highway 17 and 69 Controlled Access Highway Response

Sudbury Cyclists Union March 28, 2014 Re: Route Planning Study, Highway 17 from Sudbury to Markstay and Highway 69 from the Estaire Road Interchange to Highway 17 The Sudbury Cyclists Union (SCU) has serious concerns about how the implementation of controlled access highways have affected cyclists in the Sudbury region. We also have some specific concerns about the implementation of this project as it relates to the safety of cyclists. The intent of all provincial roadwork is to improve the safety of its users. Traditionally, the focus has been on the safety of motorized traffic. The safety of pedestrians and cyclists has been long neglected on our highways. On page 2.1 of your “Study Design Report”, you note that to “promote a multimodal transportation network” is a key provincial responsibility” as is to “be a leader in road safety”. The sole intent of implementing controlled access highways is to facilitate the safe movement of motorized traffic. While implementing such highways draws dangerous traffic away from more local routes that are used by cyclists, alternative safe and convenient routes for cyclists are often an afterthought and are not an integral part of the planning process. An example is the Highway 69 corridor leading south from the City of Greater Sudbury that has been built without guaranteeing an alternative right of way for cyclists wishing to travel south. This controlled access highway has closed off access for non-motorized users to several towns and tourist areas, including the town of Killarney and the iconic Killarney Provincial Park. In other provinces, in particular in Western Canada, major motor routes similar to our controlled highways have paved shoulders that are used by cyclists. -

Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: an Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah Stephanie A. Tomlin Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Stephanie A., "Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7195. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLANNING FOR ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION IN THE WESTERN UNITED STATES: AN ALTERNATIVE FUTURE FOR CACHE VALLEY, UTAH by Stephanie A. Tomlin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Bioregional Planning Approved: Bartlett Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. Richard Toth, M.L.A. Major Professor Committee Member Jordy Guth, M.S. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Stephanie A. Tomlin, 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah by Stephanie A. Tomlin, Master of Bioregional Planning Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Bartlett (Barty) Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. -

A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure

Build it: A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure A thesis submitted by Ian Thistle In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Tufts University February 2016 Adviser: Mary Davis Reader: Barbara Parmenter Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................... iv List of Tables ........................................................................................ v Abstract .................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ................................................................................. vii Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review.................................................................... 4 Benefits of Cycling ................................................................................ 4 How can cities influence mode choice towards biking? ......................... 6 Evaluating Road Infrastructure for Cycling ............................................ 9 Analysis of Street Networks: “Build it! But Where?” ............................ 13 Chapter 3: Methods ............................................................................... 17 Step 1: Selecting the comparison methodologies ............................... 19 Step 2: Selecting the sample ............................................................. -

Smart Choices for Cities: Cycling in the City

Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Pictures © Shutterstock, 2016, pages: 1, 14, 15, 20, 22. 2 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Table of contents Preface. 4 Introduction . 5 The city is changing . 5 Why cycling? . 8 An integrated approach to cycling provision in the urban environment. 9 Infrastructure.and.equipment. 10 Introduction. 10 Cycling safety . 10 Where do most accidents happen? . 11 Senior cyclists and safety . 12 Equipment . 12 Implications for infrastructure . 12 Building blocks for safe infrastructure . 14 Recognisability . 16 Specific infrastructural situations . 16 Multi-modal Transport. 16 Bicycle Congestion . 18 Bicycle Theft . 18 Supporting.Actions. 19 Introduction. 19 Building an organization in (local) government . 19 Working with stakeholders . 20 Cycling Association . 20 Employers: Bicycle to work . 20 Cycle Marketing . 20 Education . 21 Insights in cycling behaviour . 21 Gathering data . 21 Cycling in traffic models . 21 From.ideas.to.policy:.Recommendations.for.approaching.investments.in.cycling . 22 Bibliography. 24 Notes. 26 3 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Preface Thank you for reading the eighth and final policy analysis of Over 70% of all Europeans live in cities and cities are the CIVITAS WIKI Policy Analysis Series. becoming increasingly congested. Citizens suffer from poor air quality and noise, which makes the cities less liveable. The mission of the CIVITAS WIKI project was to provide This document provides information about measures that can information on clean urban transport and the CIVITAS be taken in order to increase the use of cycling as a transport Initiative to EU city planners, decision-makers and citizens. -

