A Perspective on Embroidery: in Answer to Emery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni I’m including in this handout a couple of different ways of explaining “how-to” in blackwork, because not every explanation works for every person. Also, please excuse the crass commercial plugs. I didn’t have time to completely re-write, so pretend that this somebody else’s. Which it is! Anja and MaryAnne are not the same person. <grin> MaryAnne Bartlett is a 21st century woman, making a living by writing and researching, designing and selling blackwork designs and products. Anja Snihova’ was born in the late 14th century and due to the potions that her alchemist husband makes, survived into the early 17th century! Beginning Blackwork Blackwork is a counted thread technique made popular in England in the 1500's by Catharine of Aragon, the Spanish first wife of King Henry VIII of England. It was immortalized in the incredibly detailed portraits done by the court painter, Hans Holbein, whose name is give to the stitch used, which is just a running stitch that doubles back on itself at the other end of its "journey". Blackwork can be anything from a simple line drawing to the complex pattern of #10 below, and on to designs so complex no one seems to know how to do them! It was usually done with silk thread on a white even-weave linen, and despite the name of the technique, was done in every colour of the rainbow, although black was the most popular colour, followed by red and blue. The most peculiar thing about this technique is that, done properly, the design repeats on both the right and wrong sides of the fabric, making it perfect for collars, cuffs, veils and ribbons where both sides need to look nice! Blackwork Embroidery Instructions 1. -

Medieval Clothing and Textiles

Medieval Clothing & Textiles 2 Robin Netherton Gale R. Owen-Crocker Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 Medieval Clothing and Textiles ISSN 1744–5787 General Editors Robin Netherton St. Louis, Missouri, USA Gale R. Owen-Crocker University of Manchester, England Editorial Board Miranda Howard Haddock Western Michigan University, USA John Hines Cardiff University, Wales Kay Lacey Swindon, England John H. Munro University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada M. A. Nordtorp-Madson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA Frances Pritchard Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Monica L. Wright Middle Tennessee State University, USA Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 edited by ROBIN NETHERTON GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2006 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2006 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 1 84383 203 8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Illustrations page vii Tables ix Contributors xi Preface xiii 1 Dress and Accessories in the Early Irish Tale “The Wooing Of 1 Becfhola” Niamh Whitfield 2 The Embroidered Word: Text in the Bayeux Tapestry 35 Gale R. -

Remembering Ricamo Italian Embroidery

GALLERY76 EXHIBITION GUIDE AN EXHIBITION OVERVIEW CURATOR: APRIL SPIERS AUGUST 2020 WATCH THE LIVE WALKTHROUGH AND CONVERSATION WITH FIBER TALK VIA https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=KF6Gc8AF9VE&feature=youtu.be RETICELLO Reticello (Italian, “small net”) is a variety of needle lace which arose in the 15th century, first recorded in Milan 1493, and remained popular into the 17th century. Reticello was originally a form of cutwork (where threads are pulled from linen fabric to form a grid on which the pattern is stitched primarily using buttonhole stitch) Later reticello used a grid made of thread rather than a fabric ground. Reticello is characterised by a geometric design of squares and circles and geometric motifs and is traditionally worked on white or ecru fabric. It is regarded as a forerunner of punto in aria. One of the contemporary champions of the style is Giuliana Buonpadre who established an Embroidery School in Verona in order to preserve the knowledge and skills involved in traditional Italian embroidery. Under her Karen Little guidance, Giuliana’s students have taken these traditional Reticello techniques and introduced a contemporary twist with the introduction of coloured threads. We have a number of these coloured pieces worked by Guild member Karen Little, along with a number of traditional pieces in this exhibition. Also known as: Greek point; reticello; point coupé; point couppe; radexela; radicelle Tina Miletta PUNTO ANTICO Punto Antico (Italian, “Antique Stitch) dates as far back as the 15th century and was known by a variety of names including Punto Toscano, Punto Reale, and Punto Riccio. The style did not became known as “Punto Antico” until the early 20th century. -

