Porphyria's Lover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meridian 599Brahms Primrose Inlay

Page 1 Johannes Brahms Gabriel Fauré Piano Quartet Piano Quartet G minor, op.25 C minor, op.15 The Primrose Piano Quartet Recorded using an historic Blüthner piano chosen by Brahms Page 2 Page 3 Gabriel Fauré: Piano Quartet C minor, op.15 dissonances (Fauré was Ravel's composition teacher). The slow movement is elegiac, tragic, and never self- association with the pathos of G minor, not least in his On hearing it for the first time, almost everyone is Stephen Johnson writes of Fauré's "intensity of feeling indulgent. The music moves magically from its own Piano Quartet and in the formal complexities of bowled over by the emotional exuberance and sheer balanced by elegance and formal lucidity". Fauré opening sombreness to a passage dreaming of happier its first movement, that one thinks of as the piano brilliance of Fauré's first Piano Quartet. It is one of himself wrote that "to express what is within you with times. This movement must surely reflect the unfolds the opening unison theme. Just a few bars later those pieces that music lovers can easily miss, for sincerity, in the clearest, most perfect manner, would emotionally traumatic time Fauré was experiencing comes the relative major, with a series of aside from the Requiem, one or two incidental pieces seem to me the ultimate goal of art". Mozart might during the period of its composition. His fiancé, appoggiaturas in sixths alternating between the piano such as Après un Rêve, and the Dolly Suite, Fauré's have said the same. The authors of the Record Guide in Marianne Viardot, with whom he was passionately in and upper strings (Specht imagines tender wooing). -

The Heavens and the Heart James Francis Brown

THE HEAVENS AND THE HEART CHORAL AND ORCHESTRAL MUSIC BY JAMES FRANCIS BROWN BENJAMIN NABARRO VIOLIN RACHEL ROBERTS VIOLA GEMMA ROSEFIELD CELLO CATRIONA SCOTT CLARINET THE CHOIR OF ROYAL HOLLOWAY ORCHESTRA NOVA GEORGE VASS CONDUCTOR The Heavens and the Heart Choral and Orchestral Music by James Francis Brown (b. 1969) Benjamin Nabarro violin 1. Trio Concertante [20:46] Rachel Roberts viola for violin, viola, cello and string orchestra Gemma Rosefield cello Clarinet Concerto Catriona Sco clarinet (Lost Lanes – Shadow Groves) The Choir of Royal Holloway for clarinet and string orchestra Orchestra Nova 2. Broad Sky – Interlude I [7:03] 3. Dark Lane – Interlude II [5:28] George Vass conductor 4. Around the Church – Interlude III [5:52] 5. The Far Grove [5:20] The Heavens and the Heart Three Psalms for chorus and small orchestra 6. Caeli enarrant gloriam Dei (Psalm 19) [6:05] 7. Si vere utique justitiam loquimini (Psalm 58) [6:48] 8. Bonum est confiteri Domino (Psalm 92) [6:40] Total playing time [64:07] About Orchestra Nova & George Vass: ‘Playing and recorded sound are both excellent. It’s a fascinating achievement, beautifully done’ Gramophone ‘[...] an outstanding recording of a powerful and absorbing work’ MusicWeb International James Francis Brown has been a close friend the age.’ The music on this recording for over twenty years. I first heard his music abundantly proves the connuing when, as Arsc Director of the Deal Fesval, truth of Tippe’s words from eighty I programmed his String Trio in 1996 and years ago. immediately recognised in him a kindred spirit. James is commied to the renewal David Mahews of tonality, but not the simplisc sort one finds in minimalism, rather one that uses real voice leading, modulaon and lyrical The Heavens and the Heart: Orchestral melody. -

Guild Music Limited Guild Catalogue 36 Central Avenue, West Molesey, Surrey, KT8 2QZ, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 8404 8307 Email: [email protected]

