The Forgotten Citadel of Stok Mon Mkhar1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stok Kangri Expedition Towering at an Impressive 6153 M, Stok Kangri Is a Serious Challenge

Stok Kangri Expedition Towering at an impressive 6153 m, Stok Kangri is a serious challenge. Although at such an impressive height, it is not a technical climb and in season requires no advanced mountaineering equipment. We work our way up to base camp over a number of days to maximize acclimatization and improve chances of a successful summit attempt. The view from the top is one of the best in the Himalaya offering great views of the Zanskar and Karakoram ranges including K2 (8611 m), the second highest peak in the world. This is one of the most popular trekking peaks in the Indian Himalayas and it's proximity to Leh makes it very accessible. Recommend for those wishes to climb a non-technical 6000 m peak. DAY 01: Delhi - Leh (3500 m): 1 hr. flight Take the short flight to Leh, the capital of Ladakh. This is an incredible flight over the greater Himalayas with spectacular views of K2 among others, to one of the world's highest airports. We spend the day in Leh to acclimatize. Take the time to explore the monasteries and markets, or just relax at the hotel. Overnight hotel. DAY 02: Leh We spend the day in Leh for further acclimatization. We go on a short-day hike to practice exercising at this elevation. Marvel at Stok Kangri which is perched on the other side of the valley and begin to measure the size of the challenge ahead. Overnight hotel. DAY 03: Leh - Zingchan (3900 m): 5/6hrs We take a one-hour drive to Spitok, the closest road access to Stok Kangri. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum. -

Mulgrave Ladakh 2017 Dec 29

Mulgrave School Challenge, discovery & service in Ladakh June 28 > July 16, 2017 Mulgrave School - Adventure in Ladakh 2017 Arrival and Indus Valley Exploration ➢ June 28 Fly from Vancouver 11.30 am> Arrive Toronto 7.00 pm > Depart for Delhi 10.55pm ➢ June 29 Delhi Overnight. Arrive Delhi 10.25pm. Collect Medical Cargo. Wait for early morning flight to Leh ➢ June 30 Depart Delhi 5.40 am – Arrive Leh 7.05 amTransport to Stok Highland. Lunch, dinner / R & R at Stok Highland Hotel ➢ July 02 Leh / Lamdon in morning. Lunch at School. Afternoon exploration of Shey & Thiksey with Lama Palden ➢ July 03 Meditation classes & Medical Service Projects ➢ July 04 Meditation & Medical Service Projects ➢ July 05 Stok village hike. Tent set-up and assignments. Final trek preparations Indus > Matho Valley Trek ➢ July 06 Begin Matho Valley trek. Camp above Stok village ➢ July 07 Trek to Stok Kang Ri La Basecamp ➢ July 08 Full day in Stok Kang Ri La Basecamp ➢ July 09 Trek over Matho La. Camp in lower meadow ➢ July 10 Explore Matho Valley ➢ July 11 Trek to Shang Ri la pass ➢ July 12 Cross pass. Camp near Shang monastery ➢ July 13 Trek to Shang Sumdo. Finish trek > transfer back to Stok Free day and return to Vancouver ➢ July 14 Free day ➢ July 15 Fly Leh 8.20 am to Delhi. Day in Delhi. Depart Midnight to Toronto ➢ July 16 Arrive Toronto 5.00am Depart for Vancouver 06.30 am Arrive Vancouver 08.35 am Video Footage • The Song Collector Erik Koto • https://Clps from Leh and Ladakh • https://Clips from Leh and Ladakh Where is Ladakh? Ladakh Singapore > New Delhi ➢ Ladakh is an extremely remote region of India situated on the north side of the great Himalayan mountain range on the vast Tibetan Plateau. -

