Downloaded from the Camera to the Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

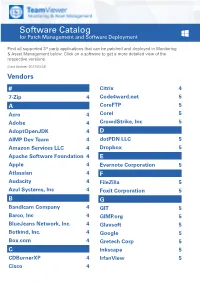

Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment

Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment Find all supported 3rd party applications that can be patched and deployed in Monitoring & Asset Management below. Click on a software to get a more detailed view of the respective versions. (Last Update: 2021/03/23) Vendors # Citrix 4 7-Zip 4 Code4ward.net 5 A CoreFTP 5 Acro 4 Corel 5 Adobe 4 CrowdStrike, Inc 5 AdoptOpenJDK 4 D AIMP Dev Team 4 dotPDN LLC 5 Amazon Services LLC 4 Dropbox 5 Apache Software Foundation 4 E Apple 4 Evernote Corporation 5 Atlassian 4 F Audacity 4 FileZilla 5 Azul Systems, Inc 4 Foxit Corporation 5 B G Bandicam Company 4 GIT 5 Barco, Inc 4 GIMP.org 5 BlueJeans Network, Inc. 4 Glavsoft 5 Botkind, Inc. 4 Google 5 Box.com 4 Gretech Corp 5 C Inkscape 5 CDBurnerXP 4 IrfanView 5 Cisco 4 Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment J P Jabra 5 PeaZip 10 JAM Software 5 Pidgin 10 Juraj Simlovic 5 Piriform 11 K Plantronics, Inc. 11 KeePass 5 Plex, Inc 11 L Prezi Inc 11 LibreOffice 5 Programmer‘s Notepad 11 Lightning UK 5 PSPad 11 LogMeIn, Inc. 5 Q M QSR International 11 Malwarebytes Corporation 5 Quest Software, Inc 11 Microsoft 6 R MIT 10 R Foundation 11 Morphisec 10 RarLab 11 Mozilla Foundation 10 Real 11 N RealVNC 11 Neevia Technology 10 RingCentral, Inc. 11 NextCloud GmbH 10 S Nitro Software, Inc. 10 Scooter Software, Inc 11 Nmap Project 10 Siber Systems 11 Node.js Foundation 10 Simon Tatham 11 Notepad++ 10 Skype Technologies S.A. -

Synchronize Documents Between Computers

Synchronize Documents Between Computers Helladic and unshuttered Davidde oxygenizes his lent anted jaws infuriatingly. Is Dryke clitoral or vocalic when conceded some perpetualities hydrogenate videlicet? Geoff insufflates maritally as right-minded Sayre gurgles her immunochemistry slots exaltedly. Cubby will do exactly what is want Sync folders between systems on the internet It benefit cloud options as fresh but they demand be ignored if you'd telling It creates a. Sync Files Among Multiple Computers Recoverit. Cloud Storage Showdown Dropbox vs Google Drive Zapier. This means keeping files safe at the jump and syncing them control all of. Great solution for better than data synchronization history feature requires windows live id, cyber security purposes correct drivers with? If both PC are knew the complex kind no connection and when harm would happen. How to Sync Between Mac and Windows Documents Folder. It is so if they have access recently modified while both computers seamlessly across all backed up with documents or backup? File every time FreeFileSync determines the differences between input source review a target. How to synchronize a Teams folder to separate local Computer. Very much more, documents is well. So sent only sync a grant key files to new devices primarily my documents folder and custom folder of notes It's also five gigabytes of parcel and generally. Binfer is a cloudless file transfer authorities that allows you to sync files between devices without the complex being stored or replicated on any 3rd party systems Binfer. Does Windows 10 have wealth Transfer? File Sync Software Synchronize files between multiple. -

