SOME UNUSUAL HAGGADAH PAGES 1924-1958 with a Number of Ritual Seder Objects Thrown In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haggadah: Why Is This Book Different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2Nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson

Haggadah: why is this book different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson Haggadah: Why is This Book Different? tells the story of how a Jewish text compiled in antiquity was adapted and reproduced over time and around the world. Featuring rare and scarce Haggadot (plural) from the Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, this exhibition shows the many ways in which the core Haggadah text, with its Passover rituals, blessings, prayers and Exodus narrative, was supplemented by songs, commentary and rich illuminations to reflect and respond to each unique period and circumstance in which the Jewish diaspora found itself. Outstanding and unusual examples are included, such as a sumptuous facsimile of the Barcelona Haggadah from the 14th century, a 1918 Haggadah from Odessa, Ukraine, the last Haggadah produced before Soviet censorship, and a Haggadah recently produced by the Jewish community of Jacksonville in remembrance of the Holocaust. This exhibition charts the development of a fascinating text over 600 years and encourages you to compare the ways in which older copies of the Haggadah were illuminated in contrast with more recent artistic interpretations. It invites you to observe how the Exodus story with its essential message about freedom is interpreted in light of contemporary events and to notice the many ways in which the text is adapted to suit the audience and preserve its relevance. What is this book? During the first two nights of Passover, a ceremonial dinner and ritual service, known as a Seder, is conducted in Jewish homes around the world. -

PDF Download Haggadah Ebook Free Download

HAGGADAH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jonathan Safran Foer | 160 pages | 22 Mar 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780241143605 | English, Hebrew | London, United Kingdom Haggadah PDF Book The Family Haggadah. In the first half of the century the Ashkenazi influence is apparent chiefly in the general overall design. Freimann, ; Ha- Pardes , ed. Passover Passover Pesach What you need to know about the festival of freedom. The more engaging to them personally you can make the haggadah, the more they will enjoy using it. The Haggadah includes various prayers, blessings, rituals, fables, songs and information for how the seder should be performed. Wiener, Bibliographie der Oster-Haggadah 2 , contains a list of editions between and ; idem, in: SBB , 7 , 90 — addenda of editions ; A. The social and economic growth of town life at this period fostered an increase in the number of secular workshops concerned with the manufacture of books. According to Jewish tradition, the Haggadah was compiled during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods, although the exact date is unknown. The Malbim theorized that the Haggadah was written by Judah ha-Nasi himself. This article was written in when anti-Semitism was widespread in the United States. Nearly all its folios are filled with miniatures depicting Passover rituals, Biblical and Midrashic episodes, and symbolic foods. Davidson, S. Printable Hebrew Haggadah. If the Jewish community is to be a home for all, we The Washington Haggadah illuminated in the Florentine style is one of his best. During the 13 th to 15 th centuries the Passover Haggadah was one of the most popular Hebrew illuminated manuscripts in Sephardi as well as Ashkenazi or Italian communities. -

The Sarajevo Haggadah Is One of the Oldest Manuscript Haggadahs in the World

JOSEPH IN THE SARAJEVO HAGGADAH Joseph Sold To Ishmaelites Joseph’s Brothers Bow To Him The Sarajevo Haggadah is one of the oldest manuscript Haggadahs in the world. It is believed to have been created in Northern Spain, around the year 1350. Carried out of Spain during the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, it changed hands many times over the next several centuries. In 1894, in Sarajevo, a child whose family was in difficult financial circumstances because his father had died brought the Haggadah to school to barter for tuition. The teacher recognized it as a manuscript of remarkable beauty and extraordinary historical value. Among the most impressive features of the Haggadah is a series of 69 illustrations depicting the stories of Genesis which serve as a prelude to the experience in Egypt and the Exodus. Fascinatingly, 17 of the illustrations focus on the story of Joseph, nearly a quarter of the pictures. Two of them appear above. Over the years, a number of scholars have been puzzled by this disproportionate emphasis on the story of Joseph. How would you explain it? Why would the Jews of Medieval Spain be so drawn to the story of Joseph? Could it be that they identified with him for some reason? These are questions you might consider discussing at your Seder. Pass the pictures around. What do you notice about the artwork? Does it provide any insight or answers to the questions? ITEMS TO CONSIDER IN ANSWERING THE QUESTIONS: Joseph was sold to Ishmaelites, the ancestors of the Arabs who ruled Spain for many years and under whom Jews rose to prominent positions; when the Sarajevo Haggadah was created, Christians had taken control of Spain; the clothing worn by Joseph and his brothers is typical of the period; Joseph was one of the first of our ancestors to become assimilated into a culture different from his own, in dress, language, marriage and even the names he gave his children. -

