430 Pm Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside.Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS?You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain‟t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and Johnny -

Renvoi Relatif À La Loi Sur La Cour Suprême, Art. 5 Et 6, DATE : 20140321 2014 CSC 21 DOSSIER : 35586

COUR SUPRÊME DU CANADA RÉFÉRENCE : Renvoi relatif à la Loi sur la Cour suprême, art. 5 et 6, DATE : 20140321 2014 CSC 21 DOSSIER : 35586 Dans l’affaire d’un renvoi par le Gouverneur en conseil concernant les articles 5 et 6 de la Loi sur la Cour suprême, L.R.C. 1985, ch. S-26, dans le décret C.P. 2013-1105 en date du 22 octobre 2013 TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE OFFICIELLE CORAM : La juge en chef McLachlin et les juges LeBel, Abella, Cromwell, Moldaver, Karakatsanis et Wagner MOTIFS CONJOINTS : La juge en chef McLachlin et les juges LeBel, Abella, (par. 1 à 107) Cromwell, Karakatsanis et Wagner MOTIFS DISSIDENTS : Le juge Moldaver (par. 108 à 154) NOTE : Ce document fera l’objet de retouches de forme avant la parution de sa version définitive dans le Recueil des arrêts de la Cour suprême du Canada. RENVOI RELATIF À LA LOI SUR LA COUR SUPRÊME, ART. 5 ET 6 DANS L’AFFAIRE DU renvoi par le Gouverneur en conseil concernant les articles 5 et 6 de la Loi sur la Cour suprême, L.R.C. 1985, ch. S-26, institué aux termes du décret C.P. 2013-1105 en date du 22 octobre 2013 Répertorié : Renvoi relatif à la Loi sur la Cour suprême, art. 5 et 6 2014 CSC 21 No du greffe : 35586. 2014 : 15 janvier; 2014 : 21 mars. Présents : La juge en chef McLachlin et les juges LeBel, Abella, Cromwell, Moldaver, Karakatsanis et Wagner. RENVOI PAR LE GOUVERNEUR EN CONSEIL Tribunaux — Cour suprême du Canada — Juges — Conditions d’admissibilité à une nomination à la Cour suprême du Canada — Exigence que trois juges soient nommés parmi les juges de la Cour d’appel ou de la Cour supérieure de la province de Québec ou parmi les avocats inscrits pendant au moins 10 ans au Barreau du Québec — Un juge de la Cour d’appel fédérale qui a été autrefois inscrit au Barreau du Québec pendant plus de 10 ans est-il admissible à une nomination à la Cour suprême du Canada? — Loi sur la Cour suprême, L.R.C. -

Mémoire Des Intervenants Robert Décary Et

Dossier no 35586 COUR SUPRÊME DU CANADA DANS L’AFFAIRE DU RENVOI RELATIF À LA NOMINATION DES JUGES À LA COUR SUPRÊME ENTRE LE PROCUREUR GÉNÉRAL DU CANADA APPELANT ET LES PROCUREURS GÉNÉRAUX DU QUÉBEC ET DE L’ONTARIO ROCCO GALATI CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS CENTRE INC. LES HONORABLES ROBERT DÉCARY, ALICE DESJARDINS ET GILLES LÉTOURNEAU ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE DES JUGES DE COURS PROVINCIALES INTERVENANTS Mémoire des intervenants Robert Décary, Alice Desjardins et Gilles Létourneau (Règles de la Cour suprême, articles 37, 42 et 46(12)) SÉBASTIEN GRAMMOND, AD.E. (avec la collaboration de Me Jeffrey Haylock, de Me Wesley Novotny et de Me Nicolas M. Rouleau) 57, rue Louis-Pasteur, bur. 203 Ottawa (Ontario) K1N 6N5 (613) 562-5902 (téléphone) (613) 562-5121 (télécopieur) [email protected] Procureur des intervenants Robert Décary, Alice Desjardins et Gilles Létourneau Henri A. Lafortune Inc. 2005, rue Limoges Tél. : 450 442-4080 Longueuil (Québec) J4G 1C4 Téléc. : 450 442-2040 www.halafortune.ca [email protected] S-3726-13 - 2 - PROCUREUR GÉNÉRAL DU CANADA PROCUREUR GENERAL DU CANADA (Mes René LeBlanc et Christine Mohr) (Me Christopher Rupar) 284, rue Wellington, bureau SAT-6050 50, rue O’Connor, Suite 50, bur. 557 Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0H8 Ottawa (Ontario) K1P 6L2 (613) 957-4657 (téléphone) Téléphone : (613) 670-6290 (613) 952-6006 (télécopieur) Télécopieur : (613) 954-1920 [email protected] Courriel : [email protected] Procureurs de l’appelant Correspondant de l’appelant BERNARD, ROY & ASSOCIÉS NOËL & ASSOCIÉS (Me André Fauteux) (Me Pierre Landry) 8.00 – 1, rue Notre Dame Est 111, rue Champlain Montréal (Québec) H2Y 1B6 Gatineau (Québec) J8X 3R1 (514) 393-2336 poste : 51492 (téléphone) (819) 771-7393 (téléphone) (514) 873-7074 (télécopieur) (819) 771-5397 (télécopieur) [email protected] [email protected] Procureurs du Procureur général du Québec Correspondants du Procureur général du Québec PROCUREUR GÉNÉRAL DE L’ONTARIO BURKE-ROBERTSON (Me Joshua Hunter) (Me Robert E. -