FLOW Portfolio of Measures: the Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing

THE ROLE OF WALKING AND CYCLING IN REDUCING CONGESTION A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES FLOW DOCUMENT TITLE The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures AUTHORS Thorsten Koska, Frederic Rudolph (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH); Case Studies: Benjamin Schreck, Andreas Vesper (Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen), Tamás Halmos (Budapesti Közlekedési Központ), Tamás Mátrai (Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem), Alicja Pawłowska (Municipality of Gdynia), Jacek Oskarbski (Politechnika Gdanska), Benedicte Swennen (European Cyclists’ Federation), Nora Szabo (PTV AG), Graham Cavanagh (Rupprecht Consult GmbH), Florence Lepoudre (Traject), Katie Millard (Transport Research Laboratory), Martin Wedderburn (Walk21), Miriam Müller, David Knor (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH) CONTACT Project coordinator: Rupprecht Consult Bernard Gyergyay: [email protected] Kristin Tovaas: [email protected] Project dissemination manager: Polis Daniela Stoycheva: [email protected] CITATION FLOW Project (2016). The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures. Brussels. Available at http://www.h2020-flow.eu. IMAGE DISCLAIMER The images in this document are used as a form of visual citation to support and clarify statements made in the text. The authors have made great effort to provide credit for every image used. If, despite our efforts, we have not given sufficient credit to the author of any images used, please contact us directly at [email protected] LAYOUT PEAK Sourcing DATE July 2016 The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union. Neither the INEA nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. -

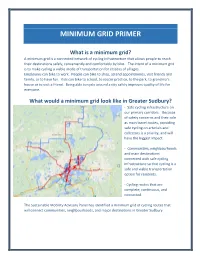

Minimum Grid Primer

MINIMUM GRID PRIMER What is a minimum grid? A minimum grid is a connected network of cycling infrastructure that allows people to reach their destinations safely, conveniently and comfortably by bike. The intent of a minimum grid is to make cycling a viable mode of transportation for citizens of all ages. Employees can bike to work. People can bike to shop, attend appointments, visit friends and family, or to have fun. Kids can bike to school, to soccer practice, to the park, to grandma’s house or to visit a friend. Being able to cycle around a city safely improves quality of life for everyone. What would a minimum grid look like in Greater Sudbury? - Safe cycling infrastructure on our primary corridors. Because of safety concerns and their role as main travel routes, providing safe cycling on arterials and collectors is a priority, and will have the biggest impact. - Communities, neighbourhoods and main destinations connected with safe cycling infrastructure so that cycling is a safe and viable transportation option for residents. - Cycling routes that are complete, continuous, and connected. The Sustainable Mobility Advisory Panel has identified a minimum grid of cycling routes that will connect communities, neighbourhoods, and major destinations in Greater Sudbury. Why is it important to have safe cycling on our busiest streets first? A transportation network relies on primary routes that secondary routes feed into and out of. This is true of any type of transportation, including cycling. The primary network needs to be constructed first, otherwise the transportation network is fragmented - the secondary routes do not connect to anything. -

