Magna Carta for Hswm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Gaps” and the Possible Abolition of Consensual Stop and Search

“Legislative gaps” and the possible abolition of consensual stop and search James Chalmers, University of Glasgow 24 June 2015 1. I have been asked to provide a note for the Independent Advisory Group on Stop and Search on the legislative gaps which might be left if consensual stop and search were abolished in Scotland. That note follows. I should note that it has been prepared in a very short timescale and is not intended to represent an authoritative or exhaustive review of the relevant law or principles, but I hope that it is of some assistance to the Group. Background 2. At common law, the police may search the person of anyone they have lawfully arrested. Beyond this, however, there is (except in cases of urgency) no common law power of search. The principle remains that set out by the Lord Justice-General (Inglis) in Jackson v Stevenson (1897) 2 Adam 255 at 260: ...a constable is entitled to arrest, without a warrant, any person seen by him committing a [crime], and he may arrest on the direct information of eye witnesses. Having arrested him, I have no doubt that the constable could search him. But it is a totally different matter to search a man in order to find evidence to determine whether you will apprehend him or not. If the search succeeds... you will apprehend him; but if the search does not succeed, you will not apprehend him. Now, I have only to say that I know of no authority for ascribing to constables the right to make such tentative searches, and they seem contrary to constitutional principle. -

The European Union Withdrawal (Consequential Modifications) (Eu Exit) Regulations 2020

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE EUROPEAN UNION WITHDRAWAL (CONSEQUENTIAL MODIFICATIONS) (EU EXIT) REGULATIONS 2020 2020 No. [XXXX] 1. Introduction 1.1 This explanatory memorandum has been prepared by the Cabinet Office and is laid before Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. 1.2 This memorandum contains information for the Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments. 2. Purpose of the instrument 2.1 The purpose of this instrument is to ensure that the UK statute book works coherently and effectively following the end of the transition period. 2.2 It clarifies how certain terms, including EU-related definitions, should be interpreted in domestic legislation on or after IP completion day. As part of this, the instrument clarifies how cross references to EU legislation should be read. 2.3 The instrument makes technical repeals to redundant provisions within primary legislation arising from the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (“EUWA”). These are primarily repeals of amending provisions, in particular relating to the European Communities Act 1972 (“the ECA”), where EUWA has already provided for the repeal of the amended provisions. The purpose of the repeals in these Regulations is to tidy up the statute book and they have no substantive effect. 2.4 The instrument amends the Interpretation Act 1978 (and the devolved equivalents) in relation to the interpretation of references to “relevant separation agreement law” . The instrument also amends EUWA to provide for how existing references to EU instruments that form part of relevant separation agreement law and how existing non- ambulatory references to direct EU legislation should be read. It also makes consequential amendments to the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (Consequential Modifications and Repeals and Revocations) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 1(S.I. -

Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2015

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2015. (See end of Document for details) Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2015 CHAPTER 9 JUSTICE ACT (NORTHERN IRELAND) 2015 PART 1 SINGLE JURISDICTION FOR COUNTY COURTS AND MAGISTRATES' COURTS 1. Single jurisdiction: abolition of county court divisions and petty sessions districts 2. Administrative court divisions 3. Directions as to distribution of business 4. Lay magistrates 5. Justices of the peace 6. Consequential amendments PART 2 COMMITTAL FOR TRIAL CHAPTER 1 RESTRICTION ON HOLDING OF PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS AND MIXED COMMITTALS 7. Preliminary investigations 8. Mixed committals: evidence on oath at preliminary inquiry Document Generated: 2021-08-12 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2015. (See end of Document for details) CHAPTER 2 DIRECT COMMITTAL FOR TRIAL IN CERTAIN CASES Application of this Chapter 9. Application of this Chapter Direct committal for trial: guilty pleas 10. Direct committal: indication of intention to plead guilty Direct committal for trial: specified offences 11. Direct committal: specified offences Direct committal for trial: offences related to specified offences 12. Direct committal: offences related to specified offences Direct committal for trial: procedures 13. Direct committal: procedures 14. Specified offences: application to dismiss 15. Restrictions on reporting applications for dismissal 16. Supplementary and consequential provisions PART 3 PROSECUTORIAL FINES Prosecutorial fine 17. Prosecutorial fine: notice of offer 18. Prosecutorial fine notice 19. Amount of prosecutorial fine 20. Restrictions on prosecutions Payment of prosecutorial fine 21. Payment of prosecutorial fine Non-payment of prosecutorial fine 22. -

