The Myth of PREA Zero Tolerance in Texas Prisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Disciple's Prayer Book

A DISCIPLE’S PRAYER BOOK GREEN A DISCIPLE’S PRAYER BOOK Office of Indigenous Ministries 815 Second Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (800) 334-7626 www.episcopalchurch.org/page/indigenous-ministries 2 A DISCIPLE’S PRAYER BOOK GREEN PREFACE Jesus continually says that the disciples are to go preach, teach, and heal. This tool is a guide for disciples, catalysts, catechists, or anyone that is out there, going somewhere, preaching, teaching and healing all those that seek to engage God’s word, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. This resource with a bible is all that is necessary to preach, teach, and heal all who gather to engage the Gospel as disciples of Jesus. It is offered with the intention that local music, customs, language, and other idioms be added and implemented within the simple “liturgies” or services of this book. This Disciple’s Prayer Book is a gift to the Church from Native Episcopalians to be used on our journey together toward becoming a church of disciples in mission to all of God’s creation. Use it in peace with all that God presents you. May the peace of God that passes all understanding be with you all, now and forever. The Rev. John E. Robertson, Missioner Native Ministries-Gospel Based Discipleship 2000 – 2002 3 GREEN A DISCIPLE’S PRAYER BOOK 4 A DISCIPLE’S PRAYER BOOK GREEN CHRIST IS BORN! In the Morning THE GATHERING (The People say the words in bold type.) The People Gather The Gathering Prayer Said in unison Creator, we give you thanks for all you are and all you bring to us for our visit within your creation. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Flashback, Flash Forward: Re-Covering the Body and Id-Endtity in the Hip-Hop Experience

FLASHBACK, FLASH FORWARD: RE-COVERING THE BODY AND ID-ENDTITY IN THE HIP-HOP EXPERIENCE Submitted By Danicia R. Williams As part of a Tutorial in Cultural Studies and Communications May 04,2004 Chatham College Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Tutor: Dr. Prajna Parasher Reader: Ms. Sandy Sterner Reader: Dr. Robert Cooley ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Prajna Paramita Parasher, my tutor for her faith, patience and encouragement. Thank you for your friendship. Ms. Sandy Sterner for keeping me on my toes with her wit and humor, and Dr. Cooley for agreeing to serve on my board. Kathy Perrone for encouraging me always, seeing things in me I can only hope to fulfill and helping me to develop my writing. Dr. Anissa Wardi, you and Prajna have changed my life every time I attend your classes. My parent s for giving me life and being so encouraging and trusting in me even though they weren't sure what I was up to. My Godparents, Jerry and Sharon for assisting in the opportunity for me to come to Chatham. All of the tutorial students that came before me and all that will follow. I would like to give thanks for Hip-Hop and Sean Carter/Jay-Z, especially for The Black Album. With each revolution of the CD my motivation to complete this project was renewed. Whitney Brady, for your excitement and brainstorming sessions with me. Peace to Divine Culture for his electricity and Nabri Savior. Thank you both for always being around to talk about and live in Hip-Hop. Thanks to my friends, roommates and coworkers that were generally supportive. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P. E. 5772 - 15 Caught Up In You .38 Special 5816 - 08 Hold On Loosely .38 Special 5772 - 08 If I'd Been The One .38 Special 5950 - 06 Second Chance .38 Special 4998 - 05 Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation 4998 - 06 While We're Young 1 Girl Nation 5915 - 18 Beautiful 10 Years 5881 - 11 Through The Iris 10 Years 6085 - 15 Wasteland 10 Years 5459 - 07 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 5218 - 08 Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs 1046A -08 These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs 5246 - 14 I'm Not In Love 10cc 6274 - 20 Things We Do For Love, The 10cc 5541 - 04 Cupid 112 5449 - 10 Dance With Me 112 5865 - 18 Peaches And Cream 112 5883 - 04 Right Here For You 112 6037 - 07 U Already Know 112 5790 - 02 Hot And Wet 112 & Ludacris 5689 - 04 Na Na Na 112 & Super Cat 5431 - 05 We Are One 12 Stones 5210 - 20 Chocolate 1975, The 6386 - 01 If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 1975, The 5771 - 18 Love Me 1975, The 6371 - 08 Me And You Together Song (Clean) 1975, The 6070 - 19 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 1975, The 5678 - 02 I'm Different (Clean) 2 Chainz 5673 - 05 No Lie (Clean) 2 Chainz & Drake 5663 - 12 Birthday Song (Clean) 2 Chainz & Kanye West 5064 - 20 Feds Watching (Clean) 2 Chainz & Pharrell 5450 - 20 We Own It 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa 5293 - 09 I Do It (Clean) 2 Chainz Feat. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Cultural Illusions

