Hannah Arendt and the Problem of Democratic Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Science 41/Classics 45/Philosophy 41 Western Political Thought I Tufts University Fall Semester 2011

Political Science 41/Classics 45/Philosophy 41 Western Political Thought I Tufts University Fall Semester 2011 Socrates is said to have brought philosophy down from the heavens to examine “the human things.” This course will examine the revolution in Western thought that Socrates effected. In the process, we will study such topics as the manner in which political communities are founded and sustained, the claims for virtue, the various definitions of justice, the causes and ramifications of war, the relation between piety and politics, the life of the philosopher, and the relation between philosophy and politics. Finally, we will examine Machiavelli’s challenge to classical political thought when he charges that imaginary republics—some of which we will have studied—have taught people their ruin rather than their preservation. Office Hours Vickie Sullivan [email protected] Packard Hall 111, ex. 72328 Monday, 1:30-3 p.m. Thursday, 1-2:30 p.m. Other times by appointment Teaching Assistants Nate Gilmore [email protected] Tuesday, 12-1:30 p.m. Packard Hall, 3rd-floor lounge Other times by appointment Mike Hawley [email protected] Wednesday, 12-1:30 p.m. Packard Hall, 3rd-floor lounge Other times by appointment Required Books Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, ed. Robert B. Strassler, Touchstone (Simon & Schuster). Plato and Aristophanes, Four Texts on Socrates, trans. Thomas West and Grace Starry West, Cornell University Press. 2 Plato, Symposium, trans. Seth Benardete, University of Chicago. Plato, Republic, trans. Allan Bloom, Basic Books. Aristotle, The Politics, trans. Carnes Lord, University of Chicago Press. Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. -

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

3 Reading Arendt's on Revolution After the Fall of the Wall

3 READING ARENDT’S ON REVOLUTION AFTER THE FALL OF THE WALL Dick Howard* RESUMO – O artigo revisita a obra de Hannah ABSTRACT – The article revisits Hannah Arendt’s Arendt On Revolution e os eventos históricos da On Revolution and the historical events of the revolução americana, de forma a reformular os American revolution so as to recast what Arendt chamados “problemas da época”. Embora todo ator called “the age’s problems”. Although every político reivindique que as suas políticas sejam a political actor claims that its policies are the encarnação da vontade unida da nação em uma incarnation of the united will of the nation in a democracia, abre-se a porta da antipolítica na democracy, the door to antipolitics is opened if the medida em que a natureza simbólica – e portanto symbolic – and therefore contested – nature of the contestada – do povo soberano é reduzida à sua sovereign people is reduced to its temporary reality. realidade temporária. Tal é a lição crucial a ser That is the crucial lesson to be drawn still today extraída ainda hoje da obra The Origins of from The Origins of Totalitarianism, which can be Totalitarianism, que pode ser lida como uma read as an attempt to think the most extreme tentativa de pensar a expressão mais extrema da expression of antipolitics. antipolítica. PALAVRAS-CHAVE – Antipolítica. Arendt. Demo- KEY WORDS – Antipolitics. Arendt. Democracy. cracia. Revolução. Revolution. Introduction: From where do you speak, comrade? Two decades after the fall of the Wall seemed to announce – by default, as an unexpected gift – the triumph of democracy, optimism appears at best naïve, at worst an ideological manipulation of the most cynical type. -

European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective Engin I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-9-2011 European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective Engin I. Erdem Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11120509 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Erdem, Engin I., "European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 486. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/486 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AND DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION: SPAIN, POLAND AND TURKEY IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Engin Ibrahim Erdem 2011 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences choose the name of dean of your college/school choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by Engin Ibrahim Erdem, and entitled European Integration and Democratic Consolidation: Spain, Poland and Turkey in Comparative Perspective, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Ronald Cox _______________________________________ Dario Moreno _______________________________________ Barry Levitt _______________________________________ Cem Karayalcin _______________________________________ Tatiana Kostadinova, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 9, 2011 The dissertation of Engin Ibrahim Erdem is approved. -

Prof. Dr. Dr. Jörg Monar Recteur/Rector 13 November 2019 OPENING CEREMONY ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 Dear President of The