Supreme Court of Canada Cour Suprême Du Canada

SUPREME COURT OF COUR SUPRÊME DU CANADA CANADA BULLETIN OF BULLETIN DES PROCEEDINGS PROCÉDURES This Bulletin is published at the direction of the Ce Bulletin, publié sous l'autorité du registraire, Registrar and is for general information only. It ne vise qu'à fournir des renseignements is not to be used as evidence of its content, d'ordre général. Il ne peut servir de preuve de which, if required, should be proved by son contenu. Celle-ci s'établit par un certificat Certificate of the Registrar under the Seal of the du registraire donné sous le sceau de la Cour. Court. While every effort is made to ensure Rien n'est négligé pour assurer l'exactitude du accuracy, no responsibility is assumed for errors contenu, mais la Cour décline toute or omissions. responsabilité pour les erreurs ou omissions. During Court sessions the Bulletin is usually Le Bulletin paraît en principe toutes les issued weekly. semaines pendant les sessions de la Cour. Where a judgment has been rendered, requests Quand un arrêt est rendu, on peut se procurer for copies should be made to the Registrar, with les motifs de jugement en adressant sa a remittance of $15 for each set of reasons. All demande au registraire, accompagnée de 15 $ remittances should be made payable to the par exemplaire. Le paiement doit être fait à Receiver General for Canada. l'ordre du Receveur général du Canada. Consult the Supreme Court of Canada website Pour de plus amples informations, consulter le at www.scc-csc.ca for more information. site Web de la Cour suprême du Canada à l’adresse -

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain’t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and -

Jukebox Decades

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS Rock Jukebox D1 Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey 01 The Final Countdown Europe 02 More Than A Feeling Boston 02 Bat Out Of Hell Meat Loaf 03 Eye Of The Tiger Survivor 03 Breaking The Law Judas Priest 04 (Don’t Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult 04 Danger Zone Kenny Loggins 05 Piece Of My Heart Big Brother 05 Message In A Bottle Gillian 06 Walk On The Wild Side Lou Reed 06 Poison Alice Cooper 07 All The Young Dudes Mott The Hoople 07 Mighty Wings Cheap Trick 08 God Gave Rock & Roll To You Argent 08 Take It On The Run REO Speedwagon 09 Dogs Of War Saxon 09 Beginning Of The End Status Quo 10 Because The Night Patti Smith 10 The Battle Rages On Deep Purple 11 Leave A Light On Belinda Carlisle 11 Burnin’ For You Blue Oyster Cult 12 Walk This Way RUN – DMC & Aerosmith 12 You’re The Voice John Farnham 13 Broken Wings Mr Mister 13 Kyrie Mr Mister 14 Summer In The City The Lovin’ Spoonful 14 Hold On Baby J J Cale 15 Africa Toto 15 Rock ‘N Me The Steve Miller Band 16 Making Love Out Of Nothing At Air Supply 16 Call On Me Captain Beefheart All 17 Dust In The Wind Kansas 17 No Time The Guess Who 18 Fantasy Aldo Nova 18 Jessie’s Girl Rick Springfield 19 Soul Sacrifice Santana 19 Johnny B Goode Johnny Winter 20 Albatross Fleetwood Mac 20 I Think I Love You Too Much Jeff Healey Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Black Magic Woman Fleetwood Mac 01 King Of Dreams Deep Purple 02 Little Wing Stevie Ray Vaughan 02 Rock The Night Europe 03 She’s Not There Santana 03 Wasted In America Love/Hate 04 Turtle Blues Big Brother 04 Search & Destroy Iggy & The Stooges 05 Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers Jeff Beck 05 Living After Midnight Judas Priest 06 Nantucket Sleighride Mountain 06 Solid Ball Of Rock Saxon 07 Eight Miles High Byrds 07 Black Betty Ram Jam 08 American Woman The Guess Who 08 You Took The Words Right Out. -

Real Chart 1976

REAL CHART 1976 COMPILED BY THE COMPILERS AND Graham Appleyard The Real Chart 4 January 1976 & 28/12/75 1 139 139 4 1 Sailor Glass Of Champagne 2 - 109 109 new 1 2 ABBA Mamma Mia 3 80 80 1 1 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody 4 80 80 15 4 Mike Oldfield In Dulce Jubilo / On Horseback 5 80 31 5 Small Faces Itchycoo Park 6 80 2 2 Greg Lake I Believe In Father Christmas 7 80 29 7 Billy Howard King Of The Cops 8 80 6 Laurel And Hardy With The Avalon Boys The Trail Of The Lonesome Pine 9 80 9 Band Of The Black Watch Dance Of The Cuckoos 10 80 5 Andy Fairweather Low Wide Eyed And Legless 11 80 12 The Goodies Make A Daft Noise For Christmas 12 80 10 Demis Roussos Happy To Be On An Island In The Sun 13 80 16 Chris Hill Renta Santa 14 80 3 3 Dana It's Gonna Be A Cold Cold Christmas 15 80 7 The Drifters Can I Take You Home Little Girl 16 80 80 8 1 Hot Chocolate You Sexy Thing 17 - 60 60 new 1 17 Slik Forever And Ever 18 50 50 17 David Bowie Golden Years 19 50 18 Sensational Alex Harvey Band Gamblin' Bar Room Blues 20 50 25 Barry White Let The Music Play 21 50 11 Mud Show Me You're A Woman 22 50 48 3 22 Paul Davidson Midnight Rider 23 50 20 Chubby Checker Let's Twist Again / The Twist 24 50 19 10cc Art For Art's Sake 25 50 24 Fatback Band Do The Bus Stop 26 50 21 1 Bay City Rollers Money Honey 27 50 13 Stylistics Na Na Is The Saddest Word 28 50 27 Steeleye Span All Around My Hat 29 50 28 David Essex If I Could 30 - 50 new 1 30 Glyder Pick Up And Go 31 50 30 John Lennon Imagine 32 50 43 32 Ethna Campbell The Old Rugged Cross 33 50 53 33 Roxy Music Both Ends -

Rapport Annuel 2005-2006 Notre Mission

NOTRE APPUI, VOTRE RAYONNEMENT . RAPPORT ANNUEL 2005-2006 NOTRE MISSION PROMOUVOIR LA PROTECTION DU PUBLIC, PAR DES ACTIVITÉS D’INFORMATION ET DE SENSIBILISATION ET PAR UNE PARTICIPATION ACTIVE À L’ADMINISTRATION DE LA JUSTICE. IMPORTATION D’UNE VIEILLE TRADITION... L’histoire veut que l’expression « bâtonnier » provienne d’une coutume à l’effet que l’avocat considéré comme le plus digne par ses confrères porte le bâton au cours des cérémonies. Inspiré par cette histoire, le bâtonnier David R. Collier a décidé de l’importer et de remettre à son successeur le bâton ci-contre, espérant ainsi créer une nouvelle tradition au Barreau de Montréal. Le bâtonnier remercie monsieur Luc Paquette, antiquaire, pour son aide précieuse dans la conception et confection du bâton. TABLE DES MATIÈRES LE CONSEIL 4 Infractions 19 Les membres du Conseil 4 Journée du Barreau 19 Le rapport du bâtonnier 5 Liaison avec la Commission des relations du travail 20 Les réunions du Conseil du Barreau de Montréal 8 Liaison avec la Cour canadienne de l’impôt 20 Les réunions du Conseil général du Barreau du Québec 8 Liaison avec la Cour d’appel 21 Les subventions octroyées par le Conseil 8 Liaison avec la Cour d’appel fédérale et la Cour fédérale 22 Les résolutions adoptées par le Conseil 9 Liaison avec la Cour du Québec, chambre civile 23 Liaison avec la Cour du Québec, chambre de la jeunesse 24 L’ADMINISTRATION 10 Liaison avec la Cour municipale de Montréal 25 Le rapport de la directrice générale 10 Liaison avec la Cour supérieure, chambre commerciale 26 Les ressources -

Pearl, an English Poem of the Xivth Century

\jf\>C^(r^ r^M\ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Coolidge Otis Chapman ,PhD. Cornell, 1927 URIS . CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRAfiY 924 059 407 035 DATE DUE i^Avi OBp PRINTED IN U.S-A. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924059407035 SELECT EARLY ENGLISH POEMS * SELECT EARLY ENGLISH POEMS EDITED BY SIR I. GOLLANCZ. VIII. PEARL, WITH MODERN RENDERING, &c. :'Q^;gf;;'0';.ig):;-.(S;::0"-V0L>;.©}l -'••' •^4. ' • 'ii'iimi'r'n By arrangement with Messrs. Chatto &^ IVindus, the publishers of " The Medieval Library" in which the Ordinary Edition is included, this Large Paper Edition {limited to 200 copies, 1^0 for sale) has been specially, prepared, to range in format with the " Series of Select Early English Poems" of which it forms Vohcme VIII. J^hlfn^yt ^.^jJi/ OAt PEARL AN ENGLISH POEM OF THE XIVI!? CENTURY: EDITED, WITH MODERN RENDERING, TOGETHER WITH BOCCACCIO'S OLYMPIA, BY SIR ISRAEL GOLLANCZ, Litt.D., F.B.A. HUMPHREY MILFORD : OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN CORNER: LONDON 1921 URiS LIBRARY lltM 9 k 1QQ1 ''^' vA^ ^^^ All rights reseri>ed WE LOST YOU—FOR HOW LONG A TIME- TRUE PEARL OF OUR POETIC PRIME ! WE FOUND YOU, AND YOU GLEAM RE-SET IN BRITAIN'S LYRIC CORONET. TENNYSON CONTENTS PREFATORY NOTE My edition of 'Pearl' in 1891 was my first contribution to Middle English studies, and my interest in the poem has remained unabated all these years, during which I have endeavoured to understand it aright and to unravel many a problem. -

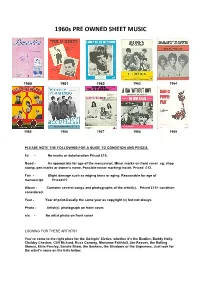

1960S PRE OWNED SHEET MUSIC

1960s PRE OWNED SHEET MUSIC 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES. Ex - No marks or deterioration.Priced £15. Good - As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Minor marks on front cover eg. shop stamp, pen marks or owner's name. Possible minor marking inside. Priced £12. Fair - Slight damage such as edging tears or aging. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album - Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year - Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo - Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a - No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for the Swingin’ Sixties, whether it’s the Beatles, Buddy Holly, Chubby Checker, Cliff Richard, Russ Conway, Marianne Faithfull, Jim Reeves, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, Sandie Shaw, the Seekers, the Shadows or the Supremes. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. Title Writer and Composer condition Photo Year 19th Nervous Mick Jagger/Keith Richard ex The Rolling Stones 1966 breakdown 59th Street Paul Simon ex Harpers Bizarre or 1967 bridge song Paul Simon (Feelin‟ groovy) A Banda Chico Buarque de Hollanda fair Herb Alpert 1966 Acapulco Greenslade/Allan good Kenny Ball 1962 1922 Acapulco Eldon Allan/Shel Talmy good Kathy Kirby/Johnny B. 1962 1922 (vocal Great version) A clown am I Winifred Atwell ex Johnny Hackett 1967 Adios, Ralph Freed/Jerry Livingston ex Jim Reeves 1962 amigo -