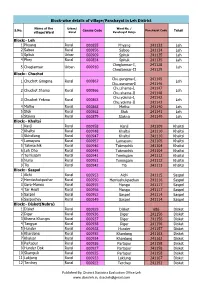

Village Code

Block-wise details of village/Panchayat in Leh District Name of the Urban/ Ward No. / S.No. Census Code Panchayat Code Tehsil village/Ward Rural Panchayat Halqa Block:- Leh 1 Phyang Rural 000855 Phyang 241133 Leh 2 Saboo Rural 000856 Saboo 241134 Leh 3 Spituk Urban 000909 Spituk 241135 Leh 4 Phey Rural 000854 Spituk 241135 Leh Choglamsar-I, 241128 5 Choglamsar Urban 000910 Leh Choglamsar-II 241129 Block:- Chuchot Chu.gongma-I, 241145 1 Chuchot Gongma Rural 000867 Leh Chu.gongma-II 241146 Chu.shama-I, 241147 2 Chuchot Shama Rural 000866 Leh Chu.shama-II 241148 Chu.yokma-I, 241142 3 Chuchot Yokma Rural 000863 Leh Chu.yokma-II 241143 4 Matho Rural 000868 Matho 241140 Leh 5 Stok Rural 000862 Stok 241141 Leh 6 Stakna Rural 000879 Stakna 241149 Leh Block:- Khaltsi 1 Kanji Rural 000958 Kanji 241109 Khaltsi 2 Khaltsi Rural 000948 Khaltsi 241110 Khaltsi 3 Skindiang Rural 000947 Khaltsi 241110 Khaltsi 4 Lamayuru Rural 000957 Lamayuru 241105 Khaltsi 5 Takmachik Rural 000946 Takmachik 241104 Khaltsi 6 Leh Dho Rural 000945 Takmachik 241104 Khaltsi 7 Temisgam Rural 000941 Temisgam 241112 Khaltsi 8 Nurla Rural 000951 Temisgam 241112 Khaltsi 9 Tia Rural 000942 Tia 241113 Khaltsi Block:- Saspol 1 Alchi Rural 000953 Alchi 241115 Saspol 2 Hemisshukpachan Rural 000950 Hemisshukpachan 241116 Saspol 3 Gera-Mangu Rural 000955 Mangu 241117 Saspol 4 Tar Hepti Rural 000956 Mangu 241117 Saspol 5 Saspol Rural 000952 Saspol 241114 Saspol 6 Saspochey Rural 000949 Saspol 241114 Saspol Block:- Disket(Nubra) 1 Disket Rural 000929 Disket 686 Disket 2 Diger Rural 000936 -

Project Impacts Stakeholders’ Testimonials Project Impacts Stakeholders’ Testimonials

NOVEMBER 2012 PROJECT Stakeholders’ testimonials IMPACTS PROJECT IMPACTS Stakeholders’ testimonials Remote in the west Himalayan range, the valleys of To take optimum benefit of solar radiation and retain these desert areas lye at more than 3,000masl. They heat, the consortium of NGOs has developed low-en- are characterized by temperatures that can easily ergy consumption houses and buildings. Families can drop below –20°C during harsh and long winter, a build such passive solar rooms with local materials short frost-free period, meagre annual rainfall (10- and techniques, at affordable cost, saving up to 60% 100mm) and scarce vegetation. Villages are isolated in fuel and reducing pressure on the environment. both geographically and economically. Shortage of lo- cal fuel and high price of imported fossil fuels result in Awareness and adaptation to climate change energy vulnerability. Since thermal efficiency of most Over the last few years, impacts of climate change of the buildings is poor, indoor temperature often falls have been increasingly visible in Ladakh and Lahaul below -10°C in winter. Living conditions are all the & Spiti. Rainfall and snowfall patterns have been more difficult as combustion in traditional stoves pro- changing; small glaciers and permanent snow fields duce lots of unhealthy smoke. Besides, the impacts of are melting affecting water runoff in the rivers and global climate change have been increasingly percep- streams, and rise in temperature and humidity induc- tible in the region over the last 10 years. ing favourable conditions for the invasion of insects and pest aggression. The consortium’s approach was This region benefits from an exceptional sunshine of to assess the impacts specific to the project region, around 300 days per year, exploitable for the dissem- as it had never been done in the past. -

