The Gilund Project: Excavations in Regional Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2003) Paper Abstracts

Note: Abstracts exceeding the 150-word limit were abbreviated at approximately 175 words and marked with an ellipsis. Abraham, Shinu, University of Pennsylvania Modeling Social Complexity in Late Iron Age/Early Historic Tamilakam This paper evaluates social complexity of the South Indian region known as Tamilakam, comprising the states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu during the late Iron Age/Early Historic period. Tamilakam does not appear to conform to traditionally conceived forms of social organization, making it necessary to consider alternative models within which social complexity can be addressed through an analysis of material remains and their patterning. New mortuary, settlement, and ceramic data from a regional survey of the Palghat Gap in Kerala, South India, is considered and evaluated in the context of prevailing text-based reconstructions of the period. This approach for understanding early Tamil material culture does not ignore the historical record, but instead seeks to integrate the historical and archaeological records more tightly and explicitly. This study has been structured around the analysis of two bodies of material data--megaliths and ceramics--in conjunction with the analysis of historical documents, and concludes that the archaeological data from Iron Age/Early Historic Tamilakam can be better understand with the application of heterarchical principles to early Tamil society. Adamjee, Qamar, New York University Uniting Modernity and Tradition: The Art of Shahzia Sikander The scale, styles, superb draftsmanship and overall rich appearance of Shahzia Sikander’s paintings immediately recall some of the most memorable examples of Persian and Indian painting traditions from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Yet a closer look at the images reveals a far more complex dynamic, one deeply-rooted in contemporary issues and not simply a revival of traditional styles. -

Methods and Problems in the Site Census Approach: a View from Mewar Through Archaeology and Ethnohistory

Methods and Problems in the Site Census Approach: A View from Mewar through Archaeology and Ethnohistory Namita Sugandhi1, Teresa P. Raczek2, Prabodh Shirvalkar3, Charles K. Brummeler2 and Lalit Pandey4 1. Hartwick College, One Hartwick Drive, Oneonta, NY 13820, USA (Email: [email protected]) 2. Kennesaw State University, 402 Bartow Ave, Kennesaw, GA 30144, USA (Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) 3. Deccan College Post‐graduate and Research Institute, Yerwada, Pune –411006, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]) 4. J.R.N. Rajasthan Vidyapeeth University, Pratap Nagar, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 30October 2015; Accepted: 08November 2015; Revised: 22 November 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 163‐179 Abstract: The practice of conducting a regional census has some similarities but many differences from systematic archaeological survey. Both attempt to study “sites”, or material traces of human activities in the past, but the idea of an archaeological “census” utilizes a more informal approach to visiting sites that have been previously documented by earlier researchers. Archaeological census has the goal of assessing site destruction, degradation, and various issues associated with heritage management. The method can provide valuable data about the current status of sites and serve as an expedient tool for future research planning as well as in the development of community and cultural resource management strategies. In this paper, we present census details from a multi‐year project conducted in the Mewar Plain of Rajasthan, outlining our methods and the various conditions that shaped our approach and results, emphasizing in particular the role of ethnohistory. -

Immigrant Identity in the Indus Civilization: a Multi-Site Isotopic Mortuary Analysis

IMMIGRANT IDENTITY IN THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A MULTI-SITE ISOTOPIC MORTUARY ANALYSIS By BENJAMIN THOMAS VALENTINE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Benjamin Thomas Valentine 2 To Shannon 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Truly, I have stood on the shoulders of my betters to reach this point in my career. I could never have completed this dissertation without the unfailing support of my family, friends, and colleagues, both at home and abroad. I am grateful, most of all, for my wife, Shannon Chillingworth. I am humbled by the sacrifices she has made for dreams not her own. I can never repay her for the gifts she has given me, nor will she ever call my debt due. Shannon—thank you. I am likewise indebted to the scholars and institutions that have facilitated my graduate research these past eight years. Foremost among them is my faculty advisor, John Krigbaum, who took a chance on me, an aspiring researcher with little anthropological training, and welcomed me into the University of Florida (UF) Bone Chemistry Lab. I have worked hard not to fail him, as he has never failed me. Under John Krigbaum’s mentorship, I have earned my chance to succeed in academe. During my time at UF, I have benefited from the efforts of many excellent faculty members, but I am especially grateful to James Davidson, Department of Anthropology and George Kamenov and Jason Curtis, Department of Geological Sciences. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 709686.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 21-Feb-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 21-Feb-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE IN300394-13455837- Amount for unclaimed and A BASHKARAN NA 40 OLD MUNCHIFF COURT STREETINDIA Tamil Nadu 637001 10.00 21-Feb-2025 0000 unpaid dividend NO 198 ANUGRAHA -

