Automotive Industry?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSUE 84 / 2020 Freetorial He Great Thing About Being Free Car Mag Is That We Are Just MG India Brand Ambassador That, Free

Get the Look Should you buy... Communist Chinese Cars? & from companies that work within the People's Republic? We try on some ultra cool T-Shirts with a distinctly Swedish theme which might be turbocharged... freecarmag.co.uk 1 ISSUE 84 / 2020 freetorial He great tHing about being Free Car Mag is tHat we are just MG India brand ambassador that, free. Free to write about what we please. Difcult things. T I was ratHer interested in wHat car manufacturers tHougHt Benedict Cumberbatch about operating in CHina. Sadly, in just about every instance, tHey Had notHing to sHare witH us, wHicH was a sHame. RigHt now cooperating witH a Communist political system would not seem to be tHe most etHical tHing to do. Indeed, unravelling tHemsleves from a globalised system tHat Has caused plenty of supply cHain issues recently would be tHe smart, business tHing to do. For tHe rest of us Bangernomics Mag (www.bangernomics.com) offers a positive way forward. Instead, car manufacturers prefer to stay away from tHe really important issues. THey could of course cHoose to be free. 4 News Events Celebs MeanwHile...say Hello to SHazHad SHeikH wHo Has been writing 8 China Crises about and driving all tHe exciting cars for decades as #browncarguy. See you next time. 10 Made in China 16 Mercedes World 18 Back Seat Driver 19 Future Proof Vauxhall Mokka 22 Saab Tees 23 Wanted Mr Jones Watch 24 Buy Now KIa, SEAT , Skoda 26 Alliance of British Drivers 28 The #Brown Car Guy Column 30 Next Time - BMW Isetta? James Ruppert The Brit Issue EDITOR [email protected] Cover Credits l Fiat • MG Motors India • Saab Tees THE TEAM Editor James Ruppert Publisher Dee Ruppert Backing MAG Sub Editor Marion King Product Tester Livy Ruppert Britain Photographer Andrew Elphick Our 5 point plan Web Design Chris Allen Columnist Shahzad Sheikh ©2020 Free Car Mag Limited is available worldwide Reporter Kiran Parmar witHout any restrictions. -

Autoconf18 Report EN.Pdf

8th Edition CPRJ Plastics in Automotive Conference & Showcase and 2018 Annual Conference of Society of Automotive Engineers of Chongqing 8-9.11.2018 | Venue: Radisson Blu Hotel Chongqing Shapingba Adsale Publishing Ltd. ( Adsale Group) Society of Automotive Engineers of Chongqing China Plastics & Rubber Journal CHINAPLAS Society Plastics Engineers (SPE) SpecialChem.com Guangzhou International Electric Vehicles Show 2018 Guangzhou International Auto Parts & Accessories Exhibition China Central and Western Regions Plastics Industry Alliance More Details:AdsaleCPRJ.com/AutoConference 1 / 20 8th Edition CPRJ Plastics in Automotive Conference & Showcase and 2018 Annual Conference of Society of Automotive Engineers of Chongqing Salute to the Following Sponsors 2 / 20 8th Edition CPRJ Plastics in Automotive Conference & Showcase and 2018 Annual Conference of Society of Automotive Engineers of Chongqing Conference Programme Morning Session 08:00-12:15 08:00 Audience Reception 08:40 Welcome Remarks Adsale Group, Adsale Publishing Ltd. General Manager, Janet Tong The Moderator: Society of Automotive Engineers of Chongqing, Vice President, Jianping Lou Prof. Yansong He 08:50 Yanfeng Plastic Omnium Automotive Exterior Systems Co., Ltd. - Wei Wang, Head of Smart Manufacturing The development of unmanned manufacturing for automotive exterior design 09:20 HuaChen Automotive Engineering Research Institute - Zhi li, Chief Engineer of Automotive Engineering Research Institute &Leader of Non-metal Material The applications and development roadmap of non-metal materials for light weighting of Brilliance Auto Group. 09:50 Jinyoung (Xiamen) Advanced Materials Technology Co., Ltd. - Steven Gao, Director of Vehicle Material, Jinyoung Advanced Materials Leading Solutions on New Energy Vehicle Application 10:10 Ningbo Shuangma Machinery Industry Co., Ltd. - Yupeng Liu, CTO Research and application of fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites molding technology 10:30 Coffee Break / Networking / Exhibition Visiting 11:00 Changan Ford Automobile Co., Ltd. -

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM Negotiable Commercial Paper Not

