Lessons from the Dolphins/Richie Incognito Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bullying Prevention Lending Library

BULLYING PREVENTION LENDING LIBRARY Educator Resources Adina's Deck. Award winning DVD series about the fictional detective club, "Adina's Deck" a group of friends who help solve challenges current to today's young people. Grades 4 – 8. Bully-Book. An electronic book with follow-up questions. Grades K – 3. Bully Busters. Arthur M. Horne, Christi L. Bartolomucci and Dawn Newman-Carlson. Teaching manual for helping bullies, victims and bystanders. Grades K – 5. The Bully Free Classroom by Allan L. Beane, PhD. Grades K – 8. Bully Free Lesson Plans by Allen L. Beane, PhD, Linda Beane and Pam Matlock, MA. Grades K – 8. Bully Proof. Developed by Nan Stein, Emily Gaberman and Lisa Sjostrum. A teacher’s guide on teasing and bullying for use in grades 4 – 5. Bully Safe Schools. DVD Bullying Hurts Everyone. DVD. Bullying K – 5: Introductory Videos for Elementary School Students, Teachers, and Parents from the authors of Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. DVD. Bullying 6 – 8: Introductory Videos for Middle School Students, Teachers, and Parents from the authors of Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. DVD. Bullying: Prevention and Intervention for School Staff. Channing Bete. DVD. Class Meetings That Matter from Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Grades K – 5 & 6 – 8. Cyber Bullying: A Prevention Curriculum by Susan P. Limber, Ph.D., Robin M. Kowalski, Ph.D., and Patricia W. Agatston, Ph.D. Grades 3 – 5 and 6 – 12. Cyberbullying—Safe to Learn: Embedding nti-bullying work in schools from the Pennsylvania Department for Children, Schools and Families. Deanna’s Fund Bullying Prevention Kit. Kit includes a DVD with segments of the theatrical production Doin’ the Right Thing, teacher’s guide and activities. -

Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005)

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2005 Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005) Darby Dickerson John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Education Law Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Darby Dickerson, Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/643 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CYBERBULLIES ON CAMPUS Darby Dickerson * I. INTRODUCTION A new challenge facing educators is how to deal with the high-tech incivility that has crept onto our campuses. Technology has changed the way students approach learning, and has spawned new forms of rudeness. Students play computer games, check e-mail, watch DVDs, and participate in chat rooms during class. They answer ringing cell phones and dare to carry on conversations mid-lesson. Dealing with these types of incivilities is difficult enough, but another, more sinister e-culprit-the cyberbully-has also arrived on law school campuses. Cyberbullies exploit technology to control and intimidate others on campus.' They use web sites, blogs, and IMs2 to malign professors and classmates.3 They craft e-mails that are offensive, boorish, and cruel. They blast professors and administrators for grades given and policies passed; and, more often than not, they mix in hateful attacks on our character, motivations, physical attributes, and intellectual abilities.4 They disrupt classes, cause tension on campus, and interfere with our educational mission. -

