State of Asian Elephant Conservation in 2003 I List of Boxes Box 1 the Scorecard System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Reindeer Grazing Permits on the Seward Peninsula

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Anchorage Field Office 4700 BLM Road Anchorage, Alaska 99507 http://www.blm.gov/ak/st/en/fo/ado.html Environmental Assessment: DOI-BLM-AK-010-2009-0007-EA Reindeer Grazing Permits on the Seward Peninsula Applicant: Clark Davis Case File No.: F-035186 Applicant: Fred Goodhope Case File No.: F-030183 Applicant: Thomas Gray Case File No.: FF-024210 Applicant: Nathan Hadley Case File No.: FF-085605 Applicant: Merlin Henry Case File No.: F-030387 Applicant: Harry Karmun Case File No. : F-030432 Applicant: Julia Lee Case File No.: F-030165 Applicant: Roger Menadelook Case File No.: FF-085288 Applicant: James Noyakuk Case File No.: FF-019442 Applicant: Leonard Olanna Case File No.: FF-011729 Applicant: Faye Ongtowasruk Case File No.: FF-000898 Applicant: Palmer Sagoonick Case File No.: FF-000839 Applicant: Douglas Sheldon Case File No.: FF-085604 Applicant: John A. Walker Case File No.: FF-087313 Applicant: Clifford Weyiouanna Case File No.: FF-011516 Location: Bureau of Land Management lands on the Seward Peninsula Prepared By: BLM, Anchorage Field Office, Resources Branch December 2008 DECISION RECORD and FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT I. Decision: It is my decision to issue ten-year grazing permits on Bureau of Land Management lands to reindeer herders on the Seward and Baldwin peninsulas, Alaska. The permits shall be subject to the terms and conditions set forth in Alternative B of the attached Reindeer Grazing Programmatic Environmental Assessment. II. Rationale for the Decision: The Reindeer Industry Act of 1937, 500 Stat. 900, authorizes the Secretary’s regulation of reindeer grazing on Federal public lands on the peninsulas. -

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China TRACEY L-D LU NEARL Y EIGHTY YEARS HAVE ELAPSED since Swedish scholar J. G. Andersson discovered a piece of rice husk on a Yangshao potsherd found in the middle Yel low River Valley in 1927 (Andersson 1929). Today, many scholars agree that China 1 is one of the centers for an indigenous origin of agriculture, with broom corn and foxtail millets and rice being the major domesticated crops (e.g., Craw-· ford 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Higham 1995; Smith 1995) and dog and pig as the primary animal domesticates (Yuan 2001). It is not clear whether chicken and water buffalo were also indigenously domesticated in China (Liu 2004; Yuan 2001). The origin of agriculture in China by no later than 9000 years ago is an impor tant issue in prehistoric archaeology. Agriculture is the foundation of Chinese civ ilization. Further, the expansion of agriculture in Asia might have related to the origin and dispersal of the Austronesian and Austroasiatic speakers (e.g., Bellwood 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Glover and Higham 1995; Tsang 2005). Thus the issue is essential for our understanding of Asian and Pacific prehistory and the origins of agriculture in the world. Many scholars have discussed various aspects regarding the origin of agriculture in China, particularly after the 1960s (e.g., Bellwood 1996, 2005; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Chen 1991; Chinese Academy of Agronomy 1986; Crawford 1992, 2005; Crawford and Shen 1998; Flannery 1973; Higham 1995; Higham and Lu 1998; Ho 1969; Li and Lu 1981; Lu 1998, 1999, 2001, 2002; MacN eish et al. -

Advanced Training Techniques for Oxen Techguide

Tillers‟ TechGuide Advanced Training Techniques for Oxen by Drew Conroy Assistant Professor, University of New Hampshire Copyright, 1995: Tillers International Chapter 1 Introduction Acknowledgements A team of well-trained oxen is a joy to watch and The author was inspired to write this TechGuide while to work. Even the most skilled cattlemen are teaching an “Oxen Basics” workshop at Tillers. Drew impressed with the responsiveness and spent evenings reviewing literature that Tillers has obedience that oxen demonstrate.under what I gathered from around the world on ox training. He was would consider ideal circumstances. I had no impressed that, despite minimal interaction and brief documentation, the training approaches from around the knowledge of training cattle, no written materials world were very similar. He decided to expand on training to fall back on, and only a basic understanding of techniques beyond what he had included in the Oxen cattle behavior. As a boy, I did have lots of time, Handbook and beyond our prior TechGuide on Training patience, and some guidance from experienced Young Steers. ox teamsters. We look forward to comments. Future revisions will Many years and many teams later, I can honestly integrate suggestions, corrections, and improvements to say those first oxen were also my best-trained illustrations. Please send comments to: Tillers th team. My success with that team was due International , 5239 South 24 Street, Kalamazoo, MI primarily to the cattle being very friendly, hand 49002 USA. fed since birth, and very young when I began Publishing of this revision was supported by the Roy and training. -