General Conformity ______

MKC/26 _______________________________ GENERAL CONFORMITY ______________________________ A note on the meaning of the words “general conformity” in section 24 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004. 1. Words used in an Act of Parliament may be defined, in which case they mean what Parliament has attributed to them by way of meaning. However, many words used in an Act of Parliament are not defined, in which case they may be defined in the Interpretation Act 1978 or left undefined. The object in construing an Act of Parliament is to ascertain the intention of Parliament as expressed in the Act, considering it as a whole and in its context and acting on behalf of the people. 1 2. The words “general conformity” are not defined in either the 2004 Act or the Interpretation Act 1978. Accordingly, they have their ordinary English meaning and, given that the ordinary English meaning of words takes colour from their context, the words “general conformity” are to be considered in the context 2 of the Act. This, of course, reflects the last sentence of the preceding paragraph. 1 This sentence is taken from Halsbury’s Laws of England, 4 th edition Reissue, at volume 44(1), paragraph 372. The sentence in Halsbury’s Laws is supported by numerous cases starting with Heydon’s Case (1584) 3 Co Rep 7a at 7b. 2 The importance of context in law was emphasised in R. v. Secretary of State ex p. Daly [2001] UKHL 26, [2001] 3 All ER 433, [2001] 2 WLR 1622. Lord Steyn said “In law context is everything”. -

Statutory Instrument Practice

Statutory Instrument Practice A guide to help you prepare and publish Statutory Instruments and understand the Parliamentary procedures relating to them - 5th edition (November 2017) Statutory Instrument Practice Page i Statutory Instrument Practice is published by The National Archives © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to: [email protected]. Statutory Instrument Practice Page ii Preface This is the fifth edition of Statutory Instrument Practice (SIP) and replaces the edition published in November 2006. This edition has been prepared by the Legislation Services team at The National Archives. We will contact you regularly to make sure that this guide continues to meet your needs, and remains accurate. If you would like to suggest additional changes to us, please email them to the SI Registrar. Thank you to all of the contributors who helped us to update this edition. You can download SIP from: https://publishing.legislation.gov.uk/tools/uksi/si-drafting/si- practice. November 2017 Statutory Instrument Practice Page iii Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................. 3 CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... -

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru National

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru National Assembly for Wales Y Pwyllgor Materion Cyfansoddiadol a Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Deddfwriaethol Committee Bil deddfwriaeth (Cymru) Legislation (Wales) Bill CLA(5) LW05 Ymateb gan Keith Bush QC1 Evidence from Keith Bush QC Introductory 1. The Bill is divided into two substantive parts (Parts 1 and 2) which deal with distinct aspects of legislation, namely: The accessibility of Welsh law, including the fostering of a process of consolidation and codification; The interpretation of Welsh law by the enactment, in effect, of an Interpretation Act applying to Welsh legislation. 2. Given the distinct character of these two Parts each Part (together, in the case of Part 2, with the relevant provisions of Parts 3 and 4, which deal with matters ancillary to that Part) will be discussed separately. Accessibility of Welsh law (Part 1) 3. Part 1 of the Bill gives effect to the Welsh Government’s response to the Law Commission’s proposals “Form and Accessibility of the Law Applicable in Wales” (2016)2 by: Placing a statutory duty on the Counsel General to keep the accessibility of Welsh law under review; Placing a statutory duty on the Counsel General and the Welsh Government to prepare, for each term of the National Assembly, a programme setting out what they intend to do to improve the accessibiity of Welsh law, including their proposed activities intended to contribute to an ongoing process of consolidating and codifying Welsh law, maintaining its form and facilitating the use of the Welsh language. 1 See Appendix for the author’s cv. 2https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fil e/560239/57148_Law_Comm_366_V1_Eng_Web.pdf 4. -

Brexit: What Now? Uncoupling UK Law from the EU

Brexit: what now? Uncoupling UK law from the EU Much UK law is currently linked to that of the EU. Ending the UK’s membership of the EU will require significant uncoupling of the two legal systems. This paper provides an introduction to the inter-relationship of UK law and EU law and the legal mechanisms that might be used to separate them. As the issues surrounding implementation are highly complex, this introductory paper tries to provide a clear outline that can act as the foundation for more detailed analysis. The “ECA”: The European Communities Act 1972 – UK Membership – legal status the key UK statute implementing the UK’s UK law has historically taken the view that an membership of the EU. international treaty (or non-UK law ratified by the UK Government) does not form part of the domestic laws of the UK unless and until it is given effect by, or pursuant to, an Act of the UK Parliament. In limited circumstances, the UK Government can give effect to treaty obligations without specific legislation. The EU law perspective is that the obligations of EU law apply Categories of EU Law throughout the EU as an automatic consequence of EU law can be defined in the following membership of the EU. This means that EU law will, on principal categories: its own terms, no longer apply in the UK immediately after the UK stops being an EU Member State. As a – EU Treaties: The primary law of the EU. Binding result, the UK’s membership of the EU operates on on the UK as an EU Member State. -

The Local Authorities (Executive Arrangements) (Functions and Responsibilities) (Wales) Regulations 2007

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WALES STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2007 No. (W. ) LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WALES The Local Authorities (Executive Arrangements) (Functions and Responsibilities) (Wales) Regulations 2007 EXPLANATORY NOTE (This note is not part of the Regulations) Part II of the Local Government Act 2000 (“the 2000 Act”) provides for the discharge of a local authority’s functions by an executive of the authority (which must take one of the forms specified in section 11(2) to (5) of that Act) unless those functions are specified as functions that are not to be the responsibility of the authority’s executive. These regulations specify functions that are not to be the responsibility of an authority’s executive or are to be the responsibility of an executive only to a limited extent or only in specified circumstances. These regulations revoke the Local Authorities Executive Arrangements (Functions and Responsibilities) (Wales) Regulations 2001, the Local Authorities Executive Arrangements (Functions and Responsibilities) (Amendment) (Wales) Regulations 2002, the Local Authorities Executive Arrangements (Functions and Responsibilities) (Amendment) (Wales) Regulations 2003 and the Local Authorities Executive Arrangements (Functions and Responsibilities) (Amendment) (Wales) Regulations 2004 (“the 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004 Regulations”), consolidate the provisions of those regulations and make further provision. Regulations 3, 4, 5 and 6, by reference to the Schedules to the Regulations, set out the limitations on what functions may be exercised by an executive. Schedule 1 lists those functions which must not be exercised by an executive and Schedule 2 lists those functions which may be the responsibility of an authority’s executive, if the authority so decides. -

Office of the Parliamentary Counsel Drafting Guidance

OFFICE OF THE PARLIAMENTARY COUNSEL DRAFTING GUIDANCE __________________________________ Please send comments on the contents and suggestions for additions to the Drafting Techniques Group. 2 October 2010 FOREWORD Introduction 1 This guidance has been produced by the Drafting Techniques Group of the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel (“OPC”). 2 It is designed for members of OPC who are drafting Bills to be considered in Parliament. It is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to legislative drafting; nor is it a guide to statutory interpretation or past drafting practice. 3 Members of the OPC are asked to have regard to the guidance. But everything in the guidance is subject to the fundamental consideration that drafts must be accurate and effective, and it is recognised that drafters will need to take their particular requirements into account. It follows that there will be departures from what is said here. Overview 4 Part 1 deals with the general drafting principle of clarity. Drafters will need to think about clarity whenever and whatever they draft. Those new to drafting might like to read this Part in one go (and experienced drafters might like to re-read it occasionally). 5 The remaining Parts contain guidance on particular points which drafters are likely to come across. The intention is that these Parts will be referred to as and when necessary. 6 The need to achieve clarity does of course inform everything that is said in the remaining Parts. But there are other drafting principles which are relevant here too, such as effectiveness, consistency and conciseness. 7 Part 2 deals with some specific language-related points. -

