1 #Noborders. Världens Band: Creating and Performing Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

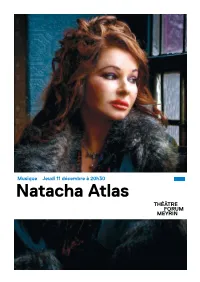

Natacha Atlas

Musique Jeudi 11 décembre à 20h30 Natacha Atlas BaseGVA basedesign.com BaseGVA Photo © Banjee Théâtre Forum Meyrin, Place des Cinq-Continents 1, 1217 Meyrin / +41 22 989 34 34 / forum-meyrin.ch Service culturel Migros, rue du Prince 7, Genève, +41 22 319 61 11 / Stand Info Balexert, Migros Nyon-La Combe Jeudi 11 décembre à 20h30 Natacha Atlas Le concert On dit d’elle qu’elle est la rose raï du Caire. Une Dalida qui aurait emprunté le chemin inverse, l’emmenant des faubourgs de Bruxelles au relatif anonymat de la capitale égyptienne. Natacha Atlas est surtout, depuis une vingtaine d’années, l’incarnation de ce que la world music peut offrir de mieux sur scène, mélangeant des racines orientales, faites de danses du ventre et de youyous hululés, à des rythmes électroniques plus européens, souvenirs de son passage, au début des années 1990, dans le groupe Transglobal Underground. Depuis toujours, elle aime faire le grand écart, construire un pont entre deux rives qu’elle seule semble à même de réunir. Pour sa nouvelle tournée, cette crooneuse des sables s’est entourée d’un aréopage de musiciens issus tout autant du jazz que du folklore arabe. Le résultat est toujours aussi envoûtant, qu’elle entonne le remarquable Rise to Freedom, en hommage à la révolution du Nil de 2011, ou reprenne le joyau qu’est River Man, un titre du compositeur anglais Nick Drake. Natacha Atlas n’aime pas les barrières, encore moins les interdits. Femme du monde, héritière des grandes voix moyen-orientales, on pense à Oum Kalsoum ou à la diva libanaise Fairouz, elle est capable de nous émerveiller avec un concert digne des mille et une nuits étoilées. -

Diasporic Music in a Time of War”: Pantomime Terrors

“Diasporic Music in a Time of War”: Pantomime Terrors John Hutnyk1 Centre for Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London I increasingly find it problematic to write analytically about “diaspora and music” at a time of war. It seems inconsequential; the culture industry is not much more than a distraction; a fairy tale diversion to make us forget a more sinister amnesia behind the stories we tell. This paper nonetheless takes up debates about cultural expression in the field of diasporic musics in Britain. It examines instances of creative engagement with, and destabilisation of, music genres by Fun^da^mental and Asian Dub Foundation, and it takes a broadly culture critique perspective on diasporic creativity as a guide to thinking about the politics of hip- hop in a time of war. Examples from music industry and media reportage of the work of these two bands pose both political provocation and a challenge to the seemingly unruffled facade of British civil society, particularly insofar as musical work might still be relevant to struggles around race and war. Here, at a time of what conservative critics call a ‘clash of civilizations’, I examine how music and authenticity become the core parameters for a limited and largely one-sided argument that seems to side-step political context in favour of sensationalised – entrenched – identities and a mythic, perhaps unworkable, ideal of cultural harmony that praises the most asinine versions of multiculturalism while demonizing those most able to bring it about. Here the idea that musical cultures are variously authentic, possessive or coherent must be questioned when issues of death and destruction are central, but ignored. -

Fusões, Exotismos E Antirracismo Na Música Eletrônica Dançante* David Hesmondhalgh**

Tempos internacionais: fusões, exotismos e antirracismo na música eletrônica dançante* David Hesmondhalgh** Plágio, enquanto tática cultural, deve ser destinado aos pútridos capitalistas, não aos potenciais camaradas. – Hakim Bey. Resumo Este ensaio busca analisar a complexa política de tecnologia, representação e instituição na música popular. Traça a história das gravadoras independentes britânicas, particular- mente da música eletrônica dançante, com base em pesquisa realizada em Londres na dé- cada de 1990. O estudo etnográfico da companhia Nation Records é discutido à luz da com- plexa política cultural da conjuntura da década de 1990. Palavras-chave Música eletrônica dançante – século XX – autoria – indústria cultural – tecnologia – crítica cultural. Abstract This essay seeks to analyse the complex politics of technology, representation and insti- tution in popular music. It traces the history of British independent record companies, par- ticularly electronic dance music companies, based on research conducted in London in the 1990s. The ethnographic study of Nation Records is discussed in the light of the complex cultural politics of that 1990s conjuncture. Keywords Electronic dance music – 20th century – authorship – recorded music – cultural industry – cul- tural criticism. _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Virtual-Musical Other: Creating Unique Worlds Through

