Field Guide to the I. G. S. Post-Symposium Tour, August 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 20, Tuam Author

Digital content from: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), no. 20, Tuam Author: J.A. Claffey Editors: Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie, Jacinta Prunty Consultant editor: J.H. Andrews Cartographic editor: Sarah Gearty Editorial assistants: Angela Murphy, Angela Byrne, Jennnifer Moore Printed and published in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2 Maps prepared in association with the Ordnance Survey Ireland and Land and Property Services Northern Ireland The contents of this digital edition of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 20, Tuam, is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Referencing the digital edition Please ensure that you acknowledge this resource, crediting this pdf following this example: Topographical information. In J.A. Claffey, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 20, Tuam. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2009 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 4 February 2016), text, pp 1–20. Acknowledgements (digital edition) Digitisation: Eneclann Ltd Digital editor: Anne Rosenbusch Original copyright: Royal Irish Academy Irish Historic Towns Atlas Digital Working Group: Sarah Gearty, Keith Lilley, Jennifer Moore, Rachel Murphy, Paul Walsh, Jacinta Prunty Digital Repository of Ireland: Rebecca Grant Royal Irish Academy IT Department: Wayne Aherne, Derek Cosgrave For further information, please visit www.ihta.ie TUAM View of R.C. cathedral, looking west, 1843 (Hall, iii, p. 413) TUAM Tuam is situated on the carboniferous limestone plain of north Galway, a the turbulent Viking Age8 and lends credence to the local tradition that ‘the westward extension of the central plain. It takes its name from a Bronze Age Danes’ plundered Tuam.9 Although the well has disappeared, the site is partly burial mound originally known as Tuaim dá Gualann. -

Crystal Reports

Bonneagar Iompair Éireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland 2020 National Roads Allocations Galway County Council Total of All Allocations: €28,848,266 Improvement National Primary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 17 N17GY_098 Claretuam, Tuam 5,000 Total National Primary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €5,000 Major Scheme 6 Galway City By-Pass 2,000,000 Total National Primary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 17 N17 Milltown to Gortnagunnad Realignment (Minor 2016) 600,000 Total National Primary - Minor Works: €600,000 National Secondary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 59 N59GY_295 Kentfield 100,000 63 N63GY RSI Implementation 100,000 65 N65GY RSI Implementation 50,000 67 N67GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY_010 Carrowmunnigh Road Widening 650,000 84 N84GY RSI Implementation 50,000 Total National Secondary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €1,050,000 Major Scheme 59 Clifden to Oughterard 1,000,000 59 Moycullen Bypass 1,000,000 Total National Secondary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 59 N59 Maam Cross to Bunnakill 10,000,000 59 N59 West of Letterfrack Widening (Minor 2016) 1,300,000 63 N63 Abbeyknockmoy to Annagh (Part of Gort/Tuam Residual Network) 600,000 63 N63 Liss to Abbey Realignment (Minor 2016) 250,000 65 N65 Kilmeen Cross 50,000 67 Ballinderreen to Kinvara Realignment Phase 2 4,000,000 84 Luimnagh Realignment Scheme 50,000 84 N84 Galway to Curraghmore 50,000 Total National Secondary - Minor Works: €16,300,000 Pavement HD28 NS Pavement Renewals 2020 -

Silver Strand Silverstrand Has a Safe, Shallow, Sandy Beach of Approximately 0.25Km Bounded on One Side by a Cliff and the Other by Rocks

Silver Strand Silverstrand has a safe, shallow, sandy beach of approximately 0.25km bounded on one side by a cliff and the other by rocks. It is particularly popular with and suitable for young families. It faces directly into Galway Bay giving spectacular views. There is a promenade with parking capacity for about 60 vehicles. It is suitable for swimming at low tide but the beach is largely covered during high tides. It is lifeguarded during the summer months. Blue Flag standard (2005). Barna Golf and Country Club Corbally, Barna, Co. Galway Telephone: +353 91 592677 Fax: +353 91 592674 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bearnagolfclub.com Located approx. 8km from Galway, and 3km north of Bearna village, this golf course is set in typical rugged Connemara countryside with fairways constructed between rocks and heather. The course was designed to suit all abilities. Bearna golf course is already being hailed as one of Ireland's finest. The inspired creativity of its designer R.J. Browne in the siting of tees and sand-based greens in the celebrated beauty of West of Ireland's Connemara landscape has produced a course of glamorously porportioned holes. Water comes into play at thirteen of the eighteen holes, each one boasting unique features which together test the golfer's total repertoire of skills. The final holes especially provide a spectacular finish to a satisfying and memorable experience. Caddy hire available. Dress code is neat & casual. Full canteen facilities available with full bar menu and restaurant. Course designed by Robert J Browne. Course length (m): 6174 Athenry Golf Club Palmerstown, Oranmore, Co. -

