Worship-Worthiness and Absolute Perfection: Towards an Account of Supreme Worship-Worthiness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

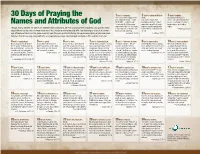

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

The Correlation Between Theology and Worship

Running head: THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP The Correlation Between Theology and Worship Tyler Thompson A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 1 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Rick Jupin, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Keith Cooper, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ David Wheeler, P.H.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Chris Nelson, M.F.A. Assistant Honors Director THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 2 ______________________________ Date Abstract This thesis will address the correlation between theology and worship. Firstly, it will address the process of framing a worldview and how one’s worldview influences his thinking. Secondly, it will contrast flawed views of worship with the biblically defined worship that Christ calls His followers to practice. Thirdly, it will address the impact of theology in the life of a believer and its necessity and practice in the lifestyle of a worship leader. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 3 The Correlation Between Worship and Theology Introduction Since creation, mankind was designed to devote its heart, soul, and mind to the Sovereign God of all (Rom. 1:18-20). As an outward sign of this commitment and devotion, mankind would live in accordance with the established, inerrant, and absolute truths of God (Matt. 22:37, John 17:17). Unfortunately, as a consequence of man’s disobedience, many beliefs have arisen which tempt mankind to replace God’s absolute truth as the basis of their worldview (Rom. -

A Students Guide to the 'Philosophy of Worship in Islam'

A STUDENTS GUIDE TO THE ‘PHILOSOPHY OF WORSHIP IN ISLAM’ DR FAZL-UR- RAHMAN ANSARI BY ABDULLAH CONCEPT OF WORSHIP UNIQUENESS The concept of worship in Islam is unique among the religions of the world. IMPLICATION The word which the Holy Qur’an has used for worship is ‘ibadat, Which means: 1. Submission to God, 2. Service to Him. The word “worship” denotes: in the English language what is termed as “adoration.” The word “ibadat” denotes: the act of becoming ‘abd, namely, slave1. Consequently, the full connotation of the term ‘ibadat’ is to hand over or deliver oneself solely to God. In other words, the worshipper has to negate himself entirely and affirm the supremacy and absolute authority of God in all respects. 1 According to Islamic terminology, this term does not refer to slavery in terms of imprisonment, rather, it refers to Servitude in terms of service. Namely, service in reference to his Creator through whom he attains true freedom, instead of becoming a slave unto himself or others. THE SCOPE OF WORSHIP A HOLISTIC SCOPE OF WORSHIP 1. Worship forms only a part of human life in other religions. 2. In Islam it is meant to cover the whole life.2 2 The purpose behind the creation of man is ‘ibadat’ (worship) as mentioned above, which implies the act of becoming and remaining an Abd (one who lives a life of service in accordance to the Will of God). As many faculties and powers man possesses that many ways and modes of expression manifest. Utilizing each faculty in accordance to the function bestowed upon it will be regarded as worship in terms of Shukr (gratitude), while, misusing any of the faculties will be regarded as Kufr (ingratitude). -

Christian Afterlife

A contribution to the Palgrave Handbook on the Afterlife, edited by Benjamin Matheson1 and Yujin Nagasawa. Do not cite without permission. Comments welcome. CHRISTIANITY AND THE AFTERLIFE Joshua R. Farris, Houston Baptist University https://www.academia.edu/21851852/CHRISTIANITY_AND_THE_AFTERLIFE “I remain confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.” (Psalm 27:13) “I eagerly expect and hope that I will in no way be ashamed, but will have sufficient courage so that now as always Christ will be exalted in my body, whether by life or by death. For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain.” (Philippians 1:20-21) “As all Christians believe in the resurrection of the body and future judgment, they all believe in an intermediate state. It is not, therefore, as to the fact of an intermediate state, but as to its nature that diversity of opinion exists among Christians.” (Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, Part IV. Ch. 1 “State of the Soul after Death,” 724) Lisa is a middle-aged female who has worked all of her life as a server in a cafe. One day, while its rainy and cold, she has a car accident with an 18-wheeler truck. The truck slams into the side of her car pressing her against the side rails. She loses a lot of blood and is rushed to the hospital. Her husband meets her there. Realizing that it is too late and that death is near, he comforts her with these words, “your pain will be gone soon.” June is 90 years old. -

Worshipping the Father with Our Whole Soul

Worshiping our Father on four levels of cosmic Reality Julian McGarry, Hobart, Tasmania Presented at the Tasmanian Conference, October 2010 What is this experience that we call “worship”? What happens to us when we worship? What’s actually going on inside when we worship? At what level of reality do we worship? We are talking here about the ultimate human experience! The Urantia Book constantly emphasizes that our faith is not based on knowing about God, but is to be a personal experience of God – actually knowing God! We are talking about God-consciousness! Touching the Divine! Again and again the UB admonishes us to personally experience God – to have a personal relationship with God. How do we do this? Worship--the spiritual domain of the reality of religious experience, the personal realization of divine fellowship, the recognition of spirit values, the assurance of eternal survival, the ascent from the status of servants of God to the joy and liberty of the sons of God. This is the highest insight of the cosmic mind, the reverential and worshipful form of the cosmic discrimination. – P.192:4 Worship involves the mind!....working at the highest level of discrimination. But that’s just the beginning! The spirit of the Father speaks best to man when the human mind is in an attitude of true worship….. Worship is a transforming experience whereby the finite gradually approaches and ultimately attains the presence of the Infinite. P.1641:1 But how is this possible? The great challenge to modern man is to achieve better communication with the divine Monitor that dwells within the human mind. -