THE VIRTUAL-MUSICAL OTHER: CREATING UNIQUE WORLDS THROUGH MUSICAL SOUND IN VIDEOGAMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC MAY 2014 By Jeremiah Sundance French Thesis Committee: Dr. Jane Freeman Moulin, Chairperson David A.M. Goldberg Dr. Katherine McQuiston Dr. Christine Yano ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to Darren Korb and Raison Varner for sharing their experiences with me. Their openness and willingness to discuss their work with me, even through their hectic schedules, made this project both possible and extremely enjoyable. Special thanks to Varner and Gearbox Software for allowing me to visit their offices. I would also like to thank all the participants who took time out of their schedules to meet, play a game, and have a discussion. They were a wonderful group of people with which I was happy to work. Thank you to Ruben Campos, Larry Catungal, Justin Ka’upu, Chadwick Pang, Jonathan Richter, Candice Steiner, and Teri Skillman for their assistance and feedback, however large or small. Discussing ideas, receiving their edits, hearing their motivational words, and having them come through for me with small technical issues has made all the difference in the world. My work would not have been possible without their assistance. Thank you to Dr. Katherine McQuiston and David A.M. Goldberg for inspiring my research. Their knowledge helped spark my thought processes and develop my theories. I am very grateful for Dr. -

BORN, Western Music

Western Music and Its Others Western Music and Its Others Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music EDITED BY Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London All musical examples in this book are transcriptions by the authors of the individual chapters, unless otherwise stated in the chapters. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2000 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Western music and its others : difference, representation, and appropriation in music / edited by Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-520-22083-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 0-520--22084-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Music—20th century—Social aspects. I. Born, Georgina. II. Hesmondhalgh, David. ml3795.w45 2000 781.6—dc21 00-029871 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 10987654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). 8 For Clara and Theo (GB) and Rosa and Joe (DH) And in loving memory of George Mully (1925–1999) CONTENTS acknowledgments /ix Introduction: On Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music /1 I. Postcolonial Analysis and Music Studies David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 3 II. Musical Modernism, Postmodernism, and Others Georgina Born / 12 III. Othering, Hybridity, and Fusion in Transnational Popular Musics David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 21 IV. Music and the Representation/Articulation of Sociocultural Identities Georgina Born / 31 V. -

Walls Have Ears — As Glorious As Ever | Financial Times

5/11/2020 Transglobal Underground: Walls Have Ears — as glorious as ever | Financial Times Albums Transglobal Underground: Walls Have Ears — as glorious as ever With swaggering reggae beats to modern Maghrebi, the near-original line-up reunites for a new studio album Swaggering beats: Natacha Atlas and Hamid Mantu David Honigmann MAY 8 2020 Transglobal Underground were ahead of their time. Thirty years ago they rose from the ashes of the underrated indie band Furniture as a fusion of dance and world music, the furrow they have ploughed ever since. A revolving cast of characters have come and gone — the Egyptian-British singer Natacha Atlas, whose subsequent solo albums have ranged from Cairene strings to Arabic jazz; Nick Page, known in his TGU incarnation as Count Dubulah, who went on to Syriana, Xaos and most notably Dub Colossus; Johnny Kalsi of the Dhol Foundation and Imagined Village. TGU were in effect a proud net exporter of talent to the UK’s world music scene. Recently the band went from centrifugal to centripetal. Atlas and Dubulah returned to the mother ship, funds were crowdsourced, tours were held, and something approaching the original line-up came together for Walls Have Ears. The collisions are as glorious as ever. The opening track, “City In Peril”, rides in on a swaggering reggae beat with chants of “move over” and a fluent trumpet solo from Yazz Ahmed, and Tim Whelan’s flute fluttering over the top. Atlas duets with Sheema Mukherjee, the band’s sitar virtuoso, on “Ruma Jhuma”, a love song in Hindi and Arabic with gently swaying tabla. -

