Wp 411 FINAL.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Struggle of the Linguistic Minorities and the Formation of Pattom Colony

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A CASE STUDY Volume 9 | Issue 1 | June, 2018 | 130-135 e ISSN–2231–6418 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/9.1/130-135 Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in Struggle of the linguistic minorities and the formation of Pattom Colony C.L. Vimal Kumar Department of History, K.N.M. Government Arts and Science College, Kanjiramkulam, Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala) India ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 07.03.2018 Land has many uses but its availability is limited. During the early 1940s extensive Accepted : 28.05.2018 food shortages occurred throughout Travancore. As a result, the government opened forestlands on an emergency basis for food cultivation and in 1941 granted exclusive cultivation rights known as ‘Kuthakapattam’ was given (cultivation on a short-term KEY WORDS : lease) in state forest areas. Soon after independence, India decided to re-organize Kuthakapattam, Annas, Prathidwani, state boundaries on a linguistic basis. The post Independence State reorganization Pattayam, Blocks, Pilot colony period witnessed Tamil-Malayali dispute for control of the High Ranges. The Government of Travancore-Cochin initiated settlement programmes in the High Range HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : areas in order to alter the regional linguistic balance. Pattom colony, which was Vimal Kumar, C.L. (2018). Struggle of sponsored by Pattom Thanupillai ministry, as a part of High Range colonization scheme. the linguistic minorities and the formation It led to forest encroachment, deforestation, soil erosion, migration, conflict over control of Pattom Colony. Adv. Res. J. Soc. Sci., of land and labour struggle and identity crisis etc. 9 (1) : 130-135, DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ ARJSS/9.1/130-135. -

Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam (Unaided College) - Shifting of 6 Th and 8 Th Semester Students- 2016-17- Sanctioned- Orders Issued

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA (Abstract) Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam (Unaided College) - shifting of 6 th and 8 th semester students- 2016-17- sanctioned- orders issued. ACADEMIC ‘BI’ SECTION No. AcBI/12235/2017 Thiruvananthapuram, Dated: 17.03.2017 Read: 1.UO No.Ac.BI/13387/2002-03 dated 23.05.2003 2.Letter No. ASC(P)19/17/HO/TVPM/ENGG/TEC dated 15.02.2017 from the Admission Supervisory Committee for Professional Colleges. 3.Additional item No.2 of the minutes of the meeting of the Syndicate held on 10.02.2017. 4.Minutes of the meeting of the Standing Committee of the Syndicate on Affiliation of Colleges held on 27.02.2017 ORDER The University of Kerala vide paper read (1) above granted provisional affiliation to the Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam to function on self financing basis from the academic year 2002-03. Various complaints had been received from the students of Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam, their parents and teachers regarding the non conduct of classes and non payment of salary to teachers. In view of the above grave issues in the college, the Admission Supervisory Committee vide paper read as (2) above requested the University to take necessary steps to transfer the students of S6 and S8 to some other college/ colleges of Engineering. The Syndicate held on 10.02.2017 considered the representation submitted by the Students of Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor and resolved to entrust the Convenor, Standing Committee of the Syndicate on Examinations and Students Discipline and the Controller of Examinations to reallocate the students to neighboring college for the conduct of lab examinations for the 5 th Semester students and to work out the modalities for their registration to the 6 th Semester. -

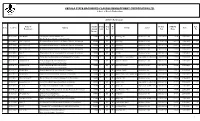

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Epochal Milestone for Ismaili Muslims – History in Making His Highness

Epochal milestone for Ismaili Muslims – History in making His Highness the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee on 11 July 2018 – Lisbon On 11 July 2018, some 66,000 Ismaili Muslims came to Lisbon to pay Homage to their Imam6, His Highness the Aga Khan. They all participated and prayed in a religious congregation for blessings, prayers, & His guidance. This is called a Deedar1. This day marked the end of the Diamond jubilee, which was also celebrated with events exhibitions, music & dancing. This is called the Darbar2 H.H. The Aga Khan asked all his community to “work together, build together, come together within the countries, across frontiers, create capacity, protect yourselves from risks. So that future generations of the Jamat are ensured of a quality of life, which you and I would wish for them” This, was a very special and momentous day in the life and history of all Ismailis who came, and for every one of the more than 15 million Ismailis, worldwide The following makes this a historic milestone, into an epochal day for Ismaili Muslims; • Mawlana Hazar Imam6 gave Deedar1 to the congregation of about 66,000, with His Firmans5 • The global Seat-Dewan4 of the Ismaili Imamat was formally ordained • H.H. The Aga Khan made a speech in Parliament12 • President of Portugal joined the religious congregation (Deedar1) with Mawlana Hazar Imam. Within the Limit of the Holy ground, he removed his shoes out of respect, and made a touching speech. Dewan of the Ismaili Imamat – End of the Diamond Jubilee 11 July 2018 1 of 44 • H.H. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Annual Report 2016-17 Maharaja Martand Singh Judeo White Tiger

