What Strategies Work for the Hard-To-Employ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Now Free Download Here Download Ebook

D2WXy (Free read ebook) Abundance Online [D2WXy.ebook] Abundance Pdf Free Beth Henley audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #123288 in Audible 2009-09-01Format: Original recordingOriginal language:EnglishRunning time: 103 minutes | File size: 38.Mb Beth Henley : Abundance before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Abundance: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Another HenleyBy P. B. HawkinsAll I can say is congratulations to Beth Henley! Henley won a Pulitzer for "Crimes of the Heart" which I have read and seen performed. I was underwhelmed by both experiences. As an audience member who has seen my share of theatrical performances, "Abundance" does not have near the staying power of "Crimes of the Heart". I very much appreciate southern writers, female southern writers in particular. Perhaps Henley is over my head and I just don't get it. If that is the case, I say touche'.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy ElizabethWomen struggle with dreams of love and adventure. Mythic.0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Fern RaganRead before I saw the play! Helped tremendously! I met the playwright! From the Pulitzer Prize winning author of Crimes of the Heart comes this poignant but unromanticized story of the hard lives of pioneers on the high plains of Wyoming in the 1860's. Macon and Bess are two mail-order brides, lured to the West by the promise of new beginnings through marriage to men they have never met. -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

David Rabe's Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast with F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perl

David Rabe’s Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast With F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perlman and More t2conline.com/david-rabes-good-for-otto-gets-star-studded-cast-with-f-murray-abraham-ed-harris-mark-linn-baker-amy- madigan-rhea-perlman-and-more/ Suzanna January 30, 2018 Bowling F. Murray Abraham (Barnard), Kate Buddeke (Jane), Laura Esterman (Mrs. Garland), Nancy Giles (Marci), Lily Gladstone (Denise), Ed Harris (Dr. Michaels), Charlotte Hope (Mom), Mark Linn- Baker (Timothy), Amy Madigan (Evangeline), Rileigh McDonald (Frannie), Kenny Mellman (Jerome), Maulik Pancholy (Alex), Rhea Perlman (Nora) and Michael Rabe (Jimmy), will lite up the star in the New York premiere of David Rabe’s Good for Otto. Rhea Perlman took over the role of Nora, after Rosie O’Donnell, became ill. Directed by Scott Elliott, this production will play a limited Off-Broadway engagement February 20 – April 1, with Opening Night on Thursday, March 8 at The Pershing Square Signature Center (The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, 480 West 42nd Street). Through the microcosm of a rural Connecticut mental health center, Tony Award-winning playwright David Rabe conjures a whole American community on the edge. Like their patients and their families, Dr. Michaels (Ed Harris), his colleague Evangeline (Amy Madigan) and the clinic itself teeter between breakdown and survival, wielding dedication and humanity against the cunning, inventive adversary of mental illness, to hold onto the need to fight – and to live. Inspired by a real clinic, Rabe finds humor and compassion in a raft of richly drawn characters adrift in a society and a system stretched beyond capacity. -

Weekly Specials

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, May 11, 2004 5 abigail dustry. Little did I know that the let- sighted to expect all heavy-set remember the 1950s know what real as to why those sharp little hooks are Women tired ter would hit a nerve with so many women to be farsighted — or limber. torture is. That was the day of the always right in the dead center of our van buren women. My cup runneth over ... DEAR ABBY: I am very slender bullet-shaped bra! No wonder the backs. We know it’s to keep us gals Read on: and small-busted. Underwire bras first act of rebellion in the women’s from relaxing for even a minute. It’s of burden of DEAR ABBY: While you’re on hurt. Just try to find a 34-B that liberation movement was the burn- pretty hard to lean back and feel com- •dear abby the subject of bras, may I add my 2 doesn’t have underwires. — BRA- ing of bras. — RUTH L. IN FRESNO fortable with those little devils frac- bad bra design cents? I want to tell you how incon- LESS IN OKLAHOMA DEAR RUTH L.: We don’t have turing your spine! I’m sure I’m not DEAR ABBY: “Double-Jointed a woman is a 42-D (or more) and re- venient it is for large-sized women DEAR BRA-LESS: Do what I do. to look back to the ’50s to remember the only one complaining. — DIS- in Dayton,” who complained about quires a bra every waking moment, — 200 pounds — when our size is al- Emancipate yourself by using a ra- those bras; all we have to do is rent GUSTED CUSTOMER how difficult it is to buy a bra, she has a choice of — white. -

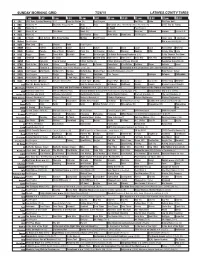

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Cast Biographies

CAST BIOGRAPHIES MICHAEL SHANNON (Gary Noesner) Academy Award®, Golden Globe® and Tony Award® nominated actor Michael Shannon continues to make his mark in entertainment, working with the industry's most respected talent and treading the boards in notable theaters around the world. Shannon will next be seen in Guillermo del Toro's The Shape of Water, a love story set against the backdrop of Cold War-era America. The film co-stars Sally Hawkins, Richard Jenkins, Michael Stuhlbarg and Octavia Spencer. Fox Searchlight will release the film December 2017. In 2018, Shannon will return to Red Orchard Theatre for its 25th Anniversary to direct the world premiere of Traitor, Brett Neveu's adaption of Henrik Ibsen's Enemy of the People. Traitor will include ensemble members Dado, Larry Grimm, Danny McCarthy, Guy Van Swearingen and Natalie West and will run from January 5, 2018 through February 25, 2018. Back on the big screen, Shannon will then be seen in the Nicolai Fuglsig’s 12 Strong opposite Chris Hemsworth. The project follows a team of CIA agents and special forces who head into Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in an attempt to dismantle the Taliban. Warner Brothers is releaseing the film in January 2018. Later next year, Shannon will also be seen in writer-director Elizabeth Chomko’s drama, What They Had, opposite Hilary Swank. The story centers on a woman who must fly back to her hometown when her Alzheimer's-stricken mother wanders into a blizzard and the return home forces her to confront her past, which includes her brother (Shannon). -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