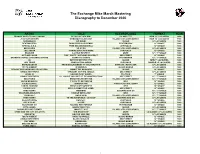

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Populární Hudba Zahraniční

Číslo Rok Autor Název Styl 3151 rok:2005 …And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead Worlds apart alterantive rock 5645 rok:2006 …And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead So divided alternative rock 3979 rok:2000 10CC /populární kapela ze 70.let/ Best of the 70's soft rock 4816 rok:1995 2 Unlimited /nejv ětší hity legendární disco formace/ Hits Unlimited disco/dance 4177 rok:1996 2Pac /fantastické dvojalbum zast řelené hip-hop hv ězdy/ All eyez on me - 2CD hip-hop 5696 rok:2005 3 Doors Down Seventeen days post-grunge 2008 rok:2002 3 Doors Down /pro fandy:Creed, Nickelback/ Away from the sun post-grunge 5483 rok:2002 30 Seconds to Mars 30 Seconds to Mars alter..rock/EMO 5637 rok:2009 30 Seconds to Mars This is war Emo/alter-prog r. 3706 rok:2007 30 Seconds to Mars /pro fandy:My Chemical Romance/ A Beautiful EMO/alter.rock 6432 rok:2013 30 Seconds to Mars Love lust faith & dreams symph/alter./rock 5676 rok:2006 36 Crazyfists Rest inside the flames EMO/hard-core 2329 rok:2004 36 Crazyfists /zní to jako:Lostprophets,SystemOfADown/ A snow capped romance EMO/nu metal 1169 rok:2001 4 Hero Creating patterns nu-jazz 3127 rok:1992 4 Non Blondes /jedna super deska s hitem What's up/ Bigger, better, faster, more! rock 5858 rok:2009 50 Cent Before i self destruct + DVD hip-hop 3162 rok:2005 50 Cent The Massacre hip-hop 4130 rok:2007 50 Cent /nové album/ Curtis hip-hop 6485 rok:2012 69 Eyes X gothic rock/metal 3930 rok:2002 69 Eyes /pro fandy:HIM,Paradise Lost/ Paris kills gothic metal 2162 rok:2000 69 Eyes /zní to jako: HIM,Type O Negative,Sisters -

Mike Marsh Discography

Mike Marsh Discography ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR 02:54 SUGAR POLYDOR / FICTION DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 1789 CA IRA MON AMOUR UNIVERSAL MERCURY FRANCE CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 0 8 0 0 1 VORAGINE WORKING PROGRESS CD ALBUM 2007 18 WHEELER THE HOURS AND THE TIMES CREATION CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 18 WHEELER YEAR ZERO CREATION CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 49ERS GOT TO BE FREE ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1992 4GOTTEN FLOOR THE FORGOTTEN FLOOR JATO MUSIC CD ALBUM 2008 808 STATE DON SOLARIS ZTT CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 808 STATE BOND ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" / 10" SINGLE 1996 808 STATE LOPEZ ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 AARON BIRDS IN THE STORM WAGRAM / CINQ 7 CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ABC GREATEST HITS PHONOGRAM CD PRE-MASTERING 1990 ADAM CLAYTON & LARRY MULLEN MISSION : IMPOSSIBLE MOTHER 7" SINGLE 1996 ADAM KESHER CHALLENGING NATURE DISQUE PRIMEUR CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ADD N TO (X) AVANT HARD MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1998 ADD N TO (X) REVENGE OF THE BLACK REGENT MUTE CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1999 ADD N TO (X) LOUD LIKE NATURE MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 2002 ADDIE BRIK LOVED HUNGRY BREAKIN' BEATS CD ALBUM 2003 ADDIE BRIK STRIKE THE TENT ADDIE BRIK CD ALBUM 2008 ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN (THOMAS GOLD REMIX) XL RECORDINGS CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 ADRENALIN JUNKIES ADRENALIN JUNKIES LA PLAGE CD ALBUM 2008 ADSTEDT DREAMING WIDE AWAKE VERATONE SWITZERLAND DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AFTERGLOW NEVER GROW OLD EP JACK McDONALD DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AGENT PROVOCATEUR RED TAPE EPIC CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1996 -