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 MAHARAJA MARTAND SINGH JUDEO WHITE TIGER SAFARI & ZOO ABOUT ZOO: The Maharaja Martand Singh Judeo white tiger safari and zoo is located in the Mukundpur of Satna district of Rewa division. The zoo is 15 km far from Rewa and 55 km far from Satna. Rewa is a city in the north-eastern part of Madhya Pradesh state in India. It is the administrat ive centre of Rewa District and Rewa Division In nearby Sidhi district, a part of the erstwhile princely state of Rewa, and now a part of Rewa division, the world's first white tiger, “Mohan” a mutant variant of the Bengal tiger, was reported and captured. To bring the glory back and to create awareness for conservation, a white tiger safari and zoo is established in the region. Geographically it is one of the unique region where White Tiger was originally found. The overall habitat includes tall trees, shrubs, grasses and bushes with mosaic of various habitat types including woodland and grassland is an ideal site and zoo is developed amidst natural forest. It spreads in area of 100 hectare of undulating topography. The natural stream flows from middle of the zoo and the perennial river Beehad flows parallel to the northern boundary of the zoo. The natural forest with natural streams, rivers and water bodies not only makes the zoo aesthetically magnificent but also provides natural environment to the zoo inmates. The zoo was established in June 2015 and opened for the public in April 2016. VISION: The Zoo at Mukundpur will provide rewarding experience to the visitors not about the local wildlife but also of India. -

Geostatistical Modelling of Sediment Chemistry of Ashtamudi Lake Using Gis and Study the Change During Past Several Years

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 GEOSTATISTICAL MODELLING OF SEDIMENT CHEMISTRY OF ASHTAMUDI LAKE USING GIS AND STUDY THE CHANGE DURING PAST SEVERAL YEARS Grace K Mikhayel1, Prof .Chinnamma2 Malabar College of Engineering and Technology, Kerala Technology University, Thrissur (Dist),Kerala,India Abstract Water is valuable natural resources that essential to human survive and the ecosystems health. Water are comprises of coastal water bodies and fresh water bodies (lakes, river and groundwater). Since the past few decades, the increasing of anthropogenic activities especially in industrial area has effects to water bodies. This is the global issues which happening throughout the world and Kerala also face these problems. This study attempts to show the spatial distribution of sediment chemical parameters in the Ashtamudi Lake, Kollam and study the change during several past years. It also shows the partitioning of heavy metals in lake water. The Ashtamudi Lake is the second largest wetland ecosystem in Kerala. The lake is polluted by nearby factories, oil mills, boats, septic wastes etc. Sediment play an important role in elemental cycling in the aquatic environment and can be a sensitive indicator for monitoring contaminants in aquatic environment. GIS and remote sensing techniques can be used to make effective maps showing the effective spatial distribution of each parameters. Also sediment samples from various sample locations of Ashtamudi Lake will be collected and testing will be done accordingly. Index Term-Ashtamudi lake1, sediment sample2, sample point3, sample location4,parameters5 1. INTRODUCTION Water is valuable natural resources that essential to human survive and the ecosystems health. Water are comprises of coastal water bodies and fresh water bodies (lakes, river and groundwater). -

![The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8445/the-legend-marthanda-varma-1-c-parthiban-sarathi-1-ii-m-a-history-scott-christian-college-autonomous-nagercoil-488445.webp)

The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 12, December 2017 The legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil. Abstract:-- Marthanda Varma the founder of modern Travancore. He was born in 1705. Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma rule of Travancore in 1929. Marthanda Varma headquarters in Kalkulam. Marthanda Varma very important policy in Blood and Iron policy. Marthanda Varma reorganised the financial department the palace of Padmanabhapuram was improved and several new buildings. There was improvement of communication following the opening of new Roads and canals. Irrigation works like the ponmana and puthen dams. Marthanda Varma rulling period very important war in Battle of Colachel. The As the Dutch military team captain Eustachius De Lannoy and our soldiers surrendered in Travancore king. Marthanda Varma asked Dutch captain Delannoy to work for the Travancore army Delannoy accepted to take service under the maharaja Delannoy trained with European style of military drill and tactics. Commander in chief of the Travancore military, locally called as valia kapitaan. This king period Padmanabhaswamy temple in Ottakkal mandapam built in Marthanda Varma. The king decided to donate his recalm to Sri Padmanabha and thereafter rule as the deity's vice regent the dedication took place on January 3, 1750 and thereafter he was referred to as Padmanabhadasa Thrippadidanam. The legend king Marthanda Varma 7 July 1758 is dead. Keywords:-- Marthanda Varma, Battle of Colachel, Dutch military captain Delannoy INTRODUCTION English and the Dutch and would have completely quelled the rebels but for the timidity and weakness of his uncle the Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma was a ruler of the king who completed him to desist. -

Annexure 1 B - Kollam

Annexure 1 B - Kollam Allotted Mobile Nos Sl.No Designation/Post Allotted Office District Allotted 1 Kollam 9383470770 PAO Kollam District Office Kollam 2 Kollam 9383470102 JDA PDATMA KLM ATMA KLM 3 Kollam 9383470208 AO KB Nedumpana Chathannoor Block 4 Kollam 9383470210 AO KB Kalluvathukkal Chathannoor Block 5 Kollam 9383470213 AO KB Chirakkara Chathannoor Block 6 Kollam 9383470215 AO KB Chathannoor Chathannoor Block 7 Kollam 9383470217 AO KB Adichanelloor Chathannoor Block 8 Kollam 9383470219 AO KB Poothakulam Chathannoor Block 9 Kollam 9383470224 AO KB Paravoor Chathannoor Block 10 Kollam 9383470225 AO KB Sasthamkotta Sasthamcotta Block 11 Kollam 9383470227 AO KB Kunnathur Sasthamcotta Block 12 Kollam 9383470229 AO KB Poruvazhy Sasthamcotta Block 13 Kollam 9383470231 AO KB Sooranadu North Sasthamcotta Block 14 Kollam 9383470233 AO KB Sooranadu South Sasthamcotta Block 15 Kollam 9383470236 AO KB Mynagapally Sasthamcotta Block 16 Kollam 9383470238 AO KB West Kallada Sasthamcotta Block 17 Kollam 9383470316 DD(WM) PAO KLM 18 Kollam 9383470317 DD (NWDPRA) PAO KLM 19 Kollam 9383470318 DD (C ) PAO KLM 20 Kollam 9383470319 DD (YP) PAO KLM 21 Kollam 9383470320 DD (E &T) PAO KLM 22 Kollam 9383470313 DD (H) PAO KLM 23 Kollam 9383470230 TA PAO KLM 24 Kollam 9383470330 APAO PAO KLM 25 Kollam 9383470240 ACO PAO KLM 26 Kollam 9383470347 AA PAO KLM 27 Kollam 9383470550 ADA (Marketing) PAO KLM 28 Kollam 9383470348 ASC DSTL KLM 29 Kollam 9383470338 AO DSTL KLM 30 Kollam 9383470339 ASC MSTL KLM 31 Kollam 9383470331 AO MSTL KLM 32 Kollam 9383470332 ADA -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Echoes of the Past: Revisiting Myths in T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land GAURAB SENGUPTA M.Phil Research Scholar Department of English Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam. Abstract In The Waste Land (1922) T.S.Eliot presents the degraded, infected and corrupted view of modern day London. In the modern day, humanity has lost its faith in religion, in spirituality as well as in other humans. Eliot continuously tries to compare the present situations with the past just to show us that it is not only the present day Europe which is ailing or ill, but people have suffered the same loss even during the past. Since experiences in the modern day world are so complex therefore he compares the present with the past drawing using mythical methods and allusions from Greek and Roman myths, Christian and pre- Christian and pagan myths and rituals to show the decay of humanity in the present day. Eliot in the poem marvelously and skillfully juxtaposes the present with the past. And thus they comment on each other. This paper is an attempt to show how the past still echoes in the present with the images drawn from various civilizations. Keywords: degradation, modern, myth, past, present Introduction: “…the difference between the present and the past is that the conscious present is an awareness of the past in a way and to an extent the past‟s awareness of itself cannot show.” (Tradition and the Individual Talent. -

Ebook Download a Concise History of Modern India 3Rd Edition

A CONCISE HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA 3RD EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Barbara D Metcalf | 9781107672185 | | | | | A Concise History of Modern India 3rd edition PDF Book Possible clean ex-library copy, with their stickers and or stamp s. The third edition of this acclaimed book recounts the key factors - social, economic and political - that have shaped modern-day Australia. A-Z to view, select the "Entries" tab. The original meaning was "bundle of written sheets ", hence "book", especially "book of accounts," and hence "office of accounts," "custom house," "council chamber". Self-governing Southern Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence in as Rhodesia and continued as an unrecognised state until the Lancaster House Agreement. Abbot, The. After recognised independence in , Zimbabwe was a member of the Commonwealth until it withdrew in The divan of the Sublime Porte was the council or Cabinet of the state. They had a fight with the royal family of Ratanpur, defeated the king, and started ruling the Ratanpur estate. Published by Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Download A Concise History Of Australia books , Australia is the last continent to be settled by Europeans, but it also sustains a people and a culture tens of thousands years old. A History of India. Gave up self-rule in , but remained a de jure Dominion until it joined Canada in All pages are intact, and the cover is intact. Until , when a General Legislative Council was formed, each Presidency under its Governor and Council was empowered to enact a code of so-called 'Regulations' for its government. London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 3rd edition, The original meaning was "bundle of written sheets ", hence "book", especially "book of accounts," and hence "office of accounts," "custom house," "council chamber".