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM Negotiable commercial paper (Negotiable European Commercial Paper - NEU CP-)1 Not guaranteed programme Information Memorandum Name of the programme RENAULT NEU CP Name of the issuer RENAULT S.A. Type of programme NEU CP Programme size EUR 1,500,000,000 Guarantor(s) None Rating(s) of the programme Rated by Standard & Poors, Rated by Moody’s Arranger(s) None Issuing and paying agent(s) (IPA) RCI BANQUE Dealer(s) Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank, BNP Paribas, Natixis, Société Générale, Crédit Industriel et Commercial, HSBC France, Bred Banque Populaire, Aurel BGC, HPC, ING Bank France SA, Newedge group, Renault Finance, Crédit du Nord, Kepler Capital Markets SA, UBS, Tullet Prebon (Europe) Ltd, Tradition, Finarbit, GFI Securities Limited Date of the information memorandum [TBC] Update by amendment (if required) None Drawn up pursuant to articles L 213-1A to L 213-4-1 of the French monetary and financial code A copy of the information memorandum is sent to: BANQUE DE FRANCE Direction générale de la stabilité financière et des opérations (DGSO) Direction de la mise en œuvre de la politique monétaire (DMPM) 21-1134 Service des Titres de Créances Négociables (STCN) 39, rue Croix des Petits Champs 75049 PARIS CEDEX 01 Avertissement : cette documentation financière étant rédigée dans une langue usuelle en matière financière autre que le français, l’émetteur invite l’investisseur, le cas échéant, à recourir à une traduction en français de cette documentation. Translation : Warning : as this information memorandum is issued in a customary language in the financial sphere other than French, the issuer invites the investor, when appropriate, to resort to a French translation of this documentation. -

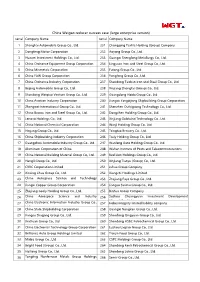

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

2020 International Forum (TEDA) on Chinese Automotive Industry

2020 International Forum (TEDA) on Chinese Automotive Industry Development Annual Theme: Double Upgrading of Industry and Consumption Restructuring the New Ecological Layout September 4, 2020 (Offline Meeting) Opening and Cooperation to achieve Win-win in Future: Development Environment for High-level Autonomous Driving and International Coordination Background: At present, the mass production of low-level autonomous driving vehicles has started. The development of high-level self-driving vehicles is still in the initial stage due to the impacts of various factors such as laws, regulations, usage environment, and technology maturity etc.. Europe, the United States, and other countries and regions have been relatively active in programming and investing in the field of autonomous driving. The R & D and tests on autonomous vehicles had been carried out earlier; the Framework Documents for Autonomous Driving Vehicles, which was jointly established by China, the European Union, Japan and the United States, had passed the examination of the United Nations in June 2019. It is a solid step in the development of high-level self-driving vehicles. However, G9 Forum (VIP the future development is still highly dependent on the supports of the policy Closed-door Meeting, environment, technology R&D, and the building of infrastructure. Therefore, to for VIP only) carry out international exchanges and cooperation to actively promote the development of autonomous driving and intelligent connection has become an 13:00~15:30 important direction for the sustainable development of the automotive industries in various countries. Form of Meeting: Build a multilateral communication platform for the automotive industry. The host will lead each speaker to gave a speech (about 5 minutes) in turn. -

China Zhengtong Auto Services Holdings Limited 中國正通汽車服務控股有限公司 (Established Under the Laws of the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (The “Company”)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission take no responsibility for the contents of this Web Proof Information Pack, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Web Proof Information Pack. Web Proof Information Pack of China ZhengTong Auto Services Holdings Limited 中國正通汽車服務控股有限公司 (established under the laws of the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (the “Company”) This Web Proof Information Pack (“WPIP”) is being published as required by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“HKEx”)/the Securities and Futures Commission solely for the purpose of providing information to the public in Hong Kong. This WPIP is in draft form. The information contained in it is incomplete and is subject to changes which could potentially be material. By viewing this document, you acknowledge, accept and agree with the Company, any of its affiliates, sponsors, advisers and members of the underwriting syndicate that: (a) this WPIP is only for the purpose of facilitating equal dissemination of information to investors in Hong Kong and not for any other purposes. No investment decision should be based on the information contained in this WPIP; (b) the posting of this WPIP or supplemental, revised or replacement pages on the HKEx Website does not give rise to any obligation of the Company, any of its affiliates, sponsors, advisers and/or members of the underwriting syndicate to proceed with an offering in Hong Kong or any other jurisdiction. -