Guild Music Limited Guild Catalogue 36 Central Avenue, West Molesey, Surrey, KT8 2QZ, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 8404 8307 email: [email protected] CD-No. Title Composer/Track Artists GMCD 7101 Canticum Novum My soul, there is a country - Charles H.H.Parry; All Wisdom cometh from the Lord - Philip The Girl Choristers, The Boy Choristers and The Lay Vicars of Moore; Tomorrow shall be my dancing day - John Gardner; Psalm Prelude (2nd Set, No.1) - Salisbury Cathedral directed by Richard Seal / David Halls Organ / Herbert Howells; Quem vidistis pastores dicite - Francis Poulenc; Videntes stellam - Francis Martin Ings Trumpet Poulenc; The old order changeth - Richard Shepard; Even such is time - Robert Chilcott; Paean - Kenneth Leighton; When I survey the wondrous Cross - Malcolm Archer; Magnificat (Salisbury Service) - Richard Lloyd; A Hymn to the Virgin - Benjamin Britten; Pastorale - Percy Whitlock; Psalm 23 (Chant) - Henry Walford Davies; Love's endeavour, love's expense - Barry Rose; Ye Choirs of new Jerusalem - Richard Shepard GMCD 7102 Coronation Anthems & Hymns “Jubilant” Fanfare - Arthur Bliss; I was glad when they said unto me - Charles H.H. Parry; O The Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral directed by Barry Rose / Christopher taste and see - Ralph Vaughan Williams; Credo from the “Mass in G minor” - Ralph Vaughan Dearnley Organ Williams; Praise, my soul, the King of heaven - John Goss; Trumpet Tune f GMCD 7103 In Dulci Jubilo Ad Libitum/O Come, all ye faithful - Hark! the Herald-Angels Sing - Once in Royal David's city - - Festive & Christmas Music - Paul Plunkett Trumpets & Rudolf Lutz The First Nowell - Ding Dong! Merrily on High - Away in a Manger - Angels from the Realms Organ of Glory - Noël Op. -

Concert Diary October 2018

CONCERT DIARY 2018 – 2019 SUndayS at 6:30PM ‘Hear claSSical MUSic in A cool VenUE’ Time Out Red Priest Bringing the very best in classical chamber music to London audiences LONDON CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY AT KINGS PLACE The 2018/19 season of the London Chamber Piano trios appearing include the Rosamunde, Music Society’s concerts presents another Aquinas and Rautio, while the period piano fine array of chamber music of all types. trio Trio Goya opening our season with one The Chilingirian Quartet with violist Prunella of our ‘Up-Close’ concerts in the intimate Pacey continue their cycle of Mozart’s setting of Hall Two. Baroque music is featured astonishing six string quintets, and we have by our inimitable cover stars Red Priest and further concerts in our association with the also with a concert of concertos in April’s Albion Quartet, including a concert exploring Bach Weekend. We host the Italian pianist the theme of ‘counterpoint’, and culminating Alessandro Vena, the choir Sonoro, and the in a performance of Walton’s String Quartet. London Conchord Ensemble with a concert Other quartets appearing in the series include of beautiful music for wind and piano. the Brodsky, Dante, Allegri and Consone – In addition to our Kings Place programme, the latter joined by soprano Gillian Keith in a and as a new initiative, we have two concerts fascinating exploration of the relationship in collaboration with the Royal Over-Seas between the string quartet and Lieder. League in Piccadilly. There will be much to enjoy, and I look forward to seeing you in our One of our themes from January is Venus exciting new season. -

Concert Series at Vinehall

Welcome to International Classical GOLDNER STRING QUARTET ENGLISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VINEHALL INTERNATIONAL CONCERTS BOOKING FORM PIERS LANE (Piano) WIND ENSEMBLE Please complete as required. Bookings can be made by post, phone or Concerts at Vinehall email during the season. The Vinehall Concert Series, now in its 30th year, continues Saturday December 1st 2018 at 7.30 p.m. Sunday February 3rd 2019 at 3.00 p.m. to bring the best of both British and international musicians Sponsored anonymously A FULL SEASON TICKET provides one seat at each of the seven to East Sussex. Performances take place in a purpose-built concerts. The SIX CONCERT OPTION and the FIVE CONCERT 250 seat theatre with superb piano and intimate acoustic OPTION allow you to select six or five different concerts of your which is ideal for chamber music. choice. SINGLE TICKETS may also be booked for all concerts. MARTIN ROSCOE (Pno) CALLUM SMART (Vln) Please indicate your choice on the form overleaf. Complimentary LARA MELDA ALLEGRI STRING QUARTET refreshments are served at each concert. Saturday October 13th 2018 at 7.30 p.m. Saturday November 10th 2018 at 7.30 p.m. We regret that we cannot exchange or refund tickets unless a Sponsored by Paul and Margie Redstone in memory Sponsored anonymonsly concert is sold out. As concerts are booked many months on of Elsie Redstone “...the sincerity of Smart’s singing line is cause for celebration, and the recital is “One only had to hear the opening bars to realise advance there may be changes in advertised details. We are able to quite outstanding in its unique sequence and profile of a superb young player” this is a very fine quartet indeed.” The Telegraph offer assistance with transport throughout the area and have easy Andrew Parker, International Record Review “No praise could be high enough for Piers Lane whose playing throughout is access/parking for the disabled. -

Summer 2019 Events

SUMMER 2019 EVENTS WELCOME It is my pleasure as Director of Music to introduce this Events Guide for my first Summer Term at Purcell. I always enjoy building any artistic programme, and I hope that there is something here for everyone. We very much look forward to seeing you at any of the concerts and masterclasses in the booklet, either at school or in one of our prestigious London venues, including the Southbank Centre and Wigmore Hall. In a particularly exciting new venture, we shall be live streaming a series of concerts online, bringing The Purcell School Recital Room to you; enabling you to attend virtually, from wherever you are in the world. One of the joys of this place is the enormous range of work that happens every week, even in a term heavy with public exams. You will find every department of the school represented here, contributing to a rich menu of jazz, classical, romantic and 20th Century repertoire, alongside work by some of our many student composers. Solo recitals appear side by side with chamber ensembles, orchestras, choirs and many jazz ensembles. You will also see that we draw not only on the talents of our exceptional students: we also showcase some of our alumni, teaching staff, and world-renowned guest artists. I am looking forward to working with Stephen Isserlis at the Deal Festival in what will be my first public performance here as a conductor. I am also excited about the visits of Cambridge Professor John Rink and LSO oboist Juliana Koch. New collaborations this term include the Hertfordshire Festival of Music, and we continue to welcome longstanding friends such as Guy Johnston and Remus Azoitei. -

The Moving Finger Writes

GUILD MUSIC GMCD 7381 Fribbins – The Moving Finger Writes GMCD 7381 2012 Guild GmbH © 2012 Guild GmbH PETER FRIBBINS Guild GmbH Switzerland GUILD MUSIC GMCD 7381 Fribbins – The Moving Finger Writes A GUILD DIGITAL RECORDING • Recording Producers: Michael Ponder [1-4, 5, 9-10]; Tony Faulkner [6-8] PETER FRIBBINS (b. 1969) • Recording Engineers: Michael Ponder [1-4, 5, 9-10]; Tony Faulkner [6-8] • Recorded: St Silas Church, Chalk Farm, London, November 2010 [1-4]; Cadogan Hall, London, String Quartet No. 2 ‘After Cromer’ (2005-6) 9 April 2011 – ‘live’ recording of the premiere [6-8]; The Orangery, Trent Park, Middlesex University, 1 I. Presto. Allegro molto e drammatico 6:26 London, August 2011 [5, 9-10] 2 II. Andante 3:40 • Final master preparation: Reynolds Mastering, Colchester, England 3 III. Scherzo: Allegro giocoso 4:41 • Front cover picture: St Jerome writing (c. 1604) by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) 4 IV. Finale: Vivo 4:16 Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy / The Bridgeman Art Library – Chilingirian Quartet • Design: Paul Brooks, Design & Print – Oxford – Levon Chilingirian (violin), Ronald Birks (violin) Susie Mészáros (viola), Philip De Groote (cello) • Art direction: Guild GmbH • Executive co-ordination: Guild GmbH 5 A Haydn Prelude (2008) 2:46 – Anthony Hewitt (piano) • This recording was made with the kind support of Music Haven London and Middlesex University Piano Concerto (2010) 6 I. Adagio drammatico – Allegro vivo 12:14 7 II. Adagio – Andante – Tempo primo 10:11 8 III. Allegro vivo – Andante – Adagio – Affrettando – Fugato 8:20 – Diana Brekalo (piano) GUILD specialises in supreme recordings of the Great British Cathedral Choirs, Orchestral Works and exclusive Chamber Music. -