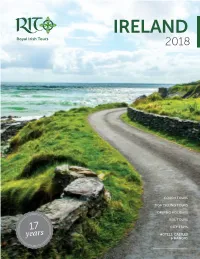

2018 CELEBRATING 17 Years

2018 CELEBRATING 17 years Canadian The authentic Irish roots One name, Company, Irish experience, run deep four spectacular Irish Heritage created with care. at RIT. destinations. Welcome to our We can recommend Though Canada is As we open tours 17th year of making our tours to you home for the Duffy to new regions memories in Ireland because we’ve family, Ireland is of the British Isles with you. experienced in our blood. This and beyond, our It’s been our genuine them ourselves. patriotic love is the priority is that we pleasure to invite you We’ve explored the driving force behind don’t forget where to experience Ireland magnificent basalt everything we do. we came from. up close and personal, columns at the We pride ourselves For this reason, and we’re proud Giant’s Causeway and on the unparalleled, we’ve rolled all of the part we’ve breathed the coastal personal experiences of our tours in played in helping to air at the mighty that we make possible under the name create thousands of Cliffs of Moher. through our strong of RIT. Under this exceptional vacations. We’ve experienced familiarity with the banner, we are As our business has the warm, inviting land and its locals. proud to present grown during this atmosphere of a The care we have for you with your 2018 time, the fundamental Dublin pub and Ireland will be evident vacation options. purpose of RIT has immersed ourselves throughout every Happy travels! remained the same: to in the rich mythology detail of your tour. -

John Redmond's Speech in Tuam, December 1914

Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha Template cover sheet which must be included at the front of all projects Title of project: John Redmond’s Speech in Tuam, December 1914 its origins and effect. Category for which you wish to be entered (i.e. Revolution in Ireland, Ireland and World War 1, Women’s history or a Local/Regional category Ireland and World War 1 Name(s) of class / group of students / individual student submitting the project Rang a 6 School roll number (this should be provided if possible) 20061I School type (primary or post-primary) Primary School name and address (this must be provided even for projects submitted by a group of pupils or an individual pupil): Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha Tír an Chóir Tuaim Contae na Gaillimhe Class teacher’s name (this must be provided both for projects submitted by a group of pupils or an individual pupil): Cathal Ó Conaire Teacher’s contact phone number: 0879831239 Teacher’s contact email address [email protected] Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha John Redmond’s Speech in Tuam, December 1914 its origins and effect. On December 7th 1914, the leader of the Irish Home Rule party, John Redmond, arrived in Tuam to speak to members of the Irish Volunteers. A few weeks before in August Britain had declared war on Germany and Redmond had in September (in a speech in Woodenbridge, Co Wexford) urged the Irish Volunteers to join the British Army: ‘Go on drilling and make yourself efficient for the work, and then account for yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends in defence of right, of freedom and religion in this war.’ He now arrived in Tuam by train to speak to the Volunteers there and to encourage them to do the same. -

Tropical Ice Core Records of Changes in Symmetry, Position And/Or Intensity of the Hadley Circulation on Milankovich, Millennial, and Centennial Time Scales

