Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Draft June 2016

BRECONBRECON CONSERVATION CONSERVATION AREAAREA APPRAISAL APPRAISAL Review Brecon Beacons National Park First Draft June 2016 1 BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Review of the Conservation Area Boundary 1 3 Community Involvement 5 4 The Planning Policy Context 5 5 Location and Context 6 6 Historic Development and Archaeology 7 7 Character Assessment 11 7.1 Quality of Place 11 7.2 Landscape Setting 12 7.3 Patterns of Use 13 7.4 Movement 14 7.5 Views and Vistas 15 7.6 Settlement Form 16 7.7 Character Areas 19 7.8 Scale 19 7.9 Landmark Buildings 20 7.10 Local Building Patterns 21 7.11 Materials 24 7.12 Architectural Detailing 25 7.13 Landscape/ streetscape 28 8 Important Local Buildings 33 9 Issues and Opportunities 34 10 Summary of Issues 39 11 Local Guidance and Management Proposals 40 12 Contact Details 42 13 Bibliography 42 14 Glossary of Architectural Terms 43 Appendices 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. The central area and historic suburbs of Brecon comprise one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. The Brecon Conservation Area was designated by the National Park Authority on the 12th June 1970. 1.2 Planning authorities have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Local Development Plan. -

Epynt Plateau and Valleys

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA28 EPYNT PLATEAU AND VALLEYS © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Epynt – disgrifiad cryno Mae Epynt yn nwyrain y Canolbarth, a’i chraidd yw llwyfandir tywodfaen, gwyntog Mynydd Epynt, a groestorrir gan ddyffrynnoedd (lle ceir tir pori) a nentydd cyflym. Defnyddir llawer o’r llwyfandir yn faes hyfforddi milwrol, a chafodd hyn sawl effaith anarferol ar gymeriad y dirwedd. Cyfyngir mynediad y cyhoedd i dir agored, ac y mae amryw dirweddau a thyddynnod amaethyddol yn wag ers eu meddiannu ar gyfer hyfforddiant milwrol yn y 1940au. Ceir planhigfeydd conwydd newydd, hynod ar yr hyn sydd, fel arall, yn llwyfandir o weunydd agored, uchel. Mae rhannau deheuol y llwyfandir yn is, ac o ganlyniad mae tiroedd wedi’u cau yn rhannau uchaf ochrau’r dyffrynnoedd, a cheir rhwydwaith o lonydd culion a gwrychoedd trwchus. Prin yw’r boblogaeth, gydag ychydig aneddiadau yng ngwaelodion y dyffrynnoedd. Mae patrwm o dyddynnod carreg gwasgaredig, llawer ohonynt wedi’u rendro a’u gwyngalchu. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA28 Epynt Plateau and Valleys - Page 1 of 9 Mae llawer o ddefaid yn y bryniau, a llawer o enghreifftiau o wahanu pendant rhwng tir agored y fyddin, nad yw wedi’i wella ac, yn is i lawr, porfeydd amgaeedig, wedi’u gwella, lle mae amaethu’n parhau heddiw. Yn hanesyddol, cysylltwyd y fro â cheffylau, ac y mae’r enw “Epynt” yn tarddu o ddau air Brythonaidd sy’n golygu “llwybrau’r ceffylau”. Summary description Epynt lies in central eastern Wales and is defined by the windswept, sandstone plateau of Mynydd Epynt, which is intersected by pastoral valleys and fast flowing streams. -