LEH (LADAKH) (NOTIONAL) I N E Population

JAMMU & KASHMIR DISTRICT LEH (LADAKH) (NOTIONAL) I N E Population..................................133487 T No. of Sub-Districts................... 3 H B A No of Statutory Towns.............. 1 No of Census Towns................. 2 I No of Villages............................ 112 C T NUBRA R D NUBRA C I S T T KHALSI R R H I N 800047D I A I LEH (LADAKH) KHALSI I C J Ñ !! P T ! Leh Ladakh (MC) Spituk (CT) Chemrey B ! K ! I Chuglamsar (CT) A NH 1A I R Rambirpur (Drass) nd us R iv E er G LEH (LADAKH) N I L T H I M A A C H A L P R BOUNDARY, INTERNATIONAL.................................. A D E S ,, STATE................................................... H ,, DISTRICT.............................................. ,, TAHSIL.................................................. HEADQUARTERS, DISTRICT, TAHSIL....................... RP VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION Ladda WITH NAME................................................................. ! DEGREE COLLEGE.................................................... J ! URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE:- III, IV, VI. ! ! HOSPITAL................................................................... Ñ NATIONAL HIGHWAY................................................. NH 1A Note:- District Headquarters of Leh (Ladakh) is also tahsil headquarters of Leh (Ladakh) tahsil. RIVER AND STREAM................................................. JAMMU & KASHMIR TAHSIL LEH DISTRICT LEH (LADAKH) (NOTIONAL) Population..................................93961 I No of Statutory Towns.............. 1 N No of Census Towns................ -

Leh(Ladakh) District Primary

Census of India 2011 JAMMU & KASHMIR PART XII-B SERIES-02 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK LEH (LADAKH) VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS JAMMU & KASHMIR CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 JAMMU & KASHMIR SERIES-02 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK LEH (LADAKH) VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations JAMMU & KASHMIR MOTIF Pangong Lake Situated at a height of about 13,900 ft, the name Pangong is a derivative of the Tibetan word Banggong Co meaning "long, narrow, enchanted lake". One third of the lake is in India while the remaining two thirds lies in Tibet, which is controlled by China. Majority of the streams which fill the lake are located on the Tibetan side. Pangong Tso is about five hours drive from Leh in Ladakh region of Jammu & Kashmir. The route passes through beautiful Ladakh countryside, over Chang La, the third highest motorable mountain pass (5289 m) in the world. The first glimpse of the serene, bright blue waters and rocky lakeshore remains etched in the memory of tourists. There is a narrow ramp- like formation of land running into the lake which is also a favorite with tourists. During winter the lake freezes completely, despite being saline water. The salt water lake does not support vegetation or aquatic life except for some small crustaceans. However, there are lots of water birds. The lake acts as an important breeding ground for a large variety of migratory birds like Brahmani Ducks, are black necked cranes and Seagulls. One can also spot Ladakhi Marmots, the rodent-like creatures which can grow up to the size of a small dog. -

Th360⁰rendezvous with Life

Th360⁰ Rendezvous with life ITINERARY – BEST OF LADAKH PACKAGE (8 nights / 9 days) Day 1: Leh An early morning arrival at Leh airport, you will be greeted by your guide and transferred directly to your hotel. After check-in, spend the day taking rest and adapting to the high altitude of Ladakh. In the late afternoon visit the beautiful Shanti stupa and capture some magnificent photos at sunset. Overnight stay inLeh hotel. Day 2: Leh - Shey - Stok - Thiksey–Hemis - Leh Start your morning with a picturesque drive to Shey Village and a visit to Shey Monastery and Palace (both built in 1655 as summer retreat spaces for the reigning King). Proceed toStok Palace museum to learn about the royal kingdoms of Ladakh and have a chance to view many royal artefacts and paraphernalia dating back to the 11th century. Have lunch in the lama run restaurant in beautiful Thiksey monastery, then take an overland safari drive to Hemisgompabefore returning to Leh for your overnight stay. Day 3: Pangong Lake This morning you will take another scenic drive to the magnificent Pangong Lake - a must see destination for your time in Ladakh and made famous by the 'Three Idiots' movie. More than half of Pangong Lake separatesLadakh from China, and the appearance of the water changes colour at every angle of the sun. This experience makes for some amazing photographs so don’t forget your camera! Return to Leh in the afternoon in time for souvenir shopping in the local bazar. Overnight stay in Leh hotel. Day 4: Nubra Valley – Disket – Hundar An early morning departure for ‘Nubra Valley’ - popularly known as the ‘valley of flowers’. -