Cycling Infrastructure Version 1

Cycling VERSION 1 infrastructure Cycling infrastructure In this chapter 01 Introduction 5 Kerbside activity 33 07 02 Choosing the right facility 6 General Design 35 08 2.1 Design parameters 6 8.1 Design controls 35 2.2 Types of cycle facility 8 8.2 Horizontal and vertical alignment 39 8.3 Widths and clearances 41 03 Approved facilities within the road reserve 11 8.4 Construction 45 3.1 Separated cycleway (busy, fast, or heavy traffic) 11 8.5 Drainage 46 3.2 Separated cycleway (low volume and slow traffic) 14 8.6 Signs and markings 47 3.3 Alternatives requiring specific approval 15 8.7 Lighting 48 3.4 Mixed traffic streets 16 3.5 Cycle streets 16 Ancillary features 49 09 3.6 Pedestrian priority areas (cycling and pedestrians) 17 3.7 Interim facilities 20 Design for maintenance 52 10 Appendix A 04 Other infrastructure 22 Cycle parking 53 4.1 Buffered cycle lanes 22 A.1 Introduction 53 4.2 Cycle lanes 23 A.2 Bicycle Parking General principles 54 4.3 Cycle lanes between other traffic lanes 23 A.3 Categories of bicycle parking 56 4.4 Shared paths 24 A.4 Types of bicycle parking 58 A.5 Types of bicycle stands 64 05 Off road cycle paths 25 A.6 Bicycle parking placement 67 A.7 Bicycle parking access 68 06 Intersections 26 A.8 Bicycle stand materials 68 6.1 Cycleway intersections 27 A.9 Signage and wayfinding for bicycle parking 68 6.2 Roundabouts 27 A.10 Bicycle parking demand 69 6.3 Signalised intersections 28 A.11 Bicycle parking at public transport terminals 70 6.4 Unsignalised intersections 30 A.12 Bicycle parking provisioning process 71 6.5 Midblock crossing 31 A.13 Building and installation 72 6.6 Vehicle crossings 32 A.14 Operation and maintenance 72 5794_20.04.21 2 TDM | ENGINEERING DESIGN CODE 3 Cycling infrastructure 01 Introduction PURPOSE Cycling infrastructure includes facilities that are dedicated for cycle use, as well as specific standards for general infrastructure to meet the needs of cycle users. -

LCDS Chapter 6 Signs and Markings

London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signs and markings | Contents 6. Signs and markings This chapter gives an overview of requirements on signing 6.2 Surface markings 06 to support cycling, both for dedicated infrastructure and 6.2.1 General requirements 06 for cyclists’ general use of the highway. 6.2.2 Lane markings 06 6.2.3 Give way markings 08 6.1 Signing requirements 01 6.2.4 Other markings for cycle tracks 09 6 .1.1 Signing principles 01 6.2.5 Cycle symbols and direction signing 10 6.1.2 Applying the principles 01 6.2.6 Coloured surfacing 13 6.1.3 Regulatory changes 02 6.1.4 Signs requiring enforcement 03 6.3 Signs 14 6.1.5 Signing to support wayfinding 04 6.3.1 Direction signs 14 6.3.2 Off-highway direction signs 16 6.3.3 Warning signs 16 6.3.4 Signs for pedestrian zones 17 6.3.5 Signs to minimise or avoid 18 6.3.6 Minimising sign clutter 18 6.3.7 Sign installation and mounting 21 6.4 Schedule of signs 23 Bibliography 29 Version control Version 1 (Dec 2014) – Published Q12 Version 2 (Sept 2016) – Amendments throughout following publication of TSRGD (2016) London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signing requirements 01 Signing plays an important role in supporting and Figure 6.1 Key signing considerations in CLoS 6.1 Signing requirements enforcing safer, more comfortable, legible and coherent cycling infrastructure. Road signs and Factor Indicator Relates in this markings are defined, together, as ‘traffic signs’ chapter to 6.1.1 Signing principles within the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. -

CITIES SAFER by DESIGN Guidance and Examples to Promote Traffic Safety Through Urban and Street Design VERSION 1.0