Risk Screening Report

Risk Screening Report Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Distances used for this report [m]: 0, 50, 200, 250, 500, 2000, 50000 Dataset Name Data found from search Buffer Zone Distance Powys - Powys UTA Unitary Authority 0 Unitary Authority Source Protection Zones 0611c 0 Predominant Soils Types Drinking Water Protected Areas - River Catchments Drinking Water Protected Areas - Lakes Groundwater Vulnerability Zones Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Groundwater Vulnerability MINOR MINOR_I MINOR_I1 0 Zones 1 National Park Main Rivers Scheduled Ancient Monuments LRC Priority & Protected Species: Coenagrion mercuriale (Southern Damselfly) Local Wildlife Sites Local Nature Reserves National Nature Reserves Protected Habitat: Aquifer fed water bodies Protected Habitat: Blanket bog Protected Habitat: Coastal Saltmarsh Protected Habitat: Coastal and Floodplain Grazing Marsh Protected Habitat: Fens Protected Habitat: Intertidal Mudflats Protected Habitat: Lowland raised bog Protected Habitat: Mudflats Protected Habitat: Reedbeds Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Protected Habitat: Reedbeds Protected Habitat: Wet Woodland LRC Priority & Protected Species: Anisus vorticulus (Little Whirlpool Ramshorn Snail) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Arvicola amphibius (Water vole) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Caecum armoricum (Lagoon Snail) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Cliorismia rustica -

Brycheiniog 39:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 27/4/16 15:59 Page 1

53548_Brycheiniog_39:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 15:59 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG VOLUME XXXIX 2007 Edited by E. G. PARRY Published by THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS 53548_Brycheiniog_39:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 15:59 Page 2 THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA OFFICERS President Sr Bonaventure Kelleher Chairman Mr K. Jones Honorary Secretary Miss H. Guichard Membership Secretary Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Honorary Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Honorary Auditor Mr B. Jones Honorary Editor Mr E. G. Parry Honorary Assistant Editor Mr P. Jenkins Curator of Brecknock Museum and Art Gallery Back numbers of Brycheiniog can be obtained from the Assistant Editor, 9 Camden Crescent, Brecon LD3 7BY Articles and books for review should be sent to the Editor, The Lodge, Tregunter, Llanfilo, Brecon, Powys LD3 0RA © The copyright of material published in Brycheiniog is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 53548_Brycheiniog_39:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 15:59 Page 3 CONTENTS Officers of the Society 2 Notes on the Contributors 4 Editorial 5 Reports: The Royal Regiment of Wales Museum, Brecon Alison Hembrow 7 Powys Archives Office Catherine Richards 13 The Roland Mathias Prize 2007 Sam Adams 19 Prehistoric Funerary and Ritual Monuments in Breconshire Nigel Jones 23 Some Problematic Place-names in Breconshire Brynach Parri 47 Captain John Lloyd and Breconshire, 1796–1818 Ken Jones 61 Sites and Performances in Brecon Theatrical Historiography Sister Bonaventure Kelleher 113 Frances Hoggan – Doctor of Medicine, Pioneer Physician, Patriot and Philanthropist Neil McIntyre 127 The Duke of Clarence’s Visit to Breconshire in 1890 Pamela Redwood 147 53548_Brycheiniog_39:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 15:59 Page 4 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS Sam Adams is a poet and critic who is a member of the Roland Mathias Prize Committee. -

BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Brecon Beacons

BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Brecon Beacons National Park April 2012 1 BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The Planning Context 1 3 Location and Context 2 4 General Character and Plan Form 4 5 Landscape Setting 6 6 Historic Development and Archaeology 9 7 Spatial Analysis 13 8 Character Analysis 20 9 Definition of the Special Interest of the Conservation Area 35 10 The Conservation Area Boundary 35 11 Summary of Issues 36 12 Community Involvement 37 13 Local Guidance and Management Proposals 37 14 Contact Details 40 15 Bibliography 40 16 Glossary of Architectural Terms 41 Appendices, Maps and Drawings 44 (Appendix One, Management Proposals) 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. The central area and historic suburbs of Brecon comprise one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. The Brecon Conservation Area was designated by the National Park Authority on the 12th June 1970. 1.2 Planning authorities also have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Unitary Development Plan. 1.3 The purpose of this appraisal is to define the qualities of the area that make it worthy of conservation area status. -