Textile Glossary Astrakhan Fabric: Knitted Or Woven

Textile Glossary Astrakhan fabric: knitted or woven fabric that imitates the looped surface of newborn karakul lambs Armscye: armhole Batiste: the softest of the lightweight opaque fabrics. It is made of cotton, wool, polyester, or a blend. Bertha collar: A wide, flat, round collar, often of lace or sheer fabric, worn with a low neckline in the Victorian era and resurrected in the 1940s Bishop sleeves: A long sleeve, fuller at the bottom than the top, and gathered into a cuff Box pleats: back-to-back knife pleats Brocade: richly decorative woven fabric often made with colored silk Broken twill weave: the diagonal weave of the twill is intentionally reversed at every two warp ends to form a random design Buckram: stiff loosely woven fabric Cambric: a fine thin white linen fabric Cap sleeves: A very short sleeve covering only the shoulder, not extending below armpit level. Cartridge pleat: formed by evenly gathering fabric using two or more lengths of basting stitches, and the top of each pleat is whipstitched onto the waistband or armscye. Chambray fabric: a lightweight clothing fabric with colored (often light blue) warp and white weft yarns Changeable fabric: warp and weft are different colors, when viewed from different angles looks more one color than the other Chemisette: an article of women's clothing worn to fill in the front and neckline of any garment Chiffon: lightweight, balanced plain-woven sheer fabric woven of alternate S- and Ztwist crepe (high-twist) yarns producing fabric with a little stretch and slightly rough texture -

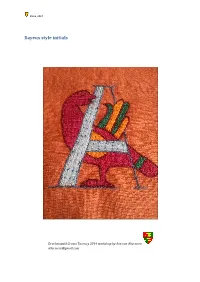

Bayeux Style Initials

©Ava, 2014 Bayeux style initials Drachenwald Crown Tourney 2014 workshop by Ava van Allecmere [email protected] Introduction: The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cloth—not an actual tapestry—nearly 70 metres (230 ft) long, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England concerning William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold, Earl of Wessex, later King of England, and culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The word tapestry comes from French tapisser, which means ‘to cover the wall’, thus wall covering. The tapestry consists of some fifty scenes with Latin tituli (captions), embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns. It is likely that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, William's half- brother, and made in England—not Bayeux—in the 1070s. In 1729 the hanging was rediscovered by scholars at a time when it was being displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral. The tapestry is now exhibited at Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy, France. In a series of pictures supported by a written commentary the tapestry tells the story of the events of 1064–1066 culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The two main protagonists are Harold Godwinson, recently crowned King of England, leading the Anglo-Saxon English, and William, Duke of Normandy, leading a mainly Norman army, sometimes called the companions of William the Conqueror. Construction, design and technique: The Bayeux tapestry is embroidered in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground 68.38 metres long and 0.5 metres wide (224.3 ft × 1.6 ft) and using two methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures. -

Advanced Diploma Academic Year Fine Whitework

ROYAL SCHOOL OF NEEDLEWORK 2019-2020 ADVANCED DIPLOMA ACADEMIC YEAR FINE WHITEWORK ‘Whitework’ encompasses a diverse range of techniques, whose execution spans history from earliest times to the present day, linked by the common theme of neutral threads worked on a neutral ground. The term ‘fine whitework’ can be used to refer to any form of whitework embroidery which has been executed on a fine scale. However, at the RSN, the term refers to a technique which facilitates combining the principal forms of fine scale whitework within one piece of work. This fundamentally allows exploitation of the full potential of the whitework ‘tonal scale’ from solid, sculptural techniques, through to the most translucent or open. AIM – to design and work fine whitework embroidery encompassing key techniques of the whitework tonal scale from solid to open work on one piece of fabric. A fine whitework embroidery demonstrating effectiveness of design for purpose and a high level of skill in execution of the stitches. MATERIALS: The ground cloth is a linen batiste or cambric. Two weights are available to select from: fine and very fine. The necessity to count the linen threads for this work should determine this choice. Two layers of linen will be used in parts of the design, one in others. A layer of net will also be sandwiched between the layers. A choice of fine, nylon conservation net, or heavier cotton bobbinet can be made, again according to ability to count the segments of the net. Threads. The following may be used: white stranded cotton, white cotton à broder (various sizes), white cotton perlé (finer sizes only), DMC floche à broder (for padding only, unless all other threads used are also DMC), Brok Egyptian Cotton lace threads in a range of sizes, Belgian ‘Egyptian Cotton’ lace threads in a range of sizes. -