Reidentification of Artists and Genres in KDD Cup 2011

Reidentification of Artists and Genres in KDD Cup 2011 Matthew J. H. Rattigan [email protected] University of Massachusetts Amherst, 140 Governors Dr., Amherst, MA 01003 USA Abstract has exactly three genres (or “Categories”, as they are known on the Yahoo! Music site). The data for the KDD Cup 2011 competi- tion are drawn from a real-world set of pop- Under the above assumptions, we can compare the un- ular music reviews. Included in the data is labeled KDD Cup artist with real-world Yahoo! Music an “item taxonomy”, which describes the re- artists in order to find a suitable match. The band Fis- lationship between four musical item types cher Z, for example, is an unsuitable match, as their (artists, albums, tracks, and genres). To online discography only contains seven albums. An protect the data, item identifiers have been artist such as Meatloaf certainly has enough albums scrubbed and replaced by numeric placehold- (56) to be a match, but none of those albums con- ers. In this work, we show that relational tain more than 31 tracks. The entry for Elvis Presley structure is sufficient for reidentifiying many contains 109 albums, 17 of which boast 69 or more of the artists and genres in the taxonomy tracks; however, there is no consistent assignment of data set. genres that satisfies our assumptions. The band Tool, however, is compatible with Artist 197656. The Tool discography contains 19 albums containing between 0 and 69 tracks. These albums are described by exactly 1. Introduction 10 genres, which can be assigned to the unlabeled KDD The data for the KDD Cup 2011 competition are Cup genres in a consistent manner. -

The Middle East in the American Popular Music Imaginary, 1955-2014 by Meghan Drury BA in Anthropology, May 2

Sonic Affinities: The Middle East in the American Popular Music Imaginary, 1955-2014 by Meghan Drury B.A. in Anthropology, May 2004, Scripps College M.A. in Ethnomusicology, June 2006, UC Riverside A dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 15, 2016 Melani McAlister Associate Professor of American Studies and International Affairs Gayle Wald Professor of English and American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Meghan Elizabeth Drury has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 7, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Sonic Affinities: The Middle East in the American Popular Music Imaginary, 1955-2014 Meghan Drury Dissertation Research Committee: Melani McAlister, Associate Professor of American Studies and International Affairs, Dissertation Co-Director Gayle Wald, Professor of English and American Studies, Dissertation Co-Director Josh Kun, Professor of Communication and American Studies and Ethnicity, University of Southern California, Committee Member Antonio López, Associate Professor of English, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2016 by Meghan Drury. All rights reserved iii This dissertation is dedicated to my mom, my Nana, and Auntie Pussy – intelligent, resourceful women and enduring role models. iv Acknowledgments This dissertation is the product of a decade-long graduate school journey, which began in the music department at UC Riverside. I owe a debt of gratitude to Deborah Wong, René T.A. Lysloff, Jonathan Ritter, Leonora Saavedra, Byron Adams, and Griff Rollefson for their support and encouragement of my work as a master’s student. -

José María Arguedas Is My John Lennon’: Arguedas As Cultural Hero in Lima’S Independent Music Scene

Vik, A. 2018. ‘José María Arguedas is My John Lennon’: Arguedas as Cultural Hero in Lima’s Independent Music Scene. Iberoamericana – Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 47(1), 83–93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16993/iberoamericana.424 RESEARCH ARTICLE ‘José María Arguedas is My John Lennon’: Arguedas as Cultural Hero in Lima’s Independent Music Scene Alissa Vik This article discusses the way that young people in Lima establish themselves as heirs to Arguedas, specifically through the analysis of music by contemporary fusion bands Crónica de Mendigos and Tayta Bird. I argue that they use Arguedas as a signifier in their music to show their cultural capital, legiti- mize their musical projects, search for belonging as young limeños with roots in other places in Peru, and celebrate cultural diversity. These two bands—in contrast to those founded in the 1990s that have been studied in relation to Arguedas—actually include excerpts of Arguedas’ texts or sound clips of him singing in their songs. Unlike academics, however, these musicians are not trying to establish whether or not Arguedas was ‘right’, and more often dialogue with ideas about Arguedas—his notion of mestizaje as celebratory multiculturalism, his idea of an inclusive nation as one of todas las sangres, his own search for belonging as a mestizo—rather than with the texts themselves. Through establishing themselves as heirs to Arguedas and creating music which mixes autochthonous and global genres, these musicians establish themselves as cosmopolitans who ‘belong’ both in the Andes and in Lima or any other global city.