Core Management Plan Including Conservation Objectives

CYNGOR CEFN GWLAD CYMRU COUNTRYSIDE COUNCIL FOR WALES CORE MANAGEMENT PLAN INCLUDING CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES FOR MYNYDD EPYNT SITE OF SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC INTEREST (SSSI) INCLUDING MYNYDD EPYNT SPECIAL AREA FOR CONSERVATION (SAC) Version: 1 Date: February 2008 Approved by: A Welsh version of all or part of this document can be made available on request. CONTENTS Preface: Purpose of this document 1. Vision for the Site 2. Site Description 2.1 Area and Designations Covered by this Plan 2.2 Outline Description 2.3 Outline of Past and Current Management 2.4 Management Units 3. The Special Features 3.1 Confirmation of Special Features 3.2 Special Features and Management Units 4. Conservation Objectives Background to Conservation Objectives 4.1 Conservation Objective for Feature 1: Varnished hook-moss Hamatocaulis vernicosus (EU Habitat Code: 1393) 4.2 5. Assessment of Conservation Status and Management Requirements: 5.1 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 1: Varnished hook-moss Hamatocaulis vernicosus (EU Habitat Code: 1393) 6. Action Plan: Summary 7. Glossary 8. References 2 PREFACE This document provides the main elements of CCW’s management plan for the sites named. It sets out what needs to be achieved on the sites, the results of monitoring and advice on the action required. This document is made available through CCW’s web site and may be revised in response to changing circumstances or new information. This is a technical document that supplements summary information on the web site. One of the key functions of this document is to provide CCW’s statement of the Conservation Objectives for the relevant Natura 2000 sites. -

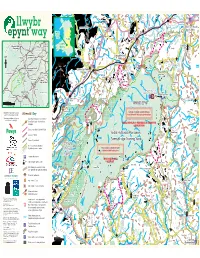

Epynt Way Llwybr

Cilmery llwybr Beulah A483 IRFON FOREST Llanfair-ym-Muallt Builth Wells Llwybr epynt way Epynt Garth Way Powys Irfon Pantyblodau B4356 Trefyclo Cymru Rhaeadr Gwy B4518 Knighton Llanddewi’r A483 B435 Wales Rhayader A44 A488 6 Moelfre Cwm Radnor Forest 9 Cambrian Mountains A4 1 70 B4372 5 Llandrindod B4357 A483 4 B4362 Llanwrtyd Llangammarch B Gog/N Newbridge Llandrindod Wells A44 Pennau on Wye B4358 Wells Maesmynis A470 A483 A481 Gog/N B4358 Brynhynae Llanfair-ym-Muallt The Warren Llangammarch Builth Wells Llanwrtyd Wells Poityn Wells B4520 Llanwrtyd Wells Pentre Dolau B4594 Garn Wen Penrhiw B4519 Honddu Scenic Dingle Errwd B4352 A483 A438 Cefn- Erwood B4350 B4 gorwydd Cw Llwybr A470 348 Upper Llanstephan m Epynt Y Gelli - Chapel Pen m Llethr Ddu Way Hay-on-Wye Derlwyn w Blaen Bwch yn Farm B4520 A483 Mon Talgarth Llandovery A438 A470 Epynt Visitor Centre 069 Aberhonddu Black Mountains Pentre A4 B4560 Canolfan Ymwelwyr Epynt A40 Brecon Dolau Honddu A40 A479 Sennybridge Cw Sugar Loaf Maesyron m A40 Station Ow 10 km A470 MYNYDD EPYNT en Brecon Beacons Tretower Abergefail 10 milltir/miles Cwm Dwfnan 0 Login 52 Sugar Loaf Cadwch at y llwybr awdurdodedig yn B Published by Powys County Council on t 451 B4 behalf of the Epynt Way Partnership. Allwedd / Key Ardal Hyfforddi’r Weinyddiaeth Amddiffyn 9 Cyhoeddwyd gan Gyngor Sir Powys ar Epynt Way (with route section number) / ran Partneriaeth Llwybr Epynt. Tirabad Llwybr Epynt (gyda rhif y rhan honno ARDAL BERYGLUS Y WEINYDDIAETH AMDDIFFYN o’r llwybr) CADWCH DRAW Epynt Circular Route / Cylchdaith -