Modern Jewish History

Bookmarks of Jewish History The George Washington University Spring 2011 History 3001/Honors 2175 Prof. Daniel B. Schwartz W 2:00-4:30 PM Phillips 317 I. Edmund Kiev Library in Gelman (202) 994-2397 The Library of Congress Hebraica Section [email protected] Office Hours: F 12:30-2 “The study of Jewish history is an invitation to travel” Leon Wieseltier, Kaddish (1998) This course, which is being offered for the first time in Spring 2011, is an undergraduate seminar in the history of the Jewish book that also serves as an introduction to the remarkable riches of the Judaica collections of the Library of Congress and the Kiev Library in Gelman. In this course we will learn about the history of books in general and Jewish books in particular, studying how texts were made, circulated, and read. We will also learn about the ways in which books gave rise to new conceptions of knowledge and authority and even to new ideas of what it meant to be Jewish. And we will do all this on site at the Library of Congress and the Kiev Library, in the physical presence of the primary sources we are studying, many of them centuries old and exceedingly rare. The inaugural version of “Bookmarks” will be divided into two halves. In the first half of the semester, we will examine the impact of print on Jewish cultural development from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, a period often referred to as “early modern” in Jewish historiography, in part on account of the transformations wrought in Jewish life by the invention of movable type. -

Barcelona Haggadot

MUHBA LLIBRETS DE SALA, 22 BARCELONA HAGGADOT The Jewish Splendour of Catalan Gothic BARCELONA HAGGADOT The Jewish Splendour of Catalan Gothic Barcelona, the seat of a monarchy and a hub of Mediterranean trade, had an urban ethos that was receptive to the most innovative artistic in- fluences in the opening decades of the 14th cen- tury. At this juncture in the Gothic era, the city’s workshops constituted a highly active centre for the production of Haggadot, manuscripts that contain the ritual of the Passover meal, which were commissioned by families living in the Call (Jewish quarter) in Barcelona and in other Jewish communities. Jews and Christians alike worked on Haggadot and shared the same style and iconographic models. The Museu d’Història de Barcelona reunites in the exhibition Barcelona Haggadot, for the first time in more than six centuries, an extensive se- lection of these splendid works of the Catalan Gothic period that were dispersed around the world when the Jews were expelled. Barcelona Haggadah. The British Library, London, f. 28v Fringe areas where The Barcelona Call. Barcelona’s THE BARCELONA Jewish and Christian Jewish community lived in the properties neigh- western quarter of the city during boured each other the High Middle Ages. This area, JEWISH COMMUNITY IN or Call, as Jewish quarters were Roman-county Main Call known in Catalonia, was defined THE 14TH CENTURY wall in the late 11th century. In re- sponse to the rise in the number of inhabitants in the Call, King Jaume I authorised Jews to settle Second on land near the Castell Nou (new Call castle) outside the old defensive 1 Door walls. -

April 2019 Adar 2 - Nisan 5779 Passover 2019 Update Pre-Pesach Programs Services “Selling” Your Chametz Candle Lightings Siyum Hab’Khor Page 4

