Arxiv:Hep-Ph/9908260V2 26 Aug 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamentals of Particle Physics

Fundamentals of Par0cle Physics Particle Physics Masterclass Emmanuel Olaiya 1 The Universe u The universe is 15 billion years old u Around 150 billion galaxies (150,000,000,000) u Each galaxy has around 300 billion stars (300,000,000,000) u 150 billion x 300 billion stars (that is a lot of stars!) u That is a huge amount of material u That is an unimaginable amount of particles u How do we even begin to understand all of matter? 2 How many elementary particles does it take to describe the matter around us? 3 We can describe the material around us using just 3 particles . 3 Matter Particles +2/3 U Point like elementary particles that protons and neutrons are made from. Quarks Hence we can construct all nuclei using these two particles -1/3 d -1 Electrons orbit the nuclei and are help to e form molecules. These are also point like elementary particles Leptons We can build the world around us with these 3 particles. But how do they interact. To understand their interactions we have to introduce forces! Force carriers g1 g2 g3 g4 g5 g6 g7 g8 The gluon, of which there are 8 is the force carrier for nuclear forces Consider 2 forces: nuclear forces, and electromagnetism The photon, ie light is the force carrier when experiencing forces such and electricity and magnetism γ SOME FAMILAR THE ATOM PARTICLES ≈10-10m electron (-) 0.511 MeV A Fundamental (“pointlike”) Particle THE NUCLEUS proton (+) 938.3 MeV neutron (0) 939.6 MeV E=mc2. Einstein’s equation tells us mass and energy are equivalent Wave/Particle Duality (Quantum Mechanics) Einstein E -

Exploring the Spectrum of QCD Using a Space-Time Lattice

ExploringExploring thethe spectrumspectrum ofof QCDQCD usingusing aa spacespace--timetime latticelattice Colin Morningstar (Carnegie Mellon University) New Theoretical Tools for Nucleon Resonance Analysis Argonne National Laboratory August 31, 2005 August 31, 2005 Exploring spectrum (C. Morningstar) 1 OutlineOutline z spectroscopy is a powerful tool for distilling key degrees of freedom z calculating spectrum of QCD Æ introduction of space-time lattice spectrum determination requires extraction of excited-state energies discuss how to extract excited-state energies from Monte Carlo estimates of correlation functions in Euclidean lattice field theory z applications: Yang-Mills glueballs heavy-quark hybrid mesons baryon and meson spectrum (work in progress) August 31, 2005 Exploring spectrum (C. Morningstar) 2 MonteMonte CarloCarlo methodmethod withwith spacespace--timetime latticelattice z introduction of space-time lattice allows Monte Carlo evaluation of path integrals needed to extract spectrum from QCD Lagrangian LQCD Lagrangian of hadron spectrum, QCD structure, transitions z tool to search for better ways of calculating in gauge theories what dominates the path integrals? (instantons, center vortices,…) construction of effective field theory of glue? (strings,…) August 31, 2005 Exploring spectrum (C. Morningstar) 3 EnergiesEnergies fromfrom correlationcorrelation functionsfunctions z stationary state energies can be extracted from asymptotic decay rate of temporal correlations of the fields (in the imaginary time formalism) Ht −Ht z evolution in Heisenberg picture φ ( t ) = e φ ( 0 ) e ( H = Hamiltonian) z spectral representation of a simple correlation function assume transfer matrix, ignore temporal boundary conditions focus only on one time ordering insert complete set of 0 φφ(te) (0) 0 = ∑ 0 Htφ(0) e−Ht nnφ(0) 0 energy eigenstates n (discrete and continuous) 2 −−()EEnn00t −−()EEt ==∑∑neφ(0) 0 Ane nn z extract A 1 and E 1 − E 0 as t → ∞ (assuming 0 φ ( 0 ) 0 = 0 and 1 φ ( 0 ) 0 ≠ 0) August 31, 2005 Exploring spectrum (C. -