Classical Music Reviews & Magazine

Classical Music Reviews & Magazine - Fanfare Magazine - Angell Pn Tr: FRIBBINS Piano Trio. Stri... http://www.fanfaremag.com/content/view/42394/10246/ Home Departments Classical Reviews Our Advertisers About Fanfare Contact Us Advertise Here Next Issue Angell Pn Tr: FRIBBINS Piano Trio. String Quartet No. 1, Contents “I Have... on GUILD Current Issue Contents Classical Reviews - Composers & Works Written by Barnaby Rayfield Thursday, 27 January 2011 FRIBBINS Piano Trio. String Quartet No. 1, “I Have the Serpent Brought.” Cello Sonata. Clarinet Quintet • Angell Pn Tr; Allegri Str Qrt; John York (pn); Raphael Wallfisch (vc) • GUILD GMCD7343 (70:03) What is it with William Blake paintings this month? This is the second album to have his elusive, allegorical work grace a cover, elsewhere giving a disc of John Plant’s vocal works some literary emphasis, and in the case here with Blake’s Eve and the Serpent , an allusion not to his own poetry, but Subscribers, confusingly to John Donne’s Twicknam Garden , a line of which supplies the Enter the subtitle to Peter Fribbins’s First String Quartet. Donne and Blake could hardly Fanfare Archive be bettered to convey high-minded Britishness to a listener new to Fribbins (of which I am one), but my main impression after listening to this immensely Subscribers, rewarding collection of chamber music is of a continental flavor, with overtones Renew Your not of Tippett or Elgar, but of Ravel, Debussy, and even Janáček. Subscription Online There is something especially French in tone about Fribbins’s piano trio. Marked drammatico , the first movement’s hushed, tense violin writing opens Subscribe to out quickly into a rhapsodic melody, punctuated by some very Ravelian piano Fanfare harmonies. -

LCMS Newsletter Issue 2 Autumn 2010

Visual Arts: Kings Place Gallery Chamber Music Notes In October 2008, Nico Widerberg’s inaugural exhibition at Kings Place Gallery was honoured with a visit by the Crown Prince of Support and Norway and on the same day his commissioned sculpture was THE LCMS unveiled by the King of Norway at our sister gallery in Newcastle . Sponsorship Other equally memorable exhibitions have included Albert The LCMS sponsorship scheme Irvin’s vibrant canvases; Francis at Kings Place is now well under Giacobetti’s striking but stark way, and a wide range of photographs of Francis Bacon ; possibilities is available, including and Ian McKeever’s monumental Temple Paintings . More recent sponsoring one work or a exhibitions include Ørnulf complete concert. ISSUE 2 AUTUMN 2010 Opdahl’s Mood Paintings of the There is also the opportunity to Newsletter North and Sophie Benson’s commission a new work , with the premiere Vanishing Points , both a sober to be given at one of our Sunday concerts. contrast to Frans Widerberg’s Early in the 2010 spring season the Allegri Welcome! After Eden exhibition of Quartet gave the first performance of This has been a most successful season so far paintings in blazing primary Thomas Hyde’s string quartet, colours. both artistically and administratively. I would like commissioned by the John S Cohen to thank our partners at Kings Place—the box - Jane Bown’s exhibition Foundation. Other generous supporters office staff, duty managers, stage managers, t n Exposures , organized in have included Susan and Walter Rudeloff, a n technical staff, admin staff and ushers, whose n collaboration with the currently trustees of the LCMS, at a concert a H contributions make the concerts run so smoothly. -

New Releasesreleases

NEWNEW RELEASESRELEASES I HAVE THE SERPENT BROUGHT - MUSIC BY PETER FRIBBINS THE ANGELL TRIO - FRANCES ANGELL (PIANO), JAN PETER SCHMOLCK (VIOLIN), RICHARD MAY (CELLO) THE ALLEGRI STRING QUARTET - DANIEL ROWLAND & RAFAEL TODES (VIOLINS), DOROTEA VOGEL (VIOLA), PAL BANDA (CELLO) RAPHAEL WALLFISCH (CELLO), JOHN YORK (PIANO) JAMES CAMPBELL (CLARINETS) & THE ALLEGRI STRING QUARTET - PETER CARTER & RAFAEL TODES (VIOLINS), DOROTEA VOGEL (VIOLA), PAL BANDA (CELLO) The dramatic, expressive and highly melodic chamber music of the British composer Peter Fribbins, performed here by some of England’s finest chamber ensembles. The disc takes its name from the title of Fribbins’s first String Quartet ‘I Have the Serpent Brought’ after lines from John Donne’s remarkable 17th-century poem ‘Twicknam Garden’ on which it’s based. In 2007 the UK newspaper The Independent said Fribbins was ‘...one of the outstanding composers of his generation.’ This is a CD for all devotees of good string chamber music in the mainstream European tradition. GMCD 7343 FOLLOWING ON - MUSIC FOR FLUTE, OBOE AND PIANO THE FIBONACCI SEQUENCE CHRISTOPHER O’NEAL (OBOE), KATHRON STURROCK (PIANO), ILEANA RUHEMANN (FLUTE) This CD combines the music of Francis Poulenc and Tim Ewers. Both composers share an interest in melodic line with Ewers continuing the Poulenc tradition in a more contemporary idiom. In the title track, Following On, Ewers takes a fragment of the Poulenc oboe sonata as his starting point, but develops it in a very different, but equally melodious manner. The playing, as always with the Fibs, is superb, the sumptuous tone colour of the winds supported by Kathron Sturrock’s detailed and supremely musical pianism. -