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2012 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2012 Vol IX No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages OLOGY the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are I judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- LOSOPHY OF I ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AX AND CULTURE ONAL JOURNAL OF PH I INTERNAT ISBN 978-3-631-63867-5 www.peterlang.de PETER LANG CULTURA 2012_263867_VOL_9_No1_GR_A5Br.indd 1 24.07.12 15:37:38 Uhr CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATiONAL JOURNAL OF PHiLOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXiOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2012 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2012 Vol IX No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages OLOGY the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are i judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- LOSOPHY OF i ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contemporary world. CULTURE AND AX AND CULTURE ONAL JOURNAL OF PH i INTERNAT www.peterlang.de PETER LANG CULTURA 2012_263867_VOL_9_No1_GR_A5Br.indd 1 24.07.12 15:37:38 Uhr CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY Cultura. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Unwritten Mp3 Free Download Unwritten PDF Book by Charles Martin (2013) Download Or Read Online

unwritten mp3 free download Unwritten PDF Book by Charles Martin (2013) Download or Read Online. Unwritten PDF book by Charles Martin Read Online or Free Download in ePUB, PDF or MOBI eBooks. Published in 2013 the book become immediate popular and critical acclaim in fiction, christian fiction books. The main characters of Unwritten novel are John, Emma. The book has been awarded with Booker Prize, Edgar Awards and many others. One of the Best Works of Charles Martin. published in multiple languages including English, consists of 368 pages and is available in ebook format for offline reading. Unwritten PDF Details. Author: Charles Martin Book Format: ebook Original Title: Unwritten Number Of Pages: 368 pages First Published in: 2013 Latest Edition: May 7th 2013 Language: English Generes: Fiction, Christian Fiction, Christian, Romance, Contemporary, Novels, Inspirational, Romance, Contemporary Romance, Drama, Adult Fiction, Formats: audible mp3, ePUB(Android), kindle, and audiobook. The book can be easily translated to readable Russian, English, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Malaysian, French, Portuguese, Indonesian, German, Arabic, Japanese and many others. Please note that the characters, names or techniques listed in Unwritten is a work of fiction and is meant for entertainment purposes only, except for biography and other cases. we do not intend to hurt the sentiments of any community, individual, sect or religion. DMCA and Copyright : Dear all, most of the website is community built, users are uploading hundred of books everyday, which makes really hard for us to identify copyrighted material, please contact us if you want any material removed. Unwritten Read Online. Please refresh (CTRL + F5) the page if you are unable to click on View or Download buttons. -

A Bottom Collider Vertex Detector Design, Monte-Carlo Simulation and Analysis Package

a Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory TM-1682 A Bottom Collider Vertex Detector Design, Monte-Carlo Simulation and Analysis Package P. Lebrun Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory P.O. Bat 500 Batavia, Illinois 60510 October 1,199O 4s Operated by Universities Research Association Inc. under contract with the United States Department of Energy A Bottom Collider Vertex detector design, Monte-Carlo simulation and analysis package. P. Lebrun Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, Illin& 60510, USA Abstract : A detailed simulation of the BCD vertex detector is underway. Specifications and global design issuer are briefly reviewed. The BCD design based a” double sided strip detector is described in more detail. The GEANTJ-based Monte-Carlo program and the analysis package used to estLnste detector performance are discussed in detail. The current status of the expected resolution and signal to noise ratio ior the “golden” CP violating mode Bd + T+Z- is prcsmtcd. These calculations have bee” done st FNAL energy ( Js = 2. TeV). Emphasis is placed on design issues, snalysia techniques and related software rather than physics potentials. I. INTRODUCTION : DESIGN SPECIFICATIONS. The Silicon Vertex Detector (SVX) IS one of the most critical elements of a Collider Detector dedicated to bottom Physics I. The SVX identifies the tracks belonging to B decays via reconstruction of secondary vertices.“. The decay length e+ of B mesons is about 360 pm, to be compared with the 5 to 10 pm intrinsic resolution achievable with a 25 pm pitch strip detector. Although we will describe in detail the effective resolution of such a detector through a complete Monte-Carlo simulation, it is worthwhile to first establish some elementary design rules based on a simple ha&. -

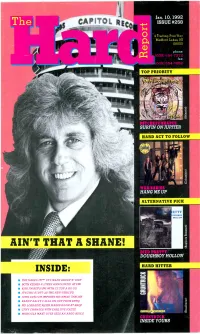

Ain't That a Shane!

