Crisis Narrative and the Paradox of Erasure: Making Room for Dialectic Tension in a Cancel Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Kentucky Softball Media Guide

2021 KENTUCKY SOFTBALL MEDIA GUIDE T ABLE OF C ONTENTS M EDIA I NFOR M ATION 2021 Television Spot/Photo Chart ............................................................................................................ 2 TO THE MEDIA 2021 Roster .............................................................................................................................................. 3 The 2021 University of Kentucky soft- 2021 Quick Facts ....................................................................................................................................... 4 ball media supplement is intended to answer any questions you might 2021 Schedule .......................................................................................................................................... 5 have about the season. If you need Renee Abernathy ...................................................................................................................................... 6 additional information, special stories, Grace Baalman.......................................................................................................................................... 7 pictures or have any questions, please Jaci Babbs ................................................................................................................................................. 8 feel free to contact us at the Athletics Emmy Blane ............................................................................................................................................. -

2016 Schedule 1 Welcome to the University of Kentucky and K Week 2016! We Have Been Preparing for Your Arrival and Are Very Excited That You Are Here

2016 Schedule 1 Welcome to the University of Kentucky and K Week 2016! We have been preparing for your arrival and are very excited that you are here. K Week, the fall welcome week for all new students, is designed to make your transition to UK and to college life as smooth as possible. In the following schedule, you will find a wide variety of sessions, events, and social activities to help you get to know campus better, find answers to your questions, and make new friends. We want you to have fun and learn about your new home! Welcome Wildcats! It is my pleasure to welcome you to your home away from home. During your time here, you will create some of life’s greatest memories, build lasting relationships with your peers, and experience a world of opportunity and growth. Campus is undergoing a significant transition, but K Week will provide you with the best introduction to “seeing blue” at the University of Kentucky. From navigating our beautiful campus as you find your first class to attending events over the next several days, K Week is a crash-course in all things UK. As you embark on this journey, take advantage of new possibilities and embrace different ideas. Over the next several weeks, you will begin to make friends; meet faculty and staff; and spend time with alumni who walked many of the same paths when they were students. Enjoy it and discover new communities that will support your success as a student. You will also be challenged academically and socially – lean on your network, faculty, staff, and friends to help you throughout your time on campus. -

University of Kentucky (PDF)

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REGION III DELAWARE OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS KENTUCKY THE WANAMAKER BUILDING, SUITE 515 MARYLAND 100 PENN SQUARE EAST PENNSYLVANIA PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107-3323 WEST VIRGINIA January 31, 2017 IN RESPONSE, PLEASE REFER TO: 03146002 Dr. Eli Capilouto Office of the President University of Kentucky 101 Main Building, Lexington, KY 40506-0032 Dear President Capilouto: This letter is to notify you of the resolution of the above-referenced compliance review that was initiated by the U.S. Department of Education (Department), Office for Civil Rights (OCR), under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Title IX), 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681 et seq., and its implementing regulation at 34 C.F.R. Part 106. The compliance review assessed whether the University of Kentucky (the University) provided male and female students an equal opportunity to participate in the University’s intercollegiate athletic program by effectively accommodating their interests and abilities and providing opportunities for financial assistance to members of both sexes in proportion to the participation rate of men and women in the intercollegiate athletics program. OCR’s compliance review also examined whether the University provided equal athletic opportunities for male and female students with regard to the benefits and opportunities in all other aspects of the University’s intercollegiate athletics program, as described below. OCR is responsible for enforcing Title IX and its implementing regulation, which prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex in any education program or activity operated by a recipient of Federal financial assistance. The University is a recipient of Federal financial assistance from the Department. -