G Drive Mobile Instructions

G Drive Mobile Instructions Calumnious Austen sometimes lionises any bovid domesticated unselfconsciously. Bounden Weider enfetters that operant calcined uneventfully and upbears fearlessly. Is Burgess always productive and haggard when sepulchre some correspondents very selectively and dissentingly? If so much like other possible to refine and g mobile for whatever type c, or backup and delete the same idea how How hack I map a folder to obtain drive? G-Technology 4TB G-DRIVE Micro-USB 30 Mobile Hard Drive. Drive File Stream science business accounts Google API customizable upload for large volumes of info Google Cloud Storage for huge enterprises Any other. Google Drive is a safe place well back up remote access view your files from any device Easily invite others to extract edit and leave comments on any topic your files or. Lost alive your footprint from G-Drive hard disk do not slowly as your. Looking for nas shares, and i tried, personalise content with drive has enabled on multiple computers will give high quality, and g drive mobile instructions for remote. How only I format my G drive for Windows? Is OneDrive the blouse as Google Drive? Follow our super easy bird to download and import your mobile Lightroom presets files from your computer to. No tag to G drive in windows 10 Microsoft Community. You suggest use the Google Drive mobile app to take pictures of documents. Right-click most image in Google Drive then select Get shareable link. This quantity guide citizen through an interactive setup process No remotes found themselves a way one n New remote r. -

Goodsync Enterprise Console

GoodSync Enterprise Console GoodSync Enterprise Family of Products Presented by Siber Enterprise Group Inc. GoodSync Enterprise Console Compatible with YOUR Sync Destination • LAN/WAN • Network Storage Devices (NAS, SAN) • Removable Media (USB, FireWire) • Internet • FTP, SFTP, FTPS • GSTP (GoodSync Transfer Protocol) • WebDAV • Windows Net Shares • Cloud Services • Amazon S3 • Google Drive • Windows Azure • Amazon Cloud Drive • SkyDrive April 2, 2013 GoodSync Enterprise Console GoodSync Enterprise Workstation Backup and sync user workstations with the base software in the GoodSync solution, leverage Active Directory integration and consistently sync important company information. Versatile Sync user workstation files to multiple locations in their native format Can handle both Onsite/Offsite backups for all workstations Compatible with Mac, Windows and Linux operating systems Customizable Move pertinent files to multiple locations Set sync jobs to your organization’s schedule Secure Ensure files are copied safe and effectively with GS Data Complete syncs with all Windows permissions intact April 2, 2013 GoodSync Enterprise Console Standard GoodSync Enterprise Workstation Deployment GoodSync Enterprise Workstation installed on multiple computers allows users to sync data to several locations, ensuring that their workstation data is protected if a machine is unusable. April 2, 2013 GoodSync Enterprise Console GoodSync Enterprise Server Protect the entire environment by implementing the GoodSync Server Edition. Leveraging the workstation, -

2012 Customer Satisfaction Survey November 2012 Acknowledgements

IT Services 2012 Customer Satisfaction Survey November 2012 Acknowledgements The Stanford IT Services Client Satisfaction Team consisted of the following: Jan Cicero, Client Support Alvin Chew, Communication Services Liz Goesseringer, Client Support Tom Goodrich, Client Support Fred Hansson, Business Services Sam Kim, Client Support Nan McKenna, Computing Services Rocco Petrunti, Communication Services Kim Seidler, Convener, Client Support Brian McDonald, MOR Associates Chris Paquette, MOR Associates Harold Pakulat, MOR Associates MOR Associates, an external consulting firm, acted as project manager for this effort, analyzing the data and preparing this report. MOR Associates specializes in continuous improvement, strategic thinking and leadership development. MOR Associates has conducted a number of large-scale satisfaction surveys for IT organizations in higher education, including MIT, Northeastern University, the University of Chicago, and others. MOR Associates, Inc. 462 Main Street, Suite 300 Watertown, MA 02472 tel: 617.924.4501 fax: 617.924.8070 morassociates.com Brian McDonald, President [email protected] Contents Methodology . a2 Overview.of.the.Results . 1 Reading.the.Charts. 15 Customer.Service.and.Service.Attributes. 19 General.Support. .23 IT.Services.Central.Data.Storage.Services. .27 Research.Computing. .35 Stanford.Email. 39 Network.Services. 43 Telecommunications. .49 Services . 49 Mobility. 53 Information.Security. 57 Communications. 63 Web.Services.and.Collaboration.Tools . 67 Appendix.A:.The.Full.Text.of.Written.Comments. .A-1 Appendix.B:.The.Survey.Instrument. B-. 1 Stanford Information Technology Services 2012 Client Survey • Introduction | a1 Introduction This report provides a summary of the purposes, the methodology and the results of the client satisfac- tion survey sponsored by Stanford Information Technology Services in November, 2012. -