Three Lectures on Meson Mixing and CKM Phenomenology

Three Lectures on Meson Mixing and CKM phenomenology Ulrich Nierste Institut f¨ur Theoretische Teilchenphysik Universit¨at Karlsruhe Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, D-76128 Karlsruhe, Germany I give an introduction to the theory of meson-antimeson mixing, aiming at students who plan to work at a flavour physics experiment or intend to do associated theoretical studies. I derive the formulae for the time evolution of a neutral meson system and show how the mass and width differences among the neutral meson eigenstates and the CP phase in mixing are calculated in the Standard Model. Special emphasis is laid on CP violation, which is covered in detail for K−K mixing, Bd−Bd mixing and Bs−Bs mixing. I explain the constraints on the apex (ρ, η) of the unitarity triangle implied by ǫK ,∆MBd ,∆MBd /∆MBs and various mixing-induced CP asymmetries such as aCP(Bd → J/ψKshort)(t). The impact of a future measurement of CP violation in flavour-specific Bd decays is also shown. 1 First lecture: A big-brush picture 1.1 Mesons, quarks and box diagrams The neutral K, D, Bd and Bs mesons are the only hadrons which mix with their antiparticles. These meson states are flavour eigenstates and the corresponding antimesons K, D, Bd and Bs have opposite flavour quantum numbers: K sd, D cu, B bd, B bs, ∼ ∼ d ∼ s ∼ K sd, D cu, B bd, B bs, (1) ∼ ∼ d ∼ s ∼ Here for example “Bs bs” means that the Bs meson has the same flavour quantum numbers as the quark pair (b,s), i.e.∼ the beauty and strangeness quantum numbers are B = 1 and S = 1, respectively. -

Quark Masses 1 66

66. Quark masses 1 66. Quark Masses Updated August 2019 by A.V. Manohar (UC, San Diego), L.P. Lellouch (CNRS & Aix-Marseille U.), and R.M. Barnett (LBNL). 66.1. Introduction This note discusses some of the theoretical issues relevant for the determination of quark masses, which are fundamental parameters of the Standard Model of particle physics. Unlike the leptons, quarks are confined inside hadrons and are not observed as physical particles. Quark masses therefore cannot be measured directly, but must be determined indirectly through their influence on hadronic properties. Although one often speaks loosely of quark masses as one would of the mass of the electron or muon, any quantitative statement about the value of a quark mass must make careful reference to the particular theoretical framework that is used to define it. It is important to keep this scheme dependence in mind when using the quark mass values tabulated in the data listings. Historically, the first determinations of quark masses were performed using quark models. These are usually called constituent quark masses and are of order 350MeV for the u and d quarks. Constituent quark masses model the effects of dynamical chiral symmetry breaking discussed below, and are not directly related to the quark mass parameters mq of the QCD Lagrangian of Eq. (66.1). The resulting masses only make sense in the limited context of a particular quark model, and cannot be related to the quark mass parameters, mq, of the Standard Model. In order to discuss quark masses at a fundamental level, definitions based on quantum field theory must be used, and the purpose of this note is to discuss these definitions and the corresponding determinations of the values of the masses. -

Higgs Bosons with Large Couplings to Light Quarks

YITP-SB-19-25 Higgs bosons with large couplings to light quarks Daniel Egana-Ugrinovic1;2, Samuel Homiller1;3 and Patrick Meade1 1C. N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794, USA 2Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 2Y5, Canada 3Department of Physics, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York 11973, USA Abstract A common lore has arisen that beyond the Standard Model (BSM) particles, which can be searched for at current and proposed experiments, should have flavorless or mostly third-generation interactions with Standard Model quarks. This theoretical bias severely limits the exploration of BSM phenomenology, and is especially con- straining for extended Higgs sectors. Such limitations can be avoided in the context of Spontaneous Flavor Violation (SFV), a robust and UV complete framework that allows for significant couplings to any up or down-type quark, while suppressing flavor- changing neutral currents via flavor alignment. In this work we study the theory and phenomenology of extended SFV Higgs sectors with large couplings to any quark generation. We perform a comprehensive analysis of flavor and collider constraints of extended SFV Higgs sectors, and demonstrate that new Higgs bosons with large arXiv:1908.11376v2 [hep-ph] 31 Dec 2019 couplings to the light quarks may be found at the electroweak scale. In particular, we find that new Higgses as light as 100 GeV with order ∼ 0.1 couplings to first- or second-generation quarks, which are copiously produced at the LHC via quark fusion, are allowed by current constraints. Furthermore, the additional SFV Higgses can mix with the SM Higgs, providing strong theory motivation for an experimental program looking for deviations in the light quark{Higgs couplings. -