DTE Wales Public Information Leaflet

Public Access Information There is a presumption in favour of public access to the Defence Training Estate, on Public Rights of Way, balanced against the over-riding national PUBLIC requirement for safe and sustainable military training and conservation. Public DEFENCE TRAINING ESTATE access is not permitted to the camps and training areas at Caerwent. At (Wales) INFORMATION Sennybridge, red flags fly continually along the range boundary and indicating that the area is subject to Military Bylaws. Within this area is situated the newly HQ DTE Wales Major Training Areas created Epynt Way circular permissive bridle path which runs along the Minor Training Areas LEAFLET boundary of the Training Area. The path links in with all the rights of way that Small Arms Ranges come to the edge of the Training Area and allows access to be gained along the circular route. The path is some 60 km long and is extensively waymarked. Public access is actively encouraged along its route, with people on foot, DTE horseback and on bicycles being the likely users.. Co-located with this centre are walks for the disabled and able-bodied, with magnificent views across the WALES & Epynt. When on such a public Right of Way across a training area follow the WEST Country Code: Pwllholm The Country Code • Enjoy the countryside and respect its life and work • Guard against all risk of fire Sennybridge • Use gates and stiles to cross fences, hedges and walls • Leave livestock, crops and machinery alone Caerwent • Take your litter home Rogiet • Take special care on country roads • Make no unnecessary noise • Keep to the public paths across farmland • Fasten all gates • Keep dogs under close control • Protect wild life, plants and trees • Help to keep all water clean ADDITIONAL INFORMATION In addition to this Public Information Leaflet for DTE W, the Defence Training Great care is taken to ensure the safety of these walks, although areas used by Estate and Defence Estates (DE) both produce more literature: the DTE Annual the armed forces for training can obviously be dangerous. -

Access Leaflet

PowAccesysibs le A Guide to Countryside Trails and Sites 1st Edition Accessible Powys A Guide to Countryside Trails and Sites contain more detailed accessibility data and Also Explorer Map numbers and Ordnance We have made every effort to ensure that the Introduction updated information for each site visited as well Survey Grid references and facilities on site information contained in this guide is correct at as additional sites that have been visited since see key below: the time of printing and neither Disabled Welcome to the wealth of countryside within publication. Holiday Information (nor Powys County Council) the ancient counties of Radnorshire, on site unless otherwise stated will be held liable for any loss or Brecknockshire and Montgomeryshire, The guide is split into the 3 historic shires within NB most designated public toilets disappointment suffered as a result of using the county and at the beginning of each section which together make up the present day will require a radar key this guide. county of Powys. is a reference to the relevant Ordnance Survey Explorer maps. at least one seat along route This guide contains details of various sites and trails that are suitable for people needing easier Each site or trail has been given a category accessible picnic table access, such as wheelchair users, parents with which gives an indication of ease of use. small children and people with limited Category 1 – These are easier access routes tactile elements / audio interest walking ability. that are mainly level and that would be suitable We hope you enjoy your time in this beautiful for most visitors (including self propelling For further information on other guides or to and diverse landscape. -

Guided Walks and Events Programme Winter 2011-12

Cymdeithas Parc Bannau Brycheiniog Brecon Beacons Park Society www.breconbeaconsparksociety.org GUIDED WALKS AND EVENTS PROGRAMME WINTER 2011-12 Most of these walks go into the hills. Participants are reminded that the following gear must be taken. Walking boots, rucksack, hats, gloves, warm clothing (not jeans), spare sweater, water and a hot drink, lunch, extra food and of course waterproof jackets and trousers. A whistle and torch should be carried, particularly during the winter months. Participants must satisfy themselves that the walk is suitable for their abilities. You can take advice by ringing the walk leader whose telephone number is given. No liability will be accepted for loss or injury that occurs as a result of taking part. An adult must accompany young people (under 18). MOST OF THESE WALKS ARE FOR EXPERIENCED WALKERS Leaders may change or cancel the advertised route due to adverse weather conditions. Strenuous walks require fitness and stamina to cope with several steep climbs and/or cover a good distance at a steady pace. Energetic walks generally involve two steep climbs but they will still require determined application. Moderate walks will seldom have steep climbs but if they do the climb will be taken at a relaxed pace. Dogs (well controlled) are permitted unless stated otherwise in the programme. It should be noted that under the CROW Act, when taking dogs onto Open Access land they must be on a fixed lead, no more than two metres long, whenever livestock are near, and at ALL TIMES from 1st March to 31st July. Non-members of the Park Society will be asked to make a donation of £5.00 each per walk . -