On the Argument for Divine Timelessness from the Incompleteness of Temporal Life William Lane Craig

On the Argument for Divine Timelessness from the Incompleteness of Temporal Life William Lane Craig SUMMARY A promising argument for divine timelessness is that temporal life is possessed only moment by moment, which is incompatible with the existence of a perfect being. Since the argument is based on the experience of time's passage, it cannot be circumvented by appeal to a tenseless theory of time. Neither can the argument be subverted by appeals to a temporal deity's possession of a specious present of infinite duration. Nonetheless, because the argument concerns one's experience of time's passage rather than the objective reality of temporal becoming itself, it is considerably weakened by the fact that an omniscient being possessing perfect memory and foreknowledge need not find such experience to be an imperfection. ON THE ARGUMENT FOR DIVINE TIMELESSNESS FROM THE INCOMPLETENESS OF TEMPORAL LIFE In his study of time and eternity, [1] Brian Leftow argues that the fleeting nature of temporal life provides grounds for affirming that God is timeless. Drawing on Boethius's characterization of eternity as complete possession all at once of interminable life, Leftow points out that a temporal being is unable to enjoy what is past or future for it. The past is gone forever, and the future is yet to come. The passage of time renders it impossible for any temporal being to possess all its life at once. Even God, if He is temporal, cannot reclaim the past. Leftow emphasizes that even perfect memory cannot substitute for actuality: "the past itself is lost, and no memory, however complete, can take its place-- for confirmation, ask a widower if his grief would be abated were his memory of his wife enhanced in vividness and detail." [2] By contrast a timeless God lives all His life at once and so suffers no loss. -

Religion As a Virtue: Thomas Aquinas on Worship Through Justice, Law

RELIGION AS A VIRTUE: THOMAS AQUINAS ON WORSHIP THROUGH JUSTICE, LAW, AND CHARITY Submitted by Robert Jared Staudt A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate in Theology Director: Dr. Matthew Levering Ave Maria University 2008 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: THE CLASSICAL AND PATRISTIC TRADITION CHAPTER TWO: THE MEDIEVAL CONTEXT CHAPTER THREE: WORSHIP IN THE WORKS OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS CHAPTER FOUR: JUSTICE AS ORDER TO GOD CHAPTER FIVE: GOD’S ASSISTANCE THROUGH LAW CHAPTER SIX: TRUE WORSHIP IN CHRIST CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY ABBREVIATIONS 2 INTRODUCTION Aquinas refers to religion as virtue. What is the significance of such a claim? Georges Cottier indicates that “to speak today of religion as a virtue does not come across immediately as the common sense of the term.”1 He makes a contrast between a sociological or psychological evaluation of religion, which treats it as “a religious sentiment,” and one which strives for truth.2 The context for the second evaluation entails both an anthropological and Theistic context as the two meet within the realm of the moral life. Ultimately, the study of religion as virtue within the moral life must be theological since it seeks to under “the true end of humanity” and “its historic condition, marked by original sin and the gift of grace.”3 Aquinas places religion within the context of a moral relation to God, as a response to God’s initiative through Creation and 4 Redemption. 1 Georges Cardinal Cottier. “La vertu de religion.” Revue Thomiste (jan-juin 2006): 335. 2 Joseph Bobik also distinguished between different approaches to the study of religion, particularly theological, philosophical, and scientific, all of which would give different answers to the question “what is religion?.” Veritas Divina: Aquinas on Divine Truth: Some Philosophy of Religion. -

25 Million Names for God

Home Group Worship Resources 25 Million Names for God Appropriate for: Helping your whole group to pray Good for: Prayers of praise and times of worship (adoration). You will need 1) A printout of the sheet 25 million images for each person. Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘I am has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations. (Ex. 3:13-15) Pray Like this: Our FATHER who art in heaven, hallowed be your NAME (Matt 6:9) So that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Phil 2:10-11) INSTRUCTIONS Give everyone a copy of the sheet. Ask people to spend a few minutes reading through the words on the sheet- then to chose one word which stands out personally to them from each column. Have a time of prayer and ask each person to pray a simple one-line prayer: “You are my……………” (followed by the four words they’ve chosen) You could follow this with any/all of the following… CD music or Internet video about God’s name (search you Tube ‘the name of God’ see link below). -