Tropical ice core records of changes in symmetry, position and/or intensity of the Hadley Circulation on Milankovich, millennial, and centennial time scales. Lonnie G. Thompson, Mary E. Davis, Ellen S. Mosley_Thompson, Tracy A. Mashiotta, and Ping-nan Lin Ice core records from South America, Africa, the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau provide evidence of past changes in position and intensity of the Hadley circulation. Cores from seven sites at elevations greater than 5600 m asl suggest that the climate (temperature and precipitation) from either side of the equator is out of phase. These records are combined with more than 120 other paleoclimate records to produce a global map of effective moisture changes between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and the Early Holocene (EH). The global pattern of changes in the tropical hydrological system between these two periods has been zonally symmetrical; for example, the zonal belts in the deep tropics that experienced greater aridity during the LGM attained maximum humidity in the EH, while at the same time the humid subtropical and mid- latitude belts generally became drier. In this paper we examine the spatial symmetry and asymmetry of these changes about the equator through time. A strong role for the Hadley circulation is suggested such that its position, its intensity, or both were altered as the Earth moved from glacial to interglacial conditions. The ice core records from these low-latitude, high-elevation sites also raise questions about; (1) the synchroneity of glaciation, (2) the relative importance of temperature and precipitation in governing the growth and decay of ice fields north and south of the equator, and; (3) the relative role that the strength and position of the Hadley circulation plays in determining the geographical distribution of low latitude ice fields. -

Galway County Development Plan 2022-2028

Draft Galway County Development Plan 2022- 2028 Webinar: 30th June 2021 Presented by: Forward Planning Policy Section Galway County Council What is County Development Plan Demographics of County Galway Contents of the Plan Process and Timelines How to get involved Demographics of County Galway 2016 Population 179,048. This was a 2.2% increase on 2011 census-175,124 County Galway is situated in the Northern Western Regional Area (NWRA). The other counties in this region are Mayo, Roscommon, Leitrim, Sligo, Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan Tuam, Ballinasloe, Oranmore, Athenry and Loughrea are the largest towns in the county Some of our towns are serviced by Motorways(M6/M17/M18) and Rail Network (Dublin-Galway, Limerick-Galway) What is County Development Plan? Framework that guides the future development of a County over the next six-year period Ensure that there is enough lands zoned in the County to meet future housing, economic and social needs Policy objectives to ensure appropriate development that happens in the right place with consideration of the environment and cultural and natural heritage. Hierarchy of Plans Process and Timelines How to get involved Visit Website-https://consult.galway.ie/ Attend Webinar View a hard copy of the plan, make a appointment to review the documents in the Planning Department, Áras an Chontae, Prospect Hill, Galway Make a Submission Contents of Draft Plan Volume 1 Written Statement-15 Chapters with Policy Objectives Volume 2 Settlement Plans- Metropolitan Plan, Small Growth Towns and Small -

Ilulissat Icefjord

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1149.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ilulissat Icefjord DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: DENMARK CRITERIA: N (i) (iii) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (i): The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of a stage in the Earth’s history: the last ice age of the Quaternary Period. The ice-stream is one of the fastest (19m per day) and most active in the world. Its annual calving of over 35 cu. km of ice accounts for 10% of the production of all Greenland calf ice, more than any other glacier outside Antarctica. The glacier has been the object of scientific attention for 250 years and, along with its relative ease of accessibility, has significantly added to the understanding of ice-cap glaciology, climate change and related geomorphic processes. Criterion (iii): The combination of a huge ice sheet and a fast moving glacial ice-stream calving into a fjord covered by icebergs is a phenomenon only seen in Greenland and Antarctica. Ilulissat offers both scientists and visitors easy access for close view of the calving glacier front as it cascades down from the ice sheet and into the ice-choked fjord. The wild and highly scenic combination of rock, ice and sea, along with the dramatic sounds produced by the moving ice, combine to present a memorable natural spectacle. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Located on the west coast of Greenland, 250-km north of the Arctic Circle, Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord (40,240-ha) is the sea mouth of Sermeq Kujalleq, one of the few glaciers through which the Greenland ice cap reaches the sea. -

School Age Services

School Age Services Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type of Service John Sweeney Park Afterschool, Carlow Regional 48 John Sweeney Park Carlow Carlow Lisa Hutton 059 9168008 Afterschool Youth Service Cill an Oir Afterschool, Carlow Regional Youth 32 Cill an Oir Graiguecullen Carlow Lisa Hutton 059 9164757 Afterschool Service Bailieborough Development St Annes Community Chapel Road Bailieborough Cavan Peader Reynolds 042 9694716 Afterschool Laragh Childcare Services Laragh Parish Hall Laragh Stradone Cavan Marianne Cosgrove 049 4323862 Afterschool Ennis CBS Afterschool New Road Lifford Ennis Clare Maura Coughlan 065 6841205 Afterschool MaryK's Childcare and Community Centre Deerpark Doora Ennis Clare Mary Kennedy 065 6868575 Afterschool Aftercare Scoil na Mainistreach Busy Bees Afterschool Club New Line Road Quin Clare Jill Morris 065 6825003 Afterschool Quin Dangan Teach na nog kidz Ltd Coopers Park Tulla Tulla Clare Carina Roseingrave 085 2200048 Afterschool Sherpa Kids Ballinspittle Ballinspittle National Ballinspittle Cork Teresa Bebb David Bebb 02 14773193 Afterschool National School School Sherpa Kids Ballygarvan Ballygarvan National Ballygarvan Cork Teresa Bebb David Bebb 02 14773193 Afterschool National School School Hairy Henry Ballylickey Bantry Cork Sandra Schmid 087 9389867 Afterschool After School Club Cloghroe National Cloghroe Blarney Cork Yvonne Kelly 021 4385573 Afterschool Sherpa Kids Gaelscoil Sheanlower Blarney Cork Emma Keane 021 4516874 Afterschool -

Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park “Work House: Apotoki Oyis - Education for Life” A Glacier National Park Science and Indian Education Program Glacier National Park P.O. Box 128 West Glacier, MT 59936 www.nps.gov/glac/ Produced by the Division of Interpretation and Education Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Revised 2015 Cover Artwork by Chris Daley, St. Ignatius School Student, 1992 This project was made possible thanks to support from the Glacier National Park Conservancy P.O. Box 1696 Columbia Falls, MT 59912 www.glacier.org 2 Education National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the assistance of many people over the past few years. The Appendices contain the original list of contributors from the 1992 edition. Noted here are the teachers and tribal members who participated in multi-day teacher workshops to review the lessons, answer questions about background information and provide additional resources. Tony Incashola (CSKT) pointed me in the right direc- tion for using the St. Mary Visitor Center Exhibit information. Vernon Finley presented training sessions to park staff and assisted with the lan- guage translations. Darnell and Smoky Rides-At-The-Door also conducted trainings for our education staff. Thank you to the seasonal education staff for their patience with my work on this and for their review of the mate- rial. -

Canadian Volcanoes, Based on Recent Seismic Activity; There Are Over 200 Geological Young Volcanic Centres

Volcanoes of Canada 1 V4 C.J. Hickson and M. Ulmi, Jan. 3, 2006 • Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Where do volcanoes occur? Driving forces • Volcano chemistry and eruption types • Volcanic Hazards Pyroclastic flows and surges Lava flows Ash fall (tephra) Lahars/Debris Flows Debris Avalanches Volcanic Gases • Anatomy of an Eruption – Mt. St. Helens • Volcanoes of Canada Stikine volcanic belt Presentation Outline Anahim volcanic belt Wells Gray – Clearwater volcanic field 2 Garibaldi volcanic belt • USA volcanoes – Cascade Magmatic Arc V4 Volcanoes in Our Backyard Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics In Canada, British Columbia and Yukon are the host to a vast wealth of volcanic 3 landforms. V4 How many active volcanoes are there on Earth? • Erupting now about 20 • Each year 50-70 • Each decade about 160 • Historical eruptions about 550 Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics • Holocene eruptions (last 10,000 years) about 1500 Although none of Canada’s volcanoes are erupting now, they have been active as recently as a couple of 4 hundred years ago. V4 The Earth’s Beginning Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 5 V4 The Earth’s Beginning These global forces have created, mountain Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics ranges, continents and oceans. 6 V4 continental crust ic ocean crust mantle Where do volcanoes occur? Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 7 V4 Driving Forces: Moving Plates Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 8 V4 Driving Forces: Subduction Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 9 V4 Driving Forces: Hot Spots Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 10 V4 Driving Forces: Rifting Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Ocean plates moving apart create new crust. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips.