Oral History Transcript T-0003, Chick Finney and Martin Luther Mackay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History T-0001 Interviewees: Chick Finney and Martin Luther Mackay Interviewer: Irene Cortinovis Jazzman Project April 6, 1971

ORAL HISTORY T-0001 INTERVIEWEES: CHICK FINNEY AND MARTIN LUTHER MACKAY INTERVIEWER: IRENE CORTINOVIS JAZZMAN PROJECT APRIL 6, 1971 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Today is April 6, 1971 and this is Irene Cortinovis of the Archives of the University of Missouri. I have with me today Mr. Chick Finney and Mr. Martin L. MacKay who have agreed to make a tape recording with me for our Oral History Section. They are musicians from St. Louis of long standing and we are going to talk today about their early lives and also about their experiences on the music scene in St. Louis. CORTINOVIS: First, I'll ask you a few questions, gentlemen. Did you ever play on any of the Mississippi riverboats, the J.S, The St. Paul or the President? FINNEY: I never did play on any of those name boats, any of those that you just named, Mrs. Cortinovis, but I was a member of the St. Louis Crackerjacks and we played on kind of an unknown boat that went down the river to Cincinnati and parts of Kentucky. But I just can't think of the name of the boat, because it was a small boat. Do you need the name of the boat? CORTINOVIS: No. I don't need the name of the boat. FINNEY: Mrs. Cortinovis, this is Martin McKay who is a name drummer who played with all the big bands from Count Basie to Duke Ellington. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BILL HOLMAN NEA Jazz Master (2010) Interviewee: Bill Holman (May 21, 1927 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: February 18-19, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 84 pp. Brown: Today is Thursday, February 18th, 2010, and this is the Smithsonian Institution National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Oral History Program interview with Bill Holman in his house in Los Angeles, California. Good afternoon, Bill, accompanied by his wife, Nancy. This interview is conducted by Anthony Brown with Ken Kimery. Bill, if we could start with you stating your full name, your birth date, and where you were born. Holman: My full name is Willis Leonard Holman. I was born in Olive, California, May 21st, 1927. Brown: Where exactly is Olive, California? Holman: Strange you should ask [laughs]. Now it‟s a part of Orange, California. You may not know where Orange is either. Orange is near Santa Ana, which is the county seat of Orange County, California. I don‟t know if Olive was a part of Orange at the time, or whether Orange has just grown up around it, or what. But it‟s located in the city of Orange, although I think it‟s a separate municipality. Anyway, it was a really small town. I always say there was a couple of orange-packing houses and a railroad spur. Probably more than that, but not a whole lot. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Ithaca College Alumni Big Band

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-26-2008 Concert: Ithaca College Alumni Big Band Ithaca College Alumni Big Band Steve Brown Ray Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Alumni Big Band; Brown, Steve; and Brown, Ray, "Concert: Ithaca College Alumni Big Band" (2008). All Concert & Recital Programs. 6670. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/6670 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE ALUMNI BIG BAND Steve Brown and Ray Brown, musical directors Ford Hall Saturday, April 26, 2008 8:15 p.m. PROGRAM Straightahead City Ray Brow Bossa Barbara Steve Brown Arr. Ray Brown Sweet Angel Steve Brown Lyrics: Tish Rabe Two Birds, On~ Stone Steve Brown Embraceable You/Quasimodo Gershwin/Parker Arr. Ray Brown The Telephone Song Menescal/Boscoli/Gimbel .. Arr. Ray BrowU Bittersweet Willie Maiden Trans. Ray Brown The Best of Everything Tony Bennett Arr. Steve Brown Our Love Is Here To Stay George Gershwin Air. Ray Brown INTERMISSION Del Sasser Sam Jones Arr. Ray Brown PickYours·elf Up Fields/Kem Arr. Neal Hefti Trans. Tony DeSare Kayak Kenny Wheeler Arr. Ray Brown Barbara Horace Silver Arr. Ray Brown I Could Write A Book Rodgers/Hart Arr. Ray Brown The Thumb Wes Montgomery Arr. Ray Brown The Ballad of Thelonious Monk Jimmy Rowles Arr. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

As Fate Would Have It Pat Sajak and Vanna White would have been quite at home in New Orleans in January 1828. It was announced back then in L’Abeille de Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee) that “Malcolm’s Celebrated Wheel of Fortune” was to “be handsomely illuminated this and to-morrow evenings” on Chartres Street “in honour of the occasion”. The occasion was the “Grand Jackson Celebration” where prizes totaling $121,800 were to be awarded. The “Wheel of Fortune” was known as Rota Fortunae in medieval times, and it captured the concept of Fate’s capricious nature. Chaucer employed it in the “Monk’s Tale”, and Dante used it in the “Inferno”. Shakespeare had many references, including “silly Fortune’s wildly spinning wheel” in “Henry V”. And Hamlet had those “slings and arrows” with which to contend. Dame Fortune could indeed be “outrageous”. Rota Fortunae by the Coëtivy Master, 15th century In New Orleans her fickle wheel caused Ignatius Reilly’s “pyloric valve” to close up. John Kennedy Toole’s fictional protagonist sought comfort in “The Consolation of Philosophy” by Boethius, but found none. Boethius wrote, “Are you trying to stay the force of her turning wheel? Ah! Dull-witted mortal, if Fortune begins to stay still, she is no longer Fortune.” Ignatius Reilly found “Consolation” in the “Philosophy” of Boethius. And Boethius had this to say about Dame Fortune: “I know the manifold deceits of that monstrous lady, Fortune; in particular, her fawning friendship with those whom she intends to cheat, until the moment when she unexpectedly abandons them, and leaves them reeling in agony beyond endurance.” Ignatius jotted down his fateful misfortunes in his lined Big Chief tablet adorned with a most impressive figure in full headdress. -

Newsletternewsletter March 2015

NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER MARCH 2015 HOWARD ALDEN DIGITAL RELEASES NOT CURRENTLY AVAILABLE ON CD PCD-7053-DR PCD-7155-DR PCD-7025-DR BILL WATROUS BILL WATROUS DON FRIEDMAN CORONARY TROMBOSSA! ROARING BACK INTO JAZZ DANCING NEW YORK ACD-345-DR BCD-121-DR BCD-102-DR CASSANDRA WILSON ARMAND HUG & HIS JOHNNY WIGGS MOONGLOW NEW ORLEANS DIXIELANDERS PCD-7159-DR ACD-346-DR DANNY STILES & BILL WATROUS CLIFFF “UKELELE IKE” EDWARDS IN TANDEM INTO THE ’80s HOME ON THE RANGE AVAilable ON AMAZON, iTUNES, SPOTIFY... GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 Decatur Street New Orleans, LA 70116 phone: (504) 525-5000 fax: (504) 525-1776 email: [email protected] website: jazzology.com office manager: Lars Edegran assistant: Jamie Wight office hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm entrance: 61 French Market Place newsletter editor: Paige VanVorst contributors: Jon Pult and Trevor Richards HOW TO ORDER Costs – U.S. and Foreign MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter. Also you will be able to buy our products at a discounted price – CDs for $13.00, DVDs $24.95 and books $34.95. Membership continues as long as you order one selection per year. NON-MEMBERS For non-members our prices are – CDs $15.98, DVDs $29.95 and books $39.95. MAILING AND POSTAGE CHARGES DOMESTIC There is a flat rate of $3.00 regardless of the number of items ordered. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Remember Your August the Nineteenth, by The

AL MORGAN Reel X [of 2] August 19, 1958 Also present; William Russell rRussell:1 O.K., I guess it's going if .you want to give your name. You don't have to get close; just sit back and relax. [Morgan: 1 0. K. d' .t [Russell:1 It'll pick up anthing in the room. [M0rqan:1 Well, my name is Al Morgan- [Russell:1 Is [there?] any middle name by the way? [Norcran:1 No, well they-my full name-call me Albert, but I've always-everybody-I went [ j with says ?] they liked Al- [Russell:1 That's right. Th:at's all I ever heard. [Morgan:] For short. (Laughs) ? [Russell:1 [ . .I- ] I didn't know until last night I heard somebody call you Albert. When were you born? Remember your birth date? [Morgan :1 Oh yes, I was born, about forty-two years ago. That's August the nineteenth, by the way, today is my birthday. (Laughs) [Russell:] [ ? ?] Oh my; What a time to hit [ » What was tl-ie year then? Let me see:,, nineteen-- [Morgan:] Oh boy, let me see. We have to go- [Russell:] Porty-two- *t [Morgan:] Back, that should be from now, about- [Russell:1 1916, would that be about- [Morgan:] 19-uh-about 1912- [Russell:] 1912. [ Morgan:1 Something like that. [Russell:1 Yeah, well, anyway- [Morgan:] Just about. Well, it's close. AL MORGAN 2 Reel I [of 2] August 19, 1958 [Russell:] Yeah, do you remember your first music you ever heard when you were a kid? Was it your brothers' playing or [your folks?] [Morq-an:1 Well, yes, I remember lots about my brothers' playing, way before I ever started, you see. -

A Researcher's View on New Orleans Jazz History

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Format 6 New Orleans Jazz 7 Brass & String Bands 8 Ragtime 11 Combining Influences 12 Party Atmosphere 12 Dance Music 13 History-Jazz Museum 15 Index of Jazz Museum 17 Instruments First Room 19 Mural - First Room 20 People and Places 21 Cigar maker, Fireman 21 Physician, Blacksmith 21 New Orleans City Map 22 The People Uptown, Downtown, 23 Lakefront, Carrollton 23 The Places: 24 Advertisement 25 Music on the Lake 26 Bandstand at Spanish Fort 26 Smokey Mary 26 Milneburg 27 Spanish Fort Amusement Park 28 Superior Orchestra 28 Rhythm Kings 28 "Sharkey" Bonano 30 Fate Marable's Orchestra 31 Louis Armstrong 31 Buddy Bolden 32 Jack Laine's Band 32 Jelly Roll Morton's Band 33 Music In The Streets 33 Black Influences 35 Congo Square 36 Spirituals 38 Spasm Bands 40 Minstrels 42 Dance Orchestras 49 Dance Halls 50 Dance and Jazz 51 3 Musical Melting Pot-Cotton CentennialExposition 53 Mexican Band 54 Louisiana Day-Exposition 55 Spanish American War 55 Edison Phonograph 57 Jazz Chart Text 58 Jazz Research 60 Jazz Chart (between 56-57) Gottschalk 61 Opera 63 French Opera House 64 Rag 68 Stomps 71 Marching Bands 72 Robichaux, John 77 Laine, "Papa" Jack 80 Storyville 82 Morton, Jelly Roll 86 Bolden, Buddy 88 What is Jazz? 91 Jazz Interpretation 92 Jazz Improvising 93 Syncopation 97 What is Jazz Chart 97 Keeping the Rhythm 99 Banjo 100 Violin 100 Time Keepers 101 String Bass 101 Heartbeat of the Band 102 Voice of Band (trb.,cornet) 104 Filling In Front Line (cl. -

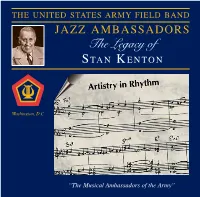

The Legacy of S Ta N K E N to N

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND JAZZ AMBASSADORS The Legacy of S TA N K ENTON Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Jazz Ambassadors is the Concerts, school assemblies, clinics, T United States Army’s premier music festivals, and radio and televi- touring jazz orchestra. As a component sion appearances are all part of the Jazz of The United States Army Field Band Ambassadors’ yearly schedule. of Washington, D.C., this internation- Many of the members are also com- ally acclaimed organization travels thou- posers and arrangers whose writing helps sands of miles each year to present jazz, create the band’s unique sound. Concert America’s national treasure, to enthusi- repertoire includes big band swing, be- astic audiences throughout the world. bop, contemporary jazz, popular tunes, The band has performed in all fifty and dixieland. states, Canada, Mexico, Europe, Ja- Whether performing in the United pan, and India. Notable performances States or representing our country over- include appearances at the Montreux, seas, the band entertains audiences of all Brussels, North Sea, Toronto, and New- ages and backgrounds by presenting the port jazz festivals. American art form, jazz. The Legacy of Stan Kenton About this recording The Jazz Ambassadors of The United States Army Field Band presents the first in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contri- butions to big band jazz. Designed primarily as educational resources, these record- ings are a means for young musicians to know and appreciate the best of the music and musicians of previous generations, and to understand the stylistic developments leading to today’s litera- ture in ensemble music. -

Oral History Transcript T-0011B, Interview with Sammy Long, April 18, 1973

ORAL HISTORY T-0011b INTERVIEW WITH SAMMY LONG INTERVIEWED BY IRENE CORTINOVIS JAZZMEN PROJECT APRIL 18, 1973 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. CORTINOVIS: What kind of a man was Fate Marable? LONG: Oh, he was really a swell fellow and a very good musician. The difference with Fate from other piano players was that Fate gave the orchestra a better foundation. Lot of the men found that out when they went to play with other guys. [Later he added that Fate Marable was a pretty heavy drinker and that the Streckfuses who "had brought him along" used to lay Fate off every now and then, but would always take him back.] CORTINOVIS: I discussed his many visits to New Orleans with him and he made the following comments: CORTINOVIS: Did you ever play with any of the New Orleans musicians? LONG: Sure. When I played with Fate and with Dewey Jackson, we would only bring six pieces down the river and then when we would get to New Orleans, we would pick up three or four more. Willie Humphrey played clarinet for us. You know, he still plays with the Preservation Hall band, I saw him last summer. And George Foster played bass with us, too. Sometimes there would be two bands on the boat...ours and one from New Orleans. There was a Celestin's ["Papa" Oscar Celestin] Band and another one led by Sam Morgan.