Study of Discrimination in the Matter of Religious Rights and Practice

STUDY OF DISCRIMINATION IN THE MATTER OF RELIGIOUS RIGHTS AND PRACTICES by Arcot Krishnaswami Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities UNITED NATIONS STUDY OF DISCRIMINATION IN THE MATTER OF RELIGIOUS RIGHTS AND PRACTICES by Arcot Krishnaswami Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities UNITED NATIONS New York, 1960 Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. E/CN.4/Sub.2/200/Rev. 1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Catalogue No.: 60. XIV. 2 Price: $U.S. 1.00; 7/- stg.; Sw. fr. 4.- (or equivalent in other currencies) NOTE The Study of Discrimination in the Matter of Religious Rights and Practices is the second of a series of studies undertaken by the Sub- Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities with the authorization of the Commission on Human Rights and the Economic and Social Council. A Study of Discrimination in Education, the first of the series, was published in 1957 (Catalogue No. : 57.XIV.3). The Sub-Commission is now preparing studies on discrimination in the matter of political rights, and on discrimination in respect of the right of everyone to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. The views expressed in this study are those of the author. m / \V FOREWORD World-wide interest in ensuring the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion stems from the realization that this right is of primary importance. -

Theism and the Scope of Contingency

6 Theism and the Scope of Contingency Timothy O’Connor According to classical theism, contingent beings find the ultimate explanation for their existence in a maximally perfect, necessary being who transcends the natural world and wills its acts in accordance with reasons. I contend that if this thesis is true, it is likely that contingent reality is vastly greater than what current scientific theory or even speculation fancies. After considering the implications of this contention for the extent of divine freedom, I go on to discuss its relevance to the problem of evil as an obstacle to rational theistic belief. I. HOW MANY UNIVERSES WOULD PERFECTION REALIZE? In classical philosophical as well as religious theology, God is a personal being perfect in every way: absolutely independent of everything, such that nothing exists apart from God’s willing it to be so; unlimited in power and knowledge; perfectly blissful, lacking in nothing needed or desired; morally perfect. If such a being were to create, on what basis would He choose? Since there is a universe, we know that God did not in fact opt not to create anything at all. But was it really an open possibility that He might have done so? There is a strong case to be made that a per- fect being would create something or other, though it is open to Him to create any of a number of contingent orders. Norman Kretzmann Versions of all or part of this paper were read at the following universities: Oxford, Beijing, Western Washington, Colorado at Boulder, St. Louis, Azusa Pacific, and Trinity College, Dublin. -

Die Phantasie Gottes: an Analysis of the Divine Ideas in Deity Theories & Brian Leftow, with a Proposed Synthesis

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY DIE PHANTASIE GOTTES: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DIVINE IDEAS IN DEITY THEORIES & BRIAN LEFTOW, WITH A PROPOSED SYNTHESIS MASTER’S THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE MASTER OF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES BY NATHAN AUSTIN DOWELL The poet's eye, in fine frenzy rolling, Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven; And as imagination bodies forth The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing A local habitation and a name. - Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream, 5.1.12-17. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Brian Leftow first of all. The chances of him ever becoming aware of anything here are very small but I have to acknowledge him, nonetheless. From everything I have read and seen in lectures, he appears to be a brilliant, original and thorough thinker. His intellectual rigor, humility and passion for God and His supremacy in all things make him a preeminent Christian philosopher for a philosophy student like myself to strive to imitate in my work. It is unfortunate that tone can be lost in writing so I ask the reader to subliminally preface all my critical remarks of his work with a sincere “with all due respect.” I owe a great debt here to Leibniz, Kant, and Spinoza, three prolific German thinkers in whose honor I made the title for this thesis. They both set me on this path (Leibniz) and caused me to change directions while on it (Kant and Spinoza). Some personal friends and family: my dad for his passion for Christ and doing his best to impart that to me; my brothers Joseph and David for their support and insight in conversations on these issues; Scott Panida, one of the most encouraging and inquisitive men I know; Brendan Hegarty for thoughtful conversations; Jonathan Wells, Joseph Gibson, Matt Nevius, Will Green, Shaun Smith and Canaan Suitt, who not only all spoke with me about and/or read over sections of this paper but who also made my time in the M.A.P.S. -

Worship in the Old Testament

Leaven Volume 6 Issue 1 Worship Article 4 1-1-1998 Worship in the Old Testament Phillip McMillion Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Recommended Citation McMillion, Phillip (1998) "Worship in the Old Testament," Leaven: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. McMillion: Worship in the Old Testament 8 Leaven. Winter, 1998 WORSHIP IN THE OLD TESTAMENT Phillip McMillion Meaningful worship is what all Christians seek when God is holy, serving him is not to be taken lightly (vv.I9- they worship God. But what is "meaningful" worship, and 20). A commitment to God is serious, and can even be what makes it so? Where do we turn to find guidance for dangerous if it is not honored. God is holy in a unique and making our worship more meaningful? In his study Wor- special way. In 1 Sam 2:2 we find, "There is none holy ship in Ancient Israel, H. H. Rowley wrote, "The real like the Lord." What does all this mean? It means that meaning of worship derives in the first place from the Israel recognized that there was something unique and dif- God to whom it is directed.": When we begin to consider ferent about their God.