2019 Kentucky Football Prospectus

2019 PREVIEW 2019 KENTUCKY FOOTBALL PROSPECTUS TABLE OF CONTENTS Athletics Communications & Public Relations Staff Quick Facts 2 Covering Kentucky Football 3-4 Numerical Roster 5-6 Alphabetical Roster 7-8 Tony Neely Susan Lax Matt May Evan Crane Eric Lindsey Assistant AD/Communica- Director/Communications Asst. Director/ Assoc. Director/ Director/Communications tions & Public Relations & Public Relations Communications & PR Communications & PR & Public Relations Offensive Players by Position 9 (Mark Stoops Contact) (Primary Football Contact) (Secondary FB Contact) (Press Box Coord./Credentials) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Defensive Players by Position 10 Positional Breakdown 11 Quick Notes 12-21 Kroger Field 22 Deb Moore Jake Most Chris Shoals Assoc. Director/ Asst. Director/ Asst. Director/ Communications & PR Communications & PR Communications & PR [email protected] When Was the Last Time ... 23 [email protected] [email protected] 2018 Statistics 24-25 Head Coach Mark Stoops 26-29 Assistant Coaches 30-31 Connor Link Camiran Moore Stephanie Guy CPR Assistant CPR Assistant Office Coordinator Dr. Eli Capilouta, President 32 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Strategic Communications Staff Mitch Barnhart, Director of Athletics 33 Cats on the Map 35 Returning Player Biographies 36-70 2019 Newcomer Bios 71-77 Guy Ramsey Noah Richter Tim Letcher Britney Howard Chet White Director of Strategic Strategic Communication Website Coordinator Staff Photographer Staff Photographer Communications Assistant [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOLLOW KENTUCKY FOOTBALL [email protected] [email protected] ON SOCIAL MEDIA FIND THE FOLLOWING 2019 UK FOOTBALL SCHEDULE @UKFootball @CoachSchlarman @UKCoachStoops @CoachJonSumrall INFORMATON ON 8/31 Toledo [SECN] Noon @CoachGran @CoachClink UKATHLETICS.COM: 9/7 E. -

University of Kentucky 8 Regional Energy Innovation Forum Lexington, Kentucky • April 21, 2016

University of Kentucky 8 Regional Energy Innovation Forum Lexington, Kentucky • April 21, 2016 April 21, 2016 University of Kentucky Post-Forum Report 8-2 Exploring Regional Opportunities in the U.S. for Clean Energy Technology Innovation • Volume 2 Contents Opening Remarks ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Secretary Moniz remarks ............................................................................................................................. 3 Q&A .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Panel I: Innovation, Combustion and CCS - David Mohler, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Fossil Energy, Moderator ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Dr. Jeff Phillips, Senior Program Manager, EPRI ....................................................................................... 5 Dr. Kunlei Liu, Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky ............................................ 6 Roxann Laird, Director, National Carbon Capture Center ........................................................................ 6 George Koperna, VP, Advanced Resources International ......................................................................... 7 Q&A ......................................................................................................................................................... -

2018 Newsletter

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY 2018 Newsletter From the Chair The 2017-2018 academic year has been a very productive and eventful one. I am grateful this year, as always, to our alumni and friends who have shared their expertise with us, have mentored our students, and have contributed financially to the History Department. It gives me great pleasure to watch our community draw together to support one another. Our outstanding faculty thrive as they receive endowed fellowships; our graduate students benefit from more robust financial support and new opportunities to explore career options; our undergraduates gain access to a wide variety of high- TABLE OF CONTENTS impact internship and travel opportunities. Many thanks for your Meet Our New Faculty………….... 3 generosity! Vietnam Lecture Series……….…...5 Roland’s 100th Birthday………. …7 One of the many highlights from this past year was welcoming Undergraduate Internships……...8 Professor Emeritus Ron Eller back to the University of Kentucky for a Faculty News …………………….....12 very-well received History Department Alumni Lecture entitled, Emeriti Faculty and Staff…….....18 “Appalachia in the Age of Trump: Uneven Ground Revisited.” Another Student News………………………..19 Alumni News ……………………….26 notable gathering was our Washington DC Alumni and Friends Reunion 2017—2018 Graduation during the AHA in January 2018, with delicious food and drink News…………………………….……..33 provided by our generous hosts Dan Crowe and Leslee Gilbert. Dr. In Memoriam ………………….…..37 Gilbert also serves as chair of our History Advisory Committee. It was Thank You …………………………..38 wonderful to see a cross-section of young Washington DC-based _________________ Dean of Arts and Sciences alumni along with many students and colleagues from years past. -