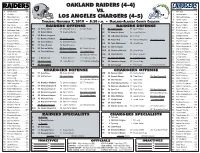

OAKLAND RAIDERS (4-4) NO NAME POS NO NAME POS 4 Derek Carr

OAKLAND RAIDERS (4-4) NO NAME POS NO NAME POS 4 Derek Carr ................ QB 1 Ty Long ........................P VS. 6 AJ Cole ........................P 2 Easton Stick .............. QB 7 Mike Glennon .......... QB LOS ANGELES CHARGERS (4-5) 4 Michael Badgley ..........K 8 Daniel Carlson .............K 5 Tyrod Taylor ............. QB 11 Trevor Davis ............ WR THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2019 – 5:20 P.M. – OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUntY COLISEUM 11 Geremy Davis .......... WR 12 Zay Jones ................. WR RAIDERS OFFENSE RAIDERS DEFENSE 13 Keenan Allen ........... WR 13 Hunter Renfrow ...... WR 16 Andre Patton ........... WR WR 11 Trevor Davis 17 Dwayne Harris 12 Zay Jones DE 96 Clelin Ferrell 97 Josh Mauro 14 DeShone Kizer .......... QB 17 Philip Rivers.............. QB 16 Tyrell Williams ......... WR LT 74 Kolton Miller 75 Brandon Parker DT 73 Maurice Hurst 93 Terrell McClain 20 Desmond King II ....... DB 17 Dwayne Harris ....WR/RS LG 64 Richie Incognito DT 90 Johnathan Hankins 92 P.J. Hall 22 Justin Jackson ............RB 18 Keelan Doss ............. WR C 61 Rodney Hudson 68 Andre James 62 Erik Magnuson 23 Rayshawn Jenkins ....... S DE 99 Arden Key 91 Benson Mayowa 98 Maxx Crosby 20 Daryl Worley .............CB RG 66 Gabe Jackson 71 Denzelle Good 24 Shalom Luani............... S 22 Keisean Nixon............CB SLB 59 Tahir Whitehead 58 Kyle Wilber 25 Melvin Gordon III ......RB RT 77 Trent Brown 72 David Sharpe 25 Erik Harris.................... S MLB 51 Will Compton 26 Casey Hayward Jr. .....CB 26 Nevin Lawson ............CB TE 83 Darren Waller 87 Foster Moreau 85 Derek Carrier 27 Jaylen Watkins ............ S 58 Kyle Wilber 27 Trayvon Mullen .........CB WR 16 Tyrell Williams 13 Hunter Renfrow 18 Keelan Doss WLB 50 Nicholas Morrow 28 Brandon Facyson .......CB 28 Josh Jacobs ................RB 88 Marcell Ateman LCB 20 Daryl Worley 26 Nevin Lawson 30 Austin Ekeler .............RB 29 Lamarcus Joyner ........ -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Week 3 Training Camp Report

[Date] Volume 16, Issue 3 – 8/24/2021 Our goal at Footballguys is to help you win more at Follow our Footballguys Training Camp crew fantasy football. One way we do that is make sure on Twitter: you’re the most informed person in your league. @FBGNews, @theaudible, @football_guys, Our Staffers sort through the mountain of news and @sigmundbloom, @fbgwood, @bobhenry, deliver these weekly reports so you'll know @MattWaldman, @CecilLammey, everything about every team and every player that @JustinHoweFF, @Hindery, @a_rudnicki, matters. We want to help you crush your fantasy @draftdaddy, @AdamHarstad, draft. And this will do it. @JamesBrimacombe, @RyanHester13, @Andrew_Garda, @Bischoff_Scott, @PhilFBG, We’re your “Guide” in this journey. Buckle up and @xfantasyphoenix, @McNamaraDynasty let’s win this thing. Your Friends at Footballguys “What I saw from A.J. Green at Cardinals practice today looked like the 2015 version,” Riddick tweeted. “He was on fire. Arizona has the potential to have top-five wide receiver group with DHop, AJ, Rondale Moore, and Christian Kirk.” The Cardinals have lots of depth now at QB: Kyler Murray saw his first snaps this preseason, but the wide receiver position with the additions for Green it was evident Kliff Kingsbury sees little value in giving and Moore this offseason. his superstar quarterback an extended preseason look. He played nine snaps against the Chiefs before giving TE: The tight end position remains one of the big way to Colt McCoy and Chris Streveler. Those nine question marks. Maxx Williams sits at the top of the snaps were discouraging, as Murray took two sacks and depth chart, but it is muddied with Darrell Daniels, only completed one pass. -

