Experts, Intellectuals, and Culture Bubble ‘Standardizing’ from Above

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective Engin I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-9-2011 European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective Engin I. Erdem Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11120509 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Erdem, Engin I., "European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 486. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/486 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AND DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION: SPAIN, POLAND AND TURKEY IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Engin Ibrahim Erdem 2011 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences choose the name of dean of your college/school choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by Engin Ibrahim Erdem, and entitled European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Ronald Cox _______________________________________ Dario Moreno _______________________________________ Barry Levitt _______________________________________ Cem Karayalcin _______________________________________ Tatiana Kostadinova, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 9, 2011 The dissertation of Engin Ibrahim Erdem is approved. -

Forty Years from Fascism: Democratic Constitutionalism and the Spanish Model of National Transformation Eric C

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 2018 Forty Years from Fascism: Democratic Constitutionalism and the Spanish Model of National Transformation Eric C. Christiansen Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation 20 Or. Rev. Int'l L. 1 (2018) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES ERIC C. CHRISTIANSEN* Forty Years from Fascism: Democratic Constitutionalism and the Spanish Model of National Transformation Introduction .......................................................................................... 3 I. Constitutional and Anticonstitutional Developments in Spanish History ......................................................................... 6 A. The Constitution of Cádiz .................................................. 7 B. The Constitution of 1931 ................................................... 9 C. Anticonstitutionalism: The Civil War and Francoist Spain ................................................................................ 10 D. Transitioning to the Transformation ................................ 15 II. A Modern Spanish -

Spain: Constitutional Transition Through Gradual Accommodation of Territories

Spain: Constitutional Transition through Gradual Accommodation of Territories Luis Moreno César Colino Angustias Hombrado © Forum of Federations, 2019 ISSN: 1922-558X (online ISSN 1922-5598) Occasional Paper Series Number 37 Spain: Constitutional Transition through Gradual Accommodation of Territories By Luis Moreno, César Colino and Angustias Hombrado For more information about the Forum of Federations and its publications, please visit our website: www.forumfed.org. Forum of Federations 75 Albert Street, Suite 411 Ottawa, Ontario (Canada) K1P 5E7 Tel: (613) 244-3360 Fax: (613) 244-3372 [email protected] Spain: Constitutional Transition through Gradual Accommodation of Territories 3 Overview Spain’s peaceful transition to democracy (1975-79) offers an example of how a political agreement could overcome internal confrontations. In contemporary times, Spain experienced a cruel Civil War (1936-39) and a long period of dictatorship under General Franco’s rule (1939-75). At the death of the dictator, the opposition mobilized around left-right cleavages as well as around several territorially- based nationalist movements that had been repressed by Francoism. The moment of constitutional transition, which would last from 1977 to 1979, arose from an alliance between moderate reform factions in the elites of the old dictatorship, supported by the new King, with opposition elites. Together, they agreed to call for elections and establish a full-fledged democratic regime amidst a great economic crisis, intense public mobilization and some instances -

The Political Consequences

The Political Consequences of the Great Recession in Southern Europe Crisis and Representation in Spain Guillem Vidal Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, 13 June 2019 ii European University Institute Department of Political and Social Sciences The Political Consequences of the Great Recession in Southern Europe Crisis and Representation in Spain Guillem Vidal Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Hanspeter Kriesi, European University Institute (Supervisor) Prof. Elias Dinas, European University Institute Prof. Eva Anduiza, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Prof. Kenneth M. Roberts, Duke University © Guillem Vidal, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of Political and Social Sciences - Doctoral Programme I Guillem Vidal certify that I am the author of the work The Political Consequences of the Great Recession in Southern Europe: Crisis and Representation in Spain I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

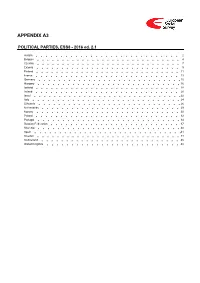

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

PARTY ORGANIZATION, IDEOLOGICAL CHANGE, and ELECTORAL SUCCESS a Comparative Study of Postauthoritarian Parties

PARTY ORGANIZATION, IDEOLOGICAL CHANGE, AND ELECTORAL SUCCESS A Comparative Study of Postauthoritarian Parties Grigorii V. Golosov Working Paper #258 - September 1998 Grigorii V. Golosov teaches comparative politics at the European University at St. Petersburg, Russia. He was a Visiting Fellow at the Kellogg Institute during the 1998 spring semester. Professor Golosov obtained an MA in Russian History and a PhD in Social Philosophy at Novosibirsk State University, an MA in Political Science from SUNY/Central European University, Budapest, and postgraduate study diplomas from the University of Oslo and Southern Illinois University. He has also been a Research Associate at the Center for Slavic and East European Studies, University of California at Berkeley, and a Visiting Scholar at the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Woodrow Wilson Center, and the Institute of Russian and East European Studies, St. Antony’s College, Oxford University. In support of his research, he has been awarded grants from the USIA and the MacArthur and Soros Foundations. His most recent publications include Modes of Communist Rule, Democratic Transition, and Party System Formation in Four East European Countries (University of Washington, 1996); “Russian Political Parties and the ‘Bosses’: Evidence from the 1994 Provincial Elections in Western Siberia,” Party Politics (1997); “Regional Party System Formation in Russia: The Deviant Case of Sverdlovsk Oblast,” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics (with Vladimir Gelman, forthcoming); and “Who Survives? Party Origins, Organizational Structure, and Electoral Performance in Post- Communist Russia,” Political Studies (forthcoming). He has also published several books and many articles in Russian. I would like to thank the Helen Kellogg Institute for granting me a residential fellowship that made my research possible. -