DBS Group Research

China / Hong Kong Industry Flash Note Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 18 Apr 2018 China Auto Sector A N ALYST Rachel MIU +852 2863 8843 [email protected] Government to liberalise auto sector over next 5 years Foreign ownership limits on new energy vehicles to be removed in 2018, on commercial 2. The commercial vehicle market accounts for about 30% vehicles in 2020 and on passenger vehicles in of the total vehicle market in China. Chinese commercial 2022 vehicle manufacturers such as Sinotruk, Qingling Motors and Dongfeng Motor have collaborations with MAN, Isuzu, Most international automakers have JVs in and Volvo Commercial Vehicles, etc. China; expect Tesla to ride on this new policy State-owned auto enterprises derive most of 3. State-owned automotive enterprises have many joint their earnings from JVs ventures with Japanese, European, American and Korean automakers in the passenger vehicles segment, and rely on Foreign automakers to be allowed more than 2 these ventures for most of their earnings. SAIC Motor Corp JVs. We prefer dealers like Zhonsheng (881HK) has JVs with General Motors and Volkswagen; Dongfeng and ZhengTong (3668 HK) which are not Motor with Nissan, Honda, Renault, Peugeot Citroen and affected by the new policy. Among the Infiniti; Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group with Honda, automakers, GAC (2238 HK) has a relatively Toyota, Fiat Chrysler and Mitsubishi; Changan Automobile strong self brand to mitigate any potential Group with Ford, Suzuki and Peugeot Citroen; Beijing negative impact. Automotive Industry Holding Co with Daimler and Hyundai; Brilliance Auto Group with BMW and Renault. -

Ar 20 Eng.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Vision To build a first-class commercial bank among peers, with full functionality, diversified businesses and salient features Mission Serving customers Rewarding shareholders Fulfilling the value of employees Making contributions to the society Core values Faithfulness Responsibility Innovation Conscientiousness Introduction of the Bank Established in 1988, China Guangfa Bank is one of the earliest incorporated joint-stock commercial banks in China. The Bank upholds the core values of “faithfulness, responsibility, innovation and conscientiousness”, bears in mind the historic mission of “serving customers, rewarding shareholders, fulfilling the value of employees and making contributions to the society”, practices the service concept of “know each other for you” and strives towards its strategic vision of being “one of the first-class commercial banks in China”. The Bank aims to provide customers with high-quality, efficient and comprehensive financial services. The Bank’s network has expanded to include 46 Tier-1 branches and 882 business outlets in 104 cities at and above the prefecture level in 25 provinces (municipalities and autonomous regions) including Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Xinjiang and the Hong Kong and Macau Special Administrative Regions. The Bank has established correspondent SWIFT authentication partnerships with over 1,174 banking institutions in nearly 100 countries and regions. The Bank’s quality and comprehensive financial services have covered more than 360,000 corporate customers, 48.00 million individual customers, 89.00 million credit card customers and 51.00 million mobile banking customers. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2 017 年報 CORE VALUES • Integrity • Teamwork • Trust • Embrace Change VISION We Create Beauty in Motion with Intelligence

MINTH GROUP LIMITED (於開曼群島註冊成立之有限公司) 股份代號:425 敏實集團有限公司 年報 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2 017 年報 CORE VALUES • Integrity • Teamwork • Trust • Embrace change VISION We create beauty in motion with intelligence MISSION Make automobiles lighter, prettier and more intelligent TARGET To be the top 60 global auto parts supplier in 2021 CONTENTS 2 Corporate Information 3 Summary of Financial Information 4 Chairman’s Statement 5 Management Discussion and Analysis 17 Directors and Senior Management 20 Corporate Governance Report 26 Directors’ Report 37 Independent Auditor’s Report 40 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 41 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 43 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 45 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 47 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements * Should there be any discrepancy between the English and Chinese versions, the English version shall prevail. CORPORATE INFORMATION THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Citibank N.A. Hong Kong Branch Executive directors 44/F Citibank Tower Chin Jong Hwa (Chairman and Chief Executive No. 3 Garden Road Officer as redesignated on 10 August 2017) Central, Hong Kong Shi Jian Hui (resigned on 10 August 2017) Zhao Feng PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR AND Bao Jian Ya (resigned on 31 May 2017) TRANSFER OFFICE Chin Chien Ya SMP Partners (Cayman) Limited Huang Chiung Hui Royal Bank House — 3rd Floor Independent non-executive directors 24 Shedden Road P.O. Box 1586 Wang Ching Grand Cayman KY1-1110 Wu Fred Fong Cayman Islands Yu Zheng HONG KONG BRANCH SHARE COMPANY SECRETARY REGISTRAR AND TRANSFER OFFICE Yi Lei Li (appointed on 8 February 2018) Loke Yu (resigned on 8 February 2018) Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited REGISTERED OFFICE Shops 1712–1716 17th Floor, Hopewell Centre Cricket Square 183 Queen’s Road East Hutchins Drive, P.O. -