The 21St-Century Electron Microscope for the Study of the Fundamental Structure of Matter

The Electron-Ion Collider The 21st-Century Electron Microscope for the Study of the Fundamental Structure of Matter 60 ) milner mit physics annual 2020 by Richard G. Milner The Electron-Ion Collider he Fundamental Structure of Matter T Fundamental, curiosity-driven science is funded by developed societies in large part because it is one of the best investments in the future. For example, the study of the fundamental structure of matter over about two centuries underpins modern human civilization. There is a continual cycle of discovery, understanding and application leading to further discovery. The timescales can be long. For example, Maxwell’s equations developed in the mid-nineteenth century to describe simple electrical and magnetic laboratory experiments of that time are the basis for twenty-first century communications. Fundamental experiments by nuclear physicists in the mid-twentieth century to understand spin gave rise to the common medical diagnostic tool, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Quantum mechanics, developed about a century ago to describe atomic systems, now is viewed as having great potential for realizing more effective twenty-first century computers. mit physics annual 2020 milner ( 61 u c t g up quark charm quark top quark gluon d s b γ down quark strange quark bottom quark photon ve vμ vτ W electron neutrino muon neutrino tau neutrino W boson e μ τ Z electron muon tau Z boson Einstein H + Gravity Higgs boson figure 1 THE STANDARD MODEL (SM) , whose fundamental constituents are shown sche- Left: Schematic illustration [1] of the fundamental matically in Figure 1, represents an enormous intellectual human achievement. -

Flavor Symmetries and Fermion Masses }

LBL-35586; UCB-PTH-94/10 April 1994 Flavor symmetries and fermion masses } Andrija Rasin 2 Ph. D. Dissertation Department of Physics, University of California, k '•keley, CA 94720 and Theoretical Physics Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory University of California, Berkeley, CA 9J, 720 Abstract We introduce several ways in which approximate flavo; ymmetries act on fermions and which are consistent with observed fermion masses and mixings. Flavor changing interactions mediated by new scalars appear as a consequence of approximate flavor symmetries. We discuss the experimental limits on masses of the new scalars, and show that the masses can easily be of the order of weak scale. Some implications for neutrino physics are also discussed. Such flavor changing interactions would easily erase any primordial baryon asymmetry. We show that this situation can be saved by simply adding a new charged particle with its own asymmetry. The neutral ity of the Universe, together with sphaleron processes, then ensures a survival of baryon asymmetry. Several topics on flavor structure of the supersymmetric grand uni fied theories are discussed. First, we show that the successful predic tions for the Kobayashi-Maskawa mixing matrix elements, V^/V^ = i , . Jm^/mc and Vtd/Vu = Jm,ilm„ are a consequence of a large class of models, rather than specific properties of a few models. Second, we discuss how the recent observation of the decay b —» 57 constrains the parameter space when the ratio of the vacuum expectation values of the two Higgs doublets, tan/?, is large. Finally, we discuss the flavor structure of proton decay. We observe a surprising enhancement of the branching ratio for the muon mode in SO(10) models compared to the same mode in the SU(5) model. -

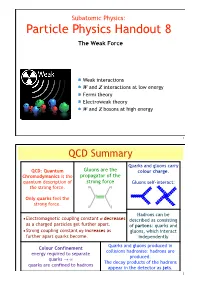

Particle Physics Handout 8 the Weak Force

Subatomic Physics: Particle Physics Handout 8 The Weak Force Weak interactions W and Z interactions at low energy Fermi theory Electroweak theory W and Z bosons at high energy 6 6 SELF-INTERASELF-INTERACTIONSCTIONS hhhljkhsdlkh 1 At this point, QCDhhhljkhsdlkhlooks like a stronger version of QED. At this point, QCD looks like a stronger version of QED. This is true up to a point. However, in practice QCD This is true up to a point. However, in practice QCD behaves very differently to QED. The similarities arise from behaves very differently to QED. The similarities arise from QCD Summarythe fact that both involve the exchange of MASSLESS the fact that both involve the exchange of MASSLESS spin-1 bosons. The big difference is that GLUONS carry spin-1 bosons. The big difference is that GLUONS carry colour “cQuarksharge”. and gluons carry QCD: Quantum Gluonscolour are“c theharg e”. colour charge. GLUONS CAN INTERACT WITH OTHER GLUONS: Chromodymanics is the propagatorGLUONS of theCAN INTERACT WITH OTHER GLUONS: quantum description of strong force Gluons self-interact:g g the strong force. g gg g g Only quarks feel the g g g strong force. g gg g 3 GLUON VERTEX 4 GLUON VERTEX 3 GLUON VERTEX 4 GLUON VERTEX Hadrons can be Electromagnetic coupling constant ! decreasesEXAMPLE: Gluon-Gluon Scattering • EXAMPLE: Gluon-GluondescribedScattering as consisting as a charged particles get further apart. of partons: quarks and •Strong coupling constant !S increases as gluons, which interact + + further apart quarks become. + independently+ Quarks and gluons produced in Colour Confinement collisions hadronise: hadrons are energy required to separate produced. -

Classification of Elementary Particles

CLASSIFICATION OF ELEMENTARY PARTICLES #Classification On the basis of “SPIN”: - •Elementary Particles are categorised in two classes i.e. Bosons and Fermions: - BOSONS Introduction: In particle physics boson is the type of particle that obeys the rule of Bose- Einstein statistics. These bosons have quantum spin having integral value 0, +1, -1, +2, -2, etc. •History: The name Boson comes from the surname of Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose and physicist Albert Einstein. They develop a method of analysis called Bose-Einstein Statistics. In an effort to understand the Plank's law, Bose proposed a method to analyse the behaviour of photon in 1924.He sent paper to Einstein. One of the most dramatic effect of Bose- Einstein Statistics is the prediction that boson can overlap and coexist with other bosons. Because of this it is possible to become a photon to laser. The name Boson First coined by scientists Paul Dirac in the honour of famous scientists Satyendra Nath Bose and Albert Einstein. Regarding: •Boson are fundamental particle such as gluons ,W ,Z boson, recently discovered Higgs boson aka God particle and Graviton. •Boson may be elementary like Photon or Composite i.e.made with two or more elementary particle. •All observed particles are either fermion or Boson. Types of Bosons- •Bosons are categorised into two categories; Gauge Boson: Gauge Boson are the particle that Carries the interaction of fundamental forces between particles. All known Gauge Boson have spin 1 and therefore all Gauge Boson are vector. •gauge boson is characterized into 5 categories. •Gluons(g): That carries strong nuclear forces between matter particle. -