Buried Child Debuts on Theater Close-Up Showcasing the Best of Off-Broadway & Regional Theater November 28 at 9 P.M

Press Contact: Harry Forbes 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-Winning Buried Child Debuts on Theater Close-Up Showcasing the Best of Off-Broadway & Regional Theater November 28 at 9 p.m. on THIRTEEN Ed Harris & Amy Madigan head acclaimed production from The New Group Theater Close-Up , the unique collaboration between THIRTEEN and the large community of New York City area non-profit Off-Broadway theaters, will present Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize- winning play Buried Child in Scott Elliott’s acclaimed production from The New Group, Monday, November 28 at 9 p.m. on THIRTEEN, with an encore presentation on Friday, December 2 at 3:30 a.m. The play will also air Sunday, December 18 at 10 p.m. on WLIW21. Actress Blythe Danner hosts the broadcast. This production features Ed Harris as Dodge, Amy Madigan as Halie, Rich Sommer and Paul Sparks as sons Bradley and Tilden, respectively, Nat Wolff as grandson Vince, Taissa Farmiga as Vince's girlfriend Shelly, and Larry Pine as Father Dewis. The play -- captured live on-stage during the March 30 BroadwayHD livestream-- was revived 20 years after its last major New York production. Dodge (Harris) and Halie (Madigan) are barely hanging on to their farmland and their sanity while looking after their two wayward grown sons (Sommer and Sparks). When their grandson Vince (Wolff) arrives with his girlfriend (Farmiga), no one seems to recognize him, and confusion abounds. As Vince tries to make sense of the chaos, the rest of the family dances around a deep, dark secret. -

FY2009 Annual Listing

2008 2009 Annual Listing Exhibitions PUBLICATIONS Acquisitions GIFTS TO THE ANNUAL FUND Membership SPECIAL PROJECTS Donors to the Collection 2008 2009 Exhibitions at MoMA Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at The Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London. Photo © Frederick Charles, fcharles.com Exhibitions at MoMA Book/Shelf Bernd and Hilla Becher: Home Delivery: Fabricating the Through July 7, 2008 Landscape/Typology Modern Dwelling Organized by Christophe Cherix, Through August 25, 2008 July 20–October 20, 2008 Curator, Department of Prints Organized by Peter Galassi, Chief Organized by Barry Bergdoll, The and Illustrated Books. Curator of Photography. Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Peter Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing Dalí: Painting and Film Christensen, Curatorial Assistant, Through July 7, 2008 Through September 15, 2008 Department of Architecture and Organized by Connie Butler, Organized by Jodi Hauptman, Design. The Robert Lehman Foundation Curator, Department of Drawings. Chief Curator of Drawings. Young Architects Program 2008 Jazz Score July 20–October 20, 2008 Multiplex: Directions in Art, Through September 17, 2008 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, 1970 to Now Organized by Ron Magliozzi, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Assistant Curator, and Joshua Design. Organized by Deborah Wye, Siegel, Associate Curator, The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Department of Film. Dreamland: Architectural Chief Curator of Prints and Experiments since the 1970s Illustrated Books. George Lois: The Esquire Covers July 23, 2008–March 16, 2009 Through March 31, 2009 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, Projects 87: Sigalit Landau Organized by Christian Larsen, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Curatorial Assistant, Research Design. -

Original Wile~ Rein & Fielding

ORIGINAL WILE~ REIN & FIELDING 1776 K STREET, N. W. WASHINGTON, O. c. 20006R~" "',"",,-~-.~ !,~ (202) 429-7000 .. DON NA COLEMAN GREGG J L"1'1. FACSIMILE (202) 429-7260 (202) 429-7049 July 18, 1997 Mr. William F. Caton, Secretary Federal Communications Commission 1919 M Street, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20554 Re: Notification Q/Permitted Ex Parte Presentation ion in MM Docket No. 95-176 Dear Mr. Caton: Lifetime Television ("Lifetime''), by its attorneys and pursuant to Section 1.206{a){I) of the Commission's rules, hereby submits an original and one copy ofa notification ofex parte contact in MM Docket No. 95-176. Nancy R. Alpert, Senior Vice President ofBusiness and Legal Affairs and Deputy General Counsel at Lifetime, Gwynne McConkey, Vice President ofNetwork Operations at Lifetime, along with Donna C. Gregg ofWiley, Rein & Fielding, met with Anita Wallgren, Legal Advisor to Commissioner Susan Ness, and Marsha MacBride, Legal Advisor to Commissioner James Quello, to discuss issues related to the above-cited docket and summarized in the written materials attached hereto. Kindly direct any questions regarding this matter to the undersigned counseL Respectfully submitted, \A \...!/~-u:t- Donna C. Gregg Counsel for Lifetime Television Enclosures Lifetime Closed Captioning - July 18, 1997 • Since it was established in 1984, Lifetime Television has become the premier network of "television for women." Lifetime currently reaches over 68 million households (over 90% of all cable homes) and is ranked fifth among all basic cable services in