Prof. Dr. Dr. Jörg Monar Recteur/Rector 13 November 2019 OPENING CEREMONY ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 ALLOCUTION PROMOTION HANNAH ARENDT Dear President of the European Council, Dear President of the Administrative Council, Mijnheer de Gouverneur, Mijnheer de Burgermeester, Your Excellencies, Dear Friends and Colleagues, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Students, One of the most well-known and often-cited concepts of political anthropology is Aristotle’s classification of the human being as a ζῷον πολιτικόν, as a “political animal” or perhaps better, “living being”, in his Πολιτικά written around 330 BC. According to him - who we can regard as the father of political science - it is only through man being part of a political community, the πόλις, that he can fully realise his nature and potential. The history of mankind has shown, and our world of today keeps showing, that this political dimension of our existence accounts for much of what we have been able to achieve as humans in terms of social, legal, scientific, economic, organisational and even the moral progress, well beyond the horizons of the Greek city-states which formed the basis of Aristotle’s analysis. Yet at the same time this political dimension has also all too often been a pathway to the abysses of human nature, to unrestrained barbarism and the infliction of boundless suffering by some on their fellow human beings. │Hannah Arendt – PATRONNE OF THE PROMOTION 2019-2020] 2 How can it happen, how can it be explained that what belongs to our essence, what accounts for so much of the positive potential of our living together, the political dimension of our existence, can turn into the large-scale destruction of values and lives, the generation of evils poisoning an entire generation or more? In 1933 a 26-year old, intellectually wide awake and strongly-willed young researcher, Hannah Arendt, was confronted with one of those turns of politics into hell, arguably one if not the most calamitous in history, the coming into power of the Nazi regime in Germany. -

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark The Course consists of 8 lectures, 16 presentation-led seminars and 4 gobbets classes GENERAL READING Jonathan Sperber, The European Revolutions, 1848-1851 (Cambridge, 1994) Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001) Priscilla Smith Robertson, The Revolutions of 1848, a social history (Princeton, 1952) Michael Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (London, 2009) SOCIAL CONFLICT BEFORE 1848 (i) The ‘Galician Slaughter’ of 1846 Hans Henning Hahn, ‘The Polish Nation in the Revolution of 1846-49’, in Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform, pp. 170-185 Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010), esp. chapters 3 & 4 Thomas W. Simons Jr., ‘The Peasant Revolt of 1846 in Galicia: Recent Polish Historiography’, Slavic Review, 30 (December 1971) pp. 795–815 (ii) Weavers in Revolt Robert J. Bezucha, The Lyon Uprising of 1834: Social and Political Conflict in the Early July Monarchy (Cambridge Mass., 1974) Christina von Hodenberg, Aufstand der Weber. Die Revolte von 1844 und ihr Aufstieg zum Mythos (Bonn, 1997) *Lutz Kroneberg and Rolf Schloesser (eds.), Weber-Revolte 1844 : der schlesische Weberaufstand im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Publizistik und Literatur (Cologne, 1979) Parallels: David Montgomery, ‘The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844’ Journal of Social History, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Summer, 1972), pp. 411-446 (iii) Food riots Manfred Gailus, ‘Food Riots in Germany in the Late 1840s’, Past & Present, No. 145 (Nov., 1994), pp. 157-193 Raj Patel and Philip McMichael, ‘A Political Economy of the Food Riot’ Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 32/1 (2009), pp. -

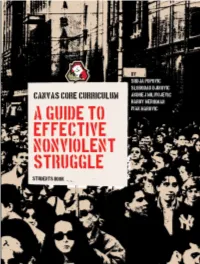

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

Reading Arendt's on Revolution After the Fall of the Wall

Keeping the Republic: Reading Arendt’s On Revolution after the Fall of the Wall Dick Howard Introduction: From where do you speak, comrade? Two decades after the fall of the Wall seemed to announce – by default, as an unexpected gift – the triumph of democracy, optimism appears at best naïve, at worst an ideological manipulation of the most cynical type. The hope was that the twin forms of modern anti-politics – the imaginary planned society and the equally imaginary invisible hand of the market place – would be replaced by the rule of the demos; citizens together would determine the values of the commonwealth. The reality was at first the ‘New World Order’ of George H.W. Bush; then the indecisive interregnum of the Clinton years; and now the crass take over of democratic rhetoric by the neo-conservatives of George W. Bush. ‘Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains,’ wrote Rousseau at the outset of The Social Contract; how this came about was less important, he continued, than what made it legitimate: that was what needed explanation. So it is today; what is it about democracy that makes it the greatest threat to its own existence? In this context, it is well to reread Hannah Arendt’s On Revolution, published in 1963. On returning recently to my old (1965) paperback edition, I was struck by the spare red and black design of the cover, which was not (as I thought for a moment) a subtle allusion to the conflict of communism and anarchism for the realization of ‘true’ democracy, but simply the backdrop against which the editor stressed these sentences: ‘With nuclear power at a stalemate, revolutions have become the principal political factor of our time. -