Jan. 10, 1992 CAPITOL R ISSUE #258 0 4 Trading Post Way fai Medford Lakes, NJ 08055 phone: (609) 654-7272 fax: (ROMPR4-6852 TOP PRIORITY HARD ACT TO FOLLOW ALTERNATIVE PICK ',ETTY OUGHBOY 1101.1.0W AIN'T THAT A SHANE! INSIDE: HARD HITTER II THE NAKED CIT7' UTZ MADE GROUP W VEEP III BOTH KEINER & ..YKES ANNOUNCED AT EMI KISS FM RETURNS WITH ZZ TOP A GC GO IT'S ERIC STOTT AS THE NEW WXRC FD JOHN DUNTi-LN DEPARTS HIS WMAD THRONE IN RANDY RALEI. F )LLS ON OUT FROM KFMQ MD LORRAINE MCIER MAKES ROOM AT KRQF CFNY CHANGES KITH EARL JIVE JOLTED MISSOULA MA Kr OVER SEES AN ARGO ADIC S 0.111M11,1111 INSIDE YOURS NAG MANAGEMENT: ARTISTSHORIZON SERVICES ENTERTAINMENT CORP. Hard Hundred Lw Tw Artist Track LwTw Artist Track 1 1 U2 "Mysterious Ways" 32 51 Ozzy Osbourne "No More Tears" 2 2VAN HALEN "Right Now" 26 52The Who "Saturda Ni ht's ..." 4 3JOHN MELLENCAMP "Love And ..." >> D 53UGLY KID JOE "Everything About ..." 6 4BRYAN ADAMS "There Will Never ..." 62 54 U2 "Who's Gonna Ride..." 20 5GENESIS "I Can't Dance" 83 55 DIRE STRAITS "The Bug" 8 6NIRVANA "Smells Like Teen ..." >> D56 RTZ "Until Your Love ..." 18 7TOM PETTY "Kings Highway" 40 57 Lynyrd Skyrd "All I Can Do ..." 9 8 GUNS N' ROSES "November Rain" 63 58 GENESIS - "Jesus He Knows..." 12 9EDDIE MONEY "She Takes My ..." 66 59JAMES REYNE "Some People" 13 10BOB SEGER "Take A Chance" 69 60 DRAMARAMA "Haven't Got A ..." 10 11 METALLICA "The Unforgiven" 72 61 VINNIE MOORE "Meltdown" 3 12 Stevie Ray Vaughan "The Sky Is. -

BROADSIDE Tinue Is That It ~ S Part of His Conspiracy to Take Over the U.S

ide #: 66 THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JANUARY 1966 PRICE -- 50¢ I N THIS ISSUE o ******* J u I ius Le s te r's ~tagolee ·HIS LIFE & SfORY (As Told By Himself) ******* ALSO SONGS BY Ed Carl Phil Ochs Johnny Cash Len Chandler OTHERS Songs About: THE STRIKE IN THE GRAPES, ALICE HERZ, SANTO DOMINGO, Etc. Talking Blues, Letters, Record Reviews, Articles ROCKY AND THE COMMUNISTS ******* -- 2 -- r I God~s Children Free Words & Music by JOHNNY CASH Copyright 1965 by (As recorded on his recent LP SOUTHWIND SONGS "Orange Blossom Special) l' ,~t j £ t:£;J J (£ J j J ¥ J \J)W J Aj 1 J ! J. it I. I'd sing more a-bout more of this land, But all God's children ain't free; ~ iJ,dUH f I'i') f'tH ~ I J J @r J J 11 he out his hand to me, All God's children ain't free. I'd sing along to a silly song I I d be happy walkin i in the street But all God's children ain't free But all God's children ain't free lim gonna sing a blues for the lid have a smile for all I meet man they done wrong But all God's children ain't free Cause all God I s children ain I t free lid whistle down the road but I Mister, how about the man wouldn't feel right you condemned to die I'd hear somebody cryin' out at By takin I everything that he I s night livin' by From a share-cropper's shack And reject him from society or penitentiary All God I s children ain't free,N o! All God I s children ain I t free Reject him from society A share-cropper's shack All God's children ain't free.