The Modern Development Vectors of Chinese Automotive Market

ISSN 2617-5932 Економічний вісник. Серія: фінанси, облік, оподаткування. 2020. Вип. 6 13 УДК 339.13.017:629.331 JEL L62 DOI 10.33244/2617-5932.6.2020.13-19 Ya. Belinska, Doctor of Economics, Professor e-mail: [email protected] ORCID ID 0000-0002-9685-0434; T. Fedorova, University of the State Fiscal Service of Ukraine e-mail: [email protected] ORCID ID 0000-0002-7827-068X THE MODERN DEVELOPMENT VECTORS OF CHINESE AUTOMOTIVE MARKET The article examines the essence and aspects of the Chinese car market development. The effect of this development on the structure of supply and demand for cars in different countries is analyzed. The features of the government sponsorship policy for new energy vehicles are characterized. It is estimated that China’s automotive industry ranks the first place in the world ranking for the number of manufactured and sold cars. The need to explore current tendencies in Chinese automotive sector and its impact on the global car market in general has been determined. There are made conclusions regarding measures to maintain China’s position on the global automotive market. Key words: the automotive market of China, government sponsorship policy, subsidies, joint ventures, new energy vehicles. Я. В. Белінська, Т. Ю. Федорова. Тенденції розвитку автомобільного ринку Китаю На сучасному етапі поглибленого розвитку міжнародних економічних відносин постає питання визначення Китаю як одного з локомотивів глобалізації та її проявів. Важливими складовими успіху Китаю є експорт автомобільної продукції, покращення транспортної інфраструктури, інвестиції в автомобільну промисловість та отримані переваги після вступу до СОТ (Світової організації торгівлі). Наразі китайські бренди автомобілів користуються великим попитом на закордонних ринках та в межах самого Китаю, при цьому спостерігається баланс між обсягами продажів та оптимальними цінами на продукцію. -

Notice of Convocation of the 95Th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders

Securities Code: 6444 June 8, 2021 Notice of Convocation of the 95th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders Dear Shareholders: It is our pleasure to announce that the 95th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders of Sanden Holdings Corporation (hereinafter referred to as “Sanden” or “Company”) will be held as stated below. In order to prevent the spread of infection of novel coronavirus (COVID-19), we recommend that shareholders refrain from attending the Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders wherever possible, and request that you exercise your voting rights in advance by mail or via the Internet, etc. Please review “The Reference Materials for the Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders” attached here and exercise your voting rights no later than 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, June 24, 2021. Sincerely, Katsuya Nishi Representative Director & President, Sanden Holdings Corporation 20, Kotobuki-cho, Isesaki City, Gunma Prefecture - 1 - Details of the Meeting 1. Date and time: Friday, June 25, 2021, 10:00 a.m. (The reception will start at 9:30 a.m.) This year’s Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders will be held in June as is the case in normal years, though the last year’s meeting was held in July due to influence of COVID-19. 2. Venue: Isesaki City Cultural Hall 3918 Showa-cho, Isesaki City, Gunma Prefecture 3. Meeting agenda: Items to be reported (1) Business Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the 95th Fiscal Year (from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021) and Reports of the Accounting Auditor and the Audit & Supervisory Board on the Consolidated Financial Statements (2) Non-Consolidated Financial Statements for the 95th Fiscal Year (from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021) Agenda items to be resolved Item 1: Election of Seven (7) Directors Item 2: Election of Four (4) Audit & Supervisory Board Members Item 3: Election of Eight (8) Directors Item 4: Amendments to the Articles of Incorporation 4. -

Law and Policy on the Development and Promotion of the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Market in China

Journal of Asian Electric Vehicles, Volume 16, Number 1, June 2018 Law and Policy on the Development and Promotion of the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Market in China Dennis Nikolaus Blatt KoGuan Law School, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, [email protected] Abstract China’s commitment towards becoming more innovative and environmentally-friendly, has led to the implementa- tion of a myriad of policies to fulfill future development plans; which has subsequently allowed the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) market to thrive. The NEV market has benefitted from policies which incentivize and prioritize in- dustries in the field of innovation and environmental technology, in addition to policies providing generous sub- sidies specifically towards the manufacturing and sales of NEVs. As China’s NEV market continues to grow at a rapid pace, this paper will analyze the significance played by policies implemented at various government levels, towards facilitating the development and promotion. Keywords ly, it removes skepticism over the lack of facilities, as China, policies, development, promotion, new energy subsidies are also provided to manufacturers of charg- vehicle ing facilities. The NEV market has also benefitted through certain restrictions placed on their emission- 1. INTRODUCTION based counterparts, thus creating a market-friendly China is currently the world’s largest electric vehicle environment for NEVs. market, and having set a sales target of 5 million New Currently, the Chinese NEV market is a subsidy driven Energy Vehicles (NEVs) by 2020, has led to the im- market, and has surpassed the United States in terms plementation of policies at various government levels, of sales volume, by achieving a sales total of 336,000 to help facilitate further advancements towards the NEVs in 2016, according the statistics provided by development and promotion of the NEV market.