The Golden Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2018 Newsletter

San Francisco Ceramic Circle An Affiliate of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco February 2018 P.O. Box 26773, San Francisco, CA 94126 www.patricianantiques.com/sfcc.html SFCC FEBRUARY LECTURE A Glittering Occasion: Reflections on Dining in the 18th Century Sunday, FEBRUARY 25, 2017 9:45 a.m., doors open for social time Dr. Christopher Maxwell 10:30 a.m., program begins Curator of European Glass Gunn Theater, Legion of Honor Corning Museum of Glass About the lecture: One week later than usual, in conjunction with the Casanova exhibition at the Legion of Honor, the lecture will discuss the design and function of 18th-century tableware. It will address the shift of formal dining from daylight hours to artificially lit darkness. That change affected the design of table articles, and the relationship between ceramics and other media. About the speaker: Dr. Christopher L. Maxwell worked on the redevelopment of the ceramics and glass galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, with a special focus on 18th-century French porcelain. He also wrote the V&A’s handbook Eighteenth-Century French Porcelain (V&A Publications, 2010). From 2010 to 2016 he worked with 18th-century decorative arts at the Royal Collections. He has been Curator of European Glass at the Corning Museum of Glass since 2016. Dr. Maxwell is developing an exhibition proposal on the experience of light and reflectivity in 18th-century European social life. This month, our Facebook page will show 18th-century table settings and dinnerware. The dining room at Mount Vernon, restored to the 1785 color scheme of varnished dark green walls George Washington’s Mount Vernon, VA (photo: mountvernon.org SFCC Upcoming Lectures SUNDAY, MARCH 18, Gunn Theater: Gunn Theater: Jody Wilkie, Co-Chairman, Decorative Arts, and Director, Decorative Arts of the Americas, Christie’s: “Ceramics from the David Rockefeller collection.” SUNDAY, APRIL 15, Sally Kevill-Davies, cataloguer of the English porcelain at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, will speak on Chelsea porcelain figures. -

French Soft-Paste Porcelain During the 17Th and 18Th Centuries

French soft-paste porcelain during the 17th and 18th centuries Edgar Vigário July 2016 Abstract In 1673 Louis XIV give to Edme and Louis Poterat the privilege of porcelain manufacture similar to the one bought from China becoming Rouen the first production center of soft-paste in France. After it, others follow being the better documented listed in this article. 1 Figure 1 - Portrait of Madame de Montespan (detail); oil on canvas; Henri Gascard; 1675 - 1685; © Morgane Mouillade. Index copy the Chinese porcelain that arrived in the Introduction 1 country in large quantities, initially from de Dutch Rouen (1673 – 1696) 1 VOC and after 1664 mainly by the Compagnie Factory of Saint-Cloud (1693 - 1766) 4 Française des Indes Orientales. The new material Factory of Ville l'Evêque (1711 - 1766) 5 had as drawbacks, a high production lost which Factory of Lille (1711 - 1730) 6 Factory of Chantilly (1725 - 1800) 6 dramatically increase costs and the difficulty of Factory of Mennecy (1734 - 1773) 8 creating big pieces, due to the paste's low elasticity, Factory of Bourg-la-Reine (1773 - 1804) 11 however, these difficulties weren't enough to Factory of Sceaux (1748 - c. 1810) 11 prevent the creation of several factories on the Factory of Vincennes (1741 - 1756) and Sèvres (1756 - 1804) 12 th Factory of Orléans (1753 - 1768) 14 French territory during the late 17 century and the Factory of Crépy-en-Valois (1762 - 1770) 15 beginnings of the 18th century from whom stands Factory of Étiolles (1766 -?) 15 out by their historical significance and/or exquisite Factory of Arras (1770 - 1790) 15 production the workshops and factories that are References 16 listed in this document. -

Some Continental Influences on English Porcelain

52925_English_Ceramics_vol19_pt3_book:Layout 1 24/7/08 09:12 Page 429 Some Continental Influences on English Porcelain A paper read by Errol Manners at the Courtauld Institute on the 15th October 2005 INTRODUCTION Early French soft-paste porcelain The history of the ceramics of any country is one of We are fortunate in having an early report on Saint- continual influence and borrowing from others. In the Cloud by an Englishman well qualified to comment case of England, whole technologies, such as those of on ceramics, Dr. Martin Lister, who devoted three delftware and salt-glazed stoneware, came from the pages of his Journey to Paris in the year 1698 (published continent along with their well-established artistic in 1699) to his visit to the factory. Dr. Lister, a traditions. Here they evolved and grew with that physician and naturalist and vice-president of the uniquely English genius with which we are so Royal Society, had knowledge of ceramic methods, as familiar. This subject has been treated by others, he knew Francis Place, 2 a pioneer of salt-glazed notably T.H. Clarke; I will endeavour to not repeat stoneware, and reported on the production of the too much of their work. I propose to try to establish Elers 3 brothers’ red-wares in the Royal Society some of the evidence for the earliest occurrence of Philosophical Transactions of 1693. 4 various continental porcelains in England from Dr.. Lister states ‘I saw the Potterie of St.Clou documentary sources and from the evidence of the (sic), with which I was marvellously well pleased: for I porcelain itself. -

LADY CYNTHIA POSTAN COLLECTION COLLECTION of French and Other 18Th Century Porcelain

E & H MANNERS MAY 2015 E & H MANNERS MAY THE LADY CYNTHIA POSTAN THE LADY CYNTHIA POSTAN COLLECTION THE LADY CYNTHIA POSTAN COLLECTION of French and Other 18th Century Porcelain To be exhibited at E & H MANNERS THE LADY CYNTHIA POSTAN COLLECTION of French and Other 18th Century Porcelain To be exhibited for sale at E & H MANNERS 66C KENSINGTON CHURCH STREET LONDON W8 4BY 21st to 29th May 2015 [email protected] www.europeanporcelain.com 020 7229 5516 a warm Francophile – including attachment to her applied to her specialisation in Sèvres, Vincennes, Parisian sister- and brother-in-law, and Munia’s Chantilly and Saint Cloud. close academic links with France. It has also given her pure pleasure – in the objects Although she started collecting earlier, their themselves, displayed in her homes in Cambridge; in year in Paris in 1961–62, when Munia was at the the period and world which they originally inhabited; Sorbonne, gave her a heaven-sent opportunity to and in the community of her fellow-enthusiasts immerse herself even further in the world of the - collectors, museum curators and dealers alike porcelain of the French eighteenth century. A wide - in which she loved to play her part. The French circle of French friends, including distinguished Porcelain Society is its formal embodiment, and it academic historians, some of whose works she would be wrong to exclude names from the list of later translated for publication, shared her high her friends and mentors, but among them Dame cultural values. Rosalind Savill, the late Ian Lowe, Errol Manners, Despite the eclecticism of her wider collecting Robert Williams and Adrian Sassoon stand out habits for over more than half a century, this in my memory at least. -

Fine European Ceramics Fine European

New Bond Street, London | 2 July 2019 New Bond Street, Fine European Ceramics Fine European Fine European Ceramics I New Bond Street, London I 2 July 2019 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Registered No. 4326560 Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Matthew Girling CEO, Asaph Hyman, Caroline Oliphant, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Edward Wilkinson, Geoffrey Davies, James Knight, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Jonathan Fairhurst, Leslie Wright, Rupert Banner, Simon Cottle. Fine European Ceramics New Bond Street, London | Tuesday 2 July 2019 at 2pm Lots 51-294 to be sold following the sale of Important Meissen Porcelain from a Private Collection, Part II VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Saturday 29 June Nette Megens Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm The United States Government 11am to 5pm Head of Department +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 has banned the import of ivory Sunday 30 June +44 (0) 20 7468 8348 into the USA. Lots containing ivory are indicated by the 11am to 5pm [email protected] PHYSICAL CONDITION OF symbol printed beside the Monday 1 July LOTS IN THIS AUCTION Ф 9am to 4.30pm Sebastian Kuhn PLEASE NOTE THAT ANY lot number in this catalogue. Tuesday 2 July Department Director REFERENCE IN THIS by appointment +44 (0) 20 7468 8384 CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL REGISTRATION [email protected] CONDITION OF ANY LOT IS FOR IMPORTANT NOTICE SALE NUMBER GENERAL GUIDANCE ONLY. Please note that all customers, 25311 Sophie von der Goltz INTENDING BIDDERS MUST irrespective of any previous Specialist SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO activity with Bonhams, are +44 (0) 20 7468 8349 THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT required to complete the Bidder CATALOGUE [email protected] AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 OF Registration Form in advance of £25.00 THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS the sale. -

Sculptural Splendour

Sculptural Splendour ALL EXHIBITS ARE FOR SALE 15 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DB Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 6550 Fax: +44 (0)20 7389 6556 Email: [email protected] www.haughton.com Foreword It is with great pleasure that we introduce you to our collection of porcelain entitled Sculptural Splendour. Many of the pieces have been chosen with the clear theme of the modeller’s art and his representation of natural imagery. It is a triumph of Nature’s zest that is captured and tooled by man’s imagination and enhanced to create both anthropomorphic and fantastical forms, redolent of an age of peace, prosperity, and plenty during the eighteenth century. These forms are in turn loaded with symbols of love and desire to be strewn across tables and pleasure domes of the wealthy during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to startling effect. The rare Chelsea Indian Prince, (no. 1) in the catalogue symbolises the level of secret intrigue that Europe had for the Eastern way of life, showing a turbaned moor with all the trappings of the exotic vested in his silks and, carrying an arrow with which to subdue the strong and the wild, making him a symbol of love and profanity. This theme is extended with the inclusion of a number of rare moorish models including the Worcester Turks (no. 11) modelled by John Toulouse, which are earlier than most with their delightful pastel shades, and taken from Meissen originals after J.J. Kaendler. The rare Kloster-Veilsdorf figure of the Judge Cadileskier (no. -

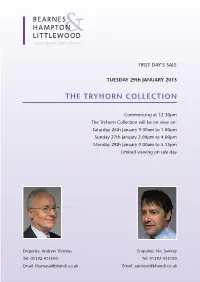

The Tryhorn Collection

FIRST DAY’S SALE TUESDAY 29th JANUARY 2013 THE TRYHORN COLLECTION Commencing at 12.30pm The Tryhorn Collection will be on view on: Saturday 26th January 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 27th January 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 28th January 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Tryhorn Collection The collection of the late Donald Tryhorn of Kingsbridge in Devon. Comprising 154 lots was accumulated with almost curatorial care over a period of 30 years. Although a private man, he was a regular face in both provincial and national auction rooms, indeed the collection includes a number of pieces acquired from the dispersal of other major collections. He was also an active buyer from many of the most recognised dealers of 18th century porcelain who no doubt will be keen to repatriate the odd ‘old friend’. He kept at least a dozen notebooks in which he recorded and cross referenced his acquisitions and in addition recorded the details of other pieces of interest that he had come across in salerooms but was unable to purchase at the time. These note and scrapbooks were almost constantly updated and annotated when new information came to light or when he perceived a previously overlooked characteristic. Donald Tryhorn’s collection has several main themes but primarily his passion was for Bow porcelain which is reflected in the fact that nearly a quarter of the lots in the collection are from that factory and range from simple tea bowls and large mugs through to desirable bottle vases. -

The Sarah Belk Gambrell Collection of European Porcelain

THE SARAH BELK GAMBRELL COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PORCELAIN Thursday, June 24, 2021 DOYLE.COM THE SARAH BELK GAMBRELL COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PORCELAIN AUCTION Thursday, June 24, 2021 at 10am Eastern EXHIBITION Friday, June 18, Noon – 5pm Saturday, June 19, Noon – 5pm Sunday, June 20, Noon – 5pm Monday, June 21, 10am – 6pm And by Appointment at other times Safety protocols will be in place with limited capacity. Please maintain social distance during your visit. Please check DOYLE.com for our Terms of Guarantee and Conditions of Sale. LOCATION Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers 175 East 87th Street New York, NY 10128 212-427-2730 This Gallery Guide was created on 6-23-21 Please see addendum for any changes The most up to date information is available On DOYLE.COM Sale Info View Lots and Place Bids Doyle New York 1 2 Elizabeth I Silver-Mounted Rhenish Böttger Red Stoneware Coffee Pot and Cover Saltglazed 'Tigerware' Jug Circa 1710-15, designed by J.J. Irminger Circa 1580, the silver mount inscribed on the Of squared pear form, the conforming domed hinge 'PETER ELY, OBT. 1684', on the cover cover with pagoda knop, the scroll handle with 'GEO. GUNNING 1815 WATERLOO' and on the channeled sides and a studded exterior, the underside of the foot 'GIVEN BY KING squared curved spout issuing from the gaping CHARLES THE SECOND' and 'G.G. TO M.G. jaws of a scaly serpent, a double-scroll bridge 1834' support above, each side of the body lightly Globular with cylindrical neck and loop handle polished, on a flaring stepped square foot. -

Guide to the Porcelain Room Seattle Art Museum

Guide to the Porcelain Room Seattle Art Museum Guide to the Porcelain Room Seattle Art Museum Enduring fame—the goal of so many fig- Tiepolo’s Allegory Tiepolo designed an allegory in which ures in history—was the promise of art. Fame crowns the golden-robed figure of The image that crowns the Porcelain Room Valor with a laurel wreath, as Time watches was originally painted on the ceiling of the Porto family palace helplessly from the shadows below, his scythe overturned. The designed by Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), the great Renaissance fresco was removed from the palace in the early part of the twenti- architect, in the town of Vicenza. It was commissioned from eth century, transferred to canvas, and sold to a German collector. Tiepolo, the greatest Venetian artist of the eighteenth century, In 1951 the Kress Foundation bought the fresco; the Foundation to celebrate the bravery of the Porto family, which was noted had already purchased the sketch for it in 1948. A painting that for generations of military accomplishments. Tiepolo first made a originally was an integral part of a building thus became a mobile fluid oil sketch, here displayed on the wall, to show to his patron work of art, ending up in Seattle and spreading the fame of the before commencing work on the final painting. Porto family more widely than they could ever have imagined. — Chiyo Ishikawa Deputy Director of Art and Curator of European Painting and Sculpture Seattle Art Museum The Triumph of Valor over Time, ca. 1757 The Triumph of Valor over Time Fresco transferred to canvas (preparatory sketch), ca. -

Tasteforporcelain Online.Pdf

SNITE MUSEUM OF ART This publication was made possible by generous gifts from Mr. Ralph M. Hass. © 2014 Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame ISBN: 978-0-9753984-5-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931431 3 Gabriel P. Weisberg With contributions by Rachel Schmid and Elizabeth Sullivan research assistance by Yvonne Weisberg SNITE MUSEUM OF ART University of Notre Dame 4 6 Acknowledgments Charles R. Loving 8 An Early Beginning: The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory and the Marten Collection Gabriel P. Weisberg Contents Catalogue Entries: Rachel Schmid, Elizabeth Sullivan and Gabriel P. Weisberg Doccia Porcelain Manufactory 16 1 Salt Cellar or Sweetmeat Dish Meissen Porcelain Manufactory 24 2 Tea Bowl and Saucer 32 3 Boar’s Head Tureen 36 4 Swan Service Charger 40 5 Billy Goat 44 6 Covered Fountain with Two Swans 50 7 Dancing Columbine 54 8 Cup and Saucer Chantilly Manufactory 60 9 Sugar Bowl and Cover Sceaux Pottery and Porcelain Manufactory 64 10 Cup and Saucer Saint-Cloud Porcelain Manufactory 68 11 Tureen Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory 74 12 La Savoyarde tenant un chien 78 13 Vase, à Oreilles 82 14 Teapot (Théière Calabre) 88 15 Punch Bowl 90 16 Cup and Saucer (Tasse Boquet) 94 17 La Nourrice Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory 100 18 Soup Plate with “Hans Sloane” Botanical Decoration 104 19 Pair of Écuelles, Covers and Stands 108 20 Perfume Vase Frankenthal Porcelain Manufactory 114 21 Figure Group: Allegory of Time Saving Truth from Falsehood 118 22 Teapot and Cover 122 Checklist of Marks 124 Selected Bibliography 2 4 5 Acknowledgments The Snite Museum of Art takes great pleasure in publishing this collec- pieces related to those in the Marten collection, providing firsthand The authors have elegantly elucidated the many influences on eighteenth- tion catalog for our Virginia A. -

Moustiers Ceramics Gifts from the Eugene V

WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION MOUSTIERS CERAMICS GIFTS FROM THE EUGENE V. AND CLARE E. THAW COLLECTION AUGUST 2, 2017 – JANUARY 2 1, 2019 1 industry in France, at Vincennes and then Sèvres, fell under royal patronage and the porcelain created MOUSTIERS there was not available for purchase. These decorated tin-glazed earthenware ceramics were clearly sought after in their day, as is evidenced by the signatures CERAMICS often found on the wares. They also held an irresistible appeal to collectors starting in the early twentieth FROM THE EUGENE V. century, when eighteenth-century French style was seen as the height of design, for the charm of colorful, AND CLARE E. THAW often amusing depictions of figures and flowers. COLLECTION The combination of engraved decorative print sources and the connection with textile motifs has been observed by Rebekah Pollock, a graduate of Cooper Hewitt/Parsons School of Design master’s program in This booklet accompanies an exhibition celebrating the History of Design and Curatorial Studies and the the gift of a substantial collection of Moustiers scholar who wrote this booklet’s essay. She shows the ceramics from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw links between Moustiers ceramics and broader French collection, given to Cooper Hewitt from 2006 to 2017. decorative arts using objects in Cooper Hewitt’s other The Thaws received their first piece of Moustiers curatorial departments, making the case for how ceramics as a wedding present from someone whose important cross-disciplinary connections are in the taste and knowledge they admired, and they set out to design field, and how proximity of such collections at explore the varieties of ornament, form, and function the museum helps to make these connections. -

Kw 2011 Cover Updated.Indd

Front cover: the homestead, Keerweder The Contents of Keerweder CAPE TOWN 22 October 2012 CT 2012/4 Tel: +27 (0) 21 683 6560 Mobile : +27 (0) 78 044 8185 Fax: +27 (0) 21 683 6085 [email protected] The Oval, 1st Floor Colinton House, 1 Oakdale Road, Newlands, 7700 Postnet Suite 200, Private Bag X26, Tokai, 7966 JOHANNESBURG Tel: +27 (0) 11 728 8246 Mobile : +27 (0) 79 367 0637 Fax: +27 (0) 11 728 8247 [email protected] 89 Central Street, Houghton, 2198 P O Box 851, Houghton, 2041 www.straussart.co.za 1 Entrance gate to Keerweder 2 One way turn off for all vehicles 3 Collection of Purchases 4 Auction Marquee Registration & Catalogue Counter on Auction Day Refreshments & Lunch 5 The Homestead 6 Swimming Pool 7 Staircase to the Loft 8 The Dome Front Counter, Catalogue Sales & Pre-Registration during the Preview Bids Offi ce and Payments 9 Shuttle Parking Parking (Tuesday 22 & Wednesday 23 October, Collections Only) NO 10 Cloakrooms ENTRY 11 Disabled Parking Only Find your way 12 Lot 661 Korean carved stone fi gures 13 Lot 662 Japanese carved stone lantern around 4 NO ENTRY Keerweder 10 8 3 7 5 11 9 6 NO ENTRY 12 2 13 1 NO ENTRY Susan Sinek ©1999 Fine Art Auctioneers Consultants 1 2 PUBLIC AUCTION BY The Property of Keerweder (Pty) Ltd. Keerweder Fine Art Auctioneers Consultants Franschhoek, Western Cape Monday 22 October 2012 at 10am (Lots 1-225) 2.30pm (Lots 226-436) 5.30pm (Lots 437-662) VENUE Keerweder, Franschhoek PREVIEW Friday 19 October 10 to 5pm Saturday 20 October 10 to 5pm Sunday 21 October 10 to 5pm ENQUIRIES, CATALOGUES & BIDS OFFICE +27 (0) 21 683 6560 / 078 044 8185 SPECIALISTS IN CHARGE OF THIS SALE Vanessa Phillips, Ann Palmer & Kirsty Rich ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE R120.00, BROWSE THE FULL CATALOGUE ON www.straussart.co.za DIRECTORS: E BRADLEY (CHAIRMAN), ALL LOTS ARE SOLD SUBJECT TO THE CONDITIONS OF BUSINESS PRINTED AT THE BACK OF THIS CATALOGUE V PHILLIPS, B GENOVESE, A PALMER, CB STRAUSS AND SA WELZ (MD) OPPOSITE: VIEW OF THE VOORKAMER It is an honour for Strauss & Co to be entrusted with this significant sale.