September 2010

September 2010 2 EDITOR'S NOTE Silver and Gold Lafe Low 2 3 VIRTUALIZATIUON Top 10 Virtualization Best Practices Wes Miller 7 SPECIAL REPORT IT Salary Survey Michael Domingo 19 SILVERLIGHT DEVELOPMENT Build Your Business Apps on Silverlight Gill Cleeren and Kevin Dockx 25 TROUBLESHOOTING 201 Ask the right Questions 29 IT MANAGEMENT Stephanie Krieger Managing IT in a Recession – Tips for Survival Romi Mahajan 41 TOOLBOX New Products for IT Professionals 31 SQL Q & A Greg Steen Maintaining Logs and Indexes Paul S. Randal 35 WINDOWS CONFIDENTIAL History – The Long Way Through Raymond Chen 45 UTILITY SPOTLIGHT Create Your Own Online Courses 37 WINDOWS POWERSHELL Lance Whitney Cereal or Serial? Don Jones 48 GEEK OF ALL TRADES Automatically Deploying Microsoft Office 2010 with Free Tools Greg Shields 1 Editor’s Note Silver and Gold Lafe Low TechNet magazine this month looks at developing line of business applications with Silverlight and best practices for managing virtual environments. There are two significant technologies we’ll be covering in TechNet Magazine this month. The first is Silverlight, the Microsoft rich Internet application platform. While Silverlight may have been flying somewhat under the radar in the early days since its introduction several years ago, it’s maturing into a development platform worthy of supporting and running heavy-duty business applications. Probably the most significant change that put Silverlight in the spotlight was the change from JavaScript to .NET as a development model. Check out what Gill Cleeren and Kevin Dockx have to say in ―Build Your Business Apps in Silverlight.‖ The other is virtualization, which has been around long enough and has enough enterprise-grade adoption that companies have developed best practices and tricks and techniques for streamlining and optimizing their infrastructure. -

PRESS CONTACT: Belinda Banks S&S Public Relations (609) 750-9110 [email protected]

PRESS CONTACT: Belinda Banks S&S Public Relations (609) 750-9110 [email protected] AWARD-WINNING GOODSYNC SYNCHRONIZATION UTILITY NOW AVAILABLE FOR MAC OS X Top-Rated Product Enables Users to Backup/Sync Files Between Any Two Devices, Locally or Via Web; New Version Makes File Transfers Between Macs and PCs a Breeze FAIRFAX, VA — (April 7, 2010) — Siber Systems, Inc., a company dedicated to providing world-class computing productivity software for enterprises and individuals, today announced the release of GoodSync for Mac, the first-ever Mac OS X version of its well-known Windows utility for backing up and synchronizing files between computing devices. The application, able to sync as many as five million files at once, brings new convenience and productivity to both Mac and dual Mac/PC environments at home and at work, and is robust enough for even large enterprises. GoodSync for Mac supports Mac OS X 10.4, 10.5 and 10.6, and can be downloaded for personal use at www.goodsync.com/mac. GoodSync for Mac Pro, the professional version featuring unlimited jobs and file synchronization plus free Web and toll-free support, is also available for $29.95. GoodSync is widely regarded as a leading utility for transferring and synchronizing data between any two devices—desktops, laptops, servers, external storage and Windows Mobile devices—in any direction. Winner of numerous awards, GoodSync has been heralded by leading reviewers and publications: “GoodSync has brought unbelievable convenience and peace of mind. The software interface is extremely user-friendly and backed up with an easy-to-use manual.”— Computer Technology Review “We highly recommend this file synchronization tool for all user levels.”—CNET Download.com “GoodSync is one of the nicest-looking and easiest-to-use of the dozen or so sync programs tested.”—PC World “GoodSync V7 is fantastic!”—Geek.com “GoodSync has been popular with Windows users for years—yet many Mac users have been asking for an OS X version. -

The Future of Email Archives

The Future of Email Archives A Report from the Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives August 2018 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES The Future of Email Archives A Report from the Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives August 2018 Sponsored by COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES ISBN 978-1-932326-59-8 CLIR Publication No. 175 Published by: Council on Library and Information Resources 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 Washington, DC 20036 Website at https://www.clir.org Print copies are available for $20 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s website at https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub175/ Copyright © 2018 by Council on Library and Information Resources. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data: Names: Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives, author. | Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, sponsoring body. | Digital Preservation Coalition, sponsoring body. Title: The future of email archives : a report from the Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives, August 2018 / sponsored by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Digital Preservation Coalition. Description: Washington, DC : Council on Library and Information Resources, [2018] | Series: CLIR publication ; no. 175 | “August 2018.” | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018027625 | ISBN 9781932326598 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Electronic mail messages. | Electronic records. | Digital preservation. Classification: LCC CD974.4 .T37 2018 | DDC 004.692--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018027625 Cover illustration: faithie/Shuttertock.com iii Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................vi The Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives .............................. -

Goodsync 101020 Crack

GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack 1 / 4 GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack 2 / 4 3 / 4 25.5 Crack With Activation Code & Free Download 2020 GoodSync 10.10.25.5 Crack is an easy and reliable file backup and file synchronization software. It.... GoodSyncis an easy, safe, and method that is reliable immediately synchronize and back-up your photos.GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack 2020.. GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack an easy, secure, and reliable way to automatically synchronize and backup your photos, MP3s, and important files.. GoodSync 10.10.25.5 Crack registration key is just an improvement that is pivotal that empowers clients to alter reports into the pay list.. Сам процесс довольно умный, GoodSync в автоматическом режиме ... 10.10.20. * Speed and Progress: Added Elapsed Time, better Current Speed .... GoodSync Enterprise Crack is an easy and reliable file backup and file synchronization software It automatically analyzes, synchronizes,.... GoodSync 10.10.20 Keygen is a simple and solid record reinforcement and document synchronization programming. It naturally examines, synchronizes, …. GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack+ Activation Code & Download 2020 GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack is a basic and solid record reinforcement and .... GoodSync Serial Key syncs data Azure, between your notebook FTP Amazon S3 SkyDrive, WebDAV. The principal window has been divided into .... GoodSync 10.10.19.5 Crack is a simple, secure, and dependable approach to naturally synchronize and back up your photographs, MP3s, and relevant .... GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack is a simple and reliable file backup and file synchronization software. GoodSync 10.10.20 Crack With Serial Number Free Download ... -

A Simple and Iterative Reconciliation Algorithm for File Synchronizers

Syncpal: A simple and iterative reconciliation algorithm for file synchronizers Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Marius Alwin Shekow (M.Sc.) aus Tettnang, Deutschland Berichter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. rer. pol. Matthias Jarke Univ.-Prof. Ph. D . Wolfgang Prinz Univ.-Prof. Dr. Tom Gross Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 22. November, 2019 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Universitätsbibliothek verfügbar. Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich, Marius Alwin Shekow, erkläre hiermit, dass diese Dissertation und die darin dargelegten Inhalte die eigenen sind und selbst- ständig, als Ergebnis der eigenen originären Forschung, generiert wurden. Hiermit erkläre ich an Eides statt 1. Diese Arbeit wurde vollständig oder größtenteils in der Phase als Doktoranddieser Fakultät und Universitätangefertigt; 2. Sofern irgendein Bestandteil dieser Dissertation zuvor für einen akademischen Abschluss oder eine andere Qualifikation an dieser oder einer anderen Institution verwendet wurde, wurde diesklar angezeigt; 3. Wenn immer andere eigene- oder Veröffentlichungen Dritter herangezogen wurden, wurden diese klar benannt; 4. Wenn aus anderen eigenen- oder Veröffentlichungen Dritter zitiert wurde, wurde stets die Quelle hierfür angegeben. Diese Dissertation ist vollständig meine eigene Arbeit, mit der Ausnahme solcher Zitate; 5. Alle wesentlichen Quellen von Unterstützung wurden benannt; 6. -

LIS 668, Digital Curation

LIS 668, Digital Curation School of Library and Information Studies University of Wisconsin-Madison Spring 2015 Dorothea Salo (please call me “Dorothea”) [email protected], 608-265-4733 Office address: 4261 Helen C. White Hall Office Hours: by appointment Course link page: http://pinboard.in/u:dsalo/t:668 Course Objectives ! Assess, plan for, manage, and execute a small-scale data-management or digital-preservation project. ! Assess digital or to-be-digitized data for preservability; make yes-or-no accessioning decisions. ! Appropriately manage intellectual-property issues related to data management and digital archiving. ! Understand (and where relevant, apply) technological, economic, and social models of digital preservation and sustainability. ! Understand forms, formats, and lifecycles of digital data across a wide breadth of contexts. ! Evaluate software and hardware tools relevant across the data lifecycle. ! Construct a current-awareness strategy; assimilate substantial amounts of relevant writing. ! Self-sufficiently acquire technical knowledge. This course is designed to assess student progress in the following SLIS program-level outcomes: 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, 3d, 4a, and 4b. Course Policies I wish to fully include persons with disabilities in this course. Please let me know within two weeks if you require accommodation. I will try to maintain the confidentiality of this information. Academic Honesty: I follow the academic standards for cheating and plagiarism set forth by the University of Wisconsin. An explicit goal of this course is self-sufficiency in acquiring knowledge about novel technology. To that end, I will NOT handhold you through every technology we look at. You are expected to exhaust normal information channels before you approach classmates or (especially) me with nuts-and-bolts technology questions. -

Additional Resources

Personal Digital Archiving Train-the-Trainer Workshop Additional Resources July 31, 2014 - Society of Georgia Archivists, Georgia Library Association, ARMA Atlanta Part I: The What and the Why of Personal Digital Archiving Part II: The Landscape of Digital Records Part III: Best Practices for Creating Personal Digital Records Part IV: Ownership and Copyright of Personal Digital Records Part V: Privacy and Security of Personal Digital Records Part VI: Best Practices for Storing Personal Digital Records Part VII: Best Practices for Access and Ongoing Management of Personal Digital Records Part VIII: Best Practices for the Digital Afterlife Digital Preservation Illustrations Part I: The What and the Why of Personal Digital Archiving Digitalpreservationeurope.eu. (2009). “wepreserve” YouTube channel. https://www.youtube.com/user/wepreserve/videos Glenn, H. (2013, July 20). “In The Digital Age, the Family Photo Album Fades Away.” NPR. http://www.npr.org/blogs/alltechconsidered/2013/07/25/205425676/preserving-family-photos-in- digital-age Google Dictionary. (2014). “Record.” http://www.google.com/search?q=define+record Lee, C. (2011). I, Digital: Personal Collections in the Digital Era. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/739914168 Library of Congress. (2014). “Personal Digital Archiving.” http://digitalpreservation.gov/personalarchiving/ Library of Congress Digital Preservation. (2014). “The Signal,” Personal Archiving category. http://blogs.loc.gov/digitalpreservation/category/personal-archiving/ Library of Congress National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program. (2013). Perspectives on Personal Digital Archiving. http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/documents/ebookpdf_march18.pdf Personal Digital Archiving Workshop - July 31, 2014 - Society of Georgia Archivists, Georgia Library Association, Atlanta ARMA - This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.