Interpretation Act 1978, Cross Heading: Supplementary

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Interpretation Act 1978, Cross Heading: Supplementary. (See end of Document for details) Interpretation Act 1978 1978 CHAPTER 30 Supplementary 21 Interpretation etc. (1) In this Act “Act” includes a local and personal or private Act; and “subordinate legislation” means Orders in Council, orders, rules, regulations, schemes, warrants, byelaws and other instruments made or to be made under any Act [F1or made or to be made on or after [F2IP completion day under any retained direct EU legislation] other than retained direct EU CAP legislation as so defined][F3or made or to be made on or after exit day under retained direct EU CAP legislation as defined in section 2 of the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020]. (2) This Act binds the Crown. Textual Amendments F1 Words in s. 21(1) inserted (31.12.2020) by European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (c. 16), s. 25(4), Sch. 8 para. 19 (with s. 19, Sch. 7 para. 26, Sch. 8 para. 37) (as amended by S.I. 2020/463, regs. 1(1), 8); S.I. 2020/1622, reg. 3(n) F2 Words in s. 21(1) substituted (31.12.2020) by European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 (c. 1), s. 42(7), Sch. 5 para. 10 (with s. 38(3)) (as amended by S.I. 2020/463, regs. 1(1), 9); S.I. 2020/1622, reg. 5(j) F3 Words in s. 21(1) inserted (30.4.2020) by The Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020 (Consequential Amendments) Regulations 2020 (S.I. -

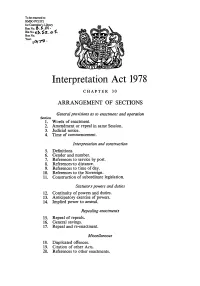

Interpretation Act 1978

To be returned to HMSO PC12C1 for Controller's Library Run No. a3.14 Bin No. O+Z , O 5. Box No. Year. lam - Interpretation Act 1978 CHAPTER 30 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS General provisions as to enactment and operation Section 1. Words of enactment. 2. Amendment or repeal in same Session. 3. Judicial notice. 4. Time of commencement. Interpretation and construction 5. Definitions. 6. Gender and number. 7. References to service by post. 8. References-to distance. 9. References to time of day. 10. References to the Sovereign. 11. Construction of subordinate legislation. Statutory powers and duties 12. Continuity of powers and duties. 13. Anticipatory exercise of powers. 14. Implied power to amend. Repealing enactments 15. Repeal of repeals. 16. General savings. V. Repeal and re-enactment. Miscellaneous 18. Duplicated offences. 19. Citation of other Acts. 20. References to other enactments. ii c. 30 Interpretation Act 1978 Supplementary Section 21. Interpretation etc. 22. Application to Acts and Measures. 23. Application to other instruments. 24. Application to Northern Ireland. 25. Repeals and savings. 26. Commencement. 27. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Words and expressions defined. Schedule 2-Application of Act to existing enactments. Part I-Acts. Part II-Subordinate legislation. Schedule 3-Enactments repealed. c. 30 1 ELIZABETH II Interpretation Act 1978 1978 CHAPTER 30 An Act to consolidate the Interpretation Act 1889 and certain other enactments relating to the construction and operation of Acts of Parliament and other instruments, with amendments to give effect to recommendations of the Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission. [20th July 1978] BB rr ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- General provisions as to enactment and operation 1. -

Imperial Laws Application Bill-98-1

IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL NOTE THIS Bill is being introduced in its present form so as to give notice of the legislation that it foreshadows to Parliament and to others whom it may concern, and to provide those who may be interested with an opportunity to make representations and suggestions in relation to the contemplated legislation at this early formative stage. It is not intended that the Bill should pass in its present form. Work towards completing and polishing the draft, and towards reviewing the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand, is proceeding under the auspices of the Law Reform Council. It is intended to introduce a revised Bill in due course, and to allow ample time for study of the revised Bill and making representations thereon. The enactment of a definitive statutory list of Imperial subordinate legis- lation in force in New Zealand is contemplated. This list could appropriately be included in the revised Bill, but this course is not intended to be followed if it is likely to cause appreciable delay. Provision for the additional list can be made by a separate Bill. Representations in relation to the present Bill may be made in accordance with the normal practice to the Clerk of the Statutes Revision Committee of tlie House of Representatives. No. 98-1 Price $2.40 IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL EXPLANATORY NOTE THIS Bill arises out of a review that is in process of being made by the Law Reform Council of the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand. The intention is that in due course the present Bill will be allowed to lapse, and a complete revised Bill will be introduced to take its place.