From Authoritarian Rule Toward Democratic Governance: Learning from Political Leaders

FFromrom aauthoritarianuthoritarian rruleule ttowardoward ddemocraticemocratic ggovernance:overnance: LLearningearning ffromrom ppoliticalolitical lleaderseaders Abraham F. Lowenthal and Sergio Bitar © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2015 International IDEA Strömsborg, SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 E-mail: [email protected], website: www.idea.int International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. This material is drawn from International IDEA, Democratic Transitions: Conversations with World Leaders, eds S. Bitar and A. Lowenthal (Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, Forthcoming, 2015) CContentsontents Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 From authoritarian rule toward democratic governance: Learning from political leaders ......................... 8 The broad contours of nine successful transitions ...................................................................................... 10 Recurrent challenges of transitions ............................................................................................................. 18 Learning from political leaders ................................................................................................................... -

Hannah Arendt and the Problem of Democratic Revolution

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Hannah Arendt and the Problem of Democratic Revolution A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science John Louis LeJeune Committee in charge: Professor Tracy B. Strong, Chair Professor Harvey Goldman Professor Gerry Mackie Professor Richard Madsen Professor Philip Roeder 2014 Copyright John Louis LeJeune, 2014 All rights reserved. The dissertation of John Louis LeJeune is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my aunt, Melanie Maria LeJeune (1965-2013), who was a mother to all, and to Wang Ke, of two! iv Epigraph The ceaseless, senseless demand for original scholarship in a number of fields, where only erudition is now possible, has led either to sheer irrelevancy, the famous knowing of more and more about less and less, or to the development of pseudo-scholarship which actually destroys its object. Hannah Arendt 1972 v Table of Contents Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………………….. iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………………... iv Epigraph………………………………………………………………………………………………... v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………... vii Vita………………………………………………………………………………………………………... viii Abstract of the Dissertation….……………...…………………………………………………. ix Chapter I: Revolutionary Narrative and the Twentieth -

Reshaping the Concepts of State and Community in the Thought of Manuel Fraga

genealogy Article Spanish Conservatives at the Early Stages of Spanish Democracy: Reshaping the Concepts of State and Community in the Thought of Manuel Fraga Enrique Maestu Fonseca Ciencia Política, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28223 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] Received: 10 December 2019; Accepted: 25 February 2020; Published: 28 February 2020 Abstract: This article focused on the evolution of Spanish conservative doctrine in the early years of democracy in Spain. By analyzing the concepts of ‘state’ and ‘community’ in the thought of Manuel Fraga, the Minister of Information and Tourism under the Franco dictatorship and leader of the Spanish right during the 1980s, this article sought to explore: the manner in which the conservatives sought to “democratize” their doctrine to adapt themselves to the new party system and the importance of this conceptual reshaping in establishing the roots of conservative Spanish nationalism. Keywords: Spanish conservatives; nationalism; authoritarism; regime-changing; political culture; Spanish transition; Alianza Popular; Manuel Fraga 1. Introduction The changes in political regimes, and in particularly transitions from authoritarian systems into parliamentary democracies, involve a set of agreements in order to establish a shared regulatory framework that sustains the architecture of the new regime, but also a subsequent reshaping of the political landscape and political party legitimation. In the Spanish case, the idea of consensus and agreement during the transitional period has been highlighted in numerous works (Juliá 2019; Tusell 2005). The consensus was forged among the main political forces from the opposition and the “opening sector” (aperturistas) of the dictatorship who were willing to prepare the transition towards a pluralistic democratic system band a new constitutional framework. -

2005 – the Politics of Contemporary Spain

The Politics of Contemporary Spain The Politics of Contemporary Spain charts the trajectory of Spanish politics from the transition to democracy through to the present day, including the aftermath of the Madrid bombings of March 2004 and the elections that followed three days later. It offers new insights into the main political parties and the political system, into the monarchy, corruption, terrorism, regional and conservative nationalism and into Spain’s policies in the Mediterranean and the European Union. It challenges many existing assumptions about politics in Spain, reaching beyond systems and practices to look at identities and political cultures. It brings to bear on the analysis the latest empirical data and theoretical perspectives. Providing a detailed political analysis in an historical context, this book is of vital importance to students and researchers of Spanish studies and politics. It is also essential reading for all those interested in contemporary Spain. Sebastian Balfour is Professor of Contemporary Spanish Studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research interests cover the history and politics of twentieth-century Spain. Recent publi- cations include: The End of the Spanish Empire 1898–1923 and Deadly Embrace: Morocco and the road to the Spanish Civil War. The Politics of Contemporary Spain Edited by Sebastian Balfour First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. -

Spain – out with the Old: the Restructuring of Spanish Politics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Vidal, Guillem; Sánchez-Vítores, Irene Book Part — Published Version Spain – Out with the Old: The Restructuring of Spanish Politics Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Vidal, Guillem; Sánchez-Vítores, Irene (2019) : Spain – Out with the Old: The Restructuring of Spanish Politics, In: Hutter, Swen Kriesi, Hanspeter (Ed.): European party politics in times of crisis, ISBN 978-1-108-65278-0, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 75-94, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781108652780.004 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/210475 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu 4 Spain – Out with the Old: The Restructuring of Spanish Politics Guillem Vidal and Irene Sánchez-Vítores 4.1 Introduction To paraphrase Polanyi (1944), there are certain critical periods during which time expands.