WORLD WRI ROSS CENTER FOR RESOURCES SUSTAINABLE INSTITUTE CITIES CITIES SAFER BY DESIGN Guidance and Examples to Promote Traffic Safety through Urban and Street Design VERSION 1.0 WRICITIES.ORG Cities Safer by Design i BEN WELLE QINGNAN LIU WEI LI CLAUDIA ADRIAZOLA- STEIL ROBIN KING CLAUDIO SARMIENTO MARTA OBELHEIRO This report was made possible through funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Design and layout by: Jen Lockard [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword 44 Pedestrian Crossings 46 Medians 3 Executive Summary 47 Median Refuge Islands 48 Signal Control 11 Traffic Safety for People 49 Lane Balance 12 Traffic Safety Across Selected World Cities 14 Nearly All Urban Dwellers are Affected by 53 Pedestrian Spaces and Access Traffic Safety in Cities to Public Space 15 Creating a Safer System for All People: 55 Basics of Safe Sidewalks Reducing Exposure and Risks 57 Shared Streets 18 Analyzing Traffic Safety in Cities 58 Pedestrian Streets and Zones 18 Performance Measures 59 Safe Places to Learn and Play 60 Open Streets 21 Key Urban Design Elements 61 Street Plazas 23 Block Size 24 Connectivity 65 Bicycle Infrastructure 25 Vehicle/Travel Lane Width 67 Bicycle Networks 26 Access to Destinations 68 Bike Lanes and Cycle Tracks 27 Population Density 70 Off-street Trails 71 Shared Bicycle Street 29 Traffic Calming Measures 72 Bicycle Safety at Intersections 31 Speed Humps 74 Bike Safety at Bus Stops 33 Speed Cushions 75 Bicycle Signals 34 Chicanes 35 Chokers 79 Safe Access to Transit Stations and Stops 36 Curb Extensions 82 Intersections with Bus Corridors 37 Raised Intersections/Crossings 83 Midblock Crossings 38 Traffic Circles 84 BRT/Busway Stations 39 Roundabouts 85 Terminals and Transfers 41 Arterial Corridors and Junctions 89 Conclusion 43 Arterials 92 References BICYCLE INFRASTRUCTURE Bicyclists require special attention in street design as they are one of the most vulnerable users in terms of traffic fatalities and injuries, yet an increase in safety and usage can lead to greater health and environmental benefits. -

Mobility Post-Pandemic: a Strategy for Healthier Cities August | 2020

KNOWLEDGE BRIEF MOBILITY POST-PANDEMIC: A STRATEGY FOR HEALTHIER CITIES AUGUST | 2020 INTRODUCTION The Covid-19 outbreak has had a major impact This pandemic has evidenced the vital role of public on our lives: the way we move, socialise and work. transport systems for accessing work and essential It has shown how vulnerable and unprepared our services, and the flexibility of city streetscapes to societies are to a pandemic crisis. It has also shown provide the necessary additional space for walking how strict decisions on individual mobility have and cycling. Despite its devastating impact, the significantly reduced air and noise pollution levels, crisis offers unique opportunities for cities to leading to the terrible environmental impacts from rethink and push for their mobility strategies to motorised transport becoming ever more apparent foster the use of sustainable transport modes and to the public. This has triggered a change in citizens’ provide safe and sustainable mobility options to mobility habits. citizens. In times such as these, adapted urban space management and new mobility services offer the possibility to support public transport systems, while providing additional space for active mobility, and contributing to reducing car use in cities. Each crisis offers opportunities to change, this crisis has set the basis on which decision makers and citizens should build upon and reposition economic and social recovery in projects fighting climate change for healthy cities. This Knowledge Brief will identify actions taken by cities to help maintain a good level of mobility access and to influence different demand and mobility behaviours, with the aim of better understanding the impact Covid-19 could have on cities’ mobility strategies. -

Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from Cities in the Portland, OR Region

Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from cities in the Portland, OR region FINAL DRAFT Lynn Weigand, Ph.D. Nathan McNeil, M.U.R.P. Jennifer Dill, Ph.D. June 2013 This report was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, through its Active Living Research program. Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from cities in the Portland, OR region Lynn Weigand, PhD, Portland State University Nathan McNeil, MURP, Portland State University* Jennifer Dill, PhD, Portland State University *corresponding author: [email protected] Portland State University Center for Urban Studies Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies & Planning PO Box 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 June 2013 All photos, unless otherwise noted, were taken by the report authors. The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their useful comments, which improved the document: Angie Cradock, ScD, MPE, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; and Kevin J. Krizek, PhD, University of Colorado Boulder. Any errors or omissions, however, are the responsibility of the authors. CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. i Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Bike Lanes................................................................................................................................ 7 Wayfinding Signs and Pavement Markings .................................................................