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima of the Future

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima © CopyrightAmerican Association o fBovine Practitioners; open access distribution. of the Future W. Ross Cockrill, D.V.M., F.R.C.V.S., Consultant, Animal Production, Protection & Health, Food and Agriculture Organization Rome, Italy Summary to produce the cattalo, or beefalo, a heavy meat- The water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) is a type animal for which widely publicized claims neglected bovine animal with a notable and so far have been made. The water buffalo has never been unexploited potential, especially for meat and shown to produce offspring either fertile or sterile milk production. World buffalo stocks, which at when mated with cattle, although under suitable present total 150 million in some 40 countries, are conditions a bull will serve female buffaloes, while increasing steadily. a male buffalo will mount cows. It is important that national stocks should be There are about 150 million water buffaloes in the upgraded by selective breeding allied to improved world compared to a cattle population of around 1,- management and nutrition but, from the stand 165 million. This is a significant figure, especially point of increased production and the full realiza when it is considered that the majority of buffaloes tion of potential, it is equally important that are productive in terms of milk, work and meat, or crossbreeding should be carried out extensively any two of these outputs, whereas a high proportion of especially in association with schemes to increase the world’s cattle is economically useless. and improve buffalo meat production. In the majority of buffalo-owning countries, and in Meat from buffaloes which are reared and fed all those in which buffaloes make an important con for early slaughter is of excellent quality. -

Introducing Agricultural Engineering in China Edwin L

Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Technical Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Reports and White Papers 6-1-1949 Introducing Agricultural Engineering in China Edwin L. Hansen Howard F. McColly Archie A. Stone J. Brownlee Davidson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/abe_eng_reports Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Edwin L.; McColly, Howard F.; Stone, Archie A.; and Davidson, J. Brownlee, "Introducing Agricultural Engineering in China" (1949). Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Technical Reports and White Papers. 14. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/abe_eng_reports/14 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Technical Reports and White Papers by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introducing Agricultural Engineering in China Abstract The ommittC ee on Agricultural Engineering in China. was invited by the Chinese government to visit the country and determine by research and demonstration the practicability of introducing agricultural engineering techniques, and to assist in advancing education in the field of agricultural engineering. The program of the Committee was carried out under the direction of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. The program was sponsored by the International Harvester Company of Chicago, assisted by twenty- four other American firms. Disciplines Agriculture | Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering This report is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/abe_eng_reports/14 Introducing AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING in China The Committee on Agricultural Engineering in China. -

General Guidelines on Ox Ploughing, Agric Marketing, Agro Dealership and Farmer Field School

Oxen Ploughing Guide | General Guidelines on Ox ploughing, Agric marketing, Agro dealership and Farmer Field School Foreword and Food Security, and the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries are mandated to ensure that the people of F Agriculture Livestock Extension Policy (NALEP) and launched the process of developing the Comprehensive Agriculture Master Plan (CAMP) through which many projects will be implemented. and livestock rearing that our smallholder farmers and families depend on is improved. community based extension workers at both county and payam levels. The process was rigorous. I am assured that the three guides (crops, livestock and the general guidelines) are country. I am delighted that these guides in the form of booklets will now be used across the country. Hon. Dr Lam Akol Ajawin Minister of Agriculture and Food Security The Republic of South Sudan 2 Preface T across Africa but most especially from the East African sub region. The European Union through the South Sudan Rural Development Programme (SORUDEV) funded and facilitated the process. states and was validated twice in the equatorial states of Yei and recently in Juba Juba in May 2016. Throughout and relevance were checked and improved on. namely Sorghum, Maize, Rice, Sesame, Cowpeas, Groundnut, Beans, Cassava, Sweet Potatoes, Tomatoes and ‘Tayo Alabi Facilitator 3 CONTE NTS Foreword 2 Preface 3 A Oxen Ploughing Introduction 5 Training Calendar 7 Parts of a yoke 9 Plough Techniques 10 Other Draughts Implements 11 B Agricultural Marketing Introduction 15 Marketing -

