The New Wave in the Psychoanalytic Tradition Proof “Sometimes Misfortune Brings Opportunity.” Draft —Jocelyn Murray (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

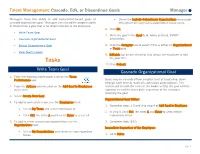

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Sacred Psychoanalysis” – an Interpretation Of

“SACRED PSYCHOANALYSIS” – AN INTERPRETATION OF THE EMERGENCE AND ENGAGEMENT OF RELIGION AND SPIRITUALITY IN CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOANALYSIS by JAMES ALISTAIR ROSS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham July 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT From the 1970s the emergence of religion and spirituality in psychoanalysis is a unique development, given its traditional pathologizing stance. This research examines how and why ‘sacred psychoanalysis’ came about and whether this represents a new analytic movement with definable features or a diffuse phenomena within psychoanalysis that parallels developments elsewhere. After identifying the research context, a discussion of definitions and qualitative reflexive methodology follows. An account of religious and spiritual engagement in psychoanalysis in the UK and the USA provides a narrative of key people and texts, with a focus on the theoretical foundations established by Winnicott and Bion. This leads to a detailed examination of the literary narratives of religious and spiritual engagement understood from: Christian; Natural; Maternal; Jewish; Buddhist; Hindu; Muslim; Mystical; and Intersubjective perspectives, synthesized into an interpretative framework of sacred psychoanalysis. -

Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life

5 PERSONAL GOALS, LIFE MEANING, AND VIRTUE: WELLSPRINGS OF A POSITIVE LIFE ROBERT A. EMMONS Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without effort. Then he feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his weakness, his emptiness. (Pascal, The Pensees, 1660/1950, p. 57). As far as we know humans are the only meaning-seeking species on the planet. Meaning-making is an activity that is distinctly human, a function of how the human brain is organized. The many ways in which humans conceptualize, create, and search for meaning has become a recent focus of behavioral science research on quality of life and subjective well-being. This chapter will review the recent literature on meaning-making in the context of personal goals and life purpose. My intention will be to document how meaningful living, expressed as the pursuit of personally significant goals, contributes to positive experience and to a positive life. THE CENTRALITY OF GOALS IN HUMAN FUNCTIONING Since the mid-1980s, considerable progress has been made in under- standing how goals contribute to long-term levels of well-being. Goals have been identified as key integrative and analytic units in the study of human Preparation of this chapter was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. I would like to express my gratitude to Corey Lee Keyes and Jon Haidt for the helpful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. 105 motivation (see Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Karoly, 1999, for reviews). The driving concern has been to understand how personal goals are related to long-term levels of happiness and life satisfaction and how ultimately to use this knowledge in a way that might optimize human well- being. -

Projective Identification As a Form of Communication in the Therapeutic Relationship: a Case Study

PROJECTIVE IDENTIFICATION AS A FORM OF COMMUNICATION IN THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP: A CASE STUDY. MICHELLE CRAWFORD UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE 1996 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Masters of Arts in Clinical Psychology http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEN1ENTS ABSTRACT 11 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER TWO THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP 6 2.1 Introduction 6 2.2 Donald Winnicott's concept of the "holding environment" as a metaphor for aspects of the therapeutic relationship 7 2.3 Wilfred Bion's concept of the "container and contained" as a metaphor for the therapeutic relationship 8 2.4 Transference 9 2.4. l Freud's Formulation: 9 2.4.2 Subsequent historical developments and debates around transference and its interpretation: 12 2.5 Countertransference 21 2.5.1 Freud's Formulation: 21 2.5.2 Subsequent historical developments and debates around countertransference and its usefulness: 22 2.6 Review 28 CHAPTER THREE PROJECTIVE IDENTIFICATION 30 3.1 Introduction 30 3.2 Freud's Contribution 30 3.3 Melanie Klein's definition of Projective Identification 32 3.4 Subsequent theoretical and technical developments of Projective Identification 35 3.5 Review 42 http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ CHAPTER FOUR CHILD PSYCHOTHERAPY 44 4.1 Introduction 44 4.2 Freud's contribution to child psychotherapy 45 4.3 Melanie Klein's play technique 48 4.4 Anna Freud's approach to child psychotherapy 52 4.5 Donald Winnicott's formulations around play and child psychotherapy 54 4.6 Review 55 CHAPTER FIVE MEI'HODOLOGY -

A Descriptive Study of Erikson's Psychosocial

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 5-2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES Anastasiya Samsanovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Samsanovich, Anastasiya, "THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1230. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1230 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Work by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 Approved by: Joseph Rigaud, Faculty Supervisor, Social Work Armando Barragán, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2021 Anastasiya Samsanovich ABSTRACT Theories shape society and become a powerful influence on major social decisions. While society has changed over time, some theories—developed decades ago—have remained the same. Among them is the Psychosocial Development Theory developed in the early 1960s by German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. -