The Quark Model and Deep Inelastic Scattering

The quark model and deep inelastic scattering Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Pions . 2 1.2 Baryon number conservation . 3 1.3 Delta baryons . 3 2 Linear Accelerators 4 3 Symmetries 5 3.1 Baryons . 5 3.2 Mesons . 6 3.3 Quark flow diagrams . 7 3.4 Strangeness . 8 3.5 Pseudoscalar octet . 9 3.6 Baryon octet . 9 4 Colour 10 5 Heavier quarks 13 6 Charmonium 14 7 Hadron decays 16 Appendices 18 .A Isospin x 18 .B Discovery of the Omega x 19 1 The quark model and deep inelastic scattering 1 Symmetry, patterns and substructure The proton and the neutron have rather similar masses. They are distinguished from 2 one another by at least their different electromagnetic interactions, since the proton mp = 938:3 MeV=c is charged, while the neutron is electrically neutral, but they have identical properties 2 mn = 939:6 MeV=c under the strong interaction. This provokes the question as to whether the proton and neutron might have some sort of common substructure. The substructure hypothesis can be investigated by searching for other similar patterns of multiplets of particles. There exists a zoo of other strongly-interacting particles. Exotic particles are ob- served coming from the upper atmosphere in cosmic rays. They can also be created in the labortatory, provided that we can create beams of sufficient energy. The Quark Model allows us to apply a classification to those many strongly interacting states, and to understand the constituents from which they are made. 1.1 Pions The lightest strongly interacting particles are the pions (π). -

![Arxiv:1802.04248V1 [Hep-Lat] 12 Feb 2018 12Department of Physics, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 13244, USA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0638/arxiv-1802-04248v1-hep-lat-12-feb-2018-12department-of-physics-syracuse-university-syracuse-new-york-13244-usa-3090638.webp)

Arxiv:1802.04248V1 [Hep-Lat] 12 Feb 2018 12Department of Physics, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 13244, USA

FERMILAB-PUB-17/492-T TUM-EFT 107/18 Up-, down-, strange-, charm-, and bottom-quark masses from four-flavor lattice QCD A. Bazavov,1 C. Bernard,2, ∗ N. Brambilla,3, 4, y N. Brown,2 C. DeTar,5 A.X. El-Khadra,6, 7 E. G´amiz,8 Steven Gottlieb,9 U.M. Heller,10 J. Komijani,3, 4, 11, z A.S. Kronfeld,7, 4, x J. Laiho,12 P.B. Mackenzie,7 E.T. Neil,13, 14 J.N. Simone,7 R.L. Sugar,15 D. Toussaint,16, { A. Vairo,3, ∗∗ and R.S. Van de Water7 (Fermilab Lattice, MILC, and TUMQCD Collaborations) 1Department of Computational Mathematics, Science and Engineering, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA 2Department of Physics, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA 3Physik-Department, Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen,85748 Garching, Germany 4Institute for Advanced Study, Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen,85748 Garching, Germany 5Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, USA 6Department of Physics, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA 7Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, Illinois 60510, USA 8CAFPE and Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica y del Cosmos, Universidad de Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain 9Department of Physics, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405, USA 10American Physical Society, One Research Road, Ridge, New York 11961, USA 11School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom arXiv:1802.04248v1 [hep-lat] 12 Feb 2018 12Department of Physics, Syracuse University, -

Standard Model of Particle Physics Problem Set

The Big Idea All matter is composed of fundamental building blocks, called particles. These building blocks are much smaller than an atom, and so are sometimes referred to as subatomic particles. Particles interact with one another according to a set of rules. Sometimes particles interact by exchanging other particles. The set of particles and interactions we believe to exist is called the Standard Model. We know that this model is not complete, but it is as much as we know today. The fifth of the five conservation laws is called CPT symmetry. The law states that if you reverse the spatial coordinates of a particle, change it from matter to anti-matter, and reverse it in time the new object is now indistinguishable from the original. Matter • Particles can be grouped into two camps: fermions and bosons. Typically matter is made up of fermions, while interactions (which lead to forces of nature such as gravity and electromagnetic) occur through the exchange of particles called bosons. (There are exceptions to this.) Electrons and protons are fermions, while photons (light particles) are bosons. • Fermions (matter particles) can be broken into two groups: leptons and quarks. Each of these groups comes in three families. • The first family of leptons consists of the electron and the electron neutrino. The second family consists of the muon and the muon neutrino. The third consists of the tau and the tau neutrino. Particles in each successive family are more massive than the family before it. • The first family of quarks consists of the up and down quark.