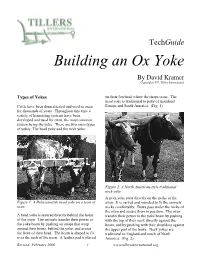

Building an Ox Yoke Techguide

TechGuide Building an Ox Yoke By David Kramer Copyright 1997, Tillers International Types of Yokes on their forehead where the straps cross. The head yoke is traditional to parts of mainland Cattle have been domesticated and used as oxen Europe and South America. (Fig. 1) for thousands of years. Throughout this time a variety of harnessing systems have been developed and used for oxen, the most common system being the yoke. There are two main types of yokes: The head yoke and the neck yoke. Figure 2: A North American-style traditional neck yoke. A neck yoke rests directly on the necks of the Figure 1: A Bolivian-style head yoke on a team of oxen. It is carved and rounded to fit the animals' oxen. necks comfortably. Bows pass under the necks of the oxen and secure them in position. The oxen A head yoke is secured directly behind the horns transfer their power to the yoke beam by pushing of the oxen. The animals transfer their power to with the top of their neck directly against the the yoke beam by pushing on straps that wrap beam, and by pushing with their shoulders against around their horns, behind the yoke, and across the upper part of the bows. Neck yokes are the front of their head. The beam is shaped to fit traditional to England and much of North over the neck of the oxen. A leather pad is placed America. (Fig. 2) Revised: February 2000 1 www.tillersinternational.org Figure 3: Parts of a traditional neck yoke: A – yoke beam; B – bows; C – bow width and size of yoke; D – spacer block; E – bow pin; F – staple; G – pole ring; H – chain hook. -

Bones of the Hindlimb

BONES OF THE HINDLIMB Andrea Heinzlmann University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest Department of Anatomy and Histology 1st Oktober 2019 BONES OF THE HINDLIMB COMPOSED OF: 1. PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) 2. THIGH 3. LEG (CRUS) 4. FOOT (PES) BONES OF THE PELVIC LIMB (OSSA MEMBRI PELVINI) PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI): - connection between the pelvic limb and the trunk consists of: 1. two HIP BONES (OSSA COXARUM) Hip bones of a pig, dorsal aspect Hip bones of a pig, ventral aspect PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) HIP BONE (OS COXAE): - in young animals each hip bone comprises three bones: 1. ILIUM (OS ILII) – craniodorsal 2. PUBIS (OS PUBIS) – cranioventral 3. ISHIUM (OS ISCHI) – caudoventral - all three bones united by a synchondrosis - the synchondrosis ossifies later in life Hip bones of an ox, left lateral aspect Hip bones of an ox, ventrocranial aspect PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) HIP BONE (OS COXAE): ACETABULUM: - ilium, pubis and ischium meet at the acetabulum Left acetabulum of a horse, lateral aspect Hip bones of a dog, right lateral aspect Left acetabulum of an ox, lateral aspect PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) HIP BONE (OS COXAE): SYMPHYSIS PELVINA: - the two hip bones united ventrally at the symphysis pelvina by a fibrocartilaginous joint ossified with advancing age - in females the fibrocartilage of the symphysis becomes loosened during pregnancy by action of hormones Hip bones of a horse, ventrocranial aspect Hip bones of an ox, ventrocranial aspect PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) HIP BONE (OS COXAE): SYMPHYSIS PELVINA: - in females the fibrocartilage of the symphysis becomes loosened during pregnancy by action of hormones http://pchorse.se/index.php/en/articles/topic-of-the-month/topics-topics/4395-mars2017-eng PELVIC GIRDLE (CINGULUM MEMBRI PELVINI) HIP BONE (OS COXAE): SYMPHYSIS PELVINA divided into: 1. -