The Korchen & Siklis Combination Trek

COMMUNITY ACTION TREKS LTD Stewart Hill Cottage, near Hesket Newmarket, Wigton, Cumbria CA7 8HX Tel: 017684 84842 Email: [email protected] Web: www.catreks.com LADAKH - MARKHA VALLEY AND THREE PASSES Grade: Demanding Land-only duration: 18 days Delhi - Delhi Trekking days: 10 Maximum altitude: 5274m Minimum numbers: Requires just 4 participants to guarantee these departures at the advertised price. Dates and prices: Our latest dates and prices list is available at www.catreks.com or from the CAT office. Registered in England No. 4402182 Directors: Doug Scott CBE, Martin West and Jeff Frew The secluded Markha Valley is wedged between the Ladakh and Zanskar ranges, behind the Himalaya, to which it runs parallel. The wild and barren, yet hauntingly beautiful landscapes of this hidden land are often likened to Tibet – Ladakh used to be known as „Little Tibet‟ - and are every bit as dramatic and enticing. Our trip starts in the fascinating capital of Leh, which developed as a trading centre, drawing merchants from Yarkand, Kashmir, Tibet and North India. During our 3 day stay, which is essential for proper acclimatisation, we explore its colourful bazaars and backstreets, dominated by the splendid Leh Palace, which is like a miniature version of Lhasa‟s Potala. We also visit several of the outlying historical and cultural gems of Ladakh, including the 500 year old Shey palace and gompa, Tikse and Hemis monasteries and the royal palace at Stok, all of which provide an insight into the rich heritage of the region. The circular trek itself starts from Stok, climbing steadily to cross the first of the passes, the 4848m Stok La. -

Shortening and Erosion Across the Indus Valley, NW Himalaya

Squeezing river catchments Squeezing river catchments through tectonics: Shortening and erosion across the Indus Valley, NW Himalaya H.D. Sinclair1,†, S.M. Mudd1, E. Dingle1, D.E.J. Hobley2, R. Robinson3, and R. Walcott1,4 1School of GeoSciences, The University of Edinburgh, Drummond Street, Edinburgh, EH8 9XP, UK 2Department of Geological Sciences/Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado, UCB 399, 2200 Colorado Avenue, Boulder, Colorado 80309-0399, USA 3Department of Earth Sciences & Environmental Sciences, University of St. Andrews, Irvine Building, St. Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK 4Department of Natural Sciences, National Museums Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1JF, UK ABSTRACT lake development. Conglomerates beneath and Molnar, 2001). Similarly, the river catch- some of the modern alluvial fans indicate ments of the Southern Alps of New Zealand are Tectonic displacement of drainage divides a northeastward shift of the Indus River understood to have been deformed to their pres- and the consequent deformation of river channel since ca. 45 ka to its present course ent shape during oblique convergence (Koons, networks during crustal shortening have against the oppo site side of the valley from 1995; Castelltort et al., 2012). Tectonically been proposed for a number of mountain the Stok thrust. The integration of structural, induced changes in catchment shape may be fur- ranges, but never tested. In order to pre- topographic, erosional, and sedimentological ther modified by river capture and progressive serve crustal strain in surface topography, data provides the first demonstration of the migration of drainage divides in response to fac- surface displacements across thrust faults tectonic convergence of drainage divides in tors such as variability in rock strength (Bishop, must be retained without being recovered by a mountain range and yields a model of the 1995), changing river base levels (Mudd and consequent erosion. -