SUPREME COURT of CANADA CITATION: Reference Re Supreme

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6, 2014 DATE: 20140321 SCC 21 DOCKET: 35586 In the Matter of a Reference by the Governor in Council concerning sections 5 and 6 of the Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26, as set out in Order in Council P.C. 2013-1105 dated October 22, 2013 CORAM: McLachlin C.J. and LeBel, Abella, Cromwell, Moldaver, Karakatsanis and Wagner JJ. JOINT REASONS: McLachlin C.J. and LeBel, Abella, Cromwell, Karakatsanis (paras. 1 to 107): and Wagner JJ. DISSENTING REASONS: Moldaver J. (paras. 108 to 154) NOTE: This document is subject to editorial revision before its reproduction in final form in the Canada Supreme Court Reports. REFERENCE RE SUPREME COURT ACT, SS. 5 AND 6 IN THE MATTER OF a Reference by the Governor in Council concerning sections 5 and 6 of the Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26, as set out in Order in Council P.C. 2013-1105 dated October 22, 2013 Indexed as: Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6 2014 SCC 21 File No.: 35586. 2014: January 15; 2014: March 21. Present: McLachlin C.J. and LeBel, Abella, Cromwell, Moldaver, Karakatsanis and Wagner JJ. REFERENCE BY GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL Courts — Supreme Court of Canada — Judges — Eligibility requirements for appointment to Supreme Court of Canada — Requirement that three judges be appointed to Court from among judges of Court of Appeal or of Superior Court of Quebec or from among advocates of at least 10 years standing at Barreau du Québec — Whether Federal Court of Appeal judge formerly member of Barreau du Québec for more than 10 years eligible for appointment to Supreme Court of Canada — Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. -

Marvin Gaye the Complete Guide

Marvin Gaye The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 01 Apr 2012 19:02:19 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Marvin Gaye 1 Discography 18 Marvin Gaye discography 18 Studio albums 25 The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye 25 That Stubborn Kinda Fellow 27 When I'm Alone I Cry 28 Hello Broadway 30 How Sweet It Is to Be Loved by You 31 A Tribute to the Great Nat "King" Cole 32 Moods of Marvin Gaye 34 I Heard It Through the Grapevine 36 M.P.G. 38 That's the Way Love Is 40 What's Going On 42 Let's Get It On 51 I Want You 62 Here, My Dear 71 In Our Lifetime 76 Midnight Love 81 Dream of a Lifetime 85 Romantically Yours 88 Vulnerable 89 Soundtrack albums 92 Trouble Man 92 Duet albums 95 Together 95 Take Two 97 United 98 You're All I Need 100 Easy 103 Diana & Marvin 105 Live albums 110 Marvin Gaye Recorded Live on Stage 110 Marvin Gaye Live! 111 Live at the London Palladium 113 Marvin Gaye at the Copa 118 Compilation albums 120 Greatest Hits 120 Greatest Hits, Vol. 2 122 Marvin Gaye and His Girls 123 Super Hits 125 Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell's Greatest Hits 126 Marvin Gaye's Greatest Hits 127 Motown Remembers Marvin Gaye: Never Before Released Masters 128 The Marvin Gaye Collection 129 The Norman Whitfield Sessions 132 The Very Best of Marvin Gaye 133 The Master 136 Anthology: Marvin Gaye 139 Marvin Gaye: The Love Songs 142 The Complete Duets 143 Associated albums 146 Irresistible 146 The Essential Collection 148 Tribute albums 150 Inner City Blues: The Music of Marvin Gaye 150 Tribute songs 151 "Missing You" 151 "Nightshift" 153 Singles 155 "Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide" 155 "Mr.