2016 FOOTBALL ROSTER RATINGS SHEET Updated 8/1/2017

2016 FOOTBALL ROSTER RATINGS SHEET Updated 8/1/2017 AFC East 37 35 39 BUFFALO OFFENSE 37 35 39 POSITION B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R QB Tyrod Taylor 3 3 4 EJ Manuel 2 2 2 Cardale Jones 1 1 1 HB LeSean McCoy 4 4 4 Mike Gillislee OC 3 3 3 Reggie Bush TC OC 2 2 2 Jonathan Williams 2 2 2 WR Robert Woods 3 3 3 Percy Harvin 2 2 2 Dezmin Lewis 1 1 1 Greg Salas 1 2 1 TE Charles Clay 3 3 3 Nick O'Leary OC 2 2 2 Gerald Christian 1 1 1 T Cordy Glenn 3 3 4 Michael Ola 2 2 2 Seantrel Henderson 2 2 2 T Jordan Mills 4 3 4 Cyrus Kouandjio 2 3 2 G Richie Incognito 4 4 4 G John Miller 3 3 3 WR Marquise Goodwin 3 3 3 Justin Hunter 2 2 2 C Eric Wood 4 3 4 Ryan Groy 2 3 2 Garrison Sanborn 2 2 2 Gabe Ikard 1 1 1 Patrick Lewis 1 1 1 WR Sammy Watkins 3 3 3 Walt Powell 2 2 2 Brandon Tate TA TB OA OB 1 1 1 FB/TE Jerome Felton OC 2 2 2 Glenn Gronkowski 1 1 1 AFC East 36 38 34 BUFFALO DEFENSE 36 38 34 POSITION B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R DT Adolphus Washington 2 3 2 Deandre Coleman 1 1 1 DT/DE Kyle Williams 3 4 3 Leger Douzable 3 3 3 Jerel Worthy 2 2 2 LB Lorenzo Alexander 5 5 5 Bryson Albright 1 1 1 MLB Preston Brown 3 3 3 Brandon Spikes 2 2 2 LB Zach Brown 5 5 5 Ramon Humber 2 2 2 Shaq Lawson 2 2 2 LB Jerry Hughes 3 3 3 Lerentee McCray 2 2 2 CB Ronald Darby 3 3 2 Marcus Roberson 2 2 2 CB Stephon Gilmore 3 3 3 Kevon Seymour 2 2 2 FS Corey Graham 3 3 3 Colt Anderson 2 2 2 Robert Blanton 2 2 2 SS Aaron Williams 3 3 2 Sergio Brown 2 2 2 Jonathan Meeks 2 2 2 NT Marcell Dareus 3 3 3 Corbin Bryant 2 3 2 DB James Ihedigbo 3 3 2 Nickell Robey-Coleman 2 3 -

In the Shadow of the Law: the Silence of Workplace Abuse

IN THE SHADOW OF THE LAW: THE SILENCE OF WORKPLACE ABUSE PhD Candidate: Ms Allison Jean Ballard Supervisors: Professor Patricia Easteal, AM Assistant Professor Bruce Baer Arnold Month and Year of Submission: January 2019 Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law (941AA) The University of Canberra, Bruce, Australian Capital Territory, Australia Acknowledgements Somewhat uncommonly perhaps, I have been fortunate to have had the same two supervisors throughout my PhD journey. It has been a privilege and a huge pleasure to be guided by, and to learn from my primary supervisor (now Emeritus) Professor Patricia Easteal AM and my secondary supervisor, Assistant Professor Bruce Baer Arnold. Patricia in particular has been my rock. Without Patricia’s amazing kindness, guidance, encouragement, and friendship, I would have ‘thrown in the towel’ and left the PhD boxing ring long ago. Without her support, my well-developed ability to procrastinate (God, help me to finish everything I sta….)1 and to be distracted (God, help me to keep my mind on th– … Look a bird – ing at a time)2 would have reigned supreme. So, my immeasurable thanks to the extraordinary Patricia. Bruce, ever pragmatic and focused on the end game, reminded me to stay focused, helping me to tow the academic line, not take off on too many ‘flights of fancy’, and to check my footnotes! It has been a rollercoaster journey that has spanned three different careers across six different sectors. During this time, I have also started a pro bono virtual legal practice, and established, with my dear friend, and fellow academic, traveller, and shoe-shopper, Doris Bozin, one of the first university-based health-justice legal advice clinics. -

PREVENTING and ERADICATING BULLYING “Creating a Psychologically Healthy Workplace”

PREVENTING and ERADICATING BULLYING “Creating a Psychologically Healthy Workplace” RESOURCE GUIDE And TALKING POINTS for LEADERS AND CHANGE CHAMPIONS March 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 Section I: Resource Guide 4-18 Working Definition and Example Language Describing Bullying 5 Factors to Consider When Evaluating The Example Language 6 Other Definitions of Bullying 7 Types of Bullying 7 Examples of Bullying Behavior and Its Impact 8 Research Results Related to Bullying: Elementary and Secondary Education 9 Research Related to Bullying: College and Universities 10 Research Related to Bullying: The American Workplace 12 Leading and Best Practices to Prevent and Address Bullying 13 What Not To Do: Misdirection In Bullying Prevention and Response 14 The Namie Blueprint to Prevent and Correct Workplace Bullying 15 History of Workplace Bullying 17 SECTION II: TALKING POINTS 19-35 Presentation Slides 20 Conversations About Bullying: An Activity 31 SECTION III: RESOURCES 36-39 1 INTRODUCTION Awareness of bullying as an undesirable and harmful behavior has increased over the past few years. From grade schools to colleges, from workplaces to professional sports, stories about bullying and its debilitating and sometimes life-threatening impact have become part of everyday communications. Leading print and digital newspapers have dedicated feature articles on the subject. The Internet, through social media sites and blogs, has posted numerous comments about school and workplace bullying. In July of 2010, Parade magazine, a syndicated periodical distributed with Sunday editions of newspapers across the country, asked its readers if “workplace bullying should be illegal?” More than 90 percent of the respondents said yes. As recent as February 2014, USA Today, a major national publication, published an article entitled, “Hurt Can Go On Even After Bullying Stops.” The article indicated that early intervention is key to stop bullying because the health effects can persist even after bullying stops. -

Le Mobbing En Milieu Académique Mieux Comprendre Le Phénomène Pour Mieux L’Enrayer

OCTOBRE 2018 Rapport de recherche Le mobbing en milieu académique Mieux comprendre le phénomène pour mieux l’enrayer Crédits Recherche et rédaction Véronique Tremblay-Chaput Chercheuse Révision et mise en page Jean-Marie Lafortune Président, FQPPU Maryse Tétreault Professionnelle de recherche, FQPPU Hans Poirier Professionnel de recherche, FQPPU Fédération québécoise des professeures et professeurs d’université 666, rue Sherbrooke Ouest #300 Montréal (Québec) H3A 1E7 1 888 843 5953 / 514 843 5953 www.fqppu.org Dépôt légal : 3e trimestre 2018 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec ISBN : 978-2-921002-32-5 (br.) ISBN : 978-2-921002-33-2 (PDF) Le mobbing en milieu académique : mieux comprendre le phénomène pour mieux l’enrayer - FQPPU _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Avant-propos Le mobbing au travail est un sujet dont on entend de plus en plus parler dans les couloirs des universités. Il ne fait pas de doute que ce phénomène réfère à une forme particulière de harcèlement, que l’on pourrait associer à du harcèlement moral ou psychologique, mais dont la finalité revêt un caractère plus « total » dans la mesure où elle vise l’expulsion de la victime de son milieu de travail. Le mobbing se distingue toutefois d’autres formes de harcèlement en raison de sa dynamique particulière qui engage tant l’organisation que les collègues des victimes. Rumeurs, commentaires désobligeants et atteintes à la réputation sont autant de manifestations du mobbing susceptibles d’affecter gravement le climat de travail dans nos universités, malgré leur caractère insidieux. À la lumière de ces spécificités, ce rapport n’est donc pas une « autre » ressource sur le harcèlement, mais bien un document qui vise à mieux circonscrire le phénomène singulier et peu étudié qu’est le mobbing en milieu académique. -

Support and Mistreatment by Public School Principals As Experienced by Teachers: a Statewide Survey

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Diane Sue Burnside Huffman Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________ Director Dr. Thomas S. Poetter ___________________________________________ Reader Dr. William J. Boone ___________________________________________ Reader Dr. Kathleen Knight Abowitz ___________________________________________ Reader Dr. Andrew M. Saultz ABSTRACT SUPPORT AND MISTREATMENT BY PUBLIC SCHOOL PRINCIPALS AS EXPERIENCED BY TEACHERS: A STATEWIDE SURVEY by Diane Sue Burnside Huffman Skillful teachers are key to developing good schools. Because of this, understanding the school as a workplace is necessary to investigate why teachers leave and what encourages them to stay. The relationship between the principal, as the boss, and the teacher, as the employee, is one under- researched component of the school workplace which is important for developing a broad understanding of teacher turnover. This cross-sectional study uses a definition of principal mistreatment behaviors from the literature in the development of an original mixed method survey and a random sample of teachers from public schools in the State of Ohio to investigate how often principal mistreatment behaviors are experienced by a random sample of teachers in K-12 public schools. Mistreatment behaviors were paired with an opposite principal support behavior using Likert-style response options and were specifically focused on the 2012-2013 school year. Open- ended questions were included which asked for more general experience with principal mistreatment behaviors, effects on the teachers health, opinions about school culture and student bullying, and the effects of principal treatment behaviors on the teachers sense of efficacy and job satisfaction. -