27Th February – 1St March 2020 Business Design Centre, London

previously A-Z LEARNING CURVE and DRESSMAKING STUDIO AND WORKSHOP DESCRIPTIONS The Learning Curve and Dressmaking Studio Workshops Timetable and Detailed Information 27th February – 1st March 2020 Business Design Centre, London Dressmaking Studio • Workshops range from 1 hour taster sessions to 1.5 hour, 2 hours and 3 hours. Technique classes from basics • All materials you need are included in to couture for all dressmaking levels 1 hour, 1.5 hour and 2 hour sessions (unless otherwise stated). NEW baby lock Workshop Room • Sewing machines are provided where necessary. Learn to use an overlocker NB: Some of the longer classes (3 hour and 1 day) and garment making classes require you to bring More workshops than ever your own materials or pay for a kit on the day. Over 244 classes in 12 dedicated rooms What is needed is included in the course description. Tickets and information: thestitchfestival.co.uk or 0844 854 1349 BOOK EARLY TO AVOID DISAPPOINTMENT! thestitchfestival.co.ukNB: In order to attend any of the thestitchfstvlworkshops, you do also needthestitchfestival to purchase an entry ticket to the show. 1 TIMETABLE Thursday 27th February 2020 Early Morning classes starting at 8.30am or 9am include light refreshments of pastry and tea/coffeeE CODE START TITLE TUTOR ROOM LEVEL LENGTH COST 1 08:30 Knit with Wire: Dancing Spring Daffodils Susan Burns Room 4 I 1.5 hr £29 2 08:30 Everlasting Rag Rug Bouquets Elspeth Jackson, RaggedLife Room 5 AL 1.5 hr £29 3 08:30 Hand Stitched Memory Trinket Box Ami James Room 6 B 1.5 hr £29 4 08:30 Learn -

Silk & Stitch Booklet

Mint Dress, circa 1960s Silk Embellishment: Lace appliqué This mother of the bride wore this dress to her daughter’s wedding. This dress was made by the Internaonal Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), which was founded in 1900 and funconed in the United States and Canada. The lace used mimics alençon lace, which is named aer the town of its origin in France. True alençon lace is made exclusively in Alençon, France. Appliqué is accomplished by sewing or gluing small pieces of fabric to a larger piece to create a design. This technique can be done by hand or by machine. This dress actually has two pockets! This dress is one of only two dresses in this exhibit with pockets. Parachute Dress, circa 1945 Silk, coon embroidery floss Embellishments: Hand embroidered with padded san stch with stem stch This dress was made from a German parachute. The parachute was recovered and brought to the United States by R. T. Burden, Jr., in 1945. Mr. Burden served in the United State Army from 1943 to 1945. Parachutes were made in white and cream in order to conserve fabric dye. Once silk became “military issue” the price went up and women could no longer afford to buy silk. It was common during and aer World War II to see women make wedding dresses and other garments out of parachutes brought back by their husbands or other soldiers. Resource raoning lasted unl well aer the war. Black Beaded Dress, circa 1930s Rayon (or silk) Embellishments: Tambour beading with glass seed beads with glass bugle beads This is a typical evening dress of the 1930s. -

BERNINA Accessories Solutions for Your Ideas

BERNINA Accessories Solutions for your ideas BERNINA Accessories at a a glance BERNINA offers a wide range of sewing, embroidery and quilting accessories. In this brochure you’ll find the appropriate tool for any sewing or embroidery project. A BERNINA 910 1004 1030 1230 930 1005 1031 1240 931 1006 1050 1241 932 1008 1070 1260 | Contents 933 1010 1080 1530 940 1011 1090 1630 950 1015 1091 1000 1020 1120 1001 1021 1130 Number Presser-foot type Page Number Presser-foot type Page B BERNINA activa and 3 Series 125 230 125 S 230PE 135 240 0 Zigzag foot 7 53 Straight-stitch foot with sliding sole 10 135 S 330 0 Zigzag foot 54 Zipper foot with sliding sole 12 145 350 145 S 350PE with finger guard # 99 7 55 Leather roller foot 26 210 380 215 1 / 1C / 1D Reverse pattern foot 8 56 Open embroidery foot with sliding sole 19 220 2 / 2A Overlock foot 8 57 / 57D Patchwork foot with guide 28 C BERNINA virtuosa 3 / 3C Buttonhole foot 14 59 / 59C Double-cord foot (4 – 6mm grooves) 27 150 3A / 3B / 3C Buttonhole foot with slide 14 60 / 60C Double-cord foot (7 – 8mm grooves) 27 153 153 QE 4 / 4D Zipper foot 12 61 2mm zigzag hemmer 16 155 5 Blindstitch foot 9 62 2mm straight-stitch hemmer 15 160 163 6 Embroidery foot 18 63 3mm zigzag hemmer 16 7 Tailor-tack foot 20 64 4mm straight-stitch hemmer 15 8 / 8D Jeans foot 10 66 6mm zigzag hemmer 16 9 Darning foot 30 68 2mm roll and shell hemmer 17 D BERNINA aurora 430 10 / 10C / 10D Edgestitch foot 9 69 4mm roll and shell hemmer 17 440QE 11 Cordonnet foot 20 70 4mm lap seam foot 18 D1 B530 B550QE 12 / 12C Bulky -