ADAT SHALOM SYNAGOGUE THE הקול ENDOWED IN MEMORY OF HARRY AND SH IRLEY NAC HMAN Vol. 76 No. 3 April 2019 Adar 2 - Nisan 5779 Passover 2019 Update Pre-Pesach Programs Services “Selling” Your Chametz Candle Lightings Siyum HaB’khor Page 4 SCHEDULE OF SERVICES The Sisterhood of Adat Shalom Mornings: Sundays. 8:30 A.M. Monday - Friday . 7:30 A.M. 77th Annual Shabbat . 9:00 A.M. Evenings (Minchah-Maariv): Donor Day Event Sunday - Friday . 6:00 P.M. Saturdays: Tuesday, May 7, 2019 April 6 . 8:00 P.M. April 13 . 8:00 P.M. April 20 . Minchah immediately following Unique Boutiques the Shabbat Pesach Kiddush April 27 . 8:15 P.M. Luncheon Program SHABBAT TORAH PORTIONS April 6 April 20 Woman of Distinction Tazria Pesach Shabbat HaChodesh Day 1 Honoree Beve ly Yost April 13 April 27 Metzora Pesach Shabbat Hagadol Day 8 Page 7 PEOPLE & PROGRAMS Meditation Mazal Tov to our AND MINDFULNESS April Bar Mitzvah with Rabbi Bergman April 13 Sundays, April 14 & 28 at 9:30 A.M. April 14 is Pre-Pesach Learning with Henry Jacob Nathan is the son Rabbi Bergman and Hazzan Gross of Alyse & Howard Nathan; the see page 4 grandson of Sheila z”l & Sidney z”l Find your internal spirituality Cohen, and Audrey z”l & Herbert and realize that Judaism z”l Nathan can make you happier. A refreshing hour for all ages. Sessions will continue throughout the year. There is no charge Shabbat Rocks Soulful Yoga This ser vice is a par ticipator y, with Rabbi Shere engaging and spirited ser vice and skilled yoga instructor for all ages, with instr umental Mindy Eisenberg accompaniment backing the beautiful Saturdays, April 6 & 13 at 10:00 A.M. -

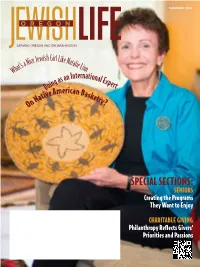

SPECIAL SECTIONS: SENIORS Creating the Programs They Want to Enjoy

NOVEMBER 2014 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON e Jewish Girl Like N a Nic atalie hat’s Linn W ern s an Int ational ng a Expe Doi rt American B tive aske Na try On ? SPECIAL SECTIONS: SENIORS Creating the Programs They Want to Enjoy CHARITABLE GIVING Philanthropy Reflects Givers’ Priorities and Passions Jewish Federation of Greater Portland invites you to THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 13 beginning at 5:30 pm Mittleman Jewish Community Center $36 before November 7, $45 after purchase tickets today at Three Surgeons, One Goal ThreeNow open Surgeons, in the Pearl One District Goal www.jewishportland.org/impact HelpingNow open patients in achieve the Pearlbeautiful District results Helping patients achieve beautiful results andHelping improved patients self-confidence. achieve beautiful 30 resultsyears or call Rachel at 503-892-7413 and improved self-confidence. 30 years ofand combined improved experience self-confidence. in a full 30suite years of combined experience in a full suite of services:combined experience in a full suite •of Cosmetic services: & reconstructive breast surgery •*of Cosmetic services: & reconstructive breast surgery • CosmeticCosmetic & & reconstructive reconstructive breast breast surgery surgery •* Cosmetic & reconstructive breast surgery * BodyCosmetic contouring & reconstructive & liposuction breast surgery •* BodyBody contouring contouring & & liposuction liposuction •* Body contouring & liposuction •* FacialBody contouringcosmetic surgery & liposuction & non-surgical •* FacialBody contouringcosmetic surgery & liposuction -