Hard-Rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900

UNPOLISHED EMERALDS IN THE GEM STATE: HARD-ROCK MINING, LABOR UNIONS AND IRISH NATIONALISM IN THE MOUNTAIN WEST AND IDAHO, 1850-1900 by Victor D. Higgins A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2017 © 2017 Victor D. Higgins ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Victor D. Higgins Thesis Title: Unpolished Emeralds in the Gem State: Hard-rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900 Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Victor D. Higgins, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. John Bieter, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jill K. Gill, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Raymond J. Krohn, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by John Bieter, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author appreciates all the assistance rendered by Boise State University faculty and staff, and the university’s Basque Studies Program. Also, the Idaho Military Museum, the Idaho State Archives, the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, and the Wallace District Mining Museum, all of whom helped immensely with research. And of course, Hunnybunny for all her support and patience. iv ABSTRACT Irish immigration to the United States, extant since the 1600s, exponentially increased during the Irish Great Famine of 1845-52. -

Trinitytrinity ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch s Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply fies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or fve years of living and learning and growing and gaining fned the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long afer the place itself has been lef behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire ofce. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Ofce friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Afairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long afer Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

View 2021-2022 Reading List

CALGARY ASSOCIATION OF LIFE LONG LEARNERS HOW CAN YOU THINK THAT? A POLITICAL BOOKCLUB SEPTEMBER 2021 - JUNE 2022 READING LIST ————————————————————————————————————- July - August 2021. “Summer Reads” Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, from Sustainable to Suicidal Mark Bittman "Epic and engrossing."—The New York Times Book Review From the #1New York Times bestselling author and pioneering journalist, an expansive look at how history has been shaped by humanity’s appetite for food, farmland, and the money behind it all—and how a better future is within reach. The story of humankind is usually told as one of technological innovation and economic influence—of arrowheads and atomic bombs, settlers and stock markets. But behind it all, there is an even more fundamental driver: Food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, trusted food authority Mark Bittman offers a panoramic view of how the frenzy for food has driven human history to some of its most catastrophic moments, from slavery and colonialism to famine and genocide—and to our current moment, wherein Big Food exacerbates climate change, plunders our planet, and sickens its people. Even still, Bittman refuses to concede that the battle is lost, pointing to activists, workers, and governments around the world who are choosing well-being over corporate greed and gluttony, and fighting to free society from Big Food’s grip. Sweeping, impassioned, and ultimately full of hope,Animal, Vegetable, Junk reveals not only how food has shaped our past, but also how we can transform it to reclaim our future. Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World Simon Winchester “In many ways, Land combines bits and pieces of many of Winchester’s previous books into a satisfying, globe-trotting whole. -

2016 Gala Dinner Celebrating the 21St Anniversary of the U.S.-China Policy Foundation

2016 Gala Dinner Celebrating the 21st Anniversary of the U.S.-China Policy Foundation Thursday, November 17, 2016 The Mayflower Hotel Washington, D.C. China in Washington Celebrating the 21st anniversary of the U.S.-China Policy Foundation and recognizing honorees for excellence in public service and U.S.-China relations THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2016 This evening has been made possible by the generous support of our sponsors LEAD SPONSORS Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office The Starr Foundation SPONSORS Micron J.R. Simplot Air China SUPPORTERS Wanxiang America China Daily UPS FedEx China Telecom Alaska Airlines RECEPTION Chinese Room, 6:30 - 7:00 PM DINNER & PROGRAM Grand Ballroom, 7:00 - 9:30 PM THE MAYFLOWER HOTEL 1127 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 Program WELCOME REMARKS The Honorable James Sasser U.S. Ambassador to China (1996-1999) U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1977-1995) DINNER SERVICE AWARDS PRESENTATION LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS Dr. David M. Lampton Professor and Director of China Studies, Johns Hopkins SAIS The Honorable Barbara Hackman Franklin President and CEO, Barbara Franklin Enterprises 29th Secretary of Commerce GLOBAL PEACEMAKER AWARD His Excellency Ban Ki-moon 8th Secretary-General of the United Nations DINNER SPEAKER His Excellency Cui Tiankai Chinese Ambassador to the United States (2013-present) CLOSING REMARKS The Honorable J. Stapleton Roy U.S. Ambassador to China (1991-1995) 2016 Gala Honoree LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT IN U.S.-CHINA EDUCATION Dr. David M. Lampton Professor and Director of China Studies, Johns Hopkins SAIS David M. Lampton is Hyman Professor and Director of China Studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, where he also heads SAIS China, the school’s overall presence in greater China.