A New Way of Seeing the History of Art in 57 Works

A NEW WAY OF SEEING THE HISTORY OF ART IN 57 WORKS KELLY GROVIER Advance Information Thames & Hudson Ltd A New Way of Seeing 181A High Holborn London WC1V 7QX The History of Art in 57 Works T +44 (0)20 7845 5000 Kelly Grovier F +44 (0)20 7845 5052 W www.thamesandhudson.com A new way of appreciating art that puts the artwork front and centre, brought to us by one of the freshest and most exciting new voices in cultural criticism. Frankfurt 2016 Hall 6.1 B126 Marketing points Author • An impassioned exploration of what it is that constitutes great art, Kelly Grovier is a poet, historian through an illuminating analysis of the world’s outstanding masterpieces – and cultural critic. He is a regular works whose power to move transcends the sum of their parts. contributor on art to the Times • Casts fresh new light on some of the most famous works in Literary Supplement, and his the history of art by daring to isolate in each a single (and often writing has appeared in numerous overlooked) detail responsible for its greatness. publications, including the • Grovier’s 100 Works of Art That Will Define Our Age, ‘a daring and Observer, the Sunday Times and convincing analysis of seminal artworks of our age’ (Telegraph), received Wired. Educated at the University exceptional reviews. of California, Los Angeles, and at the University of Oxford, he is Description co-founder of the International BCE scholarly journal European Romantic From a carved mammoth tusk (c. 40,000 ) to Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), Review, as well as the author of 100 and Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1505–10) to Louise Bourgeois’s Works of Art That Will Define Our Age Maman (1999), a remarkable lexicon of astonishing imagery has imprinted and Art Since 1989 (both published itself onto cultural consciousness over the past 40,000 years – a resilient by Thames & Hudson). -

DIPLOMA-Whitework-Drawn-Thread

2018-2019 ROYAL SCHOOL OF NEEDLEWORK ACADEMIC YEAR DIPLOMA WHITEWORK PULLED AND DRAWN THREAD WORK Pulled thread work is a traditional technique in which stitched patterns distort the threads of evenweave linen to create lace-like effects. There is a wide variety of stitch patterns from which to choose. Drawn thread work is a traditional technique in which threads of the evenweave linen are removed and decorative stitches are worked in their place to produce a lace-like effect. There is a wide variety of stitches from which to choose. AIM – to produce a piece of whitework embroidery demonstrating that you have understood the principles of pulled and drawn thread work, you have chosen appropriate stitches for the design and function of the piece, executed the stitches with the clarity and accuracy required in the absence of colour and kept the work clean and fresh during completion. DESIGN The size should be no bigger than 22 x 22 cm. This must be worked white on white as part of the challenge of whitework is to keep it white and fresh. The design should be appropriate for the techniques allowing areas large enough to achieve an effective amount of the pattern and be in proportion to the design. Stitches that must be included: PULLED THREAD WORK DRAWN THREAD WORK The work should include a minimum of five Hem stitch stitches showing a variety of textures. One or more Knotted variations Areas should be outlined with a suitable One or more Twisted variations surface stitch. Extra surface stitches can Needleweaving be used if they are appropriate and Corner decoration enhance the design; these must be in A choice of stabilising stitches over proportion to the design. -

Royal Show Needlework

Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 Volume 6 Number 8 1965 Article 9 1-1-1965 Royal Show needlework O Evans Scott Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4 Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Leisure Studies Commons Recommended Citation Evans Scott, O (1965) "Royal Show needlework," Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4: Vol. 6 : No. 8 , Article 9. Available at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4/vol6/iss8/9 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROYAL SHOW NEEDLEWORK By O. EVANS SCOTT WOMEN are stealing the "man" out of craftsmanship. Some of the best craftsmanship in this highly mechanised age is the work of women who can feel proud that their creative skill with the needle continues while factory production has largely replaced the craftsmanship once devoted to timber, leather and metal. There is deep satisfaction in creating previously in that show is eligible again an original piece of work in any material before entering something you entered and the fine needlework displayed at the last year. Royal and country shows merits the admiration it draws. Presentation of Work It also deserves greater attention to Work should be clean. It is an insult preparation and presentation than is to the judges and the show society to given in some cases.