Sennybridge and Defynnog Assessment Part One Report

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan Sennybridge and Defynnog Assessment Part One Report 8th August 2012 Sennybridge & Defynnog Assessment August 2012 CONTENTS Introduction and Context Section 1 a) Key data relating to the role, function, character and constraints of the Settlement 1. Sennybridge & Defynnog Overview and Key Facts 2. Sennybridge & Defynnog LANDMAP Assessment 3. Sennybridge & Defynnog Sustainability Questionnaire 4. Sennybridge & Defynnog Connectivity 5. Sennybridge & Defynnog Past Planning Policy 6. Sennybridge & Defynnog Flooding 7. Sennybridge & Defynnog Infrastructure and Tourism 8. Sennybridge & Defynnog Community Defined Issues b) The process by which the amendment to the status of Sennybridge and Defynnog was determined by the Authority c) The evidence and representations submitted by Maescar Community Council throughout the process Section 2 a) a profile of the character, role and function of the Settlements b) a Vision for the Cluster c) objectives for the Cluster d) areas vulnerable to the impact of future development Appendices Appendix I – Sennybridge & Defynnog LANDMAP Assessment Findings Appendix II – Deposit Representations 2 Sennybridge & Defynnog Assessment August 2012 Introduction and Context Part One Reports Part One reports provide an overview of the settlement in context, drawing on a diverse range of evidence to consider constraints and opportunities for the future sustainable development of the area. The findings of this review of the evidence base is then summarised into a set of key issues and objectives for the area. Along with this broad structure this report also aims to provide additional information documenting the rationale and associated evidence to respond to the LDP Inspector’s concerns as raised in the Inspector’s Preliminary Note of 2nd February 2012. -

DARK SKY DISCOVERY EXPERIENCES a Starry Night Sky Is One of the Most Spectacular Sights Nature Has to O!Er, Bringing You Closer to the Vastness of the 1

DARK SKY DISCOVERY EXPERIENCES A starry night sky is one of the most spectacular sights nature has to o!er, bringing you closer to the vastness of the 1. Usk Reservoir universe and the wonders of space. Designated a Dark Sky Discovery Site, Usk Reservoir is The skies above our park are some of the darkest in the world o"cially recognised as an excellent place to stargaze. Just – with truly world-class stargazing opportunities, remarkable a few miles from the source of the river Usk, this remote backdrops, fascinating landmarks and points of interest. reservoir is set among the forest and moorland of the Usk We’re proud to have achieved the prestigious International Valley, overlooking the Black Mountain. Dark Sky Reserve status, which makes us a renowned The car park area at Usk Reservoir is a beautiful place destination for dark sky discovery. to have a picnic as well as an ideal place to take in Whether you’re finding nebulae with friends, picking outstanding dark skies. The large flat area allows you to out planets with the kids or contemplating the skies on a set up telescopes and the road access from Trecastle stargazing date, our fantastic range of dark sky discovery means it’s easy to get to. experiences will suit beginners and experts alike. Most of the summits in the Black Mountain range are So many adventures await you on a clear night in the park. visible from the reservoir – see if you can pick out Fan Look up and you’ll see the Milky Way, the constellations, Hir, Fan Brycheiniog, Fan Foel, Picws Du and Waun bright nebulae, clusters and more… Why not make your next Lefrith before nightfall.