Copper Technology in India : a Review

©.2001 NML Jamshedpur 831 007, India; Metollurgy in India: A Retrospective; (ISBN: 81-87053-56-7); Eds: P. Ramachandra Rao and N.G. Goswami; pp. 143-162. Prehistoric -Copper Technology in India : A Review D.P. Agrawal* ABSTRACT Copper has been used by mankind from 5" to 2nd Millennia BC. The paper traced how metal technology has been part of the reparative of the technologies pertaining to ceramics, stone industry, and even architecture. No doubt, the first use of copper must have been of native copper. With the growth of urbanization, especially of'the Indus civilization, the abundance of metal and technology advance progressed by leaps and bounds. The Archaeo-Metallurgical studies help a lot to know about typology of artifacts, technologies used, source of metal, what techniques ,different cultures used to make them artifact, mining technology? A lot remains to be done: relating ore bodies to the artifact, metallographic studies to known techniques of artifact making, alloying pattern minerals used, geochemistry of ore bodies to devise ways to fingerprint them through trace impurity patterns and lead isotope geochemistry etc. No less important are the ethno-archaeological studies to understand the man behind the technology and his artifact. A lot more can be achieved with the joint effort of metallurgical labs. and the archeologists. Key words : Ancient Indian copper technology, Archaco-metallurgi-Gd1 study, Ethno-archacological study, Pre-Harappan site. INTRODUCTION In the greater Indus region, it is clear that the origin and development of copper metal technology occurred in conjunction with developments in other technologies. The Neolithic and early Chalcolithic pyrotechnologies included the firing of clays to make pots, and the heating of stone materials to enhance colour, workability *Address : 10, familial Park, Bopal Road, Ahmedabad - 380058 143. -

Metals and Metallurgy in the Harappan Civilization

Indian Journal of History of Science, 53.3 (2018) 279-295 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i3/49460 Metals and Metallurgy in the Harappan Civilization Vibha Tripathi* (Received 27 February 2018) Abstract The Indus Valley also referred to as Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization excelled in variety of technologies, including metallurgy. Over the span of centuries, evolving from Pre/ Early Harappan to the Late Harappan cultural phases, the civilization evolved as an urban civilization. By the mature Harappan period (circa 2700 to 18/1700 BCE) metal technology attained great perfection. Several metallurgical innovations like the intricate ciré perdue or lost wax technique, true saw and the eye needle go to the credit of the metal smiths of that period. Exclusive objects of copper, gold, and silver came to be used. For special affects, minor metals like tin, arsenic, lead, antimony etc. came to be used for alloying. Although about 70% of the copper objects of the Harappan period are unalloyed, a judicious alloying pattern as per requirements may be discerned in the metal repertoire. Arsenic was found to be present in several statues probably with a specific reason. The sharp-edged cutting tools like razors, knives or daggers, arrowheads, spearheads, drills etc show a distinct alloying pattern with alloying of tin up to 12- 13%. The Harappan bronze tool repertoire comprised typical leaf-shaped arrowheads, spears with bent end, shaft-hole axe, double edged axes, the sword with amid-rib or the bronze female figurines like that of the ‘dancing girl’. In fashioning of pots and pans, technique of raising- sinking and drawing was employed. -

MTS – Candidates Called for Screening Test on 8-8-2021

1 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF AYURVEDA VACANCY NOTIFICATION NO. 1/2020 SCREENING TEST ON 8-8-2021 (SUNDAY) FROM 9 AM TO 10-30 AM FOR THE POSTS OF MULTI TASKING STAFF (M T S) A Screening Test to shortlist Candidates for Selection to the Post of MTS will be held on SUNDAY 8-8-2021 from 9-00 AM to 10-30 AM in the following Centres. Call Letters have been sent to the Candidates by Speed Post. The List of Candidates Called for Screening Test is given in the following Pages. The List of Applicatons rejected along with the reasons thereof, have also been posted on the Website. Candidates should report for the Screening Test at 8-00 AM at the alloted Centres and should bring the Call Letter and also Proof of Identity like Aadhar Card, Voter ID Card, Driving Licence etc. without which they will not be permitted to appear in the Test. It may be noted that conduct of the Screening Tests will be subject to any Order/Guideline on Covid-19 that may be imposed by State and/or Central Government. Candidades should follow all the Guidelines/Instructions regarding Covid-19. ,e-Vh-,l- inkas ij p;u gsrq NaVuh ijh{kk 8&8&2021 ¼jfookj½ dks fuEufyf[kr dsUnzkas ij vk;ksftr dh tk;sxhA vH;fFkZ;ksa dks ijh{kk gsrq cqykok i=@izos'k i= LihM ikLs V }kjk Hkst fn;s x;s gSA NaVuh ijh{kk gsrq cqyk;s x;s vH;fFkZ;ksa dh lwph vkxs i`"Bksa ij nh x;h gSA vLohd`r fd;s x;s vkosnu i=ka s dh lwph dkj.k lfgr laLFkku dh osc lkbZV ij iksLV dj nh x;h gSA vH;FkhZ mUg s vkoafVr ijh{kk dsUnz ij izkr% 7-00 cts fjikVs Z djsa rFkk ijh{kk grqs cqykok i=@izos'k i= yk;s rFkk igpku gsrq lcwr ;Fkk vk/kkj dkMZ] ernkrk igpku i=] MªkbZfoax ykbZlsUl lkFk yk;s vU;Fkk mUgs ijh{kk esa izfo"B gkus s dh vuqefr ugh nh tk;sxhA ;g Hkh /;ku dj ysosa fd NaVuh ijh{kk dk vk;kstu jkT;@dsUnz ljdkj }kjk le;≤ ij ykx w dksfoM&19 xkbZM ykbZu@vkns'kksa ds v/;k/khu gksxh ijh{kkfFkZ;ksa }kjk dksfoM+&19 ds lEcU/k esa tkjh fd;s x;s lHkh xkbZM ykbUl@fn'kk funZs'kksa dh ikyuk dh tkuh gksxhAs ROLL NO. -

The Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives ABC-CLIO’S Understanding Ancient Civilizations Series

The Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives ABC-CLIO’s Understanding Ancient Civilizations Series The Aztecs Ancient Canaan and Israel The Ancient Greeks The Ancient Maya Ancient Mesopotamia The Incas The Romans The Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives JANE R. McINTOSH Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McIntosh, Jane. The ancient Indus Valley : new perspectives / Jane McIntosh. p. cm. —(Understanding ancient civilizations series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-57607-908-9 (ebook) 1. Indus civilization. I. Title. DS425.M338 2008 934—dc22 2007025308 121110090812345678910 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Editorial Assistant: Sara Springer Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jed DeOrsay Media Resources Coordinator: Ellen Brenna Dougherty Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Manager: Paula Gerard ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an ebook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. This book is printed on acid-free paper ∞ Manufactured -

The Affect of Crafting Third Millennium BCE Copper Arrowheads from Ganeshwar, Rajasthan

The Affect of Crafting Third Millennium BCE Copper Arrowheads from Ganeshwar, Rajasthan Uzma Z. Rizvi Rivizi text.indd 1 20/09/2018 11:12:52 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-003-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-004-0 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and Uzma Z Rizvi 2018 Design by Asad Pervaiz All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Rizvi text.indd 2 24/09/2018 10:56:59 Table of Contents 8 List of Figures & Tables 10 Acknowledgements 13 Preface Part One Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four 16 Introduction to the 30 Contextualising 44 GJCC Material 58 The Affect of Affect of Crafting the Ganeshwar Culture and Crafting and Copper Corpus: Chronological Ancient Sociality 18 Crafting Theory: Archaeological Implications Thinking about the Practice and 59 Crafting Bodies Affect of Crafting 44 Material Culture of the Research 60 Labouring Places GJCC 18 The Affective Artefact: 31 Paleo-climate, Irrigation, 61 Crafting Complexity Objects of Colonial Desire 44 Ceramics and Subsistence and Objects of Science 62 Crafting Resonance Agriculture 47 Copper Artefacts 19 Technology and Crafting 64 Crafting Place 33 Ganeshwar Jodhpura 47 Arrowheads Style and Form: 65 -

District Census Handbook 9 Sikar, Part X a & X B, Series-18, Rajasthan

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN PARTS XA & XB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 9. SIKAR DISTRICT J V. 5. VERMA Of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan The motif on the cover is a montage presenting constructions typifying the rural and urban ..... set against a background formed by specimen Census notional maps of a urban aIId • rura. block. The drawing has been specially mada for us by Shri Paras BhansalL LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CeDeus ot ludia 1971-Series-18 Rajasthan i. being published iD the f'ollowiDg parts : GoremmeDt or IndJa Publicatloos Part I-A General Report. Part I-B An analysis of the demographic. social, cultural and migration patterns. Part I-C Subsidiary Tables. Part II-A General Population Tables. Part II-B Economic Tables. Part II-CCi) Distribution of Population, Mother Tongue and Religion. Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part n-C(ii) Other Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables. Tables on Household Composition, Single Year Age, Marital Status. Educational Levels. Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. etc., Bilingualism. Part III-A Report on Establishments. Part III-B Establishment Tables. Part IV Housing Report and Tables. Part V Special Tables and Notes on Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part VI-A Town Directory. Part VI-B Special Survey Report on Selected Towns. Part VI-C Survey Report on Selected Villages. Part VII Special Report on Graduate and Technical Personnel. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration. } • Part VIU-B Administration Report-Tabulation. For offiCial use only. Part IX Cenl!ius Atlas. Part IX-A Administrative Atlas. Govemment or Rajasthan PubileatiODII Part X-A&X-B District Census Hand Book-Town and Village Directory & Primary Census Abstract. -