A History of Animal Traction in Africa: Origins and Modern Trends

A history of animal traction in Africa: origins and modern trends Prepared for pre-circulation at a conference to be held in Kyoto University of African and Asian Studies, February 6-7th, 2015. [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT -NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR] Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0) 7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, January 1, 2015 Roger Blench Animal traction in Africa Circulated for comment TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS II 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. ORIGINS 1 3. ANIMAL TRACTION IN NORTH AFRICA 2 4. ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN OF AFRICA 3 5. ANIMAL POWER IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA 5 5.1 General 5 5.2 Ploughs 5 5.3 Carts 6 5.4 Sledges 6 6. STATIONARY APPLICATIONS OF ANIMAL POWER 7 7. COLONIAL PROMOTION OF ANIMAL TRACTION IN AGRICULTURE 9 8. POST-INDEPENDENCE PROMOTION OF ANIMAL TRACTION 11 9. ANIMAL TRACTION AND DEVELOPMENT PRACTICE 13 10. CURRENT SITUATION AND TRENDS 14 11. CONCLUSIONS 15 REFERENCES 16 TABLES Table 1. Species used for Animal Traction in Nigeria ............................................................................... 10 PHOTOS Photo 1. Egyptian ard........................................................................................................................................ 1 Photo 2. Wooden model of Ancient Egyptian plough...................................................................................... -

12 Yaks, Yak Dung, and Prehistoric Human Habitation of the Tibetan

12 Yaks, yak Dung, and prehistoric human habitation of the Tibetan Plateau David Rhode1,*, David B. Madsen2, P. Jeffrey Brantingham3 and Tsultrim Dargye4 1 Division of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences, Desert Research Institute, Reno, NV, USA 2 Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA 3 Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles 4 GTZ Qinghai New Energy Research Institute, Xining, Qinghai Province, P.R. China *Corresponding author: David Rhode, Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV 89512 USA; Tel: 775-673-7310; Fax: 775-673-7397, E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract human hair extenders). The yak’s fine wooly underfur is made into yarn, felt, clothing, and blankets. Yak leather This paper explores the importance of yak dung as a source goes into bags, belts, boots, bundles, binding, bridles, of fuel for early human inhabitants of the Tibetan Plateau. bellows, boat hulls, breastplates, and beyond. Pastoralists The wild and domestic yak is introduced, followed by a trade yaks and yak products with neighboring farmers, discussion of yak dung production, collection, and energetic merchants, and lamaseries for the essentials and luxuries return. Yak dung is compared with other products such as not available locally – tea and oil, barley and peas, spices milk, pack energy, and meat, demonstrating its high ener- and snuff, pots and pans, tea bowls and prayer wheels, tent getic value while emphasizing that various yak products poles and needles, silk brocade and silver plate, rifles and serve different, complementary, and nonfungible purposes. binoculars. In the spiritual realm, the yak is godly, its Following this review of yak dung energetics, issues related skulls and horns and butter fashioned into icons to be to the early peopling of the Tibetan Plateau become the revered. -

The Benefits of Integrating an Assistance Dog with Military Chaplain Corps Services at the 169Th Fighter Wing, Mcentire Joint National Guard Base, South Carolina

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University Doctor of Ministry Projects School of Divinity Spring 2021 The Benefits of Integrating an Assistance Dog with Military Chaplain Corps Services at the 169th Fighter Wing, McEntire Joint National Guard Base, South Carolina Christina Pittman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/divinity_etd Part of the Religion Commons Citation Information Pittman, Christina, "The Benefits of Integrating an Assistance Dog with Military Chaplain Corps Services at the 169th Fighter Wing, McEntire Joint National Guard Base, South Carolina" (2021). Doctor of Ministry Projects. 52. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/divinity_etd/52 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Divinity at Digital Commons @ Gardner- Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please see Copyright and Publishing Info. THE BENEFITS OF INTEGRATING AN ASSISTANCE DOG WITH MILITARY CHAPLAIN CORPS SERVICES AT THE 169th FIGHTER WING, MCENTIRE JOINT NATIONAL GUARD BASE, SOUTH CAROLINA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE M. CHRISTOPHER WHITE SCHOOL OF DIVINITY GARDNER-WEBB UNIVERSITY BOILING SPRINGS, NORTH CAROLINA IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY CHRISTINA PRYOR PITTMAN MAY 2021 APPROVAL FORM THE BENEFITS OF INTEGRATING AN ASSISTANCE DOG WITH MILITARY CHAPLAIN CORPS SERVICES AT THE 169th FIGHTER WING, MCENTIRE JOINT NATIONAL GUARD BASE, SOUTH CAROLINA CHRISTINA PRYOR PITTMAN Approved by: (Faculty Advisor) (Field Supervisor) (D.Min. Director) Date:_____________________ Copyright © 2021 by Christina Pryor Pittman All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My God who is relentless to keep chasing after me and lovingly redeems me.