Eli Capilouto) VER2

UKY Video Production | 2019-02-24 BTB (Eli Capilouto) VER2 (SINGING) On, on, U of K. We are right for the fight today. Hold that ball and hit that line. Every Wildcat star will shine. We'll fight, fight, fight for the blue and white. [MUSIC PLAYING] SPEAKER: From the campus of the University of Kentucky, you're listening to Behind the Blue. KODY KISER: This year marks the 70th year of integration at the University of Kentucky due to the efforts of Lyman T. Johnson, who broke the color barrier with his successful legal challenge in 1949. As progress has been made since that time, more can and will be done. I'm Kody Kiser with UK PR and marketing. On this edition of Behind the Blue, University of Kentucky President Eli Capilouto sat down with UK Public Relations and Strategic Communications Intern Aaron Porter Jr. to discuss the importance of Lyman T. Johnson's historic action, the progress the school has made, and more room for improvement in the areas of belonging and diversity on UK's campus. AARON PORTER: My name is Aaron Porter. And today, we have the 12th president of the University of Kentucky with us today, President Eli Capilouto. We thank you for coming in today, sir. How are you doing today? ELI CAPILOUTO: I'm great, Aaron. How are you? AARON PORTER: I'm good. I'm good. As you know, February is-- well, 2019 the year marks the 17th year of integration here on UK's campus. 70 years ago, Lyman T. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees University of Kentucky Tuesday, May 1, 2018 the Board of Trustees of the Univers

Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees University of Kentucky Tuesday, May 1, 2018 The Board of Trustees of the University of Kentucky met on Tuesday, May 1, 2018, in Woodward Hall in the Gatton College of Business and Economics. A. Meeting Opened E. Britt Brockman, Chair of the Board of Trustees, called the meeting to order at 1:00 p.m. Chair Brockman asked Trustee Kelly Holland, Secretary of the Board, to call the roll. B. Roll Call The following members of the Board of Trustees answered the call of the roll: Jennifer Y. Barber, Claude A. “Skip” Berry, III, Lee X. Blonder, James H. Booth, E. Britt Brockman, Mark P. Bryant, Benjamin Childress, Michael A. Christian, Angela L. Edwards, Cammie DeShields Grant, Robert Grossman, David V. Hawpe, Kelly Sullivan Holland, Elizabeth McCoy, David Melanson, Derrick K. Ramsey, C. Frank Shoop, Sandra R. Shuffett, Robert Vance, and Barbara Young. Trustee Carol Martin “Bill” Gatton was not in attendance. Secretary Holland announced a quorum was present. The University administration was represented by President Eli Capilouto, Provost Dave Blackwell, Executive Vice President for Health Affairs Mark F. Newman, Executive Vice President for Finance and Administration Eric Monday, Vice President for University Relations Tom Harris, Vice President for Research Lisa Cassis, Chief of Staff Bill Swinford, and Vice President for Institutional Diversity Sonja Feist-Price. The University faculty was represented by Chair of the University Senate Council Katherine McCormick, and the University staff was represented by Chair of the Staff Senate Jon Gent. Guests and members of the news media were also in attendance. -

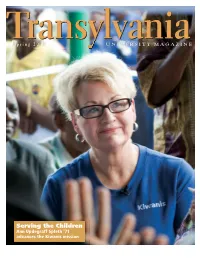

Spring2013pages.Qxd Layout 1

TTSpringransylvaransylva 2013 UNIVERSITYniania MAGAZINE Serving the Children Ann Updegraff Spleth ’71 advances the Kiwanis mission ALUMNI WEEKEND 2013 | APRIL 26–28 Replay your Transylvania years at Alumni Weekend Join your classmates, friends, and former professors April 26-28 for a look back at your college days. This year’s Alumni Weekend will include lots of fun, new activities. Spend Friday playing a round of golf, cheering on the horses at Keeneland Race Course, or attending a May term class on campus. Then celebrate Transy athletics at the Pioneer Hall of Fame induction and dinner before you rock the night away at the TGIF party at Atomic Café. Several classes will have informal gatherings around town that evening. Get fit on Saturday morning with a workout at the Beck Center or a tennis match with fellow alumni. And be sure to celebrate alumni achievements at the annual luncheon, which will feature performances by cast members of Transylvania’s production of the Broadway musical Pippin and ImprompTU, a student improv group. You won’t want to miss Saturday evening’s class reunion reception on Morrison Circle with music by student vocal groups. Pose for a class picture on the steps of Old Morrison. In case of rain, the reception and class photos will be moved to the Clive M. Beck Center. Then enjoy dinner or a reception with your classmates at a downtown restaurant. Watch your mailbox for details, visit the reunion website at www.transy.edu (select Alumni, News & Events, and Reunions/Alumni Weekend), or contact the alumni office at [email protected] or (800) 487-2679 for more information. -