Rejected Applications Received After 25.11.17 for The

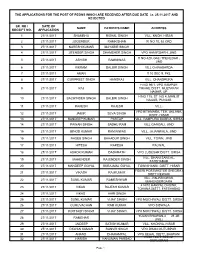

THE APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF PEONS WHICH ARE RECEIVED AFTER DUE DATE i.e. 25.11.2017 AND REJECTED SR. NO / DATE OF NAME FATHER'S NAME ADDRESS RECEIPT NO. APPLICATION 1 27/11/2017 SHAMBHU RISHAL SINGH VILL. KNOH, HISAR 2 27/11/2017 JOGENDER RAMKISHAN W NO 10, 52 CKD 3 27/11/2017 NARESH KUMAR MAYABIR SINGH 4 27/11/2017 JITENDER SINGH SHAMSHER SINGH VPO HAMIRGARH, JIND H NO 428, GALI THEKEDAR , 5 27/11/2017 ASHISH RAMNIWAS JIND 6 27/11/2017 VIKRAM DALBIR SINGH VILL CHINABARDA 7 27/11/2017 AMAN # 10 SEC 9, PKL 8 27/11/2017 GURPREET SINGH HANSRAJ VILL. CHANDPURA H NO 96/1, VPO RAMPUR 9 27/11/2017 RAJ TIRAHE DISTT. MUZAFFAR NAGAR, UP H NO 175, ST. NO 4, MANJIT 10 27/11/2017 BALWINDER SINGH BALBIR SINGH NAGAR, PUNJAB 11 27/11/2017 RAKESH RAJESH VILL. VPO BITHMARA, TEH. UKLANA, 12 27/11/2017 JAIBIR SEVA SINGH DISTT. HISAR 13 27/11/2017 SANDEEP KUMAR PARTAP VILL. RAMPURA BAGRIA, SIRSA 14 27/11/2017 PAWAN SINGH SADHU RAM VILL GANGALI, JIND 15 27/11/2017 BINOD KUMAR RAM NIWAS VILL. JAJANWALA, JIND 16 27/11/2017 NASEB SINGH BAHADUR SINGH VILL. TOWN, JIND 17 27/11/2017 HITESH RAKESH PALWAL 18 27/11/2017 ASHOK KUMAR DASHRATH VPO LUDESAR DISTT. SIRSA VILL. DHANI SANCHL, 19 27/11/2017 MAHENDER RAJENDER SINGH FATEHABAD 20 27/11/2017 MANDEEP GOYAL SURAJMAL GOYAL TOWN HANSI, DISTT. HISAR FIDERI POSTMASTER SHEORAJ 21 27/11/2017 VIKASH RAJKUMAR DISTT REWARI VILL JANJARIAWAS, 22 27/11/2017 SUNIL KUMAR RAMESHWAR MAHENDERGARH 414/10 HARPAL CHOWK, 23 27/11/2017 VIKAS RAJESH KUMAR TOHANA DISTT. -

Case of the Harappan Civilization

UNIT 5 ORIGINS OF AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL DOMESTICATION, CRAFT PRODUCTION TO URBANISATION (CASE OF THE HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION) Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Beginning of Food Production: Features 5.3 Why Did People Take Up Cultivation? 5.4 Earliest Farming Groups in the Indian Subcontinent 5.4.1 Mehrgarh: the Earliest Farming Village in the Indian Subcontinent 5.4.2 Expansion of the Agricultural Communities 5.4.3 Agriculture Spreads to the Indus Plains 5.4.4 Consequences of Agriculture 5.5 The Early Harappan Period 5.5.1 The Indus Region 5.5.2 The Lower Indus Plain 5.5.3 Intensification of Agriculture and Use of Copper 5.5.4 Planning of Settlements 5.6 Emergence of Cities 5.6.1 Population Increase and Shift 5.6.2 Warlike Conditions 5.6.3 Increase in the Size of Settlements 5.7 The Harappan civilization 5.7.1 Location of Settlements 5.7.2 Hierarchy of Settlements 5.7.3 Agriculture and Pastoralism in the Harappan Civilization 5.7.4 Town Planning 5.7.5 Craft Specialisation 5.7.6 Long Distance Trade 5.7.7 Decline of the Harappan Cities 5.8 Summary 5.9 Glossary 5.10 Exercises 5.11 Suggested Readings 5.1 INTRODUCTION The transition from foraging to farming is one of the turning points in human history. The seasonally mobile life of hunter-gatherers, who obtained their food from wild plants and animals, was replaced by the settled life of farmers, who cultivated crops and raised domesticated livestock. This shift from nomadic to sedentary life led to the growth of population and village settlement, the development of crafts such as pottery and metallurgy, and eventually to centralised city states and urbanization.