Whitework Embroidery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VASTRAM: SPLENDID WORLD of INDIAN TEXTILES CURATED by SHELLY JYOTI a Traveling Textile Exhibition of Indian Council of Cultural Relations, New Delhi, India

VASTRAM: SPLENDID WORLD OF INDIAN TEXTILES CURATED BY SHELLY JYOTI A traveling textile exhibition of Indian council of Cultural Relations, New Delhi, India Curator : Shelly Jyo/ OPENING PREVIEW OCTOBER 15, 2015 DATES: UNTIL OCTOBER 2015 VENUE: PROMENANDE GARDEN, MUSCAT, OMAN ‘Textiles were a principal commodity in the trade of t i‘TexGles were a principal commodity in the trade of the pre-industrial age and India’s were in demand from china and Mediterranean. Indian coUons were prized for their fineness in weave, brilliance in colour, rich variety in designs and a dyeing technology which achieved a fastness of colour unrivalled in the world’ ‘Woven cargoes-Indian tex3les in the East’ by John Guy al age and India’s were in demand from china and Mediterranean. Indian cottons were prized for their fineness in weave, brilliance in colour, rich variety in designs and a dyeing technology which achieved a fastness of colour unrivalled in the world’ ‘Woven cargoes-Indian textiles in the East’ A traveling texGle exhibiGon of Indian council of Cultural Relaons, New Delhi, by John Guy India PICTORIAL CARPET Medium: Silk Dimension: 130cm x 79cm Source: Kashmir, India Classificaon: woven, Rug Accession No:7.1/MGC(I)/13 A traveling texGle exhibiGon of Indian council of Cultural Relaons, New Delhi, India PICTORIAL CARPET Medium: Silk Dimension: 130cm x 79cm Source: Kashmir, India Classificaon: woven, Rug Accession No:7.1/MGC(I)/13 Silk hand knoUed carpet depicts the Persian style hunGng scenes all over the field as well as on borders. Lots of human and animal figures in full moGons is the popular paern oaen seen in painGngs during the Mughal period. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

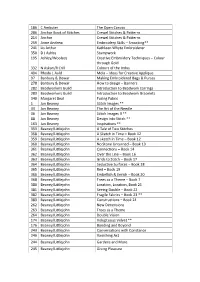

186 C Ambuter the Open Canvas 286 Anchor

186 C Ambuter The Open Canvas 286 Anchor Book of Stitches Crewel Stitches & Patterns 214 Anchor Crewel Stitches & Patterns 259 Anne Andrew Embroidery Skills – Smocking** 241 Lis Arthur Kathleen Whyte Embroiderer 350 D J Ashby Stumpwork 195 Ashley/Woolsey Creative Embroidery Techniques – Colour through Gold 332 N Askari/R Crill Colours of the Indus 404 Rhoda L Auld Mola – Ideas for Creative Applique 97 Banbury & Dewar Making Embroidered Bags & Purses 278 Banbury & Dewar How to design – Banners 282 Beadworkers Guild Introduction to Beadwork Earrings 283 Beadworkers Guild Introduction to Beadwork Bracelets 340 Margaret Beal Fusing Fabric 1 Jan Beaney Stitch Images ** 33 Jan Beaney The Art of the Needle 36 Jan Beaney Stitch Images II ** 88 Jan Beaney Design into Stitch ** 163 Jan Beaney Inspirations ** 353 Beaney/Littlejohn A Tale of Two Stitches 358 Beaney/Littlejohn A Sketch in Time – Book 12 359 Beaney/Littlejohn A sketch in Time – Book 12 360 Beaney/Littlejohn No Stone Unturned – Book 13 361 Beaney/Littlejohn Connections – Book 14 362 Beaney/Littlejohn Over the Line – Book 16 363 Beaney/Littlejohn Grids to Stitch – Book 17 364 Beaney/Littlejohn Seductive Surfaces – Book 18 365 Beaney/Littlejohn Red – Book 19 366 Beaney/Littlejohn Embellish & Enrich – Book 20 368 Beaney/Littlejohn Trees as a Theme – Book 7 380 Beaney/Littlejohn Location, Location, Book 21 381 Beaney/Littlejohn Seeing Double – Book 22 382 Beaney/Littlejohn Fragile Fabrics – Book 23 ** 383 Beaney/Littlejohn Constructions – Book 24 262 Beaney/Littlejohn New Dimensions 263 -