How Freud and Marx Legitimised Our Throwaway Society1

THE TERRIBLE TWINS – how Freud and Marx legitimised our throwaway society1 One of the difficulties facing eco-critical discourse, which is at the centre of this conference, is to make that leap – an extrapolation or Kierkegaardian necessity – from theory or literary excerpt to the field of action, that is from the passive reader, the self, the “ego”, to a sense of responsibility towards the environment, to “eco”. I propose to look at how some ideas in the thought systems of seminal thinkers like Freud and Marx were used to create in different ways, sometimes unwittingly to their originators – were they alive to peruse them – a discourse of a false self or ego, leading to the present state of individual unaccountability towards the real world, the environment, or eco. I will draw on particular expostulatory works, among the vast literature, which have been compiled in recent years on the questions which readers have interrogated and which are germane here, i.e. “Freud on Women”, edited by Elizabeth Young-Bruehl, and “Why Marx was Right” – by Terry Eagleton: both provide readings of Marx and Freud which form a background to this essay. I call Freud and Marx the terrible twins because they share broad cultural similarities and because of the huge dissemination of their works in the academy, and particularly in the wider society, where they interacted with each other, and where often problematic areas in their discourse had been simplified for rapid communication through the mass media and popular understanding. 1 This essay is based on a paper given to the Ego to Eco conference at NUI Galway in June, 2011, and has been updated to include references to scholars and academics who over the years have contributed to the questions outlined here 1 The idea of the self in Freud is entirely subjective, but supported by some empirical evidence, while in Marx the idea of the self belongs entirely to the objective, empirical discourse of scientific philosophy or epistemology. -

Short Term Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Short term Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Information for Parents and Carers annafreud.org Overview Short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy (STPP) is offered to young people who are depressed and have been troubled by quite serious worries and unhappiness for some time. In the last few years the availability of STPP has been growing in the light of research studies which have indicated how helpful it can be. Many NHS clinics now offer this treatment to depressed young people. What is said in the sessions is kept confidential between the young person and their therapist. The only exception to this arises if the therapist thinks they are at risk (from themselves or someone else) or are a risk to someone else. In such a situation there will be a discussion between therapist and young person about who else in the family or community might need to know to help in keeping things safe. How long will it last? Your son or daughter will be offered 28 sessions with their therapist, each one lasting 50 minutes. Sessions take place each week at a regular time. There are breaks for holiday periods and depending on the starting date, there are likely to be two of these holiday periods in the course of the therapy, which will last overall between 8 and 9 months. The day and time of the session is negotiated between the therapist and the young person and is arranged as far as possible to take account of the demands of school, college and/or work and family circumstances. How we help There is an opportunity at the start for the young person to decide with your support whether they feel this sort of help is what they want. -

A Study of the Application of the Concepts of Karen Horney in Leadership Development Within the National Management Association of the Boeing Company

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 A study of the application of the concepts of Karen Horney in leadership development within the National Management Association of the Boeing company Frank Z. Nunez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Nunez, Frank Z., "A study of the application of the concepts of Karen Horney in leadership development within the National Management Association of the Boeing company" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 90. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/90 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology A STUDY OF THE APPLICATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF KAREN HORNEY IN LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT WITHIN THE NATIONAL MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE BOEING COMPANY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Change by Frank V. Nunez November, 2010 Susan Nero, Ph.D.– Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by Frank V. Nunez under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Susan Nero, Ph.D., Chairperson Rogelio Martinez, Ed.D. Kent Rhodes, Ph.D. © Copyright by Frank V. Nunez (2010) All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... -

![Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6594/play-and-the-young-child-musical-implications-pub-date-88-note-23p-346594.webp)

Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 934 PS 021 454 AUTHOR Brophy, Tim TITLE Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; Developmental Psychology; Early Childhood Education; *Learning Theories; Literature Reviews; *Music Education; *Orff Method; *Piagetian Theory; *Play; *Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT After noting the near-universal presence of rhythmic response in play in all cultures, this paper looks first at the historical development of theories of play, and then examines current theories of play and their implications in the teaching of music to young children. The first section reviews 19th and early 20th century theories of play, including Schiller's surplus energy theory, Hall's recapitulation theory. Groos's instinct-practice theory, Patrick's relaxation theory, and Froebel's insights into children's play and its importance in psychological and educational development. The next section provides an overview of more recent theories of play, including Parten's model of levels of social play and Freud's and Erikson's psychoanalytic theory of play. The paper pays particular attention to the role of play in Piaget's cognitive-development theory and Piaget's stages of play development from practice play to symbolic play to games with rules. The final theorist discussed is Sutton-Smith, who proposed the existence of rational and irrational play. The next section discusses the difficulty in integrating the many differing views of play and reviews Frost's efforts in this area. The final section focuses on early childhood music education, particularly Orff Schulwerk, in which play is used as a primary tool for learning. -

Intrapsychic Perspectives on Personality

PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVES ON PERSONALITY This educational CAPPE module is part i in section III: Theories of Human Functioning and Spirituality Written by Peter L. VanKatwyk, Ph.D. Introduction Psychodynamic theory goes back more than 100 years and has been a principal influence in the early history of clinical pastoral education (CPE). It is a way of thinking about personality dynamics in interpreting and understanding both the spiritual care-provider and care-receiver. This module will briefly summarize the basic theory and punctuate psychodynamic concepts that have been significant in the study of psychology of religion and theological reflection in the practice of spiritual care and counselling. Psychodynamic theories presently practiced include in historical sequence the following three schools that will be covered in this module: 1. Ego Psychology, following and extending the classic psychoanalytic theory of Freud, with major representatives in Anna Freud, Heinz Hartmann and Erik Erikson. 2. Object Relations Theory, derived from the work of Melanie Klein and members of the “British School,” including those who are prominent in religious studies and the practice of spiritual care: Ronald Fairbairn, Harry Guntrip, and D.W. Winnicott. 3. Self Psychology, modifying psychoanalytic theory with an interpersonal relations focus, originating in Heinz Kohut, systematized and applied for social work and counselling practice by Miriam Elson. In conjunction these psychodynamic theories offer three main perspectives on personality: 1. the human mind harbors conflict – with powerful unconscious forces that are continually thwarted in expressing themselves by a broad range of counteracting psychological processes and defense mechanisms. 2. each person carries an unconscious internalized world of personal relationships – with mental representations that reflect earlier experiences of self and others which often surface as patterns in current relationships and interpersonal problems. -

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D. Krista McGlynn, Breanna Wilhelmi, Heritage Clinic, a division of the Center for Aging Resources [email protected] 1 Helping Clients develop Meaning • Meaningful roles in family & the community • Meaningful activities in the community and/or individually at home • Meaning as an attitude • Meaning & Hope intertwined 2 Later life’s losses can make it harder to find meaning: • Can make it harder (physically & mentally) to follow past meaningful pursuits • Can make it harder to develop new meaningful activities/roles • Can make it harder to find hope 3 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help older clients build meaning and hope when faced with loss or decline? 4 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help clients improve their mental health and quality of life through development of altered perspectives, existential meaning, wisdom, integrity, spirituality? 5 Viktor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning 6 Existential Meaning • Victor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning: – Creating a work or doing a deed; – Experiencing something or encountering someone; – Attitudes: “Even if we are helpless victims of a hopeless situation, facing a fate that cannot be changed, we may rise above ourselves, grow beyond ourselves and by so doing change ourselves.” 7 Existential Meaning in the face of loss Developing meaning is one approach which may help. 8 Meaning • Robert Neimeyer counsels helping bereaved clients develop and internalize sense of attachment security with newly constructed meaning. • Martin Horrowitz recommends following trauma, helping clients create new meaning in a world which allows/permits such trauma to occur. -

Critical Models Interventions and Catchwords Theodor W. Adorno

EuRoPEAN PERSPECTIVES A Series in Social Thought and Cultural Criticism Lawrence D. Kritzman, Editor Critical Models Interventions and Catchwords European Perspectives presents English translations of books by leading European thinkers. With both classic and outstanding contemporary works, the series aims to shape the major intellectual controversies of our day and to facilitate the tasks of his torical understanding. Julia Kristeva Strangers to Ourselves Theodor W. Adorno Notes to Literature, vols.1 and 2 Richard Wolin, editor The Heidegger Controversy Antonio Gramsci Prison Notebooks, vols. 1 and 2 Jacques LeGoff History and Memory Alain Finkielkraut Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes Against Humanity Julia Krist eva Nations Without Nationalism Pierre Bourdieu The Field of Cultural Production Theodor W. Adorno Pierre Vidal-Naquet Assassins of Memory: Essays on the Denial of the Holocaust Translated and with a Preface Hugo Ball Critique of the German Intelligentsia by Henry W Pickford Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari What Is Philosophy? Karl Heinz Bohrer Suddenness: On the Moment of Aesthetic Appearance Alain Finkielkraut The Defeat of the Mind Julia Krist eva New Maladies of the Soul Elisabeth Badinter XY: On Masculine Identity Karl Lowith Martin Heidegger and European Nihilism Gilles Deleuze Negotiations, 1972-1990 Pierre Vidal-Naquet The jews: History, Memory, and the Present Norbert Elias The Germans Louis Althusser Writings on Psychoanalysis: Freud and Lacan Elisabeth Roudinesco jacques Lacan: His Life and Work Ross Guberman julia Kristeva Interviews Kelly Oliver The Portable Kristeva Pierra Nora Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past, vol. 1: Conflicts and Divisions, vol. 2: Traditions, vol.