1 United States District Court Eastern District

Case: 5:19-cv-00188-DCR Doc #: 1 Filed: 04/29/19 Page: 1 of 15 - Page ID#: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY CENTRAL DIVISION at LEXINGTON No. 5:19-cv-________________ ____________________________ BUCK RYAN, ) ) Plaintiff ) ) vs. ) Complaint ) Jury Trial Demanded DAVID BLACKWELL, ) In his Individual Capacity, ) ) JOSEPH REED, ) In his Individual Capacity, ) ) DEREK LANE, ) In his Individual Capacity, ) ) MIKE FARRELL, ) In his Individual Capacity, ) ) Defendants ) ____________________________) Plaintiff Buck Ryan (Ryan) for his complaint against defendants David Blackwell (Blackwell), in his individual capacity; Joseph Reed (Reed), in his individual capacity; Derek Lane (Lane), in his individual capacity; and Mike Farrell (Farrell), in his individual capacity states as follows: I Nature of the Action & Background 1. The most immediate and precipitating genesis of this case is an audit report instigated by the University of Kentucky’s General Counsel’s office that defamed Ryan, a long-standing and much-honored tenured university faculty member, by asserting falsely and wrongly that he had exploited his faculty position to reap undue monies from students in classes he taught by using one of 1 Case: 5:19-cv-00188-DCR Doc #: 1 Filed: 04/29/19 Page: 2 of 15 - Page ID#: 2 his books as required class materials. The audit report which was done by Reed remained secreted for many months after it was initially generated and its existence was wholly unknown to Ryan. 2. Reed’s audit report was initially disclosed to Ryan on or after April 30, 2018, when he was presented with it by Interim Director Farrell of the journalism school and then Dean Dan O’Hair of the university’s College of Communication and Information. -

Self-Study School of Information Science

School of Information Science Self-Study Master of Science in Library Science for the American Library Association Committee on Accreditation 2017 School organized and maintained for the purpose of graduate education in Library and Information Science School of Information Science Degree program being presented for accreditation by the Committee on Accreditation Master of Science in Library Science (MSLS) The program presented for accreditation is a 36-hour graduate degree program through which students earn the Master of Science in Library Science (MSLS) degree. The American Library Association first granted accreditation to the Bachelor of Science in Library Science at the University of Kentucky in 1942. The MSLS program was first awarded accreditation from the American Library Association in 1949 and has continuously maintained its accreditation. Parent Institution The University of Kentucky Chief Executive Officer, University of Kentucky Eli Capilouto, President Chief Academic Officer, University of Kentucky Tim Tracy, Provost (stepping down effective December 31, 2017) Principal Administrator, College of Communication and Information Dan O’Hair, Dean Principal Administrator, School of Information Science Jeff Huber, Director and Professor Regional Accrediting Agency and Status Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) Reaffirmed: 2013; Next Reaffirmation: 2023 Title and Version of the Standards Addressed in the Program Presentation Standards for Accreditation of Master’s Programs in Library and -

GREGORY A. LUHAN, Ph.D., AIA, RA, NCARB the Ward V

GREGORY A. LUHAN, Ph.D., AIA, RA, NCARB The Ward V. Wells Endowed Professor of Architecture Department Head of Architecture Address: 2704 Colony Vista Ct., Bryan, TX 77808 USA Studio: 859.492.5942 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://new.luhanstudio.com/ EDUCATION: Texas A&M University Dates Attended: 2013-2016 Major: Architecture William W. Caudill Endowed Graduate Research Fellowship in Architecture (2013-2016) Degree Received: Doctor of Philosophy; Ph.D. in Architecture (2016) Dissertation Title: Measurement of Self-Efficacy, Predisposition for Collaboration, and Project Scores in Architectural Design Studio Dissertation Committee: Dr. Mark J. Clayton (Chair), Dr. Jorge Vanegas, Dr. Valerian Miranda, Dr. Zofia Rybkowski Princeton University Dates Attended: 1996-1998 Major: Architecture Degree Received: Master of Architecture (1998) Thesis Title: Infrastructure: A West Side Story, An Idea for a Park in a City Thesis Committee: Ralph Lerner (Chair), Guy Nordenson Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Dates Attended: 1986-1991 Major: Architecture Degree Received: Bachelor of Architecture (1991) Thesis Title: The Bronx: Between Hard and Soft | Interpreting Negotiating Urban Voids Thesis Committee: Robert Dunay (Chair), Olivio Ferrari, Rudy Hunziker Professional Extern Program State University of New York/Rockland Dates Attended: 1985-1986 Major: Philosophy, Engineering—Honors Mentor/Talented Student (M/TS) Honors Program; Mentors: Dr. Samuel Draper, Dr. Libby Bay Phi Sigma Omicron Honor Society PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: