Regeneration in Neighbourhood Plans Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portland Neighbourhood Plan: 1St Consultation Version Nov 2017

Neighbourhood Plan for Portland 2017-2031 1st Consultation Version Portland Town Council November 2017 Date of versions: 1st consultation draft November 2017 Pre-submission version Submission version Approved version (made) Cover photograph © Kabel Photography 1 Portland Neighbourhood Plan 1st Consultation Version Contents: Topic: page: Foreword 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Portland Now 5 3 The Strategic Planning Context 7 4 Purpose of the Neighbourhood Plan 12 5 The Structure of Our Plan 14 6 Vision, Aims and Objectives 15 7 Environment 18 8 Business and Employment 36 9 Housing 43 10 Transport 49 11 Shopping and Services 54 12 Community Recreation 58 13 Sustainable Tourism 67 14 Monitoring the Neighbourhood Plan 77 Glossary 78 Maps in this report are reproduced under the Public Sector Mapping Agreement © Crown copyright [and database rights] (2014) OS license 100054902 2 Foreword The Portland Neighbourhood Plan has been some time in preparation. Portland presents a complex and unique set of circumstances that needs very careful consideration and planning. We are grateful that the Localism Act 2012 has provided the community with the opportunity to get involved in that planning and to put in place a Neighbourhood Plan that must be acknowledged by developers. We must adhere to national planning policy and conform to the strategic policies of the West Dorset, Weymouth and Portland Local Plan. Beyond that, we are free to set the land use policies that we feel are necessary. Over the past three years much research, several surveys, lots of consultation and considerable discussion has been carried out by a working group of local people. -

Green Flag Management Spaces for Gardens

Introduction This document details the management of Green Flag gardens in Weymouth & Portland with the overall aim of maintaining and improving, where required, the quality of the gardens in terms of both physical features and the psychological benefits people gain from them. Historically there were three management plans and during the life time of the plans significant resources were used in an overhaul of the Green Flag gardens. The Council is now focused on a period of refinement in line with emerging needs. To do this, it is necessary to consider how the gardens fit within the priorities and policies of the Local Authority and to see how they are used and valued by the local and wider communities. Weymouth & Portland Borough Council has chosen to focus on the Green Flag Award as a means of raising and maintaining the standards of green spaces within the borough. The structure of this document follows Green Flag criteria. The shared aspects of garden management aims are: • To promote the application of Green Flag standards across the borough thereby raising standards overall. • To streamline the Green Flag Award application process in order to maximise resources available for consultation and the implementation of garden improvements. • To enable, as a result, an increase in the number of green spaces that Weymouth & Portland Borough Council can put forward for a Green Flag Award. Supporting Information For the purpose of the Green Flag desk top evaluation, an evidence folder containing further background information will be provided on the day of the site visit. The folder will contain information relating to operations, improvements, events, etc. -

Evidence Report 2014

(A Neighbourhood Plan for Portland, Dorset) Evidence Report April 2014 2 Portland Neighbourhood Plan Evidence Report Contents: Topic Sections: page: Introduction 3 Natural Environment & Built Environment 4 People & Housing 38 Business & Employment 60 Roads & Transport 90 Community & Social Facilities 102 Leisure & Recreation 118 Arts, Culture & Tourism 132 Appendix A 152 © Portland Town Council, 2014 Portland Neighbourhood Plan Evidence Report April 2014 3 Introduction Purpose Planning policy and proposals need to be based on a proper understanding of the place they relate to, if they are to be relevant, realistic and address local issues effectively. It is important that the Neighbourhood Plan is based on robust information and analysis of the local area; this is called the ‘evidence base’. Unless policy is based on firm evidence and proper community engagement, then it is more likely to reflect the assumptions and prejudices of those writing it than to reflect the needs of the wider area and community. We are advised that “the evidence base needs to be proportionate to the size of the neighbourhood area and scope and detail of the Neighbourhood Plan. Other factors such as the status of the current and emerging Local Plan policies will influence the depth and breadth of evidence needed. It is important to remember that the evidence base needs to reflect the fact that the plan being produced here will have statutory status and be used to decide planning applications in the neighbourhood area. It is necessary to develop a clear understanding of the neighbourhood area and policy issues covered; but not to review every piece of research and data in existence – careful selection is needed.”1 The evidence base for the Portland Neighbourhood plan comprises the many reports, documents and papers we have gathered (these are all listed in Appendix A, and are made available for reference via the Neighbourhood Plan website. -

FESTIVAL GUIDE 2021 PORTLAND, DORSET 2 One Thousand Ideas

B-SIDE.ORG.UK #BSIDE21 @bsidefest 09-12 SEPTEMBER FESTIVAL GUIDE 2021 PORTLAND, DORSET 2 One thousand ideas One amazing island 4 Said the sun to the moon Said the head to the heart "We have more in common Than sets us apart" - Lemn Sissay Photographer: Brendan Buesnel 6 WE ARE PROUD TO ANNOUNCE PENNSYLVANIA CASTLE ESTATE AS OUR B-SIDE CORE SPONSOR. Pennsylvania Castle Estate cannot work in isolation from what is happening around us. Colonial Leisure, owners of the Estate, believe that businesses can work sustainably in a way that supports our commercial goals and staff while achieving positive change in the local community and environment. Great words, but what does it look like in practice? For many years we have had goals to contribute to the environment, community, heritage, and culture on the Island. This is through a range of programmes which are Island centric. Some examples would be; the partnership with Portland Museum to develop the Church Ope Trail, the rollout of solar power and electric car chargers, sustainable management of our valuable trees, and working with community groups. We have been very proud of our support of the Islands rich culture. While we have held outdoor cinemas and theatres, it's b-side that we most look forward to supporting b-side understands the potential of the relationship between businesses and the arts as a powerful change agent. For the Estate the festival brings together those elements of environment, community, heritage, and culture in one place. The Estate team is committed to assisting b-side to continue to be a big feature of Island culture for years to come. -

Appendix 2: Portland Asset List

Appendix 2: Portland Asset List Site Name Asset Type TF Ref Number Grove Road Allotments Allotments WPBC-ALL005-01 Easton Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR005-01 Fortuneswell Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR006-01 Hambro Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR009-01 Lord Clyde Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR013-01 Masonic Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR015-01 New Ground Car Park Car Parks (Council Owned) WPBC-CAR032-06 Telescope located on land Catering & Retail WPBC-CAT011-01 opp Portland Heights Hotel St Johns Church Clock, Portland - NOT OWNED BY Clocks & Monuments WPBC-CAM017-01 WPBC Easton Gardens Clock Clocks & Monuments WPBC-PAR001-03 War Memorial, Victoria Clocks & Monuments WPBC-PAR006-08 Gardens Portland Cenotaph Yeates Clocks & Monuments WPBC-VAC047-02 Road Sidon War Memorial Yeates Clocks & Monuments WPBC-VAC047-03 Road Olympic Rings Yeates Road Clocks & Monuments WPBC-VAC047-04 Hardy House, Castle Road, Commercial WPBC-COM007-01 Portland Portland Cemetery, Weston Crematorium & Cemeteries WPBC-CEM006-01 Road Strangers Cemetery, Victory Crematorium & Cemeteries WPBC-CEM007-01 Road, Portland Fishermens Hut to the rear of Garages & Stores WPBC-STO006-01 119 Chiswell, Portland Fishing Hut to rear of Dolphin Cottage, 131 Brandy Row, Garages & Stores WPBC-STO007-01 Chiswell Store Huts adj 173 Chiswell & Garages & Stores WPBC-STO008 end of Brandy Row, Portland Islanders Club for Young People, East Weare Road, Halls WPBC-HAL005-01 Portland Access Road to 9 & 31 Court Barton, 9 Sharpitts, -

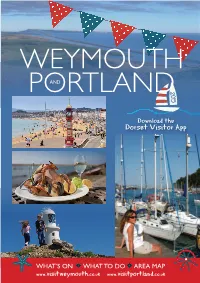

Dorset Visitor App

2015 Download the Dorset Visitor App WHAT’S ON WHAT TO DO AREA MAP www.visitweymouth.co.uk www.visitportland.co.uk The great place to be... ...for something relaxing and fun! You’re spoilt for choice for places to eat and drink outside, soaking up the atmosphere along the seafront. Widened pavements have created a Mediterranean style café culture or cross over to the boat styled boardwalked beach cafés which are open all year round. On your way, take a look at theSt. Alban sand Street sculptures in their specially designed shell shaped home, or the gleaming statues and Jubilee Clock. Stunning veils of artistic lighting gives the seafront a welcoming ambiance for your evening stroll. Floodlit tropical planting and colourful light columns brighten up the Esplanade, or look out to sea to view the atmospheric reflections of the bay. Getting to and around Weymouth and Portland has never been easier. Whether you are travelling by car, train or coach, Weymouth is an easy and acessible ‘Jurassic Stones’ sculpture Jubilee Clock holiday destination. There are also a host of cycle racks around the borough for your bike trips and adventures. Make your way to Portland, stopping off at the redeveloped Chesil Beach Centre, run by the Dorset Wildlife Trust. Don’t miss the Weymouth and Portland National Sailing Academy, home of the sailing for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, whilst visiting Portland Marina, Osprey Quay and Portland Castle Weymouth and Portland National Sailing Academy from Portland Weymouth Beach ‘Sand Weymouth Esplanade lighting Sculpture’ arena Portland Marina ...for something relaxing and fun! St. -

31621 Pcpspirit of Portland 2015 4Pp A5 LFT.Cdr

SATURDAY 1 AUGUST SUNDAY 2 AUGUST Jam on the Rock Skatefest Portland Museum Free Entry Day Chiswell Skatepark Wakeham. 10.30am to 4pm. See some of the best performers www.portlandmuseum.co.uk 24th July - 2nd August 2015 in the area. A Guided Tour of the World renowned Southwell Street Party Culverwell Mesolothic Site, Southwell 2pm to 6pm Portland Bill Road Lots of stalls and much more. Donations welcome 2pm to 4.30pm. www.portlandarchaeology.weeby.com Evening Entertainment Friday 24th July at the Eight Kings, Southwell Big Wild Chesil Event 6pm to 8pm. Chesil Beach Centre from 10am to 5pm. to Donations welcome. Sunday 2nd August 2015 www.chesilbeach.org For up to date information on the Spirit of Portland Festival Events at various locations please refer to the website throughout the Island. spiritofportlandfestival2015.wordpress.com or facebook page www.facebook.com/spiritofportlandfestival “A celebration of Portland’s unique heritage, All dates and times are correct at the time of press (June 2015). Events can be subject to change. culture and natural environment”. Please check details before travelling Full event details at: www.visit-dorset.com/whats-on spiritofportlandfestival2015.wordpress.com VISITOR INFORMATION There is a visitor centre at the Heights Hotel, Portland, DT5 2EN with details of events and shows, local attractions and public transport together with gift souvenirs and a coffee shop www.portlandtourism.co.uk email [email protected]. For a full list of Tourist Information Points throughout Weymouth and Portland go to www.visitweymouth.co.uk 24th July - 2nd August 2015 Supported by: EVENTS THROUGHOUT FRIDAY 24TH JULY SUNDAY 26TH JULY WEDNESDAY 29 JULY THE FESTIVAL Rotary Club Car Boot Sale Islanders Club for Young People Open Day Tescos Car Park, Easton from 9am. -

14 Pennsylvania Way, Portland, DT5 1FJ PROPERTY SUMMARY a Beautifully Presented Family Home, Spacious and Flexible

14 Pennsylvania Way, Portland, DT5 1FJ PROPERTY SUMMARY A beautifully presented family home, spacious and flexible. Energy efficient, features garage and parking, close to Portland Bill and Pennsylvania Castle. Current EPC Rating: 84 EPC B • Three Bedrooms • Well Presented • Town House • Garage • En Suite • Parking COMMENTARY Agent's Comment "An exceptional family home located opposite Pennsylvania Castle." £1,000 Per month Viewing Please contact Red House Estate Agents Tel: 01305 824455 PORTLAND - 01305 824455 HEAD OFFICE WEYMOUTH - 01305 824455 89/91 Fortuneswell, Portland DT5 1LY PROPERTY OVERVIEW Entrance Hall: Famed as the home of Olympic sailing, Weymouth and Portland is a coastal borough at the centre of Dorset's beautiful Jurassic Stairs to first floor. Doors to: coast. Central to the resort town of Weymouth is its picturesque harbour, Georgian seafront and child-friendly sandy beach. The Isle of Portland offers a more rugged coastline from Chesil Beach in the north to Portland Bill and the lighthouse at its far southern Kitchen/Dining Room: 4.37m x 3.78m (14'4" x 12'5") tip. Weymouth and the Isle of Portland are connected to the east-west A35 by the new A354 link road, while Weymouth's railway station has mainline services to London Waterloo. Range of fitted floor and wall storage units, work surfaces, integrated appliances, two front aspect windows. Utility Room: 1.70m x 1.57m (5'7" x 5'2") Deposits: Holding Deposit (per tenancy) Fitted floor, wall storage units, sink and drainer, built in washing machine and cupboard. One week's rent. This is to reserve a property. -

![Methodism in Portland [Electronic Resource]: and a Page of Church](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5695/methodism-in-portland-electronic-resource-and-a-page-of-church-3335695.webp)

Methodism in Portland [Electronic Resource]: and a Page of Church

METHODISM IN PORTLAND "A < J a o a 3 OS O o J c o o M e o o o Q <! « W METHODISM IN PORTLAND AND A PAGE OF CHURCH HISTORY BY ROBERT PEARCE CHARLES H. KELLY CASTLE ST., CITY RD. ; AND 26, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1898 PREFACE Some few years ago an attempt was made to establish a monthly magazine in connection with the Wesleyan Church at Portland, which it was hoped would have been of service to the Circuit. Owing to the difficulty of making it a financial success, it was only possible to continue its publi- cation for a few months. During its existence it contained one or two articles on the Introduction of Methodism into Portland, and these served to arouse in the minds of the Methodists of the island an interest in the approaching centenary of the event— the year 1891. In good time the question of its being suitably celebrated was brought before the Circuit Quarterly — vi PREFACE Meeting, and the friends of the Fortune's Well branch of the Circuit announced their inten- tion to celebrate the event by building a new chapel. It was also arranged to hold special services, and on Sunday, October 25 th, the Eev. John M'Kenny and the Eev. Josiah Jutsum preached in the Fortune's Well and Easton Chapels. On the following Monday evening a public meeting was held in the chapel at Fortune's Well, when Mr. Christopher Gibbs, the oldest local preacher on the Circuit plan, took the chair. Addresses were given by the Circuit ministers and others. -

Weymouth & Portland 2015 Celebrating A

Celebrating a great year WeymouthThe great place to be... & Portland 2015 of events and culture 21 Race to the Bill Triathlon 23 Weymouth Classic Triathlon - Bowleaze Cove. Come and share the wonderful spirit and uplifting WPNSA Weymouth Sprint Triathlon, 8am-12noon bustinskin.com experiences that are created in Weymouth and Portland annual events, featuring over 200 events 27-28 ASA SW Region Open 30 Dragon Boat Racing - Weymouth Beach and Bay embracing the area’s rich diversity of facilities and Water Swimming Championships Raising money for the Rotary Club natural environments. Preston Beach / Greenhill 30 & 31 Quayside Music From family festivals, sporting challenges, music, [email protected] and many art and craft shows. Festival - Weymouth Harbour 27 Canterbury Tales Presented rendezvousweymouth.co.uk by The Wessex Actors Company For the latest events news: www.visitweymouth.co.uk Nothe Fort nothefort.org.uk Please check details before travelling. September WPNSA = Weymouth & Portand National Sailing Academy 28 Jurassic Mini Car Club Display Weymouth Seafront, 10 am to 4 pm 2 Après Aquathon Series 7pm-8.30pm. Bowleaze Coveway, 28 It’s a Knockout - Lodmoor Park, Weymouth. 2 pm Weymouth bustinskin.com diverseabilitiesplus.org.uk 2 Dumble Bimble Run Starts from the YMCA, Reforne, April July Portland. 6.30pm. 5 mile and 2k fun run. Entry on the night only. rmpac.com 3-6 Easter weekend - Easter Fun, Egg hunts, Pirate Day, 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 Après Aquathon Series - bustinskin.com Easter Shopping, Pavilion Theatre Fairground & Hockey 3 National Merchant Navy Day - Flag Raising, Festival, activities throughout 4 National Trust Beach Picnic Weymouth Beach Civic Flag Pole, Council Offices, Weymouth. -

Geotechnical and Phase 11 Contamination Report

Suite 7, Westway Farm Business Park Wick Road, Bishop Sutton, Somerset BS39 5XP United Kingdom Tel: 01275 333036 www.integrale.uk.com Proposed Redevelopment Windmills Phase 4 Alm Place Portland DT5 1NH GE OTECHNICAL AND PHASE 11 CONTAMINATION RE PORT REPORT NO. 20065/A, February 2021 GEOLOGICAL • GEOTECHNICAL • ENVIRONMENTAL • ENGINEERING Intégrale is a trading name of Integrale Limited Registered Office: The Granary, Chewton Fields, Ston Easton, Somerset, BA3 4BX, United Kingdom Company Registration No. 2855366 England VAT Reg. No. 609 7402 37 Geotechnical and Phase II Contamination Report Proposed Redevelopment Windmills Phase 4 Alm Place Portland DT5 1NH Client: Betterment Properties [Weymouth] Limited Intégrale Report No. 20065/A, February 2021 Signature/Date Project Co-ordinator Phil Cresswell & Report Preparation: Mentor Consultant & Andrew Harris & Advice: Gareth Thomas Technical Director & Kay Boreland Report Approved: Final Check by: Phil Cresswell CONFIDENTIALITY STATEMENT This report is addressed to and may be relied upon by the following: Betterment Properties [Weymouth] Limited Unit 1, 2 Curtis Way Weymouth Dorset DT4 0TR Integrale Limited has prepared this report solely for the use of the client named above. Should any other parties wish to use or rely upon the contents of this report, written approval must be sought from Integrale Limited. An assignment fee may then be charged. GEOLOGICAL • GEOTECHNICAL • ENVIRONMENTAL • ENGINEERING Integrale Limited, Suite 7, Westway Farm Business Park, Wick Road, Bishop Sutton, Somerset, -

Map of Portland 35

SHOP SHOP DISCOVER SHOP 33 EAT EAT PORTLAND EAT SHOP A GREAT PLACE TO SHOP SHOP DRINK VISIT AND EXPLORE! 35 DRINK DRINK EAT EAT EAT SHOP STAY STAY SHOPSTAY SHOP DRINK 34 DRINK 47 WEYMOUTH & DRINK EAT PARTY PARTYENJOYEAPARTYTFor allENJOY yourEA Tvisitor information PORTLAND 2017ENJOY STAY STAY STAY A year of Adventure and Great Events Tourist Information Centre DRINK DRINK WALK DRINKWALK WALK PARTY PARTY PARTY The unique nature of the isle of Portland means that, while SLEEP it is connected to the mainland by a scenic causeway, it is SLEEPSAIL SLEEP the perfect escape from everyday hustle and bustle. SAIL SAIL WALK Made up of Chiswell, Fortuneswell, Castletown, Southwell WALK WALK and Easton, each area of this small island-just four and a PARTY half miles long and one and three quarter miles wide-has 33 43 PAWATCHRTY PARTY SHOP something different to offer. WATCH WATCH SHOPSAILSHOP Walkers revel in and around the island coast path. SAIL SAIL Take the scenic stretch leading to the most southerly point WALK SHOP of the island at Portland Bill, where you will see the famous June 17-23 WALK SHOP Weymouth and Portland armed forces day WDISCOVERALK SHOP EAT lighthouse and two lesser known lighthouses. DISCOVERDISCOVER EAT EAT celebrations WATCH Or you can walk along the old Portland railway from June 22-25 WATCH WATCH International canoe sailing championships Castletown to Fortuneswell and reward yourself with July 8-9 EAT Pommery Dorset seafood festival SAIL EAT breathtaking views of Chesil Beach from the Heights July 28-30 PLAY SAIL EAT DRINK RAF careers Weymouth beach volleyball classicPLAY SAIL DRINK End of July/August PLAY DRINKDISCOVER viewpoint after the steep climb.