Workplace Bullying and Harassment

Law and Policy Remedies for Workplace Bullying in Higher Education: An Update and Further Developments in the Law and Policy John Dayton, J.D., Ed. D.* A dark and not so well kept secret lurks the halls of higher education institutions. Even among people who should certainly know better than to tolerate such abuse, personnel misconduct in the form of workplace bullying remains a serious but largely neglected problem.1 A problem so serious it can devastate academic programs and the people in them. If allowed to maraud unchecked, workplace bullies can poison the office culture; shut down progress and productivity; drive off the most promising and productive people; and make the workplace increasingly toxic for everyone who remains in the bully dominated environment.2 A toxic workplace can even turn deadly when stress begins to take its all too predictable toll on victims’ mental and physical health, or interpersonal stress leads to acts of violence.3 Higher education institutions are especially vulnerable to some of the most toxic forms of workplace bullying. When workplace bullies are tenured professors they can become like bullying zombies seemingly invulnerable to efforts to stop them while faculty, staff, students, and even university administrators run for cover apparently unable or unwilling to do anything about the loose-cannons that threaten to sink them all. This article examines the problem of workplace bullying in higher education; reviews possible remedies; and makes suggestions for law and policy reforms to more effectively address this very serious but too often tolerated problem in higher education. * This article is dedicated to the memory of Anne Proffitt Dupre, Co-Director of the Education Law Consortium, Professor of Law, Law Clerk for the U.S. -

New England Patriots Vs. Miami Dolphins Sunday, October 27, 2013 • 1:00 P.M

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS VS. MIAMI DOLPHINS Sunday, October 27, 2013 • 1:00 p.m. • Gillette Stadium # NAME ................... POS # NAME .................. POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski ..... K 2 Brandon Fields ........... P 6 Ryan Allen ................... P PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 7 Pat Devlin ................QB WR: 80 Danny Amendola 85 Kenbrell Thompkins 18 Matthew Slater LE: 50 Rob Ninkovich 92 Jake Bequette 99 Michael Buchanan 10 Austin Collie ............. WR 82 Josh Boyce 8 Matt Moore ..............QB 11 Julian Edelman ......... WR LT: 77 Nate Solder 61 Marcus Cannon DT: 72 Joe Vellano 98 Marcus Forston 9 Caleb Sturgis ............. K 12 Tom Brady .................QB LG: 70 Logan Mankins 74 Will Svitek DT: 93 Tommy Kelly 94 Chris Jones 10 Brandon Gibson ....... WR 15 Ryan Mallett ..............QB 11 Mike Wallace ........... WR C: 62 Ryan Wendell 64 Chris Barker RE: 95 Chandler Jones 96 Andre Carter 17 Aaron Dobson ........... WR 17 Ryan Tannehill ..........QB 18 Matthew Slater ......... WR RG: 63 Dan Connolly 74 Will Svitek 64 Chris Barker LB: 52 Dane Fletcher 58 Steve Beauharnais 18 Rishard Matthews .... WR 22 Stevan Ridley ............ RB RT: 76 Sebastian Vollmer 74 Will Svitek LB: 55 Brandon Spikes 52 Dane Fletcher 59 Chris White 20 Reshad Jones ............. S 23 Marquice Cole ............ CB 21 Brent Grimes ............ CB TE: 87 Rob Gronkowski 47 Michael Hoomanawanui 88 Matthew Mulligan LB: 54 Dont'a Hightower 91 Jamie Collins 25 Kyle Arrington ............ CB 22 Jamar Taylor ............ CB 26 Logan Ryan ............... CB WR: 11 Julian Edelman 17 Aaron Dobson 10 Austin Collie LCB: 31 Aqib Talib 23 Marquice Cole 26 Logan Ryan 23 Mike Gillislee ............ RB 27 Tavon Wilson .............DB QB: 12 Tom Brady 15 Ryan Mallett RCB: 37 Alfonzo Dennard 25 Kyle Arrington 24 Dimitri Patterson ......