CONWAY HALL CONCERTS SUNDAY Patrons

BIOGRAPHY The Primrose Piano Quartet was formed in 2004 by pianist John Thwaites and 3 of the UK’s most renowned CONWAY chamber musicians (Lindsay, Sorrel, Edinburgh, Maggini Quartets). It is named after the great Scottish violist, William Primrose, who himself played in the Festival Piano Quartet. Alongside their performances of the HALL major repertoire, the Primrose Quartet have researched widely the forgotten legacy of 20th century English SUNDAY composers, and have revived a number of remarkable and unjustly neglected piano quartets. Their award- winning recordings feature works by Dunhill, Hurlstone, Quilter, Bax, Scott, Alwyn, Howells and Frank Bridge. CONCERTS Sir Peter Maxwell-Davies wrote his Piano Quartet for the Primrose in 2008; this twenty-minute piece premièred at the Cheltenham Festival has proved very appealing, and was recorded in 2009 for the Meridian label. In 2009 an exciting commission, born out of their strong Scottish connections and timed to celebrate Robert Burns’s 250th anniversary, was the “Burns Air Variations”. The Primrose invited a number of their composer Patrons - Stephen Hough, Laura Ponsonby AGSM, Prunella Scales friends to write a short variation each on Burns’ “By Yon Castle Wa”, and the resulting 30-minute work CBE, Roderick Swanston, Hiro Takenouchi and Timothy West CBE received premières in Tunbridge Wells, at the Sound Festival, and at Kings Place. Sally Beamish, John Casken, Artistic Director - Simon Callaghan Jacques Cohen, Peter Fribbins, Francis Pott, Zoë Martlew, Piers Hellawell and Stephen Goss are among those who contributed. Two new CDs were released during 2010 on the Meridian label: Richard Strauss Piano Quartet, Violin Sonata and Cello Sonata; Maxwell Davies’ Piano Quartet, the Burns Air Variations and a previously unrecorded Piano Quintet by Dmitri Smirnov. -

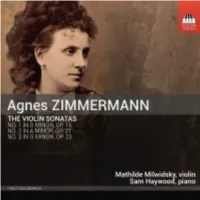

TOCC0541DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THE VIOLIN SONATAS OF AGNES ZIMMERMANN by Peter Fribbins To the majority of musicians and music-lovers of the present day the mention of Agnes Zimmermann would chiefly recall her well-known editions of the works of Mozart and Schumann and the Sonatas of Beethoven – classics to which she brought stores of accumulated knowledge and the most painstaking accuracy. In the musical world of the ’seventies, ’eighties, and ’nineties, Agnes Zimmermann occupied a central place among artists. She was a familiar figure […] both as soloist and in collaboration with those masters among instrumentalists, Joachim, Madame Norman-Neruda (Lady Halle), Ludwig Straus, Piatti, and others. In all the ‘musical matinees’ and fashionable concerts of those days Agnes Zimmermann took part. She also visited Leipsic, Hamburg, Berlin, Brussels, and Frankfurt, often in conjunction with Dr. Joachim. At the Halle concerts at Manchester, Agnes Zimmermann was a frequent and welcome visitor, and also at the great English provincial towns […].1 The story of this recording begins with my role as Artistic Director of the London Chamber Music Society concerts. These Sunday concerts have been presented at Kings Place, near King’s Cross Station, since 2008, but were hosted at the Conway Hall in Red Lion Square from 1929, and before that at South Place in the City of London, where, as the South Place Sunday Concerts, they had begun life in 1887. Their archives reveal a fascinating history over the years. On Sunday, 24 January 1915, for example, following the worst of the Suffragette-movement unrest through 1913 and 1914, there was a concert featuring music entirely by contemporary women composers, performed by notable female performers of the day.