Spotlight 029 Phase Shift Judaism

Wordtrade.com| 1202 Raleigh Road 115| Chapel Hill NC 27517| USA ph 9195425719| fx 9198691643| www.wordtrade.com Spotlight 029 On the Question of the "Cessation of Prophecy" in Ancient Judaism by L. Stephen Cook [Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism, Mohr Siebeck, Phase Shift Judaism 9783161509209] Jews and Christians in the First and Second Table of Contents Centuries: The Interbellum 70–132 CE edited by Joshua Schwartz and Peter J. Tomson [Compendia Hegel's Social Ethics: Religion, Conflict, and Rituals Rerum Iudaicarum Ad Novum Testamentum, Brill, of Reconciliation by Molly Farneth [Princeton 9789004349865] University Press, 9780691171906] The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 7, The After Hegel: German Philosophy, 1840–1900 by Early Modern World, 1500-1815 edited by Frederick C. Beiser [Princeton University Press, Jonathan Karp and Adam Sutcliffe 9780691163093] The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 8, The The World as Transmitting Medium: Theorie eines Modern World, 1815-2000 edited by Mitchell B. Meta-Mediums bei Alfred North Whitehead by Hart and Tony Michels [The Cambridge History of Matthias Götzelmann [Film - Medium - Diskurs, Judaism, Cambridge University Press, Königshausen & Neumann, 9783826064692] text 9780521769532] in German The Jewish Museum: History and Memory, Identity Sefer Yesirah and Its Contexts: Other Jewish Voices and Art from Vienna to the Bezalel National by Tzahi Weiss [Divinations: Rereading Late Museum, Jerusalem by Natalia Berger [Brill, Ancient Religion, University of Pennsylvania Press, 9789004353879] -

Intergenerational Memory, Language and Jewish Identification of the Sarajevo Sephardim

INTERGENERATIONAL MEMORY, LANGUAGE AND JEWISH IDENTIFICATION OF THE SARAJEVO SEPHARDIM REFLECTIONS ON BELONGING IN BOSNIA- HERZEGOVINA/YUGOSLAVIA, ISRAEL AND SPAIN Jonna Rock Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Sprach- und literaturwissenschaftliche Fakultät Institut für Slawistik und Hungarologie Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Christian Voß 2. Prof. Dr. David L. Graizbord Datum der Verteidigung: 20.02.2019 Funding This work was supported by ERNST LUDWIG EHRLICH STUDIENWERK Acknowledgements Above all, I would like to thank my interviewees in Sarajevo – Matilda Finci, Erna Kaveson Debevec, Laura Papo Ostojić, Yehuda Kolonomos, Igor Kožemjakin, Tina Tauber, Vladimir Andrle, A.A. and Tea Abinun – for sharing their reflections with me. I moreover express gratitude for the consultation I have had with Jakob Finci, the president of the Sarajevo Jewish Community, Dr Eliezer Papo, its non-residential rabbi, Elma Softić Kaunitz, its secretary general, and Dr Eli Tauber, who is responsible for the Community’s cultural activities. Further, I am most grateful to my first PhD supervisor, Professor Christian Voß, for his patience with the working process and extremely helpful and encouraging feedback and inspiring suggestions. Professor Voß did not only offer constructive comments on my work but also provided a creative and stimulating academic environment within his Lehrstuhl. He introduced me to a number of experts in my field of study (Professor Ivana Vučina Simović, Professor Kateřina Králová, Professor Jolanta Sujecka, among others), and he gave me an opportunity to participate in and/or organize international conferences, workshops and research seminars. Without Professor Voß’ expertise and guidance throughout my doctoral research (2014-2018), this endeavour would not have been possible. -

Haggadah: Why Is This Book Different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2Nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson

Haggadah: why is this book different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson What is this book? Arthur Szyk (Polish, 1894-1951) Hagadah shel Pesaḥ 1960 Jerusalem: Masadah; Tel Aviv: Alumot BM675.P4M64 1960 Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Saul Raskin, Illustrator Haggadah shel Pesah 1941 Academy Photo Offset BM675.P4Z55667 1941 Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica A Haggadah Happening: an artistic Passover Haggadah … Illustrated by students of the Ann Belsky Moranis School of Art 1998 Ohr Torah Stone Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Gift of Rabbi Martin Sandberg Marc Chagall, Illustrator (Russian, 1887-1985) Chagall’s Passover Haggadah 1987 Leon Amiel BM675.P4A3 1987 Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica How has this book been adapted? E. M. Broner, Editor (1927-2011) The Women’s Haggadah 1994 HarperSanFrancisco Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica The Union Haggadah: home service for the Passover 1923 (revised edition) The Central Conference of American Rabbis Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Haggadah for Children 1952 Bloch Publishing Co., Inc. Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Haggadah for the American Family English service written by Martin Berkowitz 1958 H. Levitt Publishing Co. Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Offenbacher Haggadah 1927 Offenbach am Main: Guggenheim Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica How has this book been used? Seder Ha-Hagadah shel Pesah 1884 (L. Blum edition) M. Lipschütz Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica Leonard -

Eli Collected Passover Stories

Eli Rubenstein Collected Passover Seder Stories My Dog, Elijah David, a nine year old boy living in Canada, tells the exciting tale about his dog Elijah We have a dog named Elijah. He is a very special dog. Now you are probably wondering why he is so special... and you are also probably wondering why he is called Elijah. So, I’ll tell you. It was actually my sister Rebecca's idea and it all goes back to one Passover, several years ago. Now Passover is our favorite holiday – and not just because we get to miss a few days of school!! [During the entire holiday of Passover, we try not to eat any bread – just Matzah, which is a thin large wafer made from wheat. This is to remind us of the time many years ago when the Jewish people were freed from slavery in Egypt. During their escape the Jews could not wait for their dough to rise and turn into bread. So instead they baked Matzah, which is much quicker to make since you don’t have to wait for the dough to rise.] Before the holiday, we always clean up the house from top to bottom, being especially careful to throw away any crumbs of bread we might find. And Mom and Dad start preparing all sorts of strange and interesting foods for the eight day holiday. Then, on the day before Passover, we take a candle and a feather and search for any pieces of bread we might have missed. And then comes the Passover Seder. -

The Pesach Feast1 by Erich Töplitz, Frankfurt A. M. the Illustrations Are

The Pesach Feast1 by Erich Töplitz, Frankfurt a. M. The illustrations are from the exemplary sample collection of the Gesellschaft zur Erforschung jüdischer Kunstdenkmäler, Frankfurt am Main The Pesach or Passover feast is celebrated for eight (in Palestine only seven) days starting on the 15th of Nissan in remembrance of the Jewish homes being passed over during the slaying of the firstborn in Egypt and of the subsequent liberation from suppression in Pharaoh’s country. Because of the hasty exodus, it was not possible to leaven the bread for the journey and, hence, the unleavened bread, “matzah,” was kept as the feast’s symbol. At the time of the Temple, the Pesach sacrifice was at the center of the ceremonies; in the wake of its destruction, a domestic celebration evolved, the Seder (order), which is accompanied by various symbolic activities and by the savoring of symbolic dishes. It takes place on the first two evenings (in Palestine only on the eve) of the feast and is observed by reciting the story of the exodus from Egypt and various psalms and prayers that are read from a small book, the Haggadah (narration). * The Seder Table and its Utensils Among the utensils, the Seder plate, on which the three matzoth are placed, must be mentioned above all. This round flat dish is usually made from conventional pewter, similar to the Purim plate, with which it is frequently confused. Like the latter, it is covered with an abundance of engravings; Seder keywords, important sentences from the Haggadah, pictures of the exodus from Egypt, the Ten Plagues, and the four questioning children, the Passover lamb, and the baking of the matzoth, the story of the little lamb, etc.