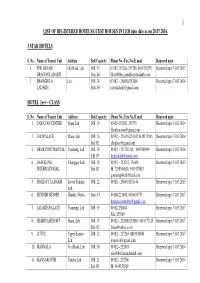

1 LIST of REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES in LEH Upto Date As on 20.07.2016

1 LIST OF REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES IN LEH upto date as on 20.07.2016. 3 STAR HOTELS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. THE GRAND Old Road, Leh D R. 53 01982-255266, 257786, 9419178239 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 DRAGON LADAKH Suits 06 Hotel@the granddragonladakh.com 2. SHANGRILA Leh D R. 24 01982 – 256050/253869 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 LADAKH Suits 03 [email protected] HOTEL (A+) – CLASS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. CARAVAN CENTRE Skara Leh D R. 29 01982-252282, 253779 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 [email protected] 2. CHO PALACE Skara, Leh. D R. 26 01982 – 251659/251142,9419179565 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 Suit 02 [email protected] 3. DRUK CONTINENTAL Yourtung, Leh D R. 38 01982 – 251702, M: - 9697000999 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 S R. 03 [email protected] 4. GAWALING Changspa, Leh. D R. 18 01982 – 253252, 256456 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 INTERNATIONAL Suit 02 M. 7298540620, 9419178813 [email protected] 5. HOLIDAY LADAKH Lower Tukcha, D R. 22 01982 – 250403/251444 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 Leh. 6. HUNDER RESORT Hunder, Nubra Suits 15 01980-221048, 9469453757 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 [email protected] 7. LADAKH PALACE Yourtung, Leh D R. 19 01982-258044 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Fax. 255989 8. LHARISA RESORT Skara, Leh. D R. 15 01982 – 252000/252001, 9419177425 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Suit 02 [email protected] 9. -

Employee List of Leh and Sub Division Likir, Kharu, Nyoma

EMPLOYEE LIST OF LEH AND SUB DIVISION LIKIR, KHARU, NYOMA & DURBUK EMP Name Father Name Sex Mobile Permanent DESIGNATION POSTINGPLACE Payscale Home Posting EPICNO DEP Department CODETAILS S. No. CODE Address Ac Ac AS 0700727 SHANAZ G HAIDER Female 9469512810 SHENAM 194101 SMS LEH Level-6E (35900- LEH LEH BBF0180679 P0 COMMAND AREA DEPUTY DIRECTOR 1 TABASSUM 113500) DEVELOPMENT 0700017 TASHI SONAM TSERING Female 9906970844 SELDOR, CHUCHOT SOP DSEO LEH Level-7 (44900- LEH LEH BBF0556001 P0 ECONOMICS AND DISTT STAT AND 2 DOLMA YOKMA 142400) STATISTICS EVALUATION 0702375 TSERING ISHEY TSERING Female 9419299699194101 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-12 (78800- LEH LEH P0 EDUCATIONOFFICER CHIEF EDUCATION 3 YANGDOL 194101 LEH 209200) OFFICER 0702452 YANGCHEM TSERING DORJEYFemale 9419813517 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF0712034 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION 4 DOLMA LEH 166700) OFFICER 0702453 LOBZANG CHHERING Female 9419813517 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF0111419 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION 5 CHOROL DORJEY LEH 166700) OFFICER 0702454 TSERING TSERING Female 8491042775 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF0234229 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION 6 DOLKER STANZIN LEH 166700) OFFICER 0702458 SYANTIA STEPHEN Female 9419288802 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF0503490 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION 7 MUNSHI MUNSHI LEH 166700) OFFICER 0702477 THINLESS TSERING Female 9906097097 LEH LECTURER BOYS SCHOOL Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF0834606 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION 8 ANGMO NURBOO LEH