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni I’m including in this handout a couple of different ways of explaining “how-to” in blackwork, because not every explanation works for every person. Also, please excuse the crass commercial plugs. I didn’t have time to completely re-write, so pretend that this somebody else’s. Which it is! Anja and MaryAnne are not the same person. <grin> MaryAnne Bartlett is a 21st century woman, making a living by writing and researching, designing and selling blackwork designs and products. Anja Snihova’ was born in the late 14th century and due to the potions that her alchemist husband makes, survived into the early 17th century! Beginning Blackwork Blackwork is a counted thread technique made popular in England in the 1500's by Catharine of Aragon, the Spanish first wife of King Henry VIII of England. It was immortalized in the incredibly detailed portraits done by the court painter, Hans Holbein, whose name is give to the stitch used, which is just a running stitch that doubles back on itself at the other end of its "journey". Blackwork can be anything from a simple line drawing to the complex pattern of #10 below, and on to designs so complex no one seems to know how to do them! It was usually done with silk thread on a white even-weave linen, and despite the name of the technique, was done in every colour of the rainbow, although black was the most popular colour, followed by red and blue. The most peculiar thing about this technique is that, done properly, the design repeats on both the right and wrong sides of the fabric, making it perfect for collars, cuffs, veils and ribbons where both sides need to look nice! Blackwork Embroidery Instructions 1. -

Medieval Clothing and Textiles

Medieval Clothing & Textiles 2 Robin Netherton Gale R. Owen-Crocker Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 Medieval Clothing and Textiles ISSN 1744–5787 General Editors Robin Netherton St. Louis, Missouri, USA Gale R. Owen-Crocker University of Manchester, England Editorial Board Miranda Howard Haddock Western Michigan University, USA John Hines Cardiff University, Wales Kay Lacey Swindon, England John H. Munro University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada M. A. Nordtorp-Madson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA Frances Pritchard Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Monica L. Wright Middle Tennessee State University, USA Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 edited by ROBIN NETHERTON GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2006 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2006 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 1 84383 203 8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Illustrations page vii Tables ix Contributors xi Preface xiii 1 Dress and Accessories in the Early Irish Tale “The Wooing Of 1 Becfhola” Niamh Whitfield 2 The Embroidered Word: Text in the Bayeux Tapestry 35 Gale R. -

Madeira Embroidery

Blackwork Journey Inspirations Madeira Embroidery Madeira is an island located in the Atlantic Ocean west and slightly south of Portugal. The capital of Madeira is Funchai on the main island’s south coast and it was to Funchai, the capital that I travelled to explore the history of Madeira embroidery and find some modern examples of this traditional form of whitework embroidery. The hand embroidery of Madeira is generally recognised as being the finest of its kind available in the world. Over the last 150 years, Madeira has collected expertise from the fast disappearing regional centres of hand embroidery across Europe and moulded these various styles into a distinctive form of handwork recognised throughout the world. The Development of Madeira Embroidery The story began in the 1860’s when a wine shipper’s daughter, Elizabeth Phelps turned the rural pastime of simple embroidery into a cottage industry using her skills to motivate, organise and sell the work of the embroiders to Victorian England. In the 1860’s it was estimated that there were 70,000 women embroiderers (bordadeiras) in Madeira working on linen, silk, organdy and cotton to create table linen, clothing, bedding and handkerchiefs. Today there are about 30 companies producing handmade embroideries employing around 4,500 embroiderers. During the 19th century the main exports were to England and Germany. In the 20th century Madeiran Embroidery was exported to many parts of the world. Italy, the United States, South America and Australia became important markets. France, Singapore, Holland, Brazil and other countries also contributed to the trading expansion of and reputation of Madeira Embroidery. -

Editorial Calendar 2020

PRESERVING THE LEGACY OF NEEDLEWORK Editorial Calendar 2020 There are stories to be told, and PieceWork readers want to read them. Whether it’s a personal account of a master knitter (“Bertha Mae Shipley: A Navajo Knitter”) or a well-researched article on the embroidery that adorned alms purses (“Charitably Chic: The Eighteenth-Century Alms Purse”), PieceWork is the place to share these stories. People who care about handwork and who value its past and present role in the ongoing human story are PieceWork magazine’s core audience. PieceWork explores the personal stories of traditional makers and what they made and investigates how specific objects were crafted and the stories behind them. In-depth how-to techniques and step-by-step projects make the traditions come alive for today’s knitters, embroiderers, lacemakers, and crocheters. Beginning with the magazine’s inception in 1993, we have explored numerous needlework traditions and needleworkers. We’ve covered the prosaic—mending samplers—and the esoteric—the Pearly Kings and Queens of London. The stories have been poignant—the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire; inspiring—Safe Return Mittens; and entertaining—Rattlesnake Kate. Beginning with the Fall 2018 issue, PieceWork changed frequency from a bimonthly publication to a quarterly. The biggest bonus with this change was the addition of more editorial pages, allowing us to continue and expand upon PieceWork’s unusual blend of the elements behind a handwork tradition—who did it, how it was done, and why. Future issues will include core sections for techniques, including knitting, lace, embroidery, and crochet. Beyond these sections, there will be a wide variety of other needlework techniques. -

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016 GREEN text indicates an item in one of the Small Books boxes ORANGE text indicates a missing book PURPLE text indicates an oversize book BANNERS and CHURCH EMBROIDERY Aber, Ita THE ART OF JUDIAC NEEDLEWORK Scribners 1979 Banbury & Dewer How to design and make CHURCH KNEELERS ASN Publishing 1987 Beese, Pat EMBROIDERY FOR THE CHURCH Branford 1975 Blair, M & Ryan, Cathleen BANNERS AND FLAGS Harcourt, Brace 1977 Bradfield,Helen; Prigle,Joan & Ridout THE ART OF THE SPIRIT 1992 CEG CHURCH NEEDLEWORK EmbroiderersGuild1975T Christ Church Cathedral IN HIS HOUSE - THE STORY OF THE NEEDLEPOINT Christ Church Cathedral KNEELERS Dean, Beryl EMBROIDERY IN RELIGION AND CEREMONIAL Batsford 1981 Exeter Cathedra THE EXETER RONDELS Penwell Print 1989 Hall, Dorothea CHURCH EMBROIDERY Lyric Books Ltd 1983 Ingram, Elizabeth ed. THREAD OF GOLD (York Minster) Pitken 1987 King, Bucky & Martin, Jude ECCLESSIASTICAL CRAFTS VanNostrand 1978 Liddell, Jill THE PATCHWORK PILGRIMAGE VikingStudioBooks1993 Lugg, Vicky & Willcocks, John HERALDRY FOR EMBROIDERERS Batsford 1990 McNeil, Lucy & Johnson, Margaret CHURCH NEEDLEWORK, SANCTUARY LINENS Roth, Ann NEEDLEPOINT DESIGNS FROM THE MOSAICS OF Scribners 1975 RAVENNA Wolfe, Betty THE BANNER BOOK Moorhouse-Barlow 1974 CANVASWORK and BARGELLO Alford, Jane BEGINNERS GUIDE TO BERLINWORK Awege, Gayna KELIM CANVASWORK Search 1988 T Baker, Muriel: Eyre, Barbara: Wall, Margaret & NEEDLEPOINT: DESIGN YOUR OWN Scribners 1974 Westerfield, Charlotte Bucilla CANVAS EMBROIDERY STITCHES Bucilla T. Fasset, Kaffe GLORIOUS NEEDLEPOINT Century 1987 Feisner,Edith NEEDLEPOINT AND BEYOND Scribners 1980 Felcher, Cecelia THE NEEDLEPOINT WORK BOOK OF TRADITIONAL Prentice-Hall 1979 DESIGNS Field, Peggy & Linsley, June CANVAS EMBROIDERY Midhurst,London 1990 Fischer,P.& Lasker,A. -

Midlands Arts and Culture Magazine Spring-Summer 2017

Midlands andCulture ArtsMagazine A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH SPRING/SUMMER 2017 • ISSUE 27 THE WRITTEN WORD MUSIC & DANCE THEATRE & FILM VISUAL ARTS FREE MidlandsArts andCultureMagazine A Word from the Editor . .Page 2 National Drawing Day in Laois Poems from the School Room . .Page 3 NATIONAL Lighthouse Studios • Edgeworthstown . .Page 4 30 Artists/Anniversary . .Page 5 DRAWING Tullamore Club Sessions Poetry & Prose in Longford • Lars Vincent . .Page 6 DAY IN Yarnbombing Mountmellick . .Page 7 A Word from Offaly: Destination Festival . .Page 8 Longford ETB Film Course LAOIS the Editor Raised Bogs . .Page 9 National Drawing Day is a national Building creative communities is the event celebrating drawing in all its Dominic Reddin • Sean Rooney . .Page 10 ambition of the Creative Ireland forms and media. Laois Arthouse, Programme, a five year initiative which Westmeath Arts Grants . .Page 11 will run from 2017 to 2022. Kubrick by Candlelight . in conjunction with studio resident Longford Photographers . .Page 12 Saidhbhín Gibson, will host a The programme follows in the wake of the very successful Centenary comme- Dolores Keavney . .Page 13 workshop to encourage you to try out drawing. morations which saw a wide range of Kiki Theatre Grows • Fleadh in Ballymahon . .Page 14 arts, culture and heritage initiatives A Glimmer of an Idea . .Page 15 Join us for a fun workshop where you across the country. Alan Meredith • Aimee MacManus . .Page 16 will learn about drawing on Saturday 20 May from 11am to 1pm at Laois In the midlands there was an impressive Expressions • Singfest 2017 . .Page 17 Arthouse, Stradbally, Co Laois. -

Remembering Ricamo Italian Embroidery

GALLERY76 EXHIBITION GUIDE AN EXHIBITION OVERVIEW CURATOR: APRIL SPIERS AUGUST 2020 WATCH THE LIVE WALKTHROUGH AND CONVERSATION WITH FIBER TALK VIA https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=KF6Gc8AF9VE&feature=youtu.be RETICELLO Reticello (Italian, “small net”) is a variety of needle lace which arose in the 15th century, first recorded in Milan 1493, and remained popular into the 17th century. Reticello was originally a form of cutwork (where threads are pulled from linen fabric to form a grid on which the pattern is stitched primarily using buttonhole stitch) Later reticello used a grid made of thread rather than a fabric ground. Reticello is characterised by a geometric design of squares and circles and geometric motifs and is traditionally worked on white or ecru fabric. It is regarded as a forerunner of punto in aria. One of the contemporary champions of the style is Giuliana Buonpadre who established an Embroidery School in Verona in order to preserve the knowledge and skills involved in traditional Italian embroidery. Under her Karen Little guidance, Giuliana’s students have taken these traditional Reticello techniques and introduced a contemporary twist with the introduction of coloured threads. We have a number of these coloured pieces worked by Guild member Karen Little, along with a number of traditional pieces in this exhibition. Also known as: Greek point; reticello; point coupé; point couppe; radexela; radicelle Tina Miletta PUNTO ANTICO Punto Antico (Italian, “Antique Stitch) dates as far back as the 15th century and was known by a variety of names including Punto Toscano, Punto Reale, and Punto Riccio. The style did not became known as “Punto Antico” until the early 20th century. -

Textile Glossary Astrakhan Fabric: Knitted Or Woven

Textile Glossary Astrakhan fabric: knitted or woven fabric that imitates the looped surface of newborn karakul lambs Armscye: armhole Batiste: the softest of the lightweight opaque fabrics. It is made of cotton, wool, polyester, or a blend. Bertha collar: A wide, flat, round collar, often of lace or sheer fabric, worn with a low neckline in the Victorian era and resurrected in the 1940s Bishop sleeves: A long sleeve, fuller at the bottom than the top, and gathered into a cuff Box pleats: back-to-back knife pleats Brocade: richly decorative woven fabric often made with colored silk Broken twill weave: the diagonal weave of the twill is intentionally reversed at every two warp ends to form a random design Buckram: stiff loosely woven fabric Cambric: a fine thin white linen fabric Cap sleeves: A very short sleeve covering only the shoulder, not extending below armpit level. Cartridge pleat: formed by evenly gathering fabric using two or more lengths of basting stitches, and the top of each pleat is whipstitched onto the waistband or armscye. Chambray fabric: a lightweight clothing fabric with colored (often light blue) warp and white weft yarns Changeable fabric: warp and weft are different colors, when viewed from different angles looks more one color than the other Chemisette: an article of women's clothing worn to fill in the front and neckline of any garment Chiffon: lightweight, balanced plain-woven sheer fabric woven of alternate S- and Ztwist crepe (high-twist) yarns producing fabric with a little stretch and slightly rough texture -

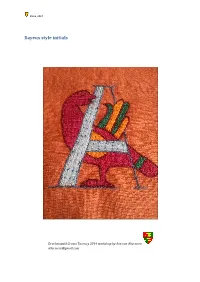

Bayeux Style Initials

©Ava, 2014 Bayeux style initials Drachenwald Crown Tourney 2014 workshop by Ava van Allecmere [email protected] Introduction: The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cloth—not an actual tapestry—nearly 70 metres (230 ft) long, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England concerning William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold, Earl of Wessex, later King of England, and culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The word tapestry comes from French tapisser, which means ‘to cover the wall’, thus wall covering. The tapestry consists of some fifty scenes with Latin tituli (captions), embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns. It is likely that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, William's half- brother, and made in England—not Bayeux—in the 1070s. In 1729 the hanging was rediscovered by scholars at a time when it was being displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral. The tapestry is now exhibited at Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy, France. In a series of pictures supported by a written commentary the tapestry tells the story of the events of 1064–1066 culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The two main protagonists are Harold Godwinson, recently crowned King of England, leading the Anglo-Saxon English, and William, Duke of Normandy, leading a mainly Norman army, sometimes called the companions of William the Conqueror. Construction, design and technique: The Bayeux tapestry is embroidered in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground 68.38 metres long and 0.5 metres wide